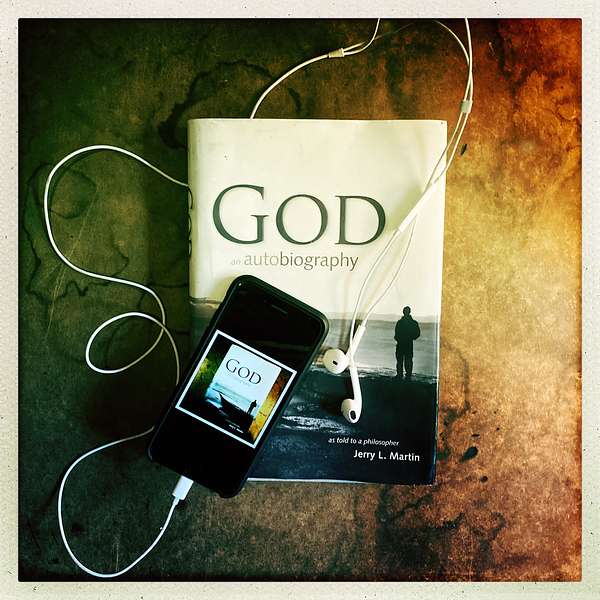

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

119. The Life Wisdom Project | The Drama of Suffering | Special Guest: Dr. Christopher Denny

Jerry and Chris share a conversation of life wisdom, using dramatic metaphors, looking at life mysteries, cynicism, and the value of a trusting community. Find some answers to the timeless real-life questions of the thinkers and seekers.

Dr. Christopher Denny is Associate Professor of Theology and Religious Studies in New York, Associate Editor of CTS journal Horizons, and author of A Generous Symphony: Hans Urs von Balthasar's Literary Revelations.

Do you feel God is still speaking? How are you an ambassador for God? Share your story or experience here.

MEET THE GUESTS- Dr. Christopher Denny

FIND THE SITES- Theology Without Walls | What is God: An Autobiography

BUY THE BOOKS- God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher | A Generous Symphony: Hans Urs von Balthasar's Literary Revelations | Theology Without Walls: The Transreligious Imperative

LISTEN TO RELEVANT EPISODES- [Dramatic Adaptation] I Ask God What We Are To Him [The Life Wisdom Project] Situational Attention

God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher, is written by Dr. Jerry L. Martin, an agnostic philosopher who heard the voice of God and recorded their conversations.

The podcast began with the Dramatic Adaptation of the book and now has several series:

- Life Wisdom Project-How to live a wiser, happier, and more meaningful life with special guests.

- Two Philosophers Wrestle With God- sit in on a dialogue between philosophers about God and the questions we all have.

- What's On Our Mind- Connect the dots with Jerry and Scott over the most recent series episodes

- What's On Your Mind- What are readers and listeners saying? What is God saying?

WATCH- Dr Jerry L. Martin and The Theology Without Walls Mission

#thelifewisdomproject, #godanautobiography, #experiencegod

Share Your Story | Site | Facebook | Instagram | Twitter | YouTube

Scott Langdon: [00:00:17] This is God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. A dramatic adaptation and continuing discussion of the book God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin. He was a lifelong agnostic, but one day he had an occasion to pray. To his vast surprise, God answered- in words. Being a philosopher, he had a lot of questions, and God had a lot to tell him. Episode 119.

Scott Langdon: [00:01:08] Hello and welcome to episode 119 of God: An Autobiography, The Podcast and the fifth edition in our series The Life Wisdom Project. I'm Scott Langdon, your host. And in this episode, Jerry has a conversation with Dr. Christopher Denny, Associate Professor of Theology and Religious Studies at Saint John's University. The two discuss episode five of our podcast titled I Ask God What We Are To Him, where we hear Jerry and God talk about suffering and how God co-suffers with us. In this episode, Jerry and Chris dig into the heart of the themes of episode five and we deliver to you now their wonderful discussion. Remember, you can hear the complete audio adaptation of the book any time by beginning with episode one of this podcast and listening through episode 44. We begin with Jerry speaking first. I hope you enjoy the episode.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin: [00:02:02] I'm very pleased to have Christopher Denny for this episode of Life Wisdom. I well remember how I first met Christopher. He had written a brilliant paper on two important theologians of our period, Francis Clooney and Raimon Panikkar, and I thought, this is someone I want to get to know. He was at a conference. In fact, he was chair of the conference that I was attending of religious studies scholars and theologians. So I approached him and introduced myself and said, you know, "I read your article. I would love to talk about it." And from that time on, we had been friends. And then I got familiar with some of this other work. He's written just a splendid kind of tour de force on one of the greatest theologians of the 20th century Hans Urs von Balthasar. And it was a challenging project because Balthasar worked a lot with literature and not just literature, you know, in a religious tradition, not just, you know, Christian themes and Shakespeare or something, but literature all the way back to the pre-Christian era, Greek tragedy and all the way up to people like the German romantics, Gerta and so forth, which meant that Christopher had to not only know the theology of Hans Urs von Balthasar, but had to also master this enormous corpus of literature, which he seemed extraordinarily able to do often in the original languages. So I thought, wow, what a guy. And when we first started the Theology Without Walls Project, Christopher came to the very first meeting. He's been rapporteur for that group's annual planning meeting and has made very important scholarly contributions to it and to our discussions. So anyway, I couldn't imagine anyone better for this topic episode that we're dealing with them to be able to talk to Christopher Denny and to take in his wisdom, which I knew would be unique. Let me start Christopher Denny with a heartfelt thank you and tell you how delighted I am and how appreciative I am of your willingness to do this. That is a heartfelt expression of appreciation because this is not the kind of normal academic work that you get academic credit for at university, but it is a service, I think, to our listeners, and everyone needs help in life. And one thing everybody needs is life wisdom. And so as you listen to this episode, Chris, what struck you about it?

Dr. Christopher Denny: [00:04:58] I think what sticks foremost in my mind is the fact that when we talk about wisdom and about religion, we're always cognizant that religion is fundamentally a response. A religion is not a rayified object. But religion is something that, from the Roman etymology of the word in Latin, it binds us to an encounter, if we put it that way, with someone, some things, some reality larger than ourselves. When you read a lot of contemporary religious studies or contemporary theology, that mode of dialogue that you foreground in your work has been pushed aside. And yet, if we go back to the foundations of the Greek philosophical tradition, there's a reason why Plato wrote in the dialogue format and why Anselm uses the dialogue format, why a contemporary writer, for example, like Elizabeth Johnson uses the dialogue format. And so it was just, I think, really refreshing to read a dialogue and not just a monologue- another scholarly monograph. Right. Monograph. Single writing. Writing alone. That's what I thought.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin: [00:06:34] Well, well, that's what struck Scott Langdon when, you know, he turned out to be an actor, I got him just to help with social media, but he was an actor, has his own intense religious journey. And when he read God: An Autobiography it struck him because of that dialogic feature. You know, it's a person talking to God and God talking back. It struck him as dramatic. And we even considered shaping it into a play or something. But I thought, no, then it would look like fiction. This is not at all fiction. But we thought, this kind of radio theater form can bring it alive without necessarily implying it's fiction, which it is not. I mean, I'm telling it straight and it's also not a vehicle for some views I had because I had no views about these things when the experience began. But religion is a response. It's answers to questions. Right. And that means that presumably people had before the religion came along or before encountered presumably the religion is speaking to some questions they already had. It's not engendering the questions, but it's responding to them- would that, something like that be your view?

Dr. Christopher Denny: [00:07:49] I think properly expanded, yes. One of the things that a lot of philosophies of religion do in the modern period is they like to formulate the religious quest in explicitly existential terms. Who am I? Why am I here? But that doesn't exhaust the range of questions. I think Tillich was onto something when he defined religion as ultimate concern. Concerns aren't always verbalized as questions and concerns somehow in many cases deal with more, shall we say, tangible wants. You know, going back to the ancient world, people look to religion for how can I ensure a good harvest, childbirth? And so I do think that so long as we're cognizant of the fact that questions aren't always those of the armchair scholars, I think the idea of religion as a sort of question or addressing a felt human need is certainly a particularly compelling way to think about what religion is.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin: [00:09:06] Yes. Yes. There are several needs that surface in this episode. I guess you call them needs concerns, maybe use that ultimate concern type of language. One’s suffering comes up toward the end. And so the question is, what do we learn about suffering? And it's a key quote, I think. "Suffering is the law of growth in the universe." Well, that's a rather different perspective on suffering. And I know when that was published in a little piece I did in a Richmond newspaper, somebody wrote in ridiculing, that's the most ridiculous thing they ever heard. Did that make any sense to you? Do you see any life wisdom in that kind of thought?

Dr. Christopher Denny: [00:09:53] Sure. I mean, when we go back to the Greek tragedy and I believe it's in one of Aeschylus' plays, the chorus says, "With suffering comes wisdom. You know, suffering is one of those things where the meaning depends on the context. So we can identify suffering as being masochistic or as neurotic if we only look at suffering in an individualistic guy. So if I were to sort of harm myself in some way, God forbid, I would be seen as psychologically in need of treatment. But if I were to train to run a marathon, for example, which certainly involves a lot of suffering, or if I was to volunteer on a night shift to go feed the homeless, that would certainly involve a disruption of my schedule and also suffering. And I think when people see the communal context of suffering, they see suffering in a completely different light. And so if God is someone who is a being for others, then to say that suffering is inherent in existence is a very, very different characterization than you might find, say, in a lot of popular psychology these days, where the goal is to overcome suffering. I'm not sure that's possible.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin: [00:11:24] Right. Well, the advice here and it seemed to fit the Aeschylus quote, you mentioned at the beginning is to find the wisdom in suffering is to learn something from your suffering. And in another chapter– I was led through and I was told to go do that. Look at a period with which I suffered. Now, what did I learn from that? And so the things we have to go through in life, even the negative things have something to teach us. So that's, I take it as one implication of that and puzzled me greatly. Why do– God seems like a completely self-sufficient being. Why does He care about us? Why does He care about whether we pay any attention to God? He's set. That's just how my naive understanding of this impermeable, impermeable isn't quite the right word, but unchanging, divine being who's only got all the perfections, and I guess I'm looking for impassibility or something, not affected by anything. Then why is He affected by whether our disobedience, whether we're not paying attention? And this episode sort of addresses that.

Dr. Christopher Denny: [00:12:45] One of the things I do in introductory survey courses with my undergraduate students is to tell them about the Council of Nicaea and what I call the crisis of classical theism. So as Christianity becomes inculturated into the Greco-Roman world in its earliest centuries, you have a collision between this what we'd call, from a philosophical perspective these days, a classically theistic formulation of God in which God is omniscient, omnipotent, omnibenevolent. And then a sort of Judeo Christian biblical notion of God in which the surface language of the Jewish and Christian scriptures reveals a God to be anything but the classically theist God the philosophers are comfortable with. And ultimately, I tried to tell the students that Christian theologians in the Middle Ages tried to resolve this conundrum by redefining what it meant to be God. And so if God is conceived of as independent, fundamentally, you know, walled off, if you will, on some sort of olympus from the human race, the Christian story really doesn't make any sense. And I think historically, when that conception of God has become dominant, you start to see Christianity wane. This was the argument in a book by Michael Buckley a couple of decades ago in which he sort of blamed modern atheism on the rise of deism in the Enlightenment. I think what good Christians have tried to do is to say that God, by God's very nature, is diffusive of goodness, is diffusive of love. God is fundamentally in relationship. From a Christian perspective, this is seen in the Trinity, right? God is not a person but a community of three person. That notion of relationality being intrinsic to the question of God's very existence is, I think, one way I, at least as a Christian, try to deal with, you know, your question, why should God care? And the answer I come up with, which leads to other questions, is because that's who God is.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin: [00:15:16] Right. Right. Relationality is essential to God's being I'm told in a different chapter. We were not doing an episode of this time, but that's essentially God's nature. But this particular episode seems to take one step beyond that, which is- you are My face onto the world. You know, it's hard on people for Me to love them. I need you to do it for Me. God says here. And in fact, you are My eyes and ears. You know, my wife Abigail, sometimes says, "God can't mail a letter." So if you want something done in the world, you mainly have to think, this is our job. This is where somebody, you mentioned giving food to the poor at night, and so forth. Well, that's our job. You can't just pray for Manna from heaven. We have to go do something to help our fellow man. And even here the mentioning of Jesus how, you know, I wondered why the thing about anger, how could this, you know, Jesus is God, how can God just be angry? That seems like a low level emotion, not a sublime emotion. And, you know, he curses the olive tree and all these kinds of things, the money changers. And one of the things I'm told is, well, he's an example of how a finite human creature, a human being, because he's in fully human form, even if he's incarnation and subject to all these feelings and desires and emotions that we all are, how a being with those kinds of limitations can nevertheless give boundless love. And I guess one of the lessons I was drawing from that is, well, we're all very limited beings, right? But we can all give some love. And in fact, we can probably give more than we think we can. We don't have to just feather our own nest, even though, you know, we have to pay attention to our nest, you might say take care of the business of our own lives, but in addition to that, we can do a lot of self-giving to others.

Dr. Christopher Denny: [00:18:21] In the Book of Genesis chapter one, we read that God made male and female in God's image. A lot of times when people in telling the Christian story want to talk about God's image, they skip ahead to a very rarefied conception of what it means to be a human being, one that owes a lot more to Greek philosophy than it does to the Bible. And so I'll ask students, well, you know, what does it mean to be made in the image of God? And the students generally will begin with responses such as, well, we're rational or we have free will. But the original word in Genesis chapter one for image is tzelem. And in ancient times, biblical Hebrews' word tzelem referred actually to a carved statue, if you will, of a near Eastern King that would be paraded around the royal domains as an extension of the monarch's authority itself. For a contemporary analogy, when you go into a federal office building these days in the United States, you will see in the lobby a photograph, an officially authorized photograph of the president of the United States, which is in many ways the tzelem of our contemporary Commander in Chief. And so when we think about that image of God, you know what that means for humanity, then I think it becomes much more earthy and tangible. Because to talk about exercising God's domain in the world or having a share in God's domain makes it more comprehensible why being in a relationship with our fellow images of God is God-like.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin: [00:20:26] And it places obligations on us. Right? One reviewer reviewing God: An Autobiography for a parenting magazine, of all things, took from it the message, passages like this, the message we are God's ambassadors and you know you're carrying the image of God. That would be a kind of one thing an ambassador might well do or speaks for God, my ruler, I mean, speaks for the ruler, for the king, and his behavior reflects on the king whom he represents. And the person thought, what a wonderful message for our children, that we bear that royal imprint, you might say, and we have to kind of live up to that. You know, it's a blessing, of course, because it shows kind of our potential and role, but it's also a burden in the sense of you're not scott-free. You have responsibilities and you can live up to them or you can fail them.

Dr. Christopher Denny: [00:21:34] And we see shortly afterwards in the Genesis story that the man and the woman fail to live up to their tzelem calling. So it's always a challenge and one in which we have to be attentive and self-critical. Have we sort of foregrounded our response to the ultimate or have we sort of taken a shortcut to make the ultimate synonymous with our own egos?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin: [00:22:00] Sure, sure. That's very easy to do. And I sometimes think in terms of the idolatry of belief, because you can also, it's not just ego, or maybe ego is behind this, but it's where instead of kind of worshiping God, people are worshiping their own belief system, you know, their own creed or their own denomination or their own liturgy. In ancient Britain, or Britain in medieval Britain, they almost came to blows over which day the Sabbath was. And there is a minor civil war over was it Friday or Saturday? You know, I mean Saturday or Sunday? So anyway, people can be very attached to their belief systems and that can be a block not only in their ability to reflect the divine and to be an appropriate image of the divine, but their ability to fulfill the function of loving other people, which again in this episode, God needs that. Needs us to do that for Him. I was told in another chapter, or maybe in this chapter and wasn't picked up in the episode when I'm asking God to love me in some context I think in which I feel at risk, He says, "Let Abigail love you. I will love you through her." But that is concrete, that is concrete, that kind of thought.

Dr. Christopher Denny: [00:23:41] Yes. And I think the danger of speech about God, which another name for that is theology, is that we start paying more attention to the speech and less to God, you know, the ultimate, what have you. And that what originally was a responsive mode of existence becomes a sort of self-centered mode of existence in which you sort of become enamored of your own thought. And I think in some ways, the Abrahamic traditions are particularly susceptible to this problem inasmuch as they have what we call a cannon, right? God spoke certain times and then God may speak at other times, but not in the same way or with merely derivative authority. And I think the real challenge is for traditions such as these to foreground their own traditions and experiences that have been mediated through the community, while at the same time remaining responsive to the concrete others with whom they live with whom we all live. The, I believe it's the United Church of Christ that several years ago came up with a slogan, "God is still speaking."

Dr. Jerry L. Martin: Is still speaking?

Dr. Christopher Denny: [00:25:12] Still speaking. And I thought, you know, even though that sort of pitched a tent in the sort of moral and intra-Christian debates over changing morals around sexual activity and so on, I thought in and of itself, it really, I thought, was unassailable. I don't know of a single Christian who could deny categorically that God is not still speaking and still claim to be a Christian. And I can't speak as a Jew or as a Muslim, but I would be very confident saying that would probably be an assertion that the other two Abrahamic religions would hold as well. Allah is still speaking. You know, the God of Israel Adonai is still speaking. Where? Well, that's the challenge to go find where that speech is happening.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin: [00:26:04] Well, that's in a way, I think that's a very important insight. And I'm glad they were saying that. It's crucial to me because here is God speaking to me. And everyone, every reader or listener has to decide, well does this sound like God to them? You know, that's the challenge of spiritual discernment, which I immediately having this experience ran on, being an epistemologist for one thing, is this the real deal? So I called a friend who I thought was knowledgeable about such things, since I was not interested in religion, had not followed all this. And he said, "Oh yeah, that's the problem of spiritual discernment." But this very chapter is what led me to where we opened this particular episode, which was, you know, is this the real deal? Is this really have--And I never, I'm not quite attracted to the view of it's God speaking that every single word is pristine and eternal and infallible and this, that and the other thing. This is all filtered through me. I mean, I'm very aware of there's a medium here, and I'm the medium for this particular set of messages. And God uses, speaks in Jerry Martin American English, you know. Well, you can't think that's how God talks to everybody. That's not very plausible. And God is answering my questions. Nevertheless, I feel this is a message from God and a very important set of messages from God. But I then worry, okay, is it the real thing? And Monsignor Guardini, in this very nice book on The Art of Christian Praying or something, addresses that question and says it can happen to you. And it always sounds as if he's talking about a situation where it's like a monastery or somewhere, everyone's doing a lot of praying and suddenly, there is always a kind of a wall there. You're praying and sending messages to God. All of a sudden that God seems to be present to you, and then you run and ask, you know. But my question is this, "How do I know it's the real thing?" And Guardini gives a very nuanced- you can't believe every voice you hear, and yet, you can't doubt every voice. If you doubt every voice, every occasion of divine presence or divine messaging of whatever kind can be a nudge inside or a voice of conscience inside saying, you've got to do this, but if you ignore them all, you're going to-- you're missing out on too much. You know, it's the problem of skepticism of the Cartesian program, of universal doubt. If you doubt, doubt, doubt, you're never going to get anywhere unless you have a mythical certitude that he then comes up with. But the kind of skepticism that we're heavily infected with in our culture really is not workable as a path to truth because you're skeptical and thereby avoiding certain errors, but you're also not taking in all the truths that are there. And anyway, the advice of Guardini was he taught you know talk to your elders, talk to them, but in the end, go back and listen, and just calm down quietly, listen and pray about it, and just trust that God will kind of lead you along in the right direction. Does that make sense to you, Chris?

Dr. Christopher Denny: [00:29:48] Sure. I mean, the question about a prophet's reliability is not a new one, and it predates Descartes by millennia. I mean, we see it in the Tanakh with debate. So between Elijah and the priests of Baal and the way there that truth is determined is through this miraculous intervention on Mt. Carmel. In the first century Christian texts of the Didache, you can see that this early community for which these instructions are written is really concerned about how to distinguish between true prophets and false prophets. And the writer of that text indicates that ethical behavior that really will be the criteria to determine a true prophet from a false prophet. But it's really only in the modern era that we see people like Descartes and Hume elevate the principle of skepticism to this default position. And it's at that point that I'm reminded of a line one song by Bette Midler in her song, The Rose. "It's the one who won't be taken and who cannot learn to give." So the skeptic, I think to echo your point here, certainly it's hard to put one over on him or her. But if you walk yourself off into solipsism, you know, it's hard to be a tzelem for others. You ultimately have to determine what your fundamental orientation to the environment in the community around you will be. Are you going to be the one who wants to protect, or are you going to be the one who tries to avoid suffering at all costs, or are you going to be the one who's going to be vulnerable, which will certainly lead to suffering? And are you going to be the one who's vulnerable to being mistaken or learning that you've placed your trust in a religious figure who has let you down? That's a real risk. And that just comes with the territory of what religion is.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin: [00:31:57] Well that's the territory of an awful lot of life. As you were describing that, I thought these very words would apply very well to kind of falling in love or thinking maybe I'm in love, you know. But if you– one always has to be wary about being swept away by one's emotions in these romantic contexts and so forth. On the other hand, if you're too full of doubt, maybe too full of some kind of psychoanalytic theory-- I know when I fell in love, I went and read the books about it and they all say, "Oh no, it's an illusion, and it'll pass in about six months. You think she's perfect now, but she's not." And I didn't think she was perfect. I'm not perfect. Who's looking for perfection? I was in love with her. That was the reality of it. And I knew that there's risk to love of just the kind you were describing for faith in a particular religion or for more or less anything else we do there's a risk. We try to help people. It's one of the challenges of the do-gooder. You try to help people, sometimes you just mess things up. Okay, But it doesn't work to then, well, I'm never going to help anybody because I can't infallibly know if my help will be just what the doctor ordered, you might say. And you're never going to be able to love anybody if you just carry around this kind of corrosive, acidic self-doubt. It can be a self-doubt and skepticism or just even derision. You know, it can take those forms.

Dr. Christopher Denny: [00:33:34] That's, I think, what was at the heart of Michael Buckley's criticism of early modern deism is that the shift to the subject and making subjectivity and individual consciousness the touchstone of how to live life has had the negative impact of really sort of creating a culture of individual monads, and that makes it harder to love. I don't want to sort of personally disparage any of the giants of early modern thought, but I think they bequeathed to the modern West, and even I would say the post-modern West's, this resolute skepticism that can harden in a cynicism that is it is It's not merely corrosion of religion. And I think the critics of religion and what we might call classical liberal critics of religion in the West need to understand this. It's corrosive of community as well. You know, it's not as if the skeptic is going to be able to simply say, "Okay, I reject religious forms of trust. Now I'm going to be able to put my form of trust in secular alternatives, political, technological, economic, etc.." It really is a one way road once you start committing yourself to that idea that you need to be certain above all else. And I think that when you see the sort of the backlash against individualism in the 20th century, you find forms of collectivity that in some ways are the polar opposite of individualism. We need to find ways of thinking about trust that are, I think, less certain that we have a sort of dichotomous choice before us of gullibility versus solipsism. There's a middle ground there.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin: [00:35:43] Yeah. Yeah. Solipsism is not invulnerable either. It's a kind of pretend invulnerability, almost like the child- I'll hold my breath, or you even you can't see me. But that trust is in a way where this began with can I trust the voice? And it can't be blind trust. But you don't get anywhere without some degree of trust and confidence. And if you talk on the interpersonal level and the level of community, one of the most important things in a community, one of its chief assets, is social trust. And some of the countries in greatest trouble are countries in which they either don't have a tradition of social trust, they're wedded to smaller units, they only trust their own family or their own ethnic group or something like that. Their own in-group. And it's very hard for such communities to thrive and prosper because we get way farther trusting each other, even though occasionally we let each other down. But we get way farther that way than with constantly avant garde up and thinking- No, I've got to undercut them to protect my own turf, or my own self-interest, or my little group's interest. That's very undermining for a community.

Dr. Christopher Denny: [00:37:37] Biologically an autoimmune disorder is what happens when the body's defenses turn against itself and autoimmune disorders can be treated through the same sort of medicinal means that we use for bacterial infections and so those disorders can be in fact the most risky and fatal of all bodily ailments. Cynicism is an autoimmune disorder of the psyche, because what it does is when confronted with the sad reality of broken trust, the pat response is well, you know, all people are like that. All people of all societies are flawed. All rulers are in it for themselves. It's all about power. It's all about the lust for riches or fame. And, you know, we're back once again to that spirit of what Augustine called the incurvatus in se- the curvature on oneself that he saw as the mark of the root cause of sin. And it's at that point that, you know, the mind just refuses to intake or be open to the possibility that maybe there is truth out there, that everyone doesn't simply try to cheat or lie or steal or what have you. You know, I’m just the thinker, the early modern thinker, who I've always been most influenced by since college is Pascal because Pascal was capable of being a big skeptic. But he also in the Pensees said, if you look at the world, there's not enough rational evidence to believe, but neither is there enough rational evidence to dismiss. And I thought that's just a really brilliant way to approach the world. And then that's enter the famous wager where Pascal eschews the criterion of rationality as the method by which one will determine God's existence in favor of self-interest, which is another way of saying, how do you want to live? How do you hope to live both in this life and in the next life? I think that's a refreshingly honest rejoinder to the doubters of past and present.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin: [00:40:00] Well, yeah, one of the problems is the doubters focus on this as if it were, the whole question was a proposition that there is a God, God exists, something like that. God exists and told us to X, Y, Z that some religion reports. But we're choosing, as you nicely put it, Chris, we're choosing how to live. We're choosing a way of life. We're choosing a way of life for ourselves and for those close to us, our families, and for our community and our role in our community. We're choosing a whole way of life. And you know, those pursuits, it's hard to quote, refute them, though Plato does a good job. But they just always struck me as little- that's an impoverished life if you're living only for fame. And of course, the people living for fame often discover that when they finally got the fame they've been seeking, it's kind of empty and they find themselves empty. They've done nothing for their own souls, you might say, or their own healthy psyches. And the same just what's the point of endless money? When I grew up with comic books that had a Donald Duck character, Scrooge McDuck. Scrooge McDuck was absolutely absurdly rich, had a whole big warehouse, like a vault in the middle of the city that was multi-story and full of money. And he would just jump in the money and swim around. Well, does that make any sense at all? You know, money is a means. And same with power. People have a quest for power. My early interest was political science because I'm a good analyst of power relations, but power is essentially a means. And so I immediately had to turn to political philosophy because what should the ends be is the crucial question, just to acquire power, just to have power? As though somebody said, "I'm going to get all the electricity in the world and store it in a vast battery." That doesn't-- these things don't make sense. And yet they have some natural impetus in human life.

Dr. Christopher Denny: [00:42:14] I'm reminded of something my high school theology teacher said when asked why he was interested in theology. He said, "I like ultimate things." And at the time, when I was a prep school student, I had become quite a religious skeptic myself. But I was still interested in ultimate things. I just find that I always want to sort of return to that question- why? Why should I pursue this or do that? And it's that that helps sort of ground me in the search for what Aristotle would call happiness. Right? I mean, I like the money, the fame, some of that anyway, would be okay, but not too much of it, but it really is something that I think is critical. What is– To go back to Tillich, what's your ultimate concern? I doubt for most people it's money.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin: [00:43:14] One thing I often tell people, you know, I'm a theist and you're a theist, I take it, so I believe in God. God talked to me and I believe in God and in part just this is my experience. You know, we live in terms of our own life circumstances, experience, what the inputs are, in terms of what we've read and what we've lived through is that of a God speaking to me who is extraordinarily personal. Even though God, I'm told, has these other dimensions beyond the personal. But when I talk to people who don't want to think about God, and I understand that, for a lot of people, God is either intellectually off limits for them, or God is, they have bad associations with the concept of God, maybe bad experiences in childhood. I know I have some that aren't exactly bad experiences, but they're extremely superficial, sentimental understandings that are an obstacle to engaging in that tradition. But I always advise just try to pay attention to the highest level thoughts you have, the highest level desires, the highest level conceptions, the highest level norms. And I'm trusting that, and I do believe, human beings have some capacity for distinguishing between the higher and the lower. And but so don't worry if there's a God or if this is something God commanded, or God wants, or God is watching you if those concepts are non-operable for you. Just live in terms of the highest aspirations you can identify and try to live up to those, try to trust those and try to live up to them.

Dr. Christopher Denny: [00:45:15] I think that's the point at which theists have to be aware that the language of God itself can be problematic, but there are alternatives. I think of someone like Rudolf Otto in the early 20th century is speaking of the mysterium tremendum et fascinans, the fascinating and tremendous mystery. Or Karl Rahner's phrase, holy mystery and the ground of existence to describe God. A lot of people can reject the image of an old guy in a throne, but I don't know anyone, at least any adult, who, when willing to engage seriously in honest conversation, does not recognize that somewhere in life they have encountered mysteries, things that enthrall them, that fascinate them. I don't know what those mysteries are because for each person that's unique. That's where I think the conversation about God is is often most profitably had.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin: [00:46:19]Yes, yes. Yes. It strikes me that other people have deep mystery, too. Mystery isn't just the transcendent or, you know, the divine and or anything in that ilk, but there are amazing depths, and contours, and lights and darks, and ramifications, and I guess depth may be the best word. A kind of mysterious depth to what it is to be a person. And, you know, you try to almost live up to that depth yourself. I was at one conference, a Christian sponsored conference at University of Toronto where some guy started saying he was wondering- what do people mean when these people talk about mystery? And he had a very logical mind. He was a Calvinist and this fit, you know, he had just the right mind if you're going to do these Calvinist deductions. What do people mean by mystery? He just didn't understand it. He said to me, "My wife is a mystery." And yeah, my wife has infinite depths as far as I can tell, and so the women especially, but everyone kind of swooned. "Ah, yes." You know, my wife is a mystery.” But then he went on, "She does things that simply make no sense." And we saw a kind of narrow minded male type of rationalism or pragmatism or something come in, and the swoon immediately dissolved into a, "Oh well, he doesn't even get the import of his own words." Well, he doesn't understand what a mystery is, and I guess some people just don't. And you might be able to put him in a position where he confronted a mystery and came to see- ah, now I get it. Maybe a great piece of art or music or some work of literature where the mystery comes more palpably to his attention. But I'm always struck the more I've done this sort of thing and talk to people that we all have to find which concepts make sense to us, which ones fit our own personal experience, which ones fit our own conceptual scheme. Because we have somewhat different conceptual schemes, we're always trying to improve them and work them out and so forth. But that's a sort of endless life project. At that very conference I was mentioning, there was a young Christian theologian. I asked him, for some reason it seemed appropriate to the kind of talk he'd given, "Why do you believe?" And he said, "It makes sense to the story of my life." And I thought, well, that's a pretty good answer. There, it's not a propositional thing-- I found these arguments to prove that God exists, but I'm living a life and what makes sense of it, brings out the meaning of it? Well he felt this set of Christian commitments did that for someone else it might be a quite different set of understandings or commitments. But in a way, that's what one is looking for- what makes sense of your life?

Dr. Christopher Denny: [00:49:48] For my part, I've always sort of relied upon dramatic metaphors. You know what script makes the most compelling life play or life story? And so I think that the quest for meaning, and for some of us, the quest for beauty and truth, to give the philosophers their due and goodness are, you know, criteria that impact a huge number of people's decisions about what they are convinced is ultimate and what isn't. And I think the mystery of life is that we have so many simultaneously, like a multiplex theater, so many simultaneous productions going on at once, and people sort of move in and out of each other's plays. And that's a sort of beautiful kaleidoscope.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin: [00:50:44] Yeah. And that's one of the, I think, leading messages of God: An Autobiography, because I'm kind of taking– God gives me a tour of these different traditions, starting with prehistoric people and going around the world. And basically, it's the God who talks to me saying what God was trying to achieve with those people. And sometimes what they got right and what they got wrong. But in every case, there was something that was coming through that was from God, and the conclusion that comes out is, well, God has these many aspects. And so He gave different cultures, different sides of God's Self or found them, Sometimes it's an interaction, found that they were responding to some aspect of the Divine Self. And He almost discovers the Chinese picked up on the a kind of cosmic harmony. Oh! God says, "I kind of discovered, well, yeah, I am kind of cosmic harmony," you know. And we all have that kind of experience, and this very anthropomorphic version that I'm given, God is discovering. Okay, Yeah, that's good that they picked up on that. You know, that is another side of God's Self. And then, of course, that was a motivation for Theology Without Walls, which toward the end of the book, I'm told to start. But it had to do with kind of figuring out what's the story with how do you figure out a story or tell a story? You know, you don't know if one wants elaborate, rational structure of a kind of systematic theology or whether one wants a kind of coherent set of stories, and kind of see their interrelation between them. A lot of life in a community is how the story is going to go. You look at any good dramas where there's a whole community and you appreciate the variety of characters, their strengths and weaknesses. They're all adding to the story, even though they're living out their different aspects of it. And thats– you talk about dramatic metaphors. I mean, that's a kind of dramatic metaphor for what life is really like. And a lot of your task and mine, Chris, is to- okay, in this melange, or whatever you call it, of stories of people living our lives looking for meaning, truth, beauty, goodness, trying to instantiate those, trying to embody them and act on them. What is your role? What is my role? And then you don't have the role of trying to be the total. Your role is to figure out, okay. And I often think of an orchestra. Maybe your job is to play the flute. To play the flute you have got to stick to the flute playing role- or the tuba, I often think of because it would be very bad if the tuba player tried to take over the whole thing or dominate. But the tuba has an important role and so does the flute and so forth. So we all play our own instruments in this kind of ongoing drama of our lives together, in our lives in tandem with whatever is ultimate however you want to conceive that.

Dr. Christopher Denny: [00:54:12] I love the metaphor.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin: [00:54:13] Yeah. Yeah. Well, that might be a good place to end, Chris, because that's a good lesson for us all, because I think the dramatic metaphor is actually quite powerful. Well, thank you again very, very much.

Dr. Christopher Denny: [00:54:28] Thank you for having me.

Scott Langdon: [00:54:40] Thank you for listening to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. Subscribe for free today wherever you listen to your podcasts and hear a new episode every week. You can hear the complete dramatic adaptation of God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin by beginning with episode one of our podcast and listening through its conclusion with Episode 44. You can read the original true story in the book from which this podcast is adapted, God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher, available now at amazon.com, and always at godanautobiography.com. Pick up your own copy today. If you have any questions about this or any other episode, please email us at questions@godanautobiography.com, and experience the world from God's perspective as it was told to a philosopher. This is Scott Langdon. I'll see you next time.