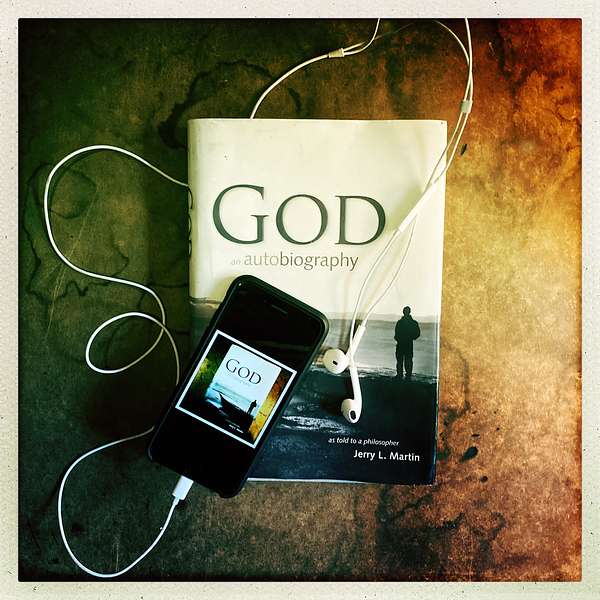

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

160. The Life Wisdom Project | Spiritual Resilience: Navigating Loss and Finding Meaning | Special Guest: Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum

In this profound episode of God: An Autobiography, The Podcast, join host Scott Langdon and join the transformative conversation between Dr. Jerry L. Martin and returning special guest Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum. After hearing from Jonathan about living truthfully, explore this new discussion that unfolds the essence of wisdom- a journey through life that teaches us to discern what truly matters.

Meet Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum, who teaches courses in philosophy, world religions, ethics, and bioethics at Berkeley College in NYC and St John’s University in Queens. He writes and publishes in the philosophy of religion and the philosophy of humor, among other topics.

Jonathan shares a poignant personal story involving loss and a moment of self-discovery during a challenging period. The conversation deepens as they explore the role of prayer and its ability to ground in times of crisis. Jerry emphasizes the importance of quiet reflection, whether through prayer, meditation, or other means, to connect with what holds the most meaning and truth in our lives.

This episode encourages self-love as a foundation for loving others, fostering a love that overflows naturally. Explore the concept of regret and discover the transformative power of embracing the moments of profound connection and fulfillment, even in the face of loss and adversity.

The conversation touches on the profound meaning of religious life, not just in fixing external problems but in providing an internal anchor that sharpens and strengthens individuals.

Tune in to this soul-stirring episode, dive into the realms of philosophy, spirituality, and the human experience, and share your thoughts with us!

Relevant Episodes:

- [Dramatic Adaptation] I Ask God Hard Questions About Ego And Suffering

- [Life Wisdom Project] The Encounter With Novelty And Living Truthfully

Other Series:

- Life Wisdom Project- How to live a wiser, happier, and more meaningful life with special guests.

- From God To Jerry To You- Calling for the attention of spiritual seekers everywhere, featuring breakthroughs, pathways, and illuminations.

- Two Philosophers Wrestle With God- Sit in on a dialogue between philosophers about God and the questions we all have.

- What's On Our Mind- Connect the dots with Jerry and Scott over the most recent series of episodes.

- What's On Your Mind- What are readers and listeners saying? What is God saying?

Resources:

- READ: "The Soul is at One with God"

- THE LIFE WISDOM PROJECT PLAYLIST

Hashtags: #lifewisdomproject #godanautobiography #experiencegod

Share your story or experience with Go

Share Your Story | Site | Facebook | Instagram | Twitter | YouTube

Scott Langdon [00:00:17] This is God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. A dramatic adaptation and continuing discussion of the book God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin. He was a lifelong agnostic, but one day he had an occasion to pray. To his vast surprise, God answered- in words. Being a philosopher, he had a lot of questions, and God had a lot to tell him. Episode 160.

Scott Langdon [00:01:07] Hello and welcome to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. I'm your host, Scott Langdon, and this week on the podcast, we bring you a very special discussion between Jerry and his dear friend Jonathan Weidenbaum. If Jonathan's name sounds familiar to you, it might be because he was Jerry's guest for episode 107, our third in the Life Wisdom Project series right at the very end of 2022, just over a year ago. He returns today to discuss his thoughts on episode 13 of our podcast: I Ask God Hard Questions About Ego and Suffering. After a very difficult and trying year Jonathan's perspectives have been challenged and stretched as he has had some questions about suffering of his own. Here's Jerry to introduce Jonathan a little more deeply. I hope you enjoy the episode.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:02:00] Jonathan Weidenbaum is a professor of philosophy and religion at two New York colleges. He is an intense thinker and a probing teacher. When he has time, he travels to Asia, visits religious and other cultural sites. Having a good eye for what is striking and significant, he brings back photographs that are often exhibited. Unlike thinkers who wrap themselves in abstractions, Jonathan puts ideas to the test of life. And in his written work, acknowledges those tragic dimensions from which less courageous thinkers avert their eyes. He has recently faced tragedy in his own life, the kind of tragedy that threatens to render life absurd. How to deal with suffering and how to learn what suffering can teach us are at the heart of this episode.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:03:27] Well, Jonathan, I'm so pleased to have you as a –.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:03:32] Thank you.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:03:33] My co-discussant on this Life Wisdom episode- episode thirteen. And the episode begins with my feeling flattered by the responsiveness. A very eminent intellectual, a name you would recognize, but I'm not publicizing and worrying about ego. And then I end in the hospital with Nurse Ratched and a medical assistant who's violent almost, so crude.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:04:04] I laughed at that.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:04:07] Prompted by reflections on suffering.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:04:09] Right, right, right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:04:11] So and then we go from one to the other by a circuitous route. But I was wondering, Jonathan, were there things in terms of life lessons - you know, how to live - were there implications here that surprised you or even shocked you? Or did it mainly seem to kind of cohere, to be confirmatory of your own instincts?

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:04:36] I wouldn't say shock. I would definitely say this chapter was full of real wisdom. Three really substantial nuggets of wisdom.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:04:49] Okay.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:04:50] The first, of course, you just got into yourself. You know, you just presented the distinction between self appreciation and ego. And that sort of – and I'm reminded, I remember the last time we had this discussion and I brought up Ralph Waldo Emerson, that wonderful you know, and one finds this theme in him as well. I mean, he decries – he's against that sense of mean egotism that we all have at times, but at the same time, that robust self-expression, self-appreciation, that's joyous and robust and that taps into something larger, and that's healthy. I mean, you could see it would be such an impact on Nietzsche as well who really appreciated Emerson. So that distinction is very powerful and I really appreciate that. That's a real nugget of wisdom. That way of putting it is something I'm very thankful for- thankful to listen to here.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:05:56] Well, here, God expresses it as the joy of being yourself.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:05:59] Yes, of course. Yes.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:06:00] Kind of feel the fullness of your own being. It's bound to you.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:06:06] Right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:06:07] So, that's that sense.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:06:09] Right. That robust self-affirmation itself is beautiful. It's just the separateness of being an ego and the defensiveness that goes along with it and all the sort of calculative machinations of being an ego. That's where the problem lies. And that rich distinction is extremely important because too many folks conflate the two. You know, that's a problem.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:06:33] Yeah. There's a legitimate sense of ego, and then there's an illegitimate sense which is described here as being self-lustful.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:06:40] Yes. Yes. Right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:06:42] Or later, second order attachment to ego.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:06:46] Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:06:46] Where- I'm number one; I'm the most recognized; I'm almost liked; I'm the most beautiful; the smartest, whatever becomes the preoccupation. And that's where you go wrong.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:07:01] Yeah, that was a really, really – I carried a lot from that. And also the rest of it, the second – for me, it's the second one that really hit home. And again, I wouldn't say shock, but I would say it happily reinforced some of the I think the best wisdom, let's say, of my own religious tradition. I mean, I, myself I am not practicing Jewish person, but –

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:07:26] And, Jonathan–

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:07:28] Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:07:28] What are you calling the second one?

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:07:30] The theme of not so much – don't aim at a union with Me, says God, don't aim to become one with Me in some sort of easy mysticism sense, but rather align yourself with Me, be a partner with Me, you know, form a harmony with Me. That was a very, very, very powerful set of teachings. And I really, really appreciate that. You know, and I'm sure you've heard a lot of people of Jewish extraction talk about things like tikkun olam to repair the cosmos. And now don't get me wrong, with Hasidism and other movements within Judaism, Judaism definitely has its forms of ecstasy. It has its ideas of mystical union as well, but they're not as emphasized as this idea of being a co-creator with God, merging your purpose with God. You know, doing a – carrying out the mitzvot, the good deeds, and trying to correct the world, so to speak, as a way of aligning oneself with God's plan. And that to me is very, very powerful. You know, it's in a way, it is a kind of union, but it's a union of purpose, not union of being, you know, not a loss of the self into the one, let's say, you know, again, not that that's absent.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:08:40] Right. Right.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:08:41] But it's just sort of – it is not as emphasized. And I really appreciate that teaching, that's a powerful one. And I really mean it, I mean, this chapter was full of real – and of course, the third one, the third one is suffering as –

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:08:58] Well, let's pause on the second one for one moment.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:08:59] Sure.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:09:00] Your Jewish background –

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:09:02] Yes.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:09:04] I'm told here – this seems to me a very Jewish thought, Old Testament though at least.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:09:11] Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:09:15] You don't need purification, transformation, it is obedience. Obedience.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:09:17] Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:09:18] Often say of Jews– what does it say in the Old Testament? Do and remember, I think are the two.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:09:24] Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:09:24] Do as I say and remember.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:09:26] Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:09:26] Here, obedience is at the fullest transformation. And that's a lot of what people say well, you try it, you start following the commandments, eventually it'll make sense to you.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:09:42] Like any major world religion, Judaism has different chapters and it's been moments of its development.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:09:48] Yes, of course.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:09:48] And certainly one finds – I hear something of the Hebrew prophetic tradition here that would be so important for Christianity and Islam as well, to align your will, to walk humbly with your God and to carry out the commandments of God and to carry out a special destiny that God has for the prophet, but also post-biblical Judaism as well in its mystical traditions and its moral teachings and its philosophical developments. This idea of being a co-creator with the divine and, you know, carrying out acts of good deeds in the cosmos as a way of correcting the fundamental sort of rifts that are in the – that are even within God's own being. Unifying- even God requiring a kind of unification through human fidelity and in good deeds. So –.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:10:37] Yes.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:10:38] So, it rang very pleasantly to my Jewish ears, this teaching. And I recognize some of the roots of these, you know, some of the similar teachings in the heritage I came from. But then of course the third one that's suffering and pain are – I mean, this is – what is suffering? Suffering is the condition of what makes life serious. Right?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:11:00] Yes.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:11:00] Does not allow us to lead lives that are frivolous, and it sort of rescues us from that, and sort of, forces us to kind of, you know, to take things seriously. And that's a powerful teaching as well. Maybe a little easy to forget when you are suffering, but nonetheless. I have a feeling I know why, Jerry, that you've enlisted me for this chapter.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:11:28] Yes.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:11:28] You know, you've known me for some years now.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:11:31] Yes.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:11:31] You know, you've known me through a happy moment when I met someone wonderful and got married.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:11:38] Yes.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:11:38] A year ago, she went to heaven, of course, and making me a widower. By the way, just under a month ago, I lost my mother, so.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:11:48] Oh, yes?

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:11:49] It's been a year of loss. And, you know, she was ailing. She was not – it was not a shock. It was a surprise how quick it was, but, you know, she was not in the best of health and she already had the beginnings of dementia for a few years. It was like there was a sense in which we were losing her a little bit. She had the integrity of her personality, of course.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:12:12] Okay.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:12:13] Her memories were going, and so, you know, it was not a – it was still, of course, a sad thing, you know, to lose one's parent and making me an adult orphan, I guess, I mean orphan is the term used for a kid, but you know what I mean. It's now that I – now that both of my parents have moved on –

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:12:33] Did that have an implication for you? I know in my parents last year – my mother was a very difficult person in my life.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:12:42] Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:12:42] And I suffer from that childhood thing, devoted to me but didn't quite know how to do it well.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:12:49] Right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:12:49] And yet I always tried to be a good son. And each time we would visit, she had years of poor health at the end, and they were in California, before leaving and returning each time I would think, "Is there anything I've left unsaid?" That if she were to pass away tomorrow, which could happen, that I would regret.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:13:13] Mm.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:13:14] And I don't – I mean those are difficult reflections often of is there something I would now do differently if I had it all to do over? Because that's part of what you learn, right? That's part of what you learn through –

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:13:29] Jerry, November 16, 2022, it was my wife's birthday.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:13:36] Yes.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:13:36] And, you know, I had a night class. And I was on the way home on the train and I was like, you know, I'm just going to buy this can of beer, sit on the train with this can of beer. And I'm not going to worry about getting flowers and chocolates tonight, you know. Tomorrow, I'll tell Kasia tomorrow that we’ll celebrate.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:14:01] Oh, gosh, Jonathan.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:14:02] So, I get home and, you know, we had a little tiny little argument, it wasn't you know, she's not a petty person at all. You know, it's not like she was angry, I didn't – but just like, you know, she wanted to celebrate a little bit that night. I said, I was like- no. And so we had a little argument, you know, words came from me that should have – maybe more harsh than it should have been. Of course, she has incredible patience, so it didn't bother her too much. She knew I loved her, but still, and then, you know, it blew over quickly. And then, of course, she was not around for her next birthday, you know. And so, it weighs on my heart.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:14:51] Yes.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:14:53] Now, I will regret that forever, you know. I will regret it forever. It's just that little bit of moment of selfishness on my part, that little argument, that little moment of heat that really came from me to her, now it's, it will I mean – it's if I could, every inch of my being wants to rewind that clock and would have gotten a whole bouquet of roses and and celebrated with her that night because you know, as you know, it was only a month and a half after that that she had died. And it was only the end of that month we discovered she was sick, and then it was the sort of the end of December when she had passed away, so –

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:15:39] Wow, very fast, very fast.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:15:40] Yeah. Oh, it was like lightning.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:15:41] Incredible.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:15:41] Like lightning. Clearly it was growing inside of her before we knew, you know, but in any sense, the words of God to you are – it's not a shock of being God that this was real, real wisdom here. You know, talk about taking life seriously.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:15:59] Yes, yes.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:16:01] Taking each moment, making sure – It sound like a cliche until you're in it, then you recognize how true. It's almost like when you're a kid and you fall in love for the first time and then you realize every sappy love song. Now you know what they really mean, you know, for the first time. So the idea of hugging your loved ones and not wasting any time, my God, was that driven home to me and continues to be so.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:16:26] You know, Jonathan, your regret is in a way –.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:16:29] Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:16:29] You're a current version of a bouquet of flowers. You know? I mean, that's part of the role of regret, you might say. And in whatever way, she can now be aware of that, who knows, those things are hard to understand, but she would appreciate that, right?

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:16:46] Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:16:47] She would appreciate that, and would be, you might say, better than a bouquet of flowers. Right?

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:16:52] That's right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:16:53] Because this is one way that you experience and express your love for her.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:17:02] Right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:17:03] Right? This is your love for her.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:17:05] Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:17:05] Being fully embodied in that regret.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:17:08] That's really the truth. That's the truth. You know, so no matter where she is and, you know, I don't know if you know this, a few months ago in October, I went to Poland to put flowers on her, the place where she's interred- her ashes are in the cemetery of the town she grew up in.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:17:29] I see. I didn't know that.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:17:31] Oh, that's right. Yeah. Yeah. And I put some flowers also on her little brother's grave. When Kasia was younger, she lost her younger brother, and so, you know, I originally had volunteered to bring Kasia's ashes to that cemetery, but then the mother pleaded me to give them the ashes so they can go a little bit earlier but doesn't – so the point is that the ashes were there, they were interred. I went to visit, you know, and these are, moments like these are, whether she can see them or not, and I hope she can – I don't know what to think about what happens after we pass on, of course – but certainly life takes on more directness, pregnant with more meaning and the importance of each moment, you know, made even more important against the backdrop of this loss. And it is certainly the case that this chapter definitely rang home some of those facts, you know.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:18:33] Yeah, yeah. I would think for people in general going through whatever suffering it is, as there are so many different kinds of suffering. There can be being fired from a job, maybe expelled from school, there can be doing things that taint your own character in a kind of indelible way, it seems.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:19:18] Right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:19:18] And there's just physical pain that can happen in so many different ways. But I think the take away is you can't stop all of that- is to try to learn from it what you can learn.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:19:34] Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:19:34] Think that this isn't meaningless. And everything you describe, Jonathan, in a way, this is a lot of the meaning of life that you're expressing here that came through in this whole thing of first meeting her.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:19:48] Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:19:49] Connecting, falling in love, and moving on to build a life together, which is then, you know, I use the word tragically here, which I don't use for normal suffering.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:19:57] Right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:19:57] But where it interrupts the drama of your life, the story of your life, and of course, story of her life in the shocking way that cuts to – it's why people start deciding life is absurd and meaningless, but in fact, this is where a lot of the meaning is found.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:20:18] That is another strong insight. One silver lining against this very dark cloud is that nihilism makes even less sense to me now.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:20:29] Is that right?

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:20:30] Yeah, it makes less sense because if nihilism is the idea that there's no inherent meaning to things, this tells me just how thick, full of meaning life really is. Even if, by the way, even if one is hesitant to accept overarching metaphysical meanings.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:20:50] Right.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:20:51] Theistic belief, wheels of birth and death, karma, what have you, still in these moments you know in the knowledge that you have to – don't postpone seeing old friends, you know, don't postpone hugging the people that you love and what have you, you know, the fleetingness of life. And that's kind of what God teaches you in this chapter as well. God says suffering, you know, among other things, it's sort of the suffering you had when you had that heart attack that you would be in the hospital with Nurse Ratched's sister, you know, the teaching being, of course, that it's to remind you, it focuses you on your mortality.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:21:35] Yes.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:21:36] And you would express then your love for Abigail and that love, of course, also gets channeled to God. So, certainly being aware of one's own mortality, you know, is itself a powerful, powerful form of meaning.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:21:53] Yes. Hard for people when they're– Abigail and I were talking about in some context today, I guess how getting older has affected us.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:22:02] Right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:22:02] Becomes, you start thinking about your mortality in concrete years. Will I ever buy another car, for example? I don't much like the one I have, but will it ever make sense? And how when you're young, the future just seems indefinitely open. You know you're not going to live forever. You know, it is an abstract proposition. But –

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:22:27] It's more concrete –

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:22:31] It feels like that. It feels as if it's going to be completely open ended and go on forever. And I'm contemptuous. I was waiting, waiting, waiting in a doctor's office.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:22:41] Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:22:41] Just to an absurd amount of time- a whole people group of people were waiting- a whole room full in the waiting room and speaking to the nurse, I said, "Why does –?" And this doctor does this all the time. He schedules people- more people than he can meet. And she said, "Well, they think these old people don't have anything to do." And of course, for me it's exactly the opposite. Anything I'm going to do I've got to do today or tomorrow at the latest. But anyway, time is a precious thing and it's actually precious at every age. And part of my sense – this goes to whether she can understand, you know, knows your regret and the love that that regret embodies and expresses – my own sense is every moment of time is you might say in the ledger of reality. It's happened. It's there, it's in the records, it's in the books. And that is not erased. Nobody goes back and erases.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:23:41] Right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:23:41] And that would include wrong things you did. They kind of are there in the book of events. And so I have some very real kind of full bodied realism about those things. The good things people did, the good things one caveman did to another, a kindness- that's in the books. You know, that's a fact. It's a kind of, you might say, a moral fact about a certain point in time. And those facts are not erased anymore than Caesar crossing the Rubicon is erased.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:24:10] I suppose the most you can do is recalibrate the meanings of the past.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:24:14] Yes.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:24:15] And erase the facts of the past. Right?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:24:18] Yes. Is it difficult, here you've been through what seems to me just an unbelievable suffering. I just don't well know how to process it because it's not quite like any other suffering that I've encountered. It's so dramatic, so rapid, so soon on a new love and a new marriage.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:25:01] Yeah. Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:25:03] Is it hard to go from that back to that first insight in this episode- appreciating the joy of being oneself?

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:25:12] That's a great question. On the one hand, it makes you appreciate the value of your everyday life more. Or I think- that I wake up still breathing.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:25:22] Yes.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:25:23] You know. Because you realize that that doesn't – you're not guaranteed that. Also, being an educator like you, you know, you were an educator for a long time, I'm an educator now for a good number of years myself. I've had students over the years that lost their children, you know.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:25:41] Wow. Yeah, yeah.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:25:41] You know, I mean, what do you say to something like that? I'm the son of a – my late father was a Brooklyn homicide detective. This is a man who was a cop who investigated murders in the worst areas of the city during the seventies and eighties, during the worst moment of the city's history. And he would tell the stories when family was around. And, you know, then you realize, look, I also have students in my class that come from parts of the world that knew, that know conflict. We see it jumping out at us from the news, but people who really come from it. So, certainly it humbles you a little bit that when you go through something that, you know, you're part of the brother and sisterhood of humanity that when we all go – and a lot of us do – go through these things. Others- you realize others have been through it, it kind of solidifies your sense of belonging to, I don't know, to the species, I guess. Because we all lived through these things, and again, I guess that goes back to the taking life seriously part. You know, and I'm thankful also for the doctors and the nurses, even though in the end they could not stave off what happened. They tried. They tried, and I'll never forget the way, you know, we were in the ICU ward, and I wrote up a whole piece about this, by the way.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:27:12] Really?

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:27:13] Yeah. Because it's – I'm someone who's been teaching bioethics for a long time. Then all of a sudden, I find myself in the middle of a dilemma myself. Kasia's parents were persuaded to not have the machine shut off, but the palliative care were pressuring me to shut off the machine. And so I was caught in- I, of course, it laid on my shoulders legally. So palliative care met with me personally a number of times. So, but, you know, it's interesting. So, to tie this back to what I was talking about in terms of increased empathy toward others, you know, for a long time I've been teaching, you know, these scenarios, in the history of bioethics, like they're abstract thought-experiments and they're fun to talk about, but there's always a little bit of a distance from it. But when you're in the midst of it, tugged on by different forces and it's on your back and it has to do with the person you love who's on their deathbed, you know, all of a sudden, you empathize in a different kind of way because now you're experiencing it firsthand. So that's yet yet one more example of how when you go through this it kind of – how should I put this? – it sort of reinforces the respect. The nurses and the doctors on the ICU ward, they see this every day, Jerry.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:28:42] Yes, I know.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:28:43] They maintain their composure and they maintain their professionalism. And, the doctor who had to tell me on Christmas Day that Kasia was on her deathbed, versus the ones that helped me argue with some of the family/friends that wanted the machines to remain on, and they were skeptical about medicine, and sort of the real intent of the – Anyway, the point is, you know, I mean, look, my job, I get in front of a roomful of young people or people of all ages depends on the day and time of the class and I articulate ideas that I'm passionate about. But, you know, it really is a true calling for people in this medical profession who have to deal with people at truly their most fragile moments, you know, at their most vulnerable. And what that's like to do that on a daily basis. I mean, you know, and watch people as they die and watch their family around them and, you know, anxious family wanting answers and yet they go through it on a daily basis, you know. So it increased, it really increased my respect for people in the medical establishment, and what they go through. Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:30:00] Abigail and I sometimes say the great thing about being a teacher is that your mistakes don't die.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:30:06] Right. Right. That's – yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:30:07] I mean, you blunder this way or that way –.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:30:10] Right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:30:11] And nobody's going to die. You may do them harm that you did not intend.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:30:15] Yes.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:30:15] Or just an unfairness in, say, giving the wrong grade or something.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:30:19] That's right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:30:20] Reading carelessly. One of the challenges, I think, of the medical profession, I've known people, friends who are social workers dealing with difficult populations, and they have the same challenge, which is to maintain one's compassion.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:30:38] Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:30:38] While at the same sense, kind of protecting yourself.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:30:43] That's right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:30:43] Every time you have a patient, every time a doctor loses a patient, they can't just go into conniption fits or to deep despair or something, they have to handle it with some degree of distance.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:30:54] Sure. That's right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:30:55] And there's always that danger of the medical professional becoming, well, like Nurse Ratched, you know, just kind of robotic or –.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:31:06] Callous.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:31:06] "Let's wrap this up." You know, that kind of crudeness.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:31:11] Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:31:12] And I've been impressed by their ability to balance that in my own care in many cases, though, not in this particular case that I talk about.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:31:23] You know, on top of just the trying to gain the skill of grace under fire but also simply, it goes back to the idea that you learn what matters. You really learn what matters in times like these.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:31:43] Yes.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:31:44] There's a sense in which I'm walking out of this situation a different person. I mean, it's not a surprise to say that, of course, you lose a spouse, you know, and now I lost a parent. Of course, we go through life and we go through things like this. You don't leave the experience the same person you were when you first went through it. But, you know, if it doesn't crush you, if it doesn't shatter you, it sort of hones that sense of purpose that you have as a human being.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:32:12] One definition I've seen of wisdom, which we often get through just living life, is learning what things are important.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:32:20] Yes.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:32:21] And I remember talking to one guy who is very successful in his business and doing this, that and the other thing. It was hard for him to learn the distinction, he put it, between what's urgent and what's important, because you can spend your whole life chasing after the daily urgencies, you know.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:32:39] Right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:32:40] The impingements. And you need to pause and wait, what's important? And about some of that advice I was given, you know, start every day with prayer. And of course, prayer is powerful for me. Prayer, meditation, just some quiet time. And then to not follow orders, but get in that sort of harmonious relationship, and for people who – for me, God is very realistic and full bodied and meaningful, but for many people it's not, especially in our era.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:33:09] Right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:33:09] We're 21st century people, after all. And it's an era where we are not very superstitious, let's say, and we don't personalize everything. And so I think- if you don't pray, even if you don't meditate, try to get in harmony with whatever seems most meaningful to you. Because, life – things aren't all equally meaningful. So, try to discern, and the quiet time seems necessary to this. It can be a walk in the woods, but quiet time. Try to discern what's most meaningful and in that sense, most true about reality- or the most important true aspect of reality. Connect with what's most meaningful.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:34:02] You know, it's funny. Walking to my place of work in midtown Manhattan there are always these Orthodox Jews standing out front of the Chabad center. Chabad is as you know the largest Hasidic-sect of Judaism. You know, if they think you're Jewish, they ask you, "Hey, did you put on your tefillin today?" The fact is, of course, we know they're called tefillin, and usually I just kind of rush past them or I'm busy, you know, and I've got to go to work. I got to make sure I'm able to get these papers done in the morning or get my courses prepared. Which I could do at any speed. It doesn't matter. You know, I just kind of brushed past them. I'm always too busy. I can't be bothered. So, a few days into Kasia's sickness when we learned that it was a cancer that was already metastasized, once again that morning, I'm heading to the office and I kind of pass by them and I'm busy, I'm busy. And all of a sudden two blocks passed, I said, "You know what? Wait a minute. Wait a minute. I feel I need to do this," and I turned around and I ran back. I'll never forget the man standing in front of the building. This Orthodox Jewish man seeing me running back, you know, and just smile from ear to ear. You know, and I came to him, I put on the tefillin and I prayed inside. He brought me inside to pick up the Torah. You know, I'm a Levite, so I did my reading from the Torah, what have you. Okay. In the end, Kasia passed, but I think the true miracle here is the way it grounds me with a sense of purpose and meaning. And it certainly did. It just felt really, really right. Just like now with all these horrific things going on halfway around the world.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:35:55] Yes.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:35:55] You know, you see all the intense pressures you feel you feel like if you're Jewish and I'm sure if you're Muslim as well, you feel like you're on the world under the world's eye when these heat up, and then you feel prejudice, a little bit, aimed at you in some context, in some ways. It just – I I can't fully explain why, but to further your anchoring in your whatever religious tradition you come from, it just feels right. It just works somehow. It unifies you in a way that nothing else does. Or certain things do actually, when you go through pain, it sort of helps to bring an integrity over you that you didn't have before. But in any case, I mean, that's a relation- that's how I found praying works in this context.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:36:55] I always feel – different from – some people take great offense if someone says, "I'm praying for you," or something. I always think- great! I can use all the help I can get. And I have a friend who is a conservative Catholic, you know, strong, strong Catholic who over lunch one day just kind of probed me, why wasn't I a believer and why didn't I have this, that and the other thing? And were there particular objections? And she had suggestions, I could read such and such. She knew- she could refer me to Father So-and-so, who was a great intellectual, and he could surely explain everything in a way that I would get it. Well, some people would take offense at that. I thought, "Here's a woman who cares about me." So, that was my reaction.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:37:47] I feel similarly. When Kasia was very ill then after she passed and then after a little less than a year later, my mother passed, one of my colleagues, wonderful Catholic woman, told me that she goes to church, she lights the candles for Kasha, for me, for my mother. And, I mean, I just – I welcome it, it just feels great. It feels great that people are devoting what's most – they're aiming their heart towards you, and look, every bit helps. It helps somehow. It just does.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:38:22] And one of the things that struck me was your response made that guy's year.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:38:28] Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:38:28] You know, he's out doing this thankless task all the time.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:38:31] Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:38:31] And everybody rushing by somewhat irritated- at least impatient.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:38:37] That's right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:38:38] You didn't invite this. Anyway, but, you did! You responded and you got out of it your version of what they were offering. Right? It was a deeply meaningful experience for you.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:38:54] It most certainly was. Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:38:57] Yeah.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:38:57] Yeah. I think that is one profound meaning of the religious life. I live- I lead a secular life, but I understand. And I understand the meaning of a religious life in some sense and in what it brings us. Even if in the end, 20 or 21 years ago my father passed, and then my wife passes, and you pray, and it doesn't seem to sometimes fix the world outside of you, but it fixes you in a sense. It straightens – it makes, it sharpens you in such a way and brings an integrity to you in a way that you can then help to change things, at the very least it seems to do that.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:39:44] Yeah. And one of the messages here in this episode was you need to love yourself.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:39:53] Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:39:53] Ideally, the way God loves you, which is without reservation. And that has nothing to do with thinking you're perfect or anything like that. It means that for the act of love, your imperfections are simply irrelevant.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:40:08] Right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:40:09] They're irrelevant, and one reason for loving yourself as God loves you is that then that opens you to loving other people.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:40:22] Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:40:22] You're kind of filled with love, and maybe – there are probably many things that can help a person achieve that. Again, I always speak in God-language, but there are probably many ways of taking meaning into your life. Meaning in concert with other people, with friends, and can be in religious contexts. It can be in some other context, literary or artistic or musical or whatever. Scholars do it together in a scholarly mode, but take that, and then you can respond because your own, in a way – with adequate self-love, your own love is kind of somewhat taken care of. You're not walking around with total depletion all the time, a kind of neediness demanding that every person do something to make you feel better.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:41:14] Right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:41:15] You know, but you instead can give them love, appreciation, support, help.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:41:22] Right. A love that overflows. Flows.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:41:25] Yes.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:41:26] Flows out of you naturally, rather than trying to grab on to someone you need, you know, different. I like that. That's real wisdom.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:41:35] Well, thank you, Jonathan. It's a pleasure always to talk with you.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum [00:41:39] Thank you.

Scott Langdon [00:41:52] Thank you for listening to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. Subscribe for free today wherever you listen to your podcasts and hear a new episode every week. You can hear the complete dramatic adaptation of God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin by beginning with episode one of our podcast and listening through its conclusion with Episode 44. You can read the original true story in the book from which this podcast is adapted, God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher, available now at amazon.com, and always at godanautobiography.com. Pick up your own copy today. If you have any questions about this or any other episode, please email us at questions@godanautobiography.com, and experience the world from God's perspective as it was told to a philosopher. This is Scott Langdon. I'll see you next time.