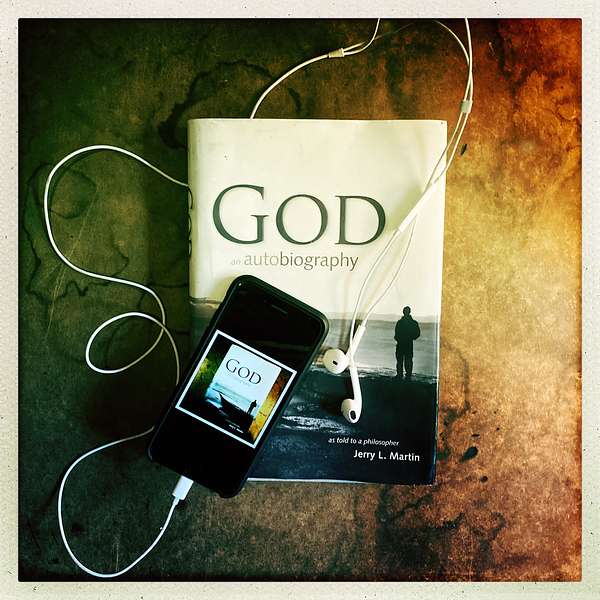

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

124. The Life Wisdom Project | The Afterlife And Reincarnation | Special Guest: Dr. Jeffery D. Long

As a child, Jeffery questions his Catholic upbringing in the wake of a tragic accident. Young Jeffery, looking for comic books at a flea market, providentially finds the Bhagavad Gita. Opening this book from the other side of the world, he finds what feels like "an artifact from home."

Continuing a life-long journey with Hinduism and Buddhism, today, Dr. Jeffery D. Long is Professor of Religion, Philosophy, and Asian Studies at Elizabethtown College, is co-founder of Theology Without Walls, and an author.

In this The Life Wisdom Project episode Jerry and Jeffery share a conversation that travels everywhere a Seeker hopes. From Star Wars to philosophy, the afterlife, Karma, reincarnation, and past life regressions. Exploring life patterns and the work and the learning involved in this life.

How does one recognize in this life what the rightful challenges are?

FIND THE SITES- Dr. Jeffery Long | Theology Without Walls | What is God: An Autobiography

BUY THE BOOKS- Hinduism in America: A Convergence of Worlds | God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher | Theology Without Walls: The Transreligious Imperative

LISTEN TO RELEVANT EPISODES- [Dramatic Adaptation] I Ask God About Life After Death

God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher, is written by Dr. Jerry L. Martin, an agnostic philosopher who heard the voice of God and recorded their conversations.

The podcast began with the Dramatic Adaptation of the book and now has several series:

- Life Wisdom Project-How to live a wiser, happier, and more meaningful life with special guests.

- From God To Jerry To You- a brand-new series calling for the attention of spiritual seekers everywhere, featuring breakthroughs, pathways, and illuminations.

- Two Philosophers Wrestle With God- sit in on a dialogue between philosophers about God and the questions we all have.

- What's On Our Mind- Connect the dots with Jerry and Scott over the most recent series episodes

- What's On Your Mind- What are

Share Your Story | Site | Facebook | Instagram | Twitter | YouTube

Scott Langdon [00:00:17] This is God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. A dramatic adaptation and continuing discussion of the book God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin. He was a lifelong agnostic, but one day he had an occasion to pray. To his vast surprise, God answered- in words. Being a philosopher, he had a lot of questions, and God had a lot to tell him. Episode 124.

Scott Langdon [00:01:06] Hello and welcome to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. I'm your host, Scott Langdon. And today we return to our series The Life Wisdom Project. In this, our sixth edition of this series, Jerry talks with Dr. Jeffery Long about his thoughts and reflections on episode six of our podcast called I Ask God About Life After Death. Jeffery's personal story, combined with his lifetime of study on this subject, makes for a terrific conversation, And I'm so glad you're here for it. Remember, you can always find the complete audio adaptation of God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher for free anytime by beginning with episode one of this podcast and listening through episode 44. Here now is Jerry's conversation with Dr. Jeffery Long in our series The Life Wisdom Project. We begin with Jerry speaking first. I hope you enjoy the episode.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:02:08] Well, I'm very pleased to have Dr. Jeffery Long as my colleague in today's discussion of life wisdom contained in this particular episode. When I spoke to Jeffery, I told him that I thought this episode had his name on it, and I think that will come clear why I said that. When I first joined the American Academy of Religion, because I didn't know much about religion, so I thought, this is a great place to learn, this is where all of those scholars gather. And since I didn't know anybody, I would go to various panels and then invite the smartest person on the panel to have coffee. And Jeffery Long was one of those. And we did have a meeting in Chicago over coffee. And I told him my story. He told me his and our friendship went on from there and our colleagueship went up from there. He's one of the co-founders of Theology Without Walls. He's now a distinguished professor of religion, philosophy and Asian studies at Elizabethtown College, a very fine liberal arts college in Pennsylvania, and the only person I know who's an American born Hindu. He was a serious Catholic and now a serious Hindu. And he brings a lot from both traditions to bear on his life and thought. And as you hear his story, part of the life wisdom is just to see how a very thoughtful young person, just as a kid, deals with family tragedy and with his own theological search for meaning.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:03:57] Well, thank you for being here Jeffery Long, very glad to have you in this episode. And as you understand, I just felt it had your name on it. And that will become clear, I think, in the course of the discussion.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:04:10] Thank you.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:04:11] Something I was told somewhere in the God book, though not in this chapter is that the afterlife is about the meaning of this life. And, you know, I've always kind of puzzled over that, that doesn't look like what it's about.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:04:28] Right. Right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:04:29] But anyway, let's just let that thought hang in the air a bit, because I think an example might be your own story, if you don't mind, though you've told it many times, but I find it so deeply moving and, you know, instructive- is your father's tragic death.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:04:50] Yes.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:04:51] And then you're encountering a book at a flea market sale one day.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:04:56] Yes.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:04:56] Just tell us about that.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:05:00] Sure. Sure. Thank you for the invitation. And this topic is something that's very dear to me. And so a little bit of my background, I grew up in a small town in Missouri. I was raised in the Catholic tradition, though I have to say, my family was not terribly orthodox. We were-- everyone was very independent minded and I was never prevented from inquiring and taking an interest in theology and philosophy and pursuing my own interests. So that's a little bit of our, my family background. My immediate family was very small, just my mother, my father and myself. And the extended family, though, was quite large. Cousins, aunts and uncles, grandparents and so on. My father worked on the railroad and he was a railroad engineer. When I was ten years old, he was out with a group of friends and they were drinking and, you know, not being very responsible. And he was a young man at the time. I mean, from my current perspective, I'm now 54. I should say this body is 54. He was only 30, about to turn 31 at the time. So he was quite young. He was in an accident which left him paralyzed, most of his body from the basically the shoulders on down. And this was really quite devastating for him and for the whole family. He was always a very physically active person. He was a very gifted musician. He enjoyed playing the guitar and singing. He could no longer do that. He didn't have the lung capacity to sing, and he obviously couldn't play an instrument. But before he was injured, he could play just about any musical instrument. A great sense of humor, liked to make people laugh. So was sort of a natural entertainer. He worked on the railroad, he was also very much into carpentry, so that was his hobby besides music. And so also something where you work with your hands a lot. So he was deprived of everything he really enjoyed a lot in life by this accident. He was in a lot of physical pain. A lot of times people assumed that with paralysis you simply can't feel anything. But he had sort of phantom limb experiences, and so he was in a lot of physical pain much of the time and a great deal of psychological pain. He had been in the U.S. Army, he had been in Vietnam, and so he was a veteran. So through the Veterans Administration, we were able to get some equipment that helped make his life a little easier. And among these things was a wheelchair that he could control with his mouth. And this gave him some independence. He could go not just around the house, but he could go outdoors. He could sort of travel around town. We accompanied him in the beginning, and then he got very angry. He wanted to have his independence. So, you know, we said, okay, I mean, what my mother and I, what else could we do? And he was really very, very insistent on it. But we don't know this, but I think it's probably fair to say that he took his own life. He ended up placing his wheelchair in the path of an oncoming train. He knew all the train timings because he worked on the railroad. So it was officially ruled an accident. But in our small town where everybody talked about everyone and knew everyone's business, the general sense was that he had chosen to end his life.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:08:37] And what other options did he have? You know, well, there are no good choices for him.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:08:44] There are not many good choices at that time. And it was in the early 1980s. A lot of people listening might be familiar with Christopher Reeve, who played Superman, had a very similar accident, but at a later time. And he, of course, he had access to the absolute best medical care as an actor and so on. But he was able to-- Christopher Reeve was able to do some things in his life that I think weren't available to my father at the time. What looked most likely was either he would spend the rest of his days at home with us. My mother was taking care of him. She went on and became a nurse after this because she got so much experience with health care, working with him. And she found it gratifying to help people in that way. So she went and became a nurse for the next 25 years till she retired. And then his other option would have been to go into a nursing home, which he talked about that because he didn't like being a burden on my mother. But then we didn't even want to think of, you know, making him go stay somewhere else, right. We wanted him to be-- we thought he would be as happy as possible at home, but he wanted to free himself. And in terms of our topic of the afterlife, this whole experience really made me, almost obsessed with this topic. And it remains a very central one for me today. You know what happened to my father? I believed at the time, and I still believe that we are not identical with this physical body. And his experience with the paralysis really taught me that. Because if the body can become a prison, then what is it imprisoning. Right? It is this other entity that is keeping you from doing what you want to do. I've lost other loved ones since then to cancer. What is cancer but the body turning on itself, right? So if the body can turn on itself, become its own enemy, if it can become our enemy, then it's something distinct from us, right? It's something separate.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:10:57] This is itself a very important insight, Jeffery. You know, as we and people increasingly think we're our brains, I hear it that way, you know, it's our brain thinking. I don't believe that. I think of it as an instrument, the way the writer is an instrument and the radio is an instrument.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:11:16] That's right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:11:17] But it's natural in our scientific age, and neurology, of course, does so many things. But it's very important for people to realize, because it's number one, that you're not your body and therefore there's more to you and there's a kind of freedom of soul in there being more to you.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:11:35] Yes.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:11:37] Then just what the body that, as you put it, can become a prison.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:11:41] Right. Exactly. And that was definitely my father's experience. And so and this isn't an argument that would probably convince skeptics because they might say, well, that's just very poetic. You know, you're thinking of the body as analogous to a prison. But for me, it was very persuasive that I just I saw that everything he had been- his sense of humor, that spirit that came through when he was playing his music is not reducible to this, basically, this piece of meat, which is what his body became because of his accident. Now it's an important instrument, I think. I don't agree with anyone who would want to downplay the importance of the body. Like, you just mentioned a radio. I think a radio or television is a good comparison with the brain and the-- we needed to tune into this realm where the real us is residing and have experiences in this, you know. We can call it virtual reality, I suppose. We need this equipment in order to interact in this sphere, but we are not that. And if we are not that, that means that when this ceases to function, then what we really are must in some sense go somewhere, be somewhere having some kind of experience. And I believe that he freed himself when he placed his body in the path of the train. I think he, his soul became free. I think he had escaped from that prison. I think he was thinking about himself. And I think that's quite understandable in his situation. But I think he was also thinking about my mother and it was very physically and mentally trying upon her what was being-- I mean, she had to get up all hours of the night and take care of him. It was basically a 24 hour job. And after he passed away, I think it was partly due to depression, but also partly just exhaustion, she slept for several months after that. It was just so much that we had to deal with. So I started thinking a lot about the afterlife. You know, he was free, but where did he go? What did he do? And I remember the people who informed us first that he had died were my grandparents, not his parents, but my mother's parents. The, my-- I told you the extended family was large. So my aunt was at the laundromat downtown when the accident happened, when the train hit. And she didn't see it happen, but she was very nearby where it happened. People immediately crowded around and so she immediately contacted my grandparents, said you'd better tell them before the police do, or they hear it from some random person. So it was good that we heard it from my grandparents. And I remember my grandmother saying, "Your dad's in heaven with Jesus now," she said. And I remember feeling that-- I mean, the loving sentiment she was communicating there I felt very deeply and very clear-- but I just remember thinking, is he there yet? Because I had this idea that you had to reach a certain level of perfection to reach that abode. And growing up at in the Catholic tradition--

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:15:11] You were a rather serious Catholic, though not--?

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:15:13] I was a very serious Catholic. And I was thinking, "Well, he is probably in purgatory." And even though he'd been through so much, I've sometimes made the comment to people, you know, he'd been through hell already. He-- I loved him more than words can say. He was not a perfect human being. There were times that he could be quite cruel, quite selfish, and I just thought he probably needed to pass through some levels of something on his way to that realm. But I took what my grandmother said to heart, and it comforted me. But I thought, well, he's probably on his way there. You know, that was my instinctive thought in the middle of this grief. The idea of hell or eternal torment- I have to say, I never really accepted that because whenever my parents would punish me for something, they always said, "This is to teach you so that you'll do better next time," right? So you don't make the same mistake. And an eternal punishment by definition, cannot improve you. You just keep getting punished again and again and again. And I thought, well, if my parents love me and are kind and fair, how much more kind or fair will God be? How could the imperfections of one finite lifetime lead to eternal punishment? I just thought that seemed like a very cruel idea. And a lot of people in the Missouri where I was growing up believed in that. And in fact, I remember being told I was going to hell by people who were Evangelical Christians. They didn't like Catholics. And then when they found out I was, you know, as your listeners will soon hear, sort of a weird Catholic who is dabbling in Hinduism and Buddhism, then they knew I was going to hell, right? They just were sure. But it seemed to me like a God who would knowingly create imperfect beings and then punish them forever, which sounds very cruel, does not sound like the God I believe in or the God that it's taught in the New Testament. So I didn't believe in hell, but I believed that there were hellish states. Hellish experiences that we might have because there were people who had done great harm and great evil through history. You think about the great dictators and, you know, the people who've been very monstrous and cruel through history and then even all of us with our, you know, little pettiness and selfishness and so on. We're not perfect yet. So I sort of had this idea that purgatory probably is where most of us end up, and then eventually a heavenly state. But, you know, that started to bother me too, because I started thinking, if we still have so much work to do (and quick side note, work is a great translation of the term Karma, which I would learn many, many years later, but if we still have so much work to do), what were we doing here? What was the point of this life? So I started thinking, maybe we're already in purgatory and maybe we just keep coming back until we get it all right, get it figured out, and then we're ready to graduate. Right? I was a student, and I've been a student all my life. I'm now a professor. I think, in terms of progress through school. Right? So that we in a given lifetime, we have lessons to learn. We have work to do, and then we just keep on going till we finish our work. And so I was thinking in terms of something like the idea of Karma and rebirth before I had become aware of non-Western religious traditions. But it wasn't long before I started becoming aware of those traditions. My father had a big music collection. He again, he loved music, so he loved playing music himself but he also loved listening to music. And any older listeners will remember 8-track tapes and, you know, vinyl LPs and so on. So my father had all these things and a group, one group he liked, he wasn't a huge fan of them, but he liked the Beatles. Well, I love the Beatles. I became sort of hooked on their music. And, you know, George Harrison, especially from the Beatles, took a great interest in India. All of the Beatles went to India in 68. They studied meditation in Rishikesh with Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. This intrigued me greatly. I was like- Oh, what were they doing in India? Oh, that's very interesting. And it sounds very spiritual and cool. And then I saw the film Gandhi when it came out. I was 13 when that came out. So my mind was just filled with like this film Gandhi, which really made a huge impression on me. You'll hear someone who fought evil, but he didn't use a phaser or a lightsaber, right? I'm always into science fiction and Star Trek and Star Wars, but God to use the power of truth. And so I started learning whatever I could about Gandhi. I started reading, you know, learning more about the Beatles and George Harrison, especially listening to their music, interpreting their song lyrics. And then I read this book that I think a lot of seekers have read Fritjof Capra's The Tao of Physics on Science and Religion. And I always had an interest in science too, especially astronomy. It's kind of an extension of my science fiction interest. And in all of these sources in some of George Harrison's album cover art, in the books that I found on Gandhi, and then in Capra's Tao of Physics, they all mention this book called The Bhagavad Gita, and I started thinking, "This seems like a really profound book." They're all referring back to this. This seems to be the source that everything comes from. And one day, by this time I was around 14 years old, I went to a local flea market in the parking lot of the Methodist church, and my grandmother was there. She used to sell a lot of antiques and artwork and that sort of thing, and then buy other people's stuff as well. And I would often go to these both to help her, and also I would find old comic books and science fiction paperbacks and all kinds of treasures in these flea markets and garage sales. So I went to the garage sale or went to the flea market, rather not particularly thinking about the Bhagavad Gita, but during this period the book was very much in my mind as something I wanted to read. But I went to the flea market thinking, oh, I'd find some comic books or something. So I saw a table covered with books and magazines. So I headed straight for that. And right on top was the Bhagavad Gita. It was the translation, the Hare Krishna translation. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. I read his name and I thought, "Oh my gosh, this sounds like something from Star Wars," right? That just it was so interesting and different from anything I was accustomed to. And I opened the book. And there was an illustration of a man who had recently died and his body was surrounded by his mourning family. And nearby was a monk sort of serenely witnessing this scene with compassion, but also with detachment. And there was a verse at the bottom said, the wise lament neither the living nor the dead. And boy, this really hit me because that family with the mourning over the man who had passed on reminded me so much of my father.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:22:26] That was your family.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:22:27] It was us, right? We were there. And here is this wise sage saying "Don't lament." So I said, "Okay, well, what's up with this?" So then I looked up the page number and it was from the second chapter of the Gita in which Krishna is explaining to Arjuna that death is not the end, that just as we cast off old and worn out clothing and put on a new set of clothes, the soul casts off the body and takes on a new one and says the wise are not deluded by these changes. And it really hit home because this was precisely the way I had been thinking about the afterlife. And here it was in this book from the other side of the world. And I finally, a few years ago, found the words to describe what I felt that day, and thinking about Christopher Reeve again, if you think back to the first Superman film that he was in, you know, there's that scene where he finds a crystal from his home planet of Krypton and that guides him to his Fortress of Solitude and so on. Finding the Gita for me was like being an extraterrestrial raised by humans on Earth, and then finding an artifact from my home planet.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:23:43] Wonderful!

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:23:43] It was like- this makes sense. This makes sense. And then I looked at all the pictures, the illustrations of Krishna and, you know, all of the various lessons from the Gita are illustrated, you know, very colorfully and vividly in the book. And to me, it was just like, "Oh, this is this is it. This is a voice from home."

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:24:48] This is a wonderful, you might say, example, exemplar, you know, perfect lesson of recognizing that here is a truth for me.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:25:01] Yes.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:25:01] It's something you know, I've had the experience of talking to a woman who heard me speak at AAR, early on, maybe the first time I ever spoke, invited me to speak in Philadelphia to an Institute for Advanced Buddhist Studies. And we first went to have lunch and they just hired a woman who is a Jewish psychotherapist-- and her story was it had started to rain on her when she was in downtown and to get out of the rain, she went into the nearest building. It was there downtown, bigger building of the Wuhan Institute for Advanced Buddhist Studies. And as soon as she went in, she felt the way Superman felt, you know, and the way you felt, "Oh, somehow this is my place."

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:25:50] Yes. Yes.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:25:51] And I think people take-- you have to take-- these moments very seriously. And I believe that sometimes, you have described this as providential.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:26:00] Yes.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:26:00] It's a difficult concept, but you would need to recognize providential things as providential. Not everything is random.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:26:10] That's right. Not everything is random. And, again, you know, a skeptic could tell maybe a very persuasive story about why all of this happened. But in terms of its relevance to my current life-- that's my origin story. Right? That finding the Gita after my father's passing that is how I got-- felt drawn to Hinduism, that's how I felt drawn to studying the world's religions and philosophies. And that's why I'm a professor and writer of these things today, because it all stemmed from that experience--.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:26:45] From that moment.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:26:45] Yeah, from that moment, and then the desire to just immerse myself in all this and also to share it with people, not in a proselytizing sense. And I've had people ask me before, "Well do you think I should believe in rebirth?" You know, about themselves. I say, "Oh, believe whatever you want, but this is how I understand it." This is my framework that makes sense to me. But, you know, everyone needs to figure these things out for themselves. And of course, there's a lot of suffering that's been created in the world by our attempts to make everyone fit into our mold, whatever it is.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:27:16] Yeah, no, it's just best-- you do it exactly right, Jeffery. It's best just to tell people, "Here's what I believe and here's why I believe it." And then you take that as data, you know, put it through your own system.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:27:29] Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:27:30] As you know from this episode, on, you might say, afterlife, I have no interest-- a completely different story. No -- afterlife. I think if I do come back as Wong Hang, what do I care about one Wong Hang? It's a completely different person and something completely different world or period of history and no similarities between us. And I had to quiz God a lot about that. Well, your soul is the same. The same soul.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:28:02] Right, right. Some personality traits, those you know in the Hindu tradition, samskaras, those get passed on.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:28:10] Yeah. And then I, you know, I had that dream where that ended up in a kind of state in heaven, though it was interesting, I only didn't make much of it at the time, but it was with Hindu nuns.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:28:24] That's interesting.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:28:25] Was the leader of that order. Is that something?

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:28:28] That is something.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:28:28] That was also my wife, Abigail, but from a different life.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:28:32] Yes. From the ancient Israel, you said?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:28:35] Yeah, from ancient Israel.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:28:37] Yes.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:28:38] And I thought, you know, I just had the sense, it was a very vivid dream and a long dream, you know, well, it's over now. This is the end of the dream, because I had gotten to heaven and had this experience. And then I was surprised. No, the dream went on. But now it seems what I see is a child waking up in a basket in what might have been a rice paddy or something like that.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:29:08] Right, I know.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:29:08] And, you know, the child being, you know, a different person and yet having retained, oh, some kindness or something from the experiences I'd been through, some-- I had acquired something. A bit of wisdom or personality or something that did carry over. And I didn't have a doctrine. You know, you're talking about a tradition that has studied that and developed, I'm sure, more than one account--

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:29:38] Right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:29:38] Of exactly what happens. But I didn't have any of that. But I just have that sense. And then when I prayed about it- Yes. Reincarnation, the version I'm told, is a little different from the Hindu versions I've heard of. Though, I would suspect there's some Hindu version that would be quite similar to what I received in prayer.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:29:58] Well, there is-- what I read in your book I find this very close to my own understanding, my personal understanding of Hinduism. Of course, when we say Hinduism, we're talking about a lot of different traditions, a lot of different texts and so on. But the idea that there is a kind of, if you want to call it a heavenly realm, that is almost like a waystation between these lives. And when we're in that state, you describe looking at the world much in the way that God looks at the world and that in the following chapter it says very beautifully, you know, that at bottom the soul and God aren't divergent. They're distinct, but they're not divergent.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:30:39] They are at one. At one in perfect harmony.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:30:43] Yeah. And that to me, sounds like what-- that sounds like the meaning of Advaita, nonduality. Which as who I think you know probably pretty well Anant Rambachan has said that it doesn't mean one in the sense of obliterating difference, but it means always together. That they're not-- they are at one, I think it's a nice way of putting it. And then we return on my understanding, because we still have work to do and in fact, we choose to do that. I remember being very moved later on in college, I had already sort of fully adopted the idea of rebirth from Hinduism. But when I read Plato's account in the Republic, that also rang true that there's an element of choice and that the way Karma works, I think it's sometimes seen as a kind of mechanistic thing. You could see it that way. I think there are aspects of it that are like that, but when we are in that state where we have a full comprehension of what we need to know and do, we desire that. And so it's not simply that we are sort of forced to say, you know, be reborn in some particular condition. We say, "Okay, no, this is what I need to do." We feel drawn to it.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:32:12] In some sense. The soul knows what it needs.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:32:17] Right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:32:17] And again and God: An Autobiography, it isn't so much of purgatorial assent, you know, toward perfection.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:32:25] Right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:32:25] It's that there are many aspects to the divine reality. There are many lives to actualized aspects of that, including lives that go-- that have very different difficult challenges.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:32:37] Yes.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:32:38] And there's something you learn. There's something your father learned from that, an extraordinarily difficult life.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:32:45] Yes.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:32:46] That he would not have learned in any other way. Right?

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:32:48] That's right. That's right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:32:50] That some, you know, might say, hopefully we'll never learn.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:32:53] Right. Or maybe we already have.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:32:56] Somehow in another life we've been there, done that, and or learned whatever one learns from that experience. But each life is a whole, you might say, new world, and it's one in which there are many more things for you to be living and ways to improve, and you might say sins to encounter, failings to encounter and grapple with. And so anyway, it's something like that. It's a huge ongoing drama.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:33:28] Right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:33:29] Of life with the Divine.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:33:31] Yes.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:33:31] And if we go back to that opening thought I was suggesting that the afterlife has to do with the meaning of this life as I was sometime was told at some point. How would you apply that? You know, in the kinds of things we're talking about.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:33:49] Right. So it's quite understandable to be-- once we have this idea of multiple lifetimes, it's quite understandable to be curious about who was I and where was I and what was I doing in the 15th century? Or, you know, I come to some place. My wife and I visited Italy this past summer, which we just both loved, and there's certain places I felt very drawn to then, okay, have I been here before and so on? That curiosity is understandable. But what I have also been taught and learned and heard and felt through the years is that if it's only curiosity, there's something sort of unhealthy about that, that it becomes a preoccupation with self, right? Self of not the higher kind, but the sort of lesser self, the ego.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:34:45] A kind of greed, you know, curiosity as a form of cognitive greed.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:34:49] Yeah, exactly.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:34:50] I want to know this. I want to know that. I want to--.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:34:51] I want to know it all.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:34:53] And then I want to be the Sherlock Holmes of the universe.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:34:58] Of the universe. And we've forgotten those things for a reason, right? So it's like, yeah, well, we're sort of almost trying to defy that in a way. So what I've been taught and heard and felt is that we should explore past lives solely for the purpose of learning lessons that apply to the present. Right? That again, if you go back to the idea of Karma that we all have work to do, and I have almost I tried to eliminate from my mind the idea of good and bad Karma. I think we have easy and difficult work. I think my father had some very difficult work. Then, you know, at different times we have the work that we enjoy and then we have work that is drudgery. But that's very subjective in a sense, though, some experiences seem to be inherently painful and difficult, but we have them because there's some learning involved. Now, if again, if we're accepting this whole model of reality that suggests that we're back here again because there's something that we didn't finish before and that we are continuing that process. So there may be situations where learning about something that you did before may be very illuminating to the present life. And so delving into it with that intention in mind, I think it can be a good thing. And I've had the experience before-- there are various methods of learning about past lives, and I've had a couple of experiences that were very positive where I learned things and found those lessons helpful to what I was experiencing in the present. I also had the experience once of being very sternly warned not to explore purely for the purpose of curiosity. And so, in fact, I could share that story because I find it amusing. In the present life, the present state, back when I was in college, I read a book on past life regression. The book very clearly said, "Don't try to do this by yourself." So I tried to do it by myself.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:37:08] Yes, of course.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:37:10] And it worked. But this is where I got my stern warning. And I think that what I received was an actual memory, but it was a memory that was chosen for the purpose of saying, don't do this anymore. Because I went through the regression and I sort of counted backwards. I did everything that the book said to do. I was lying in a bed, in a dorm room in college, and it was afternoon. I didn't have a roommate. It was during summer school. I didn't have a roommate. And so it was afternoon. No one was around. No one would disturb me. So I said, "Okay, I'm going to find out about a past life." And I did the regression and suddenly I'm standing in knee deep water in a creek, in a forest. Very beautiful scene, there are trees, and there's a lot of bushes and sort of shrubbery nearby, a very wild environment. And I'm wearing animal skins, so it looks like past life from maybe, you know, very early in the history of humanity, you know, what we would vernacularly call the caveman era. And the stream of water is going over my feet. I can feel it up my feet, my lower legs. I'm looking around at the bushes and suddenly a massive grizzly bear lunges out from the bushes in front of me and roars. And in this life, I opened my eyes. I sat straight up in the bed and my heart's racing. I said, "Okay, I'm not going to try that again."

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:38:41] Right. That's a wonderful story.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:38:44] And I suspect it was a genuine memory. I probably got eaten by a bear in, you know, some time before the last ice age.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:38:50] Yeah. Yeah.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:38:52] That was very nicely chosen by either my, you know, whatever spiritual guides or my own higher self to say, "Here's what you get if you do this on your own."

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:39:02] Yeah.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:39:03] So. I didn't try it anymore.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:39:05] Well, without past life regressions, and even if one brackets, sets aside, you know, a belief in reincarnation or whatever, how does one recognize in this life what your rightful challenges are? Which, you know, I said this episode had your name on it.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:39:27] Right. Right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:39:28] Which task or challenges have your name on it? How do you recognize that you have any--?

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:39:35] Well, I feel I've gotten some more wisdom about that in this life. And some of it has been also from observing students. You know, I work with young people, the college students, a lot. And what I consistently find is that with very rare exceptions, the past is the best guide to the future. That we do change but at a glacial pace for the most part. Again, there are rare exceptions. There are people who make dramatic changes in their lives and you can't believe it's the same person that you saw, you know before, you know. But for the most part, we shape a trajectory based on our past choices. We continue to make similar choices. And if we think of the past as extending even beyond this life, then you can see that there as well that we might be repeating patterns in this life that we've had before. And what we find and again, you can even bracket the whole concept of reincarnation and just look within this life and say, what are the patterns you are repeating? And do they make you happy?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:40:46] Yes.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:40:47] And how do they affect the other people around you? And if you start to find that those patterns are causing unhappiness, then that's an invitation to change and to experiment and to try something different and to keep an open mind about the future. And if we find that there are certain patterns that consistently lead to happiness for ourselves and others, then we'll keep repeating those, right. The universe has this wonderful way of rewarding, you know, right behavior. And I don't mean short term happiness. The Bhagavad Gita has this great expression, it says "There are those--" or it says, "Beware the poison that initially tastes like honey and go toward the honey that initially tastes like poison."

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:41:39] Yes.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:41:39] You know, meaning some things may seem very pleasing, but they ultimately lead to unhappiness. And we see that, you can see this with addiction and so on. But then there's some things that seem unpleasant in the beginning. Oh, you mean I'm going to have to change my routine, I'm going to have to actually learn something and do some work? Darn it. But it ends up being very rewarding in the long run. So it's taking those paths and pursuing them that I think transforms us in a positive way so that we can use the past and our past experiences as a way to guide us in the future. There's a cautionary note about that, though, as well. I am the type of person who I sometimes will compare myself to a cat. If you have a dog who's absolutely devoted to you, you can get angry at that dog. You could spank that dog. You can, you know, I've seen you know, I don't do it myself, but I've seen people, you know, hit their dogs and so-- and the dog will still love you and still come back to you. A cat if you do that, they'll run away and they'll never come back.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:42:47] Yes, yes.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:42:48] I'm a little like that. If I feel I've been hurt, If I feel I've been wronged, I will withdraw and not reengage. And it's hard to pull me back in, even impossible. In some ways, I think this is wise because it can protect you from people who are genuinely harmful. One of the things I've been learning in my life is how to avoid people who are-- who really don't have the best interests of others in mind, but they want to, you know, exploit them in various ways. And I've been learning to discern that.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:43:21] Some books describe them as people who are toxic.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:43:25] Toxic. Right. And I get nervous about that, too, because I think we could probably all be toxic. And so I don't want to be overly judgmental, but if I encounter someone who I experience as like that is like, okay, I'm this is not a person I want to spend my time with, right? I know that one needs to be careful about that instinct because it could be that the moment you feel uncomfortable, you just withdraw from people, and I've done that many times in my lifetime. And one of the things I'm learning to overcome is that tendency to develop the discernment. To know when it's appropriate to withdraw and when it's better to stick around and realize, well, maybe that person's just having a bad day and maybe you could really do something to help them, and maybe they might end up being a very dear friend in the long run. So.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:44:17] Yes, And it can also be, you know, a lot of-- we don't want to just get along all the time.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:44:24] Right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:44:25] What we do for each other is challenge one another.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:44:27] Exactly.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:44:28] The person who even points out, hey, you're doing the wrong thing here and it may be a wrong thing that you're attached to in some way. Well, and that makes you very uncomfortable. So you could blame them for not appreciating you or not understanding you or something, or for being closed minded because they don't see the world the way you see the world. So that's one of the things we owe to each other.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:44:53] Yes.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:44:53] Is to without being judgmental, I often say making judgments is what life is all about, but being judgmental where to put yourself above the other people.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:45:06] I like that.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:45:07] Then, you know, exercise in the end, power over them, but inflate your own ego at their expense.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:45:15] I really like the way you're putting that, Jerry. And I think that the particular period of history we're living through right now, which is characterized by strong, strong polarization, is the lesson for many of us souls who have chosen to be alive at this time is to learn how not to be judgmental. And like you said, yes to judge, to judge right and wrong, I should do this, I shouldn't do that. But not to then look at another person and say, "Okay, you're a bad person and you're irredeemable and I don't want anything to do with you, and I'm going to oppose you in every way that I can." And behind every person that I find that is hurtful or cruel or selfish or whatever it may be, there's some pain there that has led to that. And that doesn't mean we should let ourselves be the victims of that person's bad behavior. But it means that we can say, okay, they have a role to play in the universe, too. I'm not just going to rule them out the way we're often, I think, tempted to do. We just sort of lump entire groups of people as being beyond the pale, and then we're missing out on whatever they have to offer us. And we're missing out on the ability for us to offer something to them.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:46:39] Yeah. Our first step in these difficult cases, some interesting book called Difficult Conversations, that's helpful. Is to start off, not just, oh, I see the world this way, the other person sees the world or this little part of it that we're contesting over a different way. But why do I see it the way I see it? Have some self reflectiveness about that. And why is this other person seeing it differently? And maybe in a way that I just find difficult to comprehend that seems perverse or malevolent. But you need to figure out why. And it may be perverse or malevolent, but you want to find that out, not just assume it. Not everybody is Adolf Hitler.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:47:30] Exactly.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:47:31] You know, so you can't assume that someone who seems at the polar opposite in some respect or other from me is necessarily evil on two legs.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:47:43] Precisely.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:47:44] They have a complex story of their own.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:47:47] This is the challenge I think we're all facing now, is to see that goodness, that divinity, that inner positivity even in people that we find very, very problematic. And again, it doesn't mean being naive. It doesn't mean surrendering ourselves to those people at all, but it means not joining in the polarization game. You know, "I'm going to hate that group now, and my whole identity is going to be based on being not that." I see that happening a lot.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:48:22] Yes, that's very unfortunate. And it's hard to get past once you're in that mode and especially if you're in it, you know, collectively, you know, you pull your friends into the same attachments of attitude.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:48:37] Exactly.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:48:38] It's very, very hard to get past it, but one has to in those cases, in part with the group think challenges, it's to maintain one's own independence of thought and feeling. You know, you may not be able to feel for this other person, but maybe I can.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:48:56] Yes.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:48:56] Or maybe I've known somebody in my life or a relative or something has been very much like that. And I can use that connection to help understand this person that we're encountering. They're probably feeling something similar to my relative or something.

Dr. Jeffery Long [00:49:12] And this ties in nicely with our past life discussion because, you know, the Buddha once said we should revere every being we meet because we've all been reborn so many times, every being we meet was one of our parents at some point. So you have to respect that, whereas, you know, in traditional Asian society, you know that you have for your parents, he's saying extend that to everyone, to all beings.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:49:40] Yes. Well, that's a good thought to end on, Jeffery, because there's a lot of life wisdom right there. And again, very much thank you for sharing your thoughts here, and based on a life journey, that itself is quite a source of wisdom.

Scott Langdon [00:50:10] Thank you for listening to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. Subscribe for free today wherever you listen to your podcasts and hear a new episode every week. You can hear the complete dramatic adaptation of God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin by beginning with episode one of our podcast and listening through its conclusion with Episode 44. You can read the original true story in the book from which this podcast is adapted, God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher, available now at amazon.com, and always at godanautobiography.com. Pick up your own copy today. If you have any questions about this or any other episode, please email us at questions@godanautobiography.com, and experience the world from God's perspective as it was told to a philosopher. This is Scott Langdon. I'll see you next time.