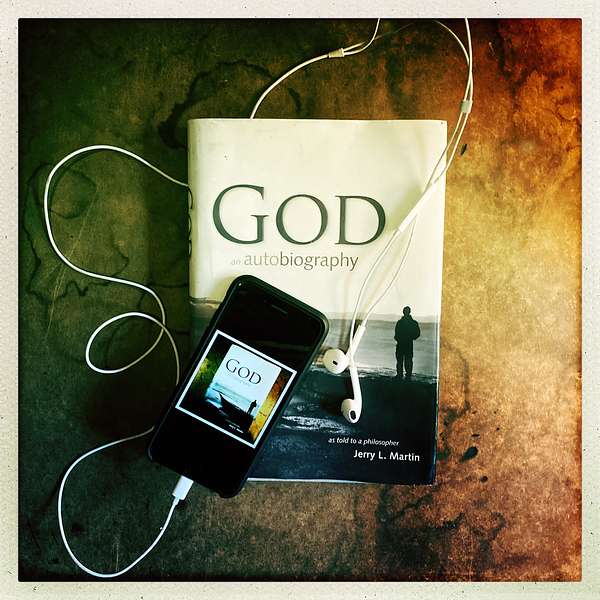

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

73. What’s On Our Mind- God's Evolution

Scott and Jerry recap the past three podcast stories, covering Where Two Philosophers Wrestle With God, and What's On Your Mind. An insightful conversation between Jerry and Scott about their personal spiritual experiences while recapping points from the most recent series, including dialogues, and responses from readers and listeners.

Listen to a philosopher's experience communicating with God, where God explains human history as co-evolving with His own dramatic story. Not a theological debate but a discussion that includes philosophical theories, often seen through the lens of logic, and spiritual experiences perceived through the lenses of different religious communities. Join us in this still-lingering time of enforced leisure and understand what it means when God said, "Listen!"

This interesting conversation covers the paradox of evil, how to pray, and whether a parent's frustrations are similar to God's frustration. But, can God be like us in just doing His best?

Read God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher.

Begin the dramatic adaptation of God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher

Related Episodes: [Two Philosophers Wrestle With God] Nature Of God And Divine Reality [Part 1][Part 2]; [What's On Your Mind] Trusting God

Share Your Story | Site | Facebook | Instagram | Twitter | YouTube

Scott Langdon [00:00:17] This is GOD: an Autobiography, the podcast, a dramatic adaptation and continuing discussion of the book God: an Autobiography, as Told to a Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin. He was a lifelong agnostic, but one day, he had an occasion to pray. To his vast surprise, God answered- in words. Being a philosopher, he had a lot of questions, and God had a lot to tell him.

Scott Langdon [00:00:58] Episode 73. Welcome to episode 73 of GOD: an Autobiography, the podcast. I'm Scott Langdon. This week we reference episodes 70, 71, and 72 as we bring you the fourth installment of our series, What's On Our Minds, where Jerry and I talk about interesting topics taken from the last three episodes of the podcast. Far from being a recap episode of what you might have missed, here, Jerry and I discuss the problem of either/or when considering God's story, why we might have trouble comprehending the idea of a developing God, and what it really means to listen. If you have a question, comment, or story of your own about an encounter with God or a spiritual experience, drop us an email to questions@godanautobiography.com. Thanks for spending this time with us. I hope you enjoy the episode.

Scott Langdon [00:02:00] Welcome back, everybody, to episode 73, this is What's On Our Minds. And Jerry, this is the fourth time we're doing this, and I really love doing this with you, talking about our experiences with things.

Jerry L. Martin [00:02:13] Yeah. And what's on my mind is always what's on everybody else's mind- what's on Oxenberg's mind and the dialogues, what's on Wayne's mind from that very interesting communication, which we'll be returning to because he told a long story, and these things are very much on my mind.

Scott Langdon [00:02:32] Yeah, yeah. And, you know, what we like to do in this episode series that we've been doing, the What's On Our Minds, as we kind of keep it focused on the last three episodes that we had. So those would be episode 70 and 71, which are parts one and two of your fourth dialogue with Dr. Richard Oxenberg. Then last week's episode, we had our fourth session of What's On Your Mind, where we go into the mailbag. We, you know, we read from folks who have written in to us, either listeners of the podcast or readers of the book, or sometimes both, and offering their stories, their experiences. And like you said, we had a great one last week from a gentleman named Wayne. It was a very lengthy email, and all three of these past episodes have brought some really interesting questions and thoughts to my mind.

Jerry L. Martin [00:03:20] Oh, good, good.

Scott Langdon [00:03:22] Well, we've talked about this before, you know, one of the many ways that God seems to be communicating to me, it's by way of working on this podcast. You know, we talked about, I feel like God communicates to me through art, whether it's what I'm making or somebody else is making. So, you know, so sometimes you are the creator, sometimes you're the audience, and you know, sometimes you're both- it's interesting. But one of the ways that God communicates to me, I have experiences with God, is working on this very project. And during the course of doing the work, I sometimes feel nudged to pay attention, to relisten to certain things. So, I listened to episode 70, and 71, and 72 for the preparation for this, for talking about this with you. And I felt nudged in episode 70 to listen to something again. And one of the things that I was drawn to was right at about the 15- between the 15 and 16-minute mark of the episode, Richard asks you, is Genesis wrong?

Jerry L. Martin [00:04:29] Right. (Laughing).

Scott Langdon [00:04:29] And now you guys are talking about the creation story in Genesis, which he reads from in the Bible, and compares it to what God gave you in terms of the revelation of, "This was what it was like for me," God says, "this is how- this was sort of my view of what was going on during creation." And it was framed as like, you know, it's either-- is it either this or is it that, right? So is the Bible right, or is this right? And you gave a wonderful answer to that, and if I can, I'd like to just play that bit of the episode where he asked you if Genesis is wrong and talks about a little bit, and then you give your wonderful answer, and we'll come back and talk about that on the other side.

Dr. Richard Oxenberg [00:05:14] Is Genesis wrong? Is, I mean, in other words, is there-- is there or is there not some truth to the way in which Genesis presents the creation story in your mind, as you would think about this? I mean, if we compare these two, are we going to say, "Well, you know, the author of Genesis just got it wrong... and this is what really happened, and this was, you know- where this story came from, we can't say." I mean, what would you say about that?

Jerry L. Martin [00:05:51] Well, that's not a question I've asked myself. I tend to be trusting with regard to revelations...

Dr. Richard Oxenberg [00:05:58] (Laughing).

Jerry L. Martin [00:05:58] ...and assume that they're each telling us something.

Dr. Richard Oxenberg [00:06:04] Right.

Jerry L. Martin [00:06:05] And I don't think one has to there-- I don't think that implies one has to hammer them into one story and ask, "Well, what exactly is the right story?" These are both rather metaphorical and majestic presentations. I mean, how is God going to communicate creation in a way that we're going to find it easy to grasp?

Scott Langdon [00:06:30] So that was a clip of episode 70, where Richard asks you in conversation, is Genesis wrong compared to what God gave you? I loved what you said to him that it's a... they can both be true, there doesn't have to be a one or the other, that there's different aspects of the story.

Jerry L. Martin [00:06:50] Yeah, that's right. Most people, even who read the Bible avidly, didn't notice, don't notice that there are two accounts of creation in Genesis. There's Genesis 1, and there's Genesis 3. And I remember growing up, a poem often used in the little school poetry contest, where you memorize a poem and recite it, was James Weldon Johnson, a Black American poet of, I guess, early 20th century or mid-20th century who draws on Genesis 3 and where God is, I can't remember the details, but God is sort of scooping up clay or something and fashioning the first person, you know, Adam out of clay and then breathing life into this clay figure, and it goes on from their very different account. And the authors of... I shouldn't say the authors, but the editor, the redactors, as the specialists call them, who put the Bible together. You had all these stories and text, and so forth. Someone had to decide what's good, what should be included, what should not be included. They included both versions. They included both. And that's a very wise decision, for one thing, for us mortals to start picking and choosing is a little difficult. It may be a little beyond our competence to decide- oh, is Genesis 1 more right, or is Genesis 3 more right, or God: an Autobiography more right?

Jerry L. Martin [00:08:19] One thing I'm now noticing, as I hadn't thought about it before, but Genesis 1 is from a third person point of view. It's saying there's a God already, you know, it's kind of taken for granted as though who knows who this speaker is? The tradition had it that Moses, but that doesn't quite make sense, that Moses were not present for creation somehow, you know? So some kind of vision had to come to somebody, but it's the third person vision. There is God separating the darkness from the light, creating the first day, and so forth. God: an Autobiography is extremely different and maybe unique in the history of revelations. I don't know. But it's a first person narrative of what it was like for God, and what it was like for God might be somewhat different from how it would look in retrospect from somebody else who has a kind of vision of the story. But for God, it's a story of being born into the world, and the world being born almost as God's body or something. You know, when I see that, I use the image in talking to Richard Oxenberg of an orchestra. Suddenly, you find you've got to conduct the orchestra. But that's a little bit off because God is also the orchestra.

Scott Langdon [00:09:46] Right.

Jerry L. Martin [00:09:46] And at the beginning, it's very much like, in fact, this image was used there also, it's as if God is sort of punching his arms and legs out, you know, in infinite space and trying to figure out- what am I? And you can, you know, it's very much like a newborn infant. What are these appendages? What do they do-- (Laughing)

Scott Langdon [00:10:08] Trying to grab on to things but didn't know-- couldn't-- try understanding the feeling of grabbing and what, what does that even mean, and grabbing on to what, at you know? Yeah--

Jerry L. Martin [00:10:19] Yes, yes. So anyway, those are some of the differences, and it behooves us to stand back a little bit with some humility and try to take it all in the way we take in very different types of great music or great literature or great philosophical systems. We try to take-- just sort of take them in and without hammering them into, you know, this is right, that's wrong, or trying to hammer them into one bigger view. Just take them in.

Scott Langdon [00:10:50] The autobiographical aspect, the first person aspect of this particular story of creation in God: an Autobiography, was really interesting to me. As I was preparing and developing the character of Jerry, which was you, for the audio adaptation of the book. So, I know we've talked about it before, how it's-- I'm playing a character because it's not me, and yet I have the benefit of talking to you. You know, this really happened to you and your experience. So it's still going to be your experience filtered through, in a sense, filtered through my delivery of your experience.

Jerry L. Martin [00:11:36] But you see it's not third person.

Scott Langdon [00:11:37] Right.

Jerry L. Martin [00:11:38] Because I'm living at first person, and you are entering Jerry Martin as character, as a first person, first person experience.

Scott Langdon [00:11:47] Right, right. And that's what's so fascinating about it. And when I think about that and how God talks about creation in this way, so it's very-- we talked about the anthropomorphism. You know, it was- you want me to get more anthropomorphic? And God is saying, "That's the language I have to use for you to understand- how else would I explain it? I have to use this kind of language." And so God is talking about in ways of His experience (God's experience) in the manner of a person. The personhood--

Jerry L. Martin [00:12:19] Yes.

Scott Langdon [00:12:19] These things, I would feel it's stretching, and so forth, right? So when I was preparing the Jerry to make Jerry real and in first person, I also had this sense, as Jerry seemed to, of the feeling that God was giving contradictory instructions or contradictory accounts of certain things to different people of different traditions, different ways of faith or however you want to talk about it, and God keeps rebuffing that. He rebuffs that often. But, you know, when Jerry would say something like, "This-- you gave this revelation over here, but it seems to contradict over here." And God would say, "Well, it's-- this is what I was up to over here, and this is what I was up to over here, and if you'd stop looking at it as either/or, a broader, bigger view seems to come into play."

Jerry L. Martin [00:13:16] Yeah. I was always told in those moments, which happen often here, I'm an old logic professor, God says think more both/and unless either/or. And so that's really a key, you might say, to life. (Laughing) You have to know how to think about all of these most profound questions is don't parcel it off into opposing views, at least not prematurely. You know, it might be wrong interpretations or wrong ways of living or something, but start trying to take it all in and without sorting it into the true and the false, you know, two columns where everything goes on one side of the other. No, just hold back and take it in. In fact, one of the earliest prayers was I was told how to read scripture.

Scott Langdon [00:14:06] Mm-Hmm.

Jerry L. Martin [00:14:07] I was told to go read these earliest foundational scriptures, and I was given an instruction about how to do that. And it was, of course, to read them kind of prayerfully, but don't analyze them. So don't analyze metaphors, don't analyze sources, just take them in, and just read them and see what comes to you. Just take them in.

Scott Langdon [00:15:00] I keep coming back to God's first word to you- listen.

Jerry L. Martin [00:15:06] Yes.

Scott Langdon [00:15:07] Because that has-- that has made the single most significant impact on my life, I think ever. Just the way that that has come to me during the course of working on this project. So, I could say all my life, you know, we've been told, you know, listen more than you talk, you have two ears, and only one mouth, and all of those things, and some people get that instinctually or just know that or some people, a different kind of instruction hits them in a different time, maybe some people never picked that up. For me, it was working on this project and hearing the word LISTEN. And what I've been contemplating this week, especially listening to these last couple of episodes in preparation for this one, is that God doesn't say to you, "Listen, so that you'll know which way is right." Or, "Listen, so you know what to do." Now those things are true I think when we do listen to God, we hear instructions, but I mean just that, the very first thing God says in and of itself is just listen. And I started thinking this week a lot about when I am ready for change and insight and for God to really do something in me and with me, it's when I get to a place (and I haven't, I realized I don't think I've ever consciously known that I've been doing this, but...) really listening and not listening for something.

Jerry L. Martin [00:16:42] Right.

Scott Langdon [00:16:42] If I've listened before, it's OK, I'm listening for-- all right, tell me what to do, I'm listening for instruction, I'm listening for... but when I just listen the other religious traditions, to other people in their suffering, to other people in their victories, to other people's criticisms of me too, I mean, whatever it is to just listen in that place of complete listening and not listening for something. There is a being in touch with God in a way that I'm not when I'm listening for instructions or listening for this or that. Does that make sense?

Jerry L. Martin [00:17:18] Yeah, sure. If you over specify it, listening for, you're almost anticipating the answer.

Scott Langdon [00:17:24] Right.

Jerry L. Martin [00:17:24] At least what type of answer is going to satisfy the question, and you're not, you might say, giving God free reign. You know, just listen as almost-- put yourself in a listening mode and a paying attention to mode. It's almost like the esthetic attitude, you know, just step back, take in what comes and let it be whatever it is, and it might not be an answer of what to do or which religion or which/what to believe. It might be a moment of contemplation or appreciation, or sometimes I even get the instruction- do nothing. This is a time for doing nothing.

Scott Langdon [00:18:40] Also, in episode 70, the first part of your fourth dialogue with Richard Oxenberg, you talk about the idea of God developing. And that I know for Jerry, for you, you know, that was a difficult thing to deal with to begin with, and Richard has a difficult time with that, and quite frankly, I have a difficult time with it too. I struggle with this idea of God being young, of God developing. Your explanation to Richard is, you know, God is coming into being. What's coming into being is also the world. That God is the world and in a sense is standing back from the world, but it's all God's. So if the world is developing, if humanity is developing, if-- and it's undeniable, I think it's undeniable that humanity has developed over time the way we talk about time, so it's clearly developed. And if God is essentially us... if there essentially is nothing but God why would we not want to talk about it as God developing?

Jerry L. Martin [00:19:50] Sure and part of the whole story of the key, you know, what is the story, God: an Autobiography? You know, tell my story was the first thing he ever said, and I thought your story? (Laughing)

Scott Langdon [00:20:02] Right.

Jerry L. Martin [00:20:02] I had no idea what this would be. Well, what is God's story? It turns out to be the story of God's interaction with people. I mean, at first, its interaction with just swirls of matter, and energy, and so forth. But the sharp development is when God is interacting with human beings. And then God makes mistakes at the beginning and kind of learns his role. And in fact, through the different religious traditions, the different cultures reacting to God differently, God learns different aspects of God's self, which is an amazing thing. From the Chinese, that's when God is a kind of harmony, cosmic harmony, God kind of-- see it's as if God says, "Yeah, I guess I am a kind of cosmic harmony." (Laughing).

Scott Langdon [00:20:55] Mm-Hmm. Yeah.

Jerry L. Martin [00:20:55] And then God becomes more cosmic harmony in kind of response to that recognition. Kind of, you know, moves into that role, I suppose. I mean, I think we all have these experiences. I was thinking, you know, the person becomes a great stand up comic probably found other kids laughing in junior high, you know, in the eighth grade, they find it funny. And so he learns, Oh, I'm funny! And by learning to be funny, and then they laugh when I talk this way and so forth, then he learns to be funnier- right? And ends up being a successful standup comic. Well we all have these different aspects of ourselves that come into their own as people respond to them. God's development is mainly becoming fuller of God, fuller of God's self in that course of interaction. You know, I'm told the subjective is essentially intersubjective. You develop the self in response to other selves, and God is subject to that as well, and that's what makes the whole history of the world a dramatic story. You know that this having separated out other from same, you know, (or as I think Oxenberg sometimes puts it, and maybe not in that particular dialogue) but it's as if the one is divided itself into many parts, and now it can react with the parts because the parts have their own freedom, autonomy, integrity, even though they're aspects of the divine.

Scott Langdon [00:22:38] Mm-hmm. Right, right.

Jerry L. Martin [00:22:40] So that's the story in a sense of why it's dramatic and meaningful. And we're doing our best ,we as individuals, and God in working with us- all doing our best.

Scott Langdon [00:22:54] Yeah, that analogy, and I really like it a lot, you talked-- when you were talking with Richard about Richard being a teacher and how, you know, Richard's a good teacher. How do you know you're a good teacher in that response? Same thing with the standup comic. You know you find that you're funny and... I have played in my career really two types of characters, either funny comedy characters or really serious villains- bad guys.

Jerry L. Martin [00:23:23] Oh, you're a villain, Scott!

Scott Langdon [00:23:24] Yeah, you know. You know villain or--

Jerry L. Martin [00:23:26] Who would have thought?! (Laughing)

Scott Langdon [00:23:27] Or a comic. Right, right? So, when I think about this idea, I think about the fact that when I make people laugh, and they're laughing, that makes me feel good. Oh comedy, that's good, that's great. And so when somebody sees me around and they think he's a funny guy, but if you reverse that, which is also true is that sometimes I come across as very scary, very frightening, and you don't want to come around me. And that makes me not feel so good--

Jerry L. Martin [00:23:58] Right.

Scott Langdon [00:23:58] Because I don't want, I don't want to feel that way- right? So when I think about God, I think about it makes me feel good when people laugh, and it's funny, and that's a good thing, but only in relation, I would think, to the other, which is I don't like the feeling of being seen as scary and funny. You know, when we think about God in that way, God has to have both sides of those things too in order to understand how God is developing in one way or another. Am I in the ballpark with that idea?

Jerry L. Martin [00:24:32] Very interesting. I never thought of that. God needs both sides. God needs a scary side. God certainly needs an authoritative side- that was part of my first experience. And that authoritative side comes across as stern. And I suppose, like all of us, everybody who's a parent has this experience. You need to be authoritative without being scary. You know, without actually frightening your kids, and yet they need to know when you mean business in setting down a role. But there's also just the awesomeness of God. It wasn't my-- my experience was almost like talking to somebody on the phone, but if you read, you know, countless reports of religious experiences, people often quake in their boots, you know?

Scott Langdon [00:25:21] Right, right.

Jerry L. Martin [00:25:21] They kind of almost want to run away. One story told in the book is the Apnea Indian, who sees a God and recognizes him right away, and the God seems to want to say something, but He's too scared, and finally, the God gives up and goes away, comes back to him later. But anyway, his response was just to freeze, to freeze in his boots.

Scott Langdon [00:25:48] Right.

Jerry L. Martin [00:25:49] And, so, I don't know, I haven't thought much about that. As we learn in the full story, when we get to Zoroaster and then back to certain aspects of the Old Testament, that God does have these different sides. And this isn't just how we react, but it's like God... has to integrate his personality if you speak in very human terms.

Scott Langdon [00:26:15] Right.

Jerry L. Martin [00:26:16] Because we all have some of this, we've got some aspect of ourselves that simply are not well-integrated with other aspects, and they can just pop out. (Laughing) You know?

Scott Langdon [00:26:26] Yeah.

Jerry L. Martin [00:26:27] Uninvited, and spoil a situation, maybe. And God is going through that, dealing with his own incompleteness. It's not really an evil side, but the unintegrated part can act like evil, you know, seem like evil, can have bad consequences. And so God is dealing with that, and in part, the interaction with us. It's like how personalities develop. You become more mature, and you learn to control some of these bad aspects of yourself, these unintegrated parts, in part by dealing with people, learning to deal with people more successfully, and developing yourself in response to that.

Scott Langdon [00:27:13] And if we take the- if we take the say, the biblical story, and you guys talked about, and we've talked about before, the Abraham story and what God is asking Abraham to do. And then that same God, later on, is going to destroy the whole city and, you know, is talked out of it (to, you know, to a large degree) well, "I'm just going to wipe out the whole thing." Well, maybe if you found, you know, 10 people is one, you know... and it seems as if- if you take the story for what it is, if you take it on its face, God is being talked out of it.

Jerry L. Martin [00:27:50] Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Scott Langdon [00:27:51] His interaction with Abraham makes a difference and changes God's attitude. God gets angry and- and I can understand that. I get- there's a frustration when things don't go the way I think things should go. Especially when I know, through my experience, that if you don't take that path, your life will be easier. Like, you know, if it's a friend or my child or whatever, it's, "If you go down that path, I'm telling you it's going to be rough for you." And they do it anyway, and it's frustrating, and you can get angry, and I can imagine God being that way.

Jerry L. Martin [00:28:27] Sure, sure. And it's important to think, although there is a kind of eternal, you might call it, point of view about things, but the historic timeline is real.

Scott Langdon [00:28:40] Mm-Hmm.

Jerry L. Martin [00:28:41] The eternal point of view does not cancel out the reality of people changing over time, including God changing over time. So one has to, though that's another both/and, one has to take both of those aspects of time into account, and both are real. The eternal point of view is real. The linear point of view is also real, and people do change. And we all- we have that experience as human beings. And if you read the scripture without prior theological assumptions, that's what the scripture is telling you. You know, this is a story of a God who's a real being and having a real history, real interactions, and really changing. Sometimes regretting things. You know, he'll sometimes at a later point, regret that he did such and such. So, that's a real-life God that we are participating in, interacting with, that is both other and same as us. Kind of the basic both and of the whole God: an Autobiography.

Scott Langdon [00:30:22] In episode 71, which is the second part of your dialog with Richard Oxenberg, you talk about--and Richard brings up the idea of a God that needs to be worshiped, or should be worshiped now. And how does the God of God: an Autobiography, that speaks to you, how does that God fit in as a God to be worshiped? So if a God is developing, how do we worship? And essentially, what I was hearing, and what I was processing through, you know, my growing up and my theological lenses growing up, is this idea of a perfect God. And all-knowing omnipotent, omniscient, all of it, doesn't seem to leave room for a developing God. That would start out somewhere and have to learn anything. If you know everything, and you are ready-- then what do you have to learn? Thinking about this idea, I started to realize that one of the problems with having a perfect God is that I would get the mindset, and I think it's shared with many, of being concerned about what not to do.

Jerry L. Martin [00:31:34] Hmm.

Scott Langdon [00:31:35] So it was always make sure you're not doing these things, because if you do these things, that's not living up to the perfect standard of-- so forth, and so on. And because there is no way, and we're always reminded that we will never reach that perfection, but we always have to strive for it, but we'll never-- we're never going to reach it. It always keeps God at a distance, and always this isn't-- this is how I've taken it. Now, not everybody does. For me, what weighed heavy on me is that there will never be a time when I can ever get there. And so then it becomes, well, why even bother? And, so, when you expressed that you didn't, you didn't really think about the idea of God having to be worshiped, in your response to Richard's question, I found that even more interesting that God would give this revelation to you. Someone who is not an atheist, but also someone who doesn't-- who isn't hanging on to that notion of a perfect God, and the perfect way of knowing God.

Jerry L. Martin [00:32:43] It's also someone not-- it's a bit like your comments, Scott, about listen where you're listening for a particular kind of answer. This comes out of a certain religious frame where you say, "Well, the god I want is a god I can worship. I've got a religious niche, you know, already, a place on the pedestal (at the top of the pedestal) that is for this being I can worship. And, you know, they might say, every culture and every tribe or something, you know, is looking for a totem, you know, something at the top of the totem pole. But that's had nothing to do with my experience. I was not looking for a god to worship. I was giving thanks, originally, and then seeking guidance. And that's been my relation to God, essentially. What do you want of me, and what I'm told-- I've never been told, you've got to be perfect. I mean, that would just seem kind of ludicrous as a thing for God to tell Jerry Martin.

Scott Langdon [00:33:49] Right? Right, right.

Jerry L. Martin [00:33:50] You're supposed to be perfect. Go get perfect, get yourself perfect. I was told in one prayer, "Your only job is to do each day what I tell you to do that day, and if it's just to sit and look at the backyard, that's what you're supposed to do." None of it has to do with being perfect. The idea of a perfect God, well, I've forgotten the details now, but God says that's a nonsensical concept of God as a perfect being. It's simply nonsensical, that. The perfect being wouldn't quite be real. You know, if you want to just imagine, some imaginary, you know, thing, being that wouldn't actually be in the real world dealing with real people. And you look at our world, does it look like the world presided over by an omnipotent and benevolent, omniscient being? It doesn't look like that, does it? And so you get into all these theological conundra, ends of this... Can God create the object too heavy for God to lift? You know?

Scott Langdon [00:35:05] Right, right. (Laughing)

Jerry L. Martin [00:35:05] You know these are paradoxes. You can't quite play it out, literally, you know, logically, and of course, this problem of evil. Why is there evil in the world? Well, later in the dialogues, Richard and I are going to take up that question. Why is there evil in the world? Because you start with that kind of omnipotent God, it's very hard to account for evil and the world not being perfect. And you can count for human evil by the free will, but there are lot of evil that isn't human evil. There's just tragic injustice. A baby's burning in a hotel fire, and stuff. Of diseases that rampage the planet. So anyway, that simply is irrelevant to God's story, and the god's interaction with us. God isn't perfect. He's not asking us to be perfect. We're all learning our way.

Scott Langdon [00:36:09] When I think about worship, I think about listen. And being in a, you know, getting myself to a place where again, where I'm not listening for anything with any assumption, I'm just listening, just being, and I feel, you know, connected. And then there is the next step, I guess, the next situation, where now there is a doing. You listen. OK? And now what? Getting into the world, what do I do in the world? And one of the ways I have always learned growing up, you know, to get in touch with God in that way, to find out what to do or... is prayer.

Jerry L. Martin [00:36:45] Yes.

Scott Langdon [00:36:46] And prayer for me was always difficult and complicated as I got older. It wasn't when I was young, but when I got older- how to pray, if I don't say, "In Jesus name, Amen," did it count? Just things like that, that I took in as being important. But when I think about it now, prayer, I would think about things like pray without ceasing. That's a phrase you would hear in the church, and it would be, you know, we have to always be praying. And then I would say, "Well, how can I always pray without ceasing? I have to go to school, and I have to do other things. I can't always be praying." But this, now, I think about it differently when I think about what prayer is. You mentioned it's- God wants to know how it is with you. And, you know--

Jerry L. Martin [00:37:33] Yes.

Scott Langdon [00:37:33] Just having a time, where, whenever it is- is it God here? Is how it is with me. But there is that reciprocal, I think, when God is telling me how things are with God, you know?

Jerry L. Martin [00:37:47] Yes, you're very right.

Scott Langdon [00:37:47] We've talked about this a little bit before. Maybe it's the news, or maybe it's a friend who's giving me-- you know, I'll be saying, "God, this is tough on my heart, this is going on, I don't know about this, and that, and the other thing." And then maybe in the middle of that, I'll get a call from a friend, and I'll be like, "Oh, well, I'm praying, but I'll take this call." And I'll take the call, and my friend is telling me how rough it is with him.

Jerry L. Martin [00:38:11] Yes.

Scott Langdon [00:38:12] And is it... I get this notion, this nudge as if God is saying, "OK, now you were going on about your thing. Now, I want you to hear Myself," and it's only one aspect, it's my friend, but that's my job, right there is to be the compassionate listener that God was being when I was spilling my guts. And that prayer, it stops being like, did I say all the verses, right, did I say, "Jesus name, Amen," did I say, "Dear God," at the beginning? And it just becomes this conversation about, here's how it is with me, and then listening to how it is with God, and then also this other, I don't want to, I don't know... Ethereal. I don't hear an English voice like you had heard. But this just being open to listening to (sounds weird) listening for a feeling.

Jerry L. Martin [00:38:57] Yes.

Scott Langdon [00:38:58] So that listening and the doing start to get wrapped up into one another the more you listen.

Jerry L. Martin [00:39:05] Yes, I have friends I've talked to a lot because they're very spiritual and unlike me, have been religious their whole life, and they're very knowledgeable about things like spiritual discernment and so forth, and the hazards of the spiritual life. Anyway, the husband in that couple said (and the wife chimed in in agreement), is that "I'm thinking about God all the time."

Scott Langdon [00:39:32] Yeah.

Jerry L. Martin [00:39:33] And I remember when they said that I thought, well, gee, their way ahead of me, I'm not thinking about it all the time. (Laughing) But then, when I reflected more, it depends on how you define, a bit like what you're saying about prayer, Scott, depends on how you define prayer. How you define thinking about God? I'm not-- don't have the thought, God, always running in my head. But I realize, no, it's a bit like gravity or something. I'm not exactly thinking about gravity at all time. But I'm aware of gravity at all times, right? I'm taking it for-- it's the framing of my life and the fundamental reality of my life, and I'm aware of that at every moment. And then occasionally stop to pay direct attention to it, but that keeps me a little bit open, I think, to these nudges where I might not even know it's a divine nudge. But, you know, that my ear picks up something, and maybe a need of a friend as you're describing Scott, it might be a piece of music that's going to enrich my soul in some way, or something to do for Abigail, or who knows what it will be. It can be many, many things. But, you keep that openness to the Divine going at all times. I think that's, that might be a better way to put it. Doesn't have to be God on your mind, exactly, because that might be a confusing concept. But that- the soul being open, and not overly distracted by every other worry in life. Including, you know, your bad toe, or somebody you know, some elements of suffering. Because it is very hard to be open to the Divine at certain moments of life, but it's important because even in-- even at those moments, there is something God may have to communicate to you explicitly or kind of implicitly, and how you take it in.

Scott Langdon [00:41:34] Last week, we talked about an email that we got from Wayne. And that is at the heart, well, it's, you know, it's at the heart of everything, right- the listening, and the discerning and so forth. And Wayne tracked his life a little bit through the way he was feeling he was being called by God. You know, things went south with his business, and then he was being called into a kind of ministry, and then that kind of ministry started to fold, and then it was being called to the inner city and so forth. And along the way, it seemed like one of his struggles now that (when I was listening back to the episode) it seemed like one of the struggles was what we were just talking about today. The idea of listening for something. He talked about it as testing. You know, I put-- God said, you know, essentially, "I want you to move to the inner city. I'm going to find--" You know, because I was like, "God, I need a job, and I need a house for my family, and if you're going to want me to go there, then you've got to take care of that." And God took care of that is how he described it, right? And we wondered about the test idea. Was he putting God to the test? But I wonder if, there might be something to this kind of listening... When is it time to listen for the direction, right? There is the listening. There's that great preacher story about the preacher there's a flood in his town and everyone, he gets everyone out first, and then he-- the car comes by, he says, "No, I'm going to wait for God to save me," he goes up to the second floor, and the water's come, and there's a boat. He said, " No, I'm going to wait for God to save me." And finally, a helicopter, and, "Oh, I'll wait for God to save me." And then he drowns, and he says, "God, why didn't you save me?" "I sent you a car, a boat, and a helicopter. What else do you want?"

Jerry L. Martin [00:43:18] Yes, exactly, right. What a great story.

Scott Langdon [00:43:21] I love that one.

Jerry L. Martin [00:43:22] Yeah, that's how it is, and this really goes back to your, you know, am I listening in this overly object-directed way? You know, listening for X when maybe what God needs to direct my attention to is why.

Scott Langdon [00:43:36] Yeah.

Jerry L. Martin [00:43:36] You know something completely different what I'm listening for. And this guy has a fixed idea of what it means for God to save him. And in Wayne's story, the people at his church turned out to have a very fixed idea of what it means to save a person. He has the most moving story of how, through his efforts, bringing inner-city people in, teaching them to make furniture, and people who felt there- that they had been worthless their whole lives because (in one key story) that's what his father had always told him. And this piece of furniture says otherwise. I think he made a beautiful object in this Cherrywood piece of furniture. And the people at the church with this narrow conception of what it is to save souls says, "Well, that doesn't count." Well, phooey, that is what counts. And as Wayne says, "It saved me too." (Laughing) You know?

Scott Langdon [00:44:34] Yes, yes.

Jerry L. Martin [00:44:34] It's all kind of work. You know, it's not just to go through the rituals of the church or recite creeds or any of that stuff. It's God active in the world. You as a divine agent, active in the world is a lot of it. It's not the whole of it. Contemplated life also has a role, Many other kinds of life, aspects of life, have a role. But he's really fulfilling God's purposes, and it's manifest, and it's deeply moving.

Scott Langdon [00:45:02] Yeah, yeah. In that story that you just mentioned that the folk who-- the guy who made the piece of furniture, he felt really great, and Wayne felt really great giving him that gift. You know, Wayne also thought-- And I believe, and I think we could argue, especially based on what we've talked about today, that that is how God is with us as well. When something-- when we take a step to toward healing, toward becoming a better person toward, you know, giving and rece-- When we get it, quote-unquote, you know?

Jerry L. Martin [00:45:35] Yeah.

Scott Langdon [00:45:35] In those moments, I feel like God must also feel the way I would feel when my daughter or my son gets a concept or gets, you know, I see my daughter being such a wonderful person, and my son helping out other people. And I get this sense of, you know, we call it pride, but I just think it's this extension of my heart. You know? Yeah--

Jerry L. Martin [00:45:55] Well, yeah, it's a kind of joy, a very appropriate joy. You think of how God must feel in that story Wayne told about the guy making the furniture. It saved-- the guy had saved Wayne, I mean, it changed their lives. It was a transformative experience. That's what religion is supposed to be about. Spirituality is supposed to be about transforming the self to a higher level of self. Well, think of the impact on God. God would have to be cheering and thinking, "Yes!" You know, "The universe is rising (you might say) in this moment." Because every one of these moments counts, it counts almost infinitely, you might say, and at the same time, I mean, I don't want to beat up on a church I don't know about, but just taking the story as it sounds, it sounds as if the church had this very narrow view. They're failing to appreciate this work, and I would think God would sort of wince, and want to, you know, get their attention, do something to get their attention--

Scott Langdon [00:47:04] And maybe get frustrated, like we talked about before. Yeah, yeah.

Jerry L. Martin [00:47:08] Yeah! You get frustrated. And you can't get their attention because they're so locked in their own, maybe even sense of spiritual pride, their own sense of their religion has the one right way. There is a one kind of idolatry is the idolatry of belief. They think they're worshiping God. They're working and worshiping their own set of beliefs. Well, that's a terrible thing to do. And God must-- yeah, I think you said it exactly, Scott. God must get very frustrated. And some of those moments that the prophets express in the Old Testament are moments of frustration. You know, why won't you people pay attention, and do right? You know?

Scott Langdon [00:47:53] And all along, there are also victories, and triumphs--

Jerry L. Martin [00:47:58] Yes.

Scott Langdon [00:47:58] That go along the way that, you know, I think about the last, you know, seven to eight years have been very difficult for me. A lot of change in my life, and it becomes much more clear that the day to day aspect of just listening to God becomes so much more important than any projection I might have about the future. That when I ground myself in the present moment, in the way that you're talking about just sort of being here, just listening, even if you know, God says, just sit in the backyard, or... And I think about the time also when you were in the car driving somewhere, and you heard a thing that sounded like a gnat or whatever, and you didn't know. And later on, God says very quietly, "Listen, (you know) even when I whisper." And that, to me, just in the storytelling of it, told me God is saying there turn up, turn up the volume even more.

Jerry L. Martin [00:49:00] Good point.

Scott Langdon [00:49:01] Turn down the volume of your own thinking mind because I would imagine when you're driving to work, you're thinking about the other cars, you're thinking about what work you've got to get turned in, and deadlines here, and that. All this stuff that's outside of the present moments, the future concerns about the past. And God is just saying, you've got to turn me up when that starts to get juiced.

Jerry L. Martin [00:49:21] Yeah, that's exactly right. That's exactly right.

Scott Langdon [00:49:24] Well, I'm very excited about doing this again. I'm very excited about folks writing in and talking to us about their experiences. So if you are listening and you would like to talk about your experience with God, please email us at questions@godanautobiography.com. And we'd love to hear from you, and Jerry can't wait to talk to you again.

Jerry L. Martin [00:49:45] Very good. We are learning a lot.

Scott Langdon [00:49:57] Thank you for listening to GOD: an Autobiography, the podcast. Subscribe for free today, wherever you listen to your podcasts, and hear a new episode every week. You can hear the complete dramatic adaptation of God: an Autobiography, as Told to a Philosopher, by Jerry L. Martin by beginning with episode one of our podcast, and listening through its conclusion with episode 44. You can read the original true story in the book from which this podcast is adapted God: An Autobiography, as Told to a Philosopher, available now at Amazon.com, and always at Godanautobiography.com. Pick up your own copy today. If you have any questions about this or any other episode, please email us at questions@godanautobiography.com and experience the world from God's perspective, as it was told to a philosopher. This is Scott Langdon. I'll see you next time.