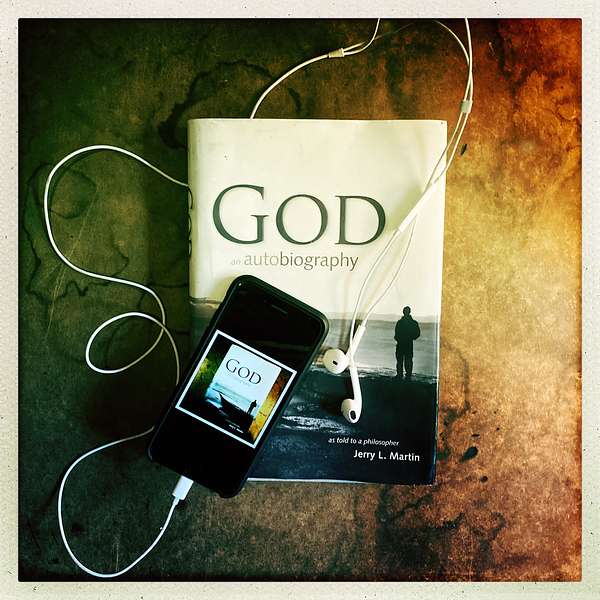

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

165. The Life Wisdom Project | Exploring Spirituality: Meditation to Quantum Science | Special Guest: Judy Dornstreich

Join us in welcoming Judy Dornstreich back to The Life Wisdom Project. Judy, whose journey has taken her dancing around the Caribbean, joins Jerry for a profound discussion on a different kind of dance - that between the conscious mind and the universe's divine pulse. Drawing from transformative experiences and wisdom gained from spiritual teachers, Judy imparts insights that resonate deeply.

In this episode of The Life Wisdom Project, Jerry and Judy delve into a conversation about episode 14: "Exploring the History of Humanity's Relationship with the Divine."

Judy shares captivating stories from her time living in New Guinea, embodying the spirit of a true seeker. Together, they peel back the layers of everyday awareness, exploring the intricate relationship between consciousness and awareness. Their discussion traverses the realms of science, free will, and the supernatural, advocating for a more expansive and open-minded scientific inquiry.

Though rooted in her Jewish upbringing in South Philadelphia, Judy's explorations have transcended geographical and spiritual boundaries. She has sought wisdom from diverse traditions and spiritual mentors, including luminaries like Swami Chinmayananda, a renowned teacher of Vedanta. Today, Judy continues to share her story and insights, fostering conversations on spiritual living that draw from multiple traditions and her rich life experiences.

Relevant Episodes:

- [Dramatic Adaptation] I Learn the History of God's Relationship with Humans

- [Life Wisdom Project] Spiritual Balance and Oneness

Other Series:

- Life Wisdom Project- How to live a wiser, happier, and more meaningful life with special guests.

- From God To Jerry To You- A series calling for the attention of spiritual seekers everywhere, featuring breakthroughs, pathways, and illuminations.

- Two Philosophers Wrestle With God- Sit in on a dialogue between philosophers about God and the questions we all have.

- What's On Our Mind- Connect the dots with Jerry and Scott over the most recent series of episodes.

- What's On Your Mind- What are readers and listeners saying? What is God saying?

Resources:

- READ: The Great Apes Are Wonderful Creatures . . . So Close But Yet So Far.

- THE LIFE WISDOM PROJECT PLAYLIST

Hashtags: #lifewisdomproject #godanautobiography #experiencegod

Share your story or experienc

Share Your Story | Site | Facebook | Instagram | Twitter | YouTube

This is God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. A dramatic adaptation and continuing discussion of the book God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L . This is God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. A dramatic adaptation and continuing discussion of the book God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin. He was a lifelong agnostic, but one day he had an occasion to pray. To his vast surprise, God answered- in words. Being a philosopher, he had a lot of questions, and God had a lot to tell him. Episode 165. And hello, my friends, to all of you. Welcome to God: An Au tobiography, The Podcast. I'm Scott Langdon and today we are thrilled to bring you our 14th edition of The Life Wisdom Project with Jerry's very special guest, Judy. Judy was with us for episode 129 of our podcast: Spiritual Balance and Oneness, and she returns today to discuss episode 14: I Learn the History of God's Relationship to Humans. It's in this episode that God asks Jerry to dig deeper and look not just at science but at the history of science. If you remember Judy from our earlier episode, then you already know why we needed to have her back for this wonderfully thought-provoking discussion. I hope you enjoy the episode.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin:We're talking about episode 14, and it begins with a statement from the great physicist Schrodinger that the eternal world and consciousness are one and the same thing, inspired by quantum mechanics. And yet I'm told, no, that's not the right way to go. But what is the right way to go? Well, it doesn't sound all that different. Let me quote that, as God speaking, "I am the point of interaction between human beings and the world. I am the medium through which human beings and the world." And I say, " is mind the medium?" "Yes," so in addition to, I think the picture, there are human minds, there is the world, they're both real, but there's also divine mind, divine mentality, let's call it, present in both us and things. That's all over the place. So that seems more like a nuance of difference. And I know you've studied these things. I mean, one reason I thought of you is obviously you've studied, unlike most of us, you've studied with a real guru. Right? One of the masters, and who was that?

Judy Dornstreich:Well, I had several, because there are steps, but the main guide, the Satguru. There's things called upagurus, which means step by step in the steps, the upaguru, but then the Satguru is the one that hits you in the head and you go yeah, I get it. And that was Swami Chinmayananda, and actually it's interesting because when I first read that I thought you know this word consciousness I don't like so much, but what if he used Chinmayananda's word awareness?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin:Oh, okay, yes, awareness.

Judy Dornstreich:I like, because that sometimes it's simpler. It's simpler and we'll step to the year, the later years, when I finally said to him so I know the, as the Bible says, God says I am that, I am that, the thing that I am. I know I am this, I know that I am that I am. Why aren't I enlightened? Right, and he looks at me. He said you're still in your intellect. Be that.

Judy Dornstreich:Be that awareness. You're still like your awareness is received on the screen of your intellect, but that's still an external thing to awareness itself.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin:Yeah.

Judy Dornstreich:If you be that awareness, that's different, that and its timeless. It's just awareness.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin:Just is.

Judy Dornstreich:It just isness; exactly. And that isness, that aware being is throughout everything. All and everything, as Gurdjieff would say, is you know, boils down to that awareness. I mean, that's what I got. So then I fetched a plane to my, to Dayananda, who was Chinnayana, chief disciple, and came to this country and was teaching as well, and I actually had an ashram here and I said to him, so I can be that quick, and then I said, what do I do?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin:And that's why people meditate and so forth.

Judy Dornstreich:Well, that's the practice. You do it and I have a really good girlfriend who I think you may know her name is Abigail and when I first was discussing this kind of stuff with her I said I'm the worst meditator in the world and she said she's the worst meditator in the world.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin:She meditates and she says she thinks about something.

Judy Dornstreich:The thing is that there's always this dissatisfaction that you can't hold it longer and have the door, the great you know stuff happening to prove that you've done it right. And I've kind of given up on that. If I could just be awake and aware and be that, sometimes in light, I mean. I think the practice then becomes see if, when you walk out the door and touch the mezuzah, if you're Jewish which I've stopped doing, but that was what's also called a stop in Guruji Fouk Stop and just be, be that, and then you're going to be lost in the body, the intellect, the heart, whatever's going on in the equipment which I find is a really good term, the equipment, meaning your heart, mind and body.

Judy Dornstreich:That's the stuff the being aware, being is embodied in, so to speak, and it demands all your attention and meditation is pull your attention back from that and get to be familiar at least with the silent being aware source inside. And you know, I mean maybe a baby in the belly is already doing that, but boy, do we forget. I mean, here's an image I have of my first baby looking at a window and going ooh. I mean, it's so entrancing when you are born into this world. He's in an infancy and he's like ooh, and you get lost in it. Or until somebody says wake up.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin:Yeah, one notices with very small children. I've been a parent. I mean, I am a parent, but I've been a parent of small children and the way they take in experience up to about the age of two or so is just whoa. You know, they're mesmerized everything that comes along aot's It's t's all amazing. Except they don't have the concept of amazing because they don't know what's not amazing. But they just take in everything in that whole direct way. And I guess for me the life of prayer is something like that, but of course it's not quite silent. There is silent prayer and you have to have what I find I have to have an extremely quiet mentality. So it's a lot like the meditative mentality.

Judy Dornstreich:And that's what the rituals.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin:Just distracted and pushed from left to right and everything. I can't pray. Well, I have to just get a direct connection and then see what I receive, without trying to twist it or manage it or whatever to receive what I receive.

Judy Dornstreich:Yeah, yeah, and the prayer-- formal prayers are actually just a step in the quieting down, because you need a transference. For some people, I'm just remembering an experience that had that was really great, music..

Dr. Jerry L. Martin:Yes.

Judy Dornstreich:It's something that can grab your attention, not only attention of the mind, because after all I mean the complexities, but music is something that will do it for me also, the just paying total attention and good music will engage your intellect. Because I mean that guy who wrote that music is really doing something with this form, like really good artwork is a different form, and then with music it also hits the heart. It does something. Not just playful music will make the heart laugh, but that Bernstein music also. It's like whoo, I can really feel that. And then there's the body which responds to it. So one time I was dancing to some music in a group of people, sort of a meditative type of people, and I got totally at one with the music.

Judy Dornstreich:In the dancing and I wasn't even aware of who I was with or what. I was just one with the music and dancing. And then I hear somebody say that's our Judy. And I went ugh, a nd I thought yeah, this is where meditation takes you.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin:Yeah, yeah, and there are in the experience, without the official act of meditation. There are experiences that are meditative in character and I'm often given in God: An Autobiography, on musical analogies. I'm not, I like music, but I'm very unskilled at music. Singing. I love to play the piano, except I'm still just practicing. I never develop any facility at it, but so I'm very distant from thinking of life in terms of music. But I'm constantly in prayer, given the musical analogies and music you describe it so well, Judy that one immerses oneself. I mean, you're talking about being it, being that's what the music you really become the music, that's what you're describing. And so we're embodied, and I don't put that aside the way some traditions do. We're embodied, our bodies become part of that. that whole of us, which is mind, soul, heart, body, you know, all of us becomes that music. And that may happen for some people in religious ceremonies, I don't know, maybe they're mainly preparatory.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin:--tw-t --tw-skew-x: 0; --tw-skew-y: 0; --tw-scale-x: --tw-scale-y: 1; --tw-pan-x: ; --tw-pan-y: ; --tw-pinch-zoom: ; --tw-scroll-snap-strictness: proximity; --tw-ordinal: ; --tw-slashed-zero: ; --tw-numeric-figure: ; --tw-numeric-spacing: ; --tw-numeric-fraction: ; --tw-ring-inset: ; --tw-ring-offset-width: 0px; --tw-ring-offset-color: #fff; --tw-ring-color: rgba(59,130,246,. 5); --tw-ring-offset-shadow: 0 0 #0000; --tw-ring-shadow: 0 0 #0000; --tw-shadow: 0 0 #0000; --tw-shadow-colored: 0 0 #0000; --tw-blur: ; --tw-brightness: ; --tw-contrast: ; --tw-grayscale: ; --tw-hue-rotate: ; --tw-invert: ; --tw-saturate: ; --tw-sepia: ; --tw-drop-shadow: ; --tw-backdrop-blur: ; --tw-backdrop-brightness: ; --tw-backdrop-contrast: ; --tw-backdrop-grayscale: ; --tw-backdrop-hue-rotate: ; --tw-backdrop-invert: ; --tw-backdrop-opacity: ; --tw-backdrop-saturate: ; --tw-backdrop-sepia: ;">Judy Sort of in trying to put a dervish you know, yeah, or those kinds of yeah, those kinds of practices, the rolling dervishes.

Judy Dornstreich:There's another thing that really happens, and I don't think my poor children they had the opportunity to learn to do this or to get to do this or be this with, but they resented having to help on the farm. But I will tell you, Mark, as well as me, I can tell you that there are times when you are doing something farming and or gardening, I mean, let's say, gardening even is better because it doesn't seem as vast as farming. You know although, let me tell you, driving a zero turn mower can't get any better than that but you're out there breathing big yogic practice, breathing air, fresh air, because you're living on a farm and you're not in the middle of the Lower East Side and you're breathing clean, fresh air, and you're out in maybe, the sun and a little bit of breeze. So, physically, you're out in the sun breathing fresh air.

Judy Dornstreich:You have to focus your mind. You Say you're weeding, you have to, there's a purpose to free the basil plant from things that are going to take its nutrition away. So you have a purpose and your hands are in the dirt and you're feeling what you're doing and you're paying total attention and you're at one with the activity and then all of a sudden you go. Ah, I am completely awake, paying attention, being here now, as the wise man wrote a book about that. Be here now and gardening, dancing is one way, and woo gardening and farming, yes indeed.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin:You know, I've seen you describe in an email or something that you're joy. I don't know if it comes in the spring and the ground is kind of muddy and the earthworms come out and you're sinking your fingers into the new, the soil that's coming about through this great process. It's quite extraordinary and you are one with that process.

Judy Dornstreich:Yes, you're part. I mean you, the earthworms, the, you know, oh, we need a drizzle now. Oh, we've got to-- Whatever, you're part of the whole thing. And you know, when you talk about the teachers, the gurus, I had a teaching from a friend of mine when I was in college, a sophomore in college, and you have to take political science or some other thing like that to fill the requirements. This is at Penn. And I have a friend, very tall, one of the only African Americans who was at Penn at that time, because this is, I mean, this is like 1961 that we're talking about, and we're walking down college walk and he's a political science major and I had to take political science and I am growling and quenching. This is so boring, how can you stand it? And from his great height, he looks down at me and he says, get into it. And the thing was, I was resisting it because it was boring, and so I did, and what do you think I got in the class?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin:Yeah.

Judy Dornstreich:You know, and it was a real lesson to me about getting into it. T hat's what he said.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin:And that moves my thinking to another part of the episode. Toward the end, toward the very end, I'm told this is about my interaction with God. Because I'm always asking questions and God seems to kind of object to this and I said, oh, am I not supposed to think about these things? Well, He says don't stop thinking, but think in a different way. Don't work so hard to figure everything out. And then He says two more things that obviously kind of supply the reason for this d"on't try to figure everything out. When you try to figure everything out, you try to make it rational. And when you try to make it rational, that means you try to fit it to your preexisting categories and what they're trying to be is open to something new and different. And I think of you in another connection here, Judy, which is encountering another culture, and you and your husband, anthropologist in Borneo or someplace

Judy Dornstreich:Papua New Guinea.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin:Okay, New Guinea.

Judy Dornstreich:In the Stone Age.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin:With a Stone Age culture.

Judy Dornstreich:Yes.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin:And so you can't go in and say, oh, I'm going to as, oh, the typical say, the merchant coming through would do, parse it in terms of some preexisting quote rational framework, you're going to have to get there and listen, right?

Judy Dornstreich:Yes, and learn what their rational framework is and how it melds together not with yours but with the other aspects of their framework. They have a whole life and one of the things that was remarkable and you think about the kinds of things that go into making you a "seeker. I mean, I always was that myself, since a little kid, really looking, sitting on the front stoop with my father. We're looking at the stars. This was in South Jersey when you could see the stars on the front stoop before Cherry Hill was. This is Haddon Township before Cherry Hill was built and the light pollution was ruined, all the stars but or didn't ruin the stars, blocked out the stars. So we're looking at the stars and I'm asking him questions. I'm about 14. And I'm saying so, where does it end? And he says it doesn't end. And I keep pressing him and he says it keeps going.

Judy Dornstreich:No, there is no outside and I could not grasp that with my intellect. I couldn't picture it, I couldn't grasp it and I said okay, and I walked, I sort of slammed the door, going into the house and I remember passing a mirror and thinking briefly, and I had a happy childhood, if I could get on a spaceship and find the answer to this, but never be able to come back, I'd go. I would go because I want to know what this thing is that we're in, and years later I was listening to Swami Satchidananda, who was the first teacher that I had, also excellent and he said I can't remember what he said, but I went, I'm on the spaceship. I'm on the spaceship and I'm going to see where it takes me.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin:I sometimes say that religious or spiritual people, there are two kinds of them, what I call seekers and finders. The person who's rock-ribbed in a tradition is a finder, but in fact the best finders remain seekers and we all know that their own literature testifies to it in any given tradition. And the best seekers are also finding something-- bread crumbs along the way.

Judy Dornstreich:That actually again Gurgif, saying being, i or a teacher because Mark was in the Gurgif work and I went a lot and until life just got too insane on the farm and I had a fourth kid and I said I can't do this, I can't do any more meetings. But in the Gurgif work it says stay on the seeking side.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin:Yeah, yeah.

Judy Dornstreich:Yeah, because otherwise, once you find, okay, you're filling in all the crossword puzzle pieces, you think you got them all but no, zoom, zoom, something else is going to happen. That zoom, such a thing, then, is a Zoom. We wouldn't have even conceived of it then, as I mean, might have conceived of it, but being a reality, that you and I are talking in this kind of way, and you know, I really wouldn't mind zooming with some creatures on another planet, oh, please could we just have a conversation. So I'll Zoom, you know, Zoom me and I, because some other creatures-- I mean there has gotta be, but we don't know yet.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin:Yeah, yeah.

Judy Dornstreich:Some day we'll find, oh man. I'd love that.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin:Well, there's always new stuff. However great our religion or our philosophy or our worldview may be, there's always more. There's more. One of my teachers I often quote, Philip Wheelwright, a wonderful human being and wonderful teacher, used to object to people who say nothing" but he was what I call a humanist with a high ceiling. Because we don't know what is up there, so never say nothing but, because you don't know that. Always say, and he would capitalize it- "there's something more and be looking for something more and different. And, going back to encountering the Stone Age people, one of the things you had to do, I sometimes talk about conceptual empathy, which is getting yourself not only to know how it feels to be this other person in a situation, but how it is

Dr. Jerry L. Martin:How do they make sense of their world, their culture, the various things that happen to them as they go along in life? And because it's a culture that survived, at whatever level it survived and is functional, functioning in some way, and they understand something.

Judy Dornstreich:And it was very hard to find uncontacted people, people who weren't already changed. I was sent actually by my buddy an article about New Guinea and some upheaval in Port Moresby yesterday and he sent back a thing I said, "they sure don't look the same."

Judy Dornstreich:I mean they're all wearing Western garb. But of course they were really curious. But they were curious about everything, about us. I was the first white woman they ever saw and they had once or twice seen a patrol officer. They'd look at my palm and they'd go, oh, pink. We were not interested at that time.

Judy Dornstreich:That was during my period of non-religious. I don't believe in all this that you know, it doesn't make sense to me. It changed eventually but intellectually I sort of rejected the whole Judeo-Christian model which is of big daddy the string puller and it just didn't seem real and I want reality. I've wanted reality since I slammed the door and said I'm going to get on the rocket ship if you offer it to me, but I want to know what really this thing is and if there is a God, I want to know what that is. You know. Anyway, they had--

Judy Dornstreich:We didn't investigate their beliefs in that way at all, except that we were observing every single detail of this people who were still using stone tools and one of the things that was evident and it was probably planted the seed in these. You know, I have a master's degree in counseling psychology and Mark's got a PhD in anthropology and we've become farmers. That's what we wanted to do and the seeds were planted in New Guinea because we observed that one of the things about these people were they were a part of the natural world, of they're a part of their environment and saw themselves as a part of it. There's the pigs, there's the people, there's the plants, there's the sun, da, da, da da, and all of it works together in such a way that everybody survives as best they can. And we didn't ask what do you think?

Judy Dornstreich:We never did ask what do you think happens after a person dies? We didn't ask that because we weren't interested, but and perhaps we would have been able, towards the end of our stay, to understand in their language what they were saying. And we had some interpreters who had married into the group, who had learned Pigeon English 15 years before. So basically, we Pidgin English and then we learned enough, Gaudio Enga, in order to say he didn't really say that. You know, fill it out a little bit to the interpreter, because we know enough.

Judy Dornstreich:And we never asked the question, but we observed that everyone was aware of the interactions of all the different aspects of nature and they were at one with nature. Perhaps, if we asked them, I'm just guessing right now, but perhaps if we said, well, what happens when you die? They would say well, I mean, obviously you're feeding the trees and then these trees feed and maybe, if you get planted over here or over there, you're going to make food for the pigs and then the next generation of people eat the pigs. They very much saw themselves as part of the whole thing.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin:Yes.

Judy Dornstreich:That's beautiful.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin:The other thing I was going to mention is that right at the beginning of the episode I was told to look at science, but well, I looked at the wrong science, somehow although the wrong science that Schrodinger quote at the beginning, identifying world and consciousness, seem not all that different from the divine mentality permeating every day, but okay, these are nuances and probably in both Hindu and Buddhist traditions, and maybe some Western traditions as well, one finds something closer to the version I was given. The divine mentality is providing the links you might say. But the context of that was that I said well, I thought you told me to read about science, and so here I'm reading great physicist about quantum mechanics and his speculations from that in terms of how it fit the Vedanta view of the world. And I am told read the history of science, our current view of things and the history of things that didn't work out like astrology.

Judy Dornstreich:Like astrology. One of the things is that I, about science, is my brother is a big deal scientist guy. One of the things in our discussions which we've had as adults because one of the developments of my intellect and I would highly recommend that people who are listening that have children, young children those kids either sleep in the same room or spend but lots of times together. Because my brother and I were 19 months apart- that's pretty close. We discussed everything as we were growing up, because we slept in the same room and yappity, yappity, yeah. And I still maybe it's less now, but through all my growing up and young years, I would process trying to figure out something as if I were talking to Alan. I was having a conversation because of the backs and forths and one of the things this now big deal scientist has said is science is a methodology.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin:Yes.

Judy Dornstreich:Don't consider oh, everything that science tells you is the final word, because we're going to have more tools for the methodology. But it is a methodology and that's a great value of science. So don't put it down, even though it can't give you all the answers. And that was-- it's helpful.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin:Oh, it's absolutely helpful. I used to see these B pictures. They would run Friday nights, haunted house or something and then they would bring in the local scientist from state university, a professor of science who was filled as, and he would say oh, I'm a scientist, we don't believe in ghosts, and like what you're learning from your brother, he should have said I'm a scientist, let's investigate, let's check it out, let's check it out.

Judy Dornstreich:But when we're saying that matter and energy are part of the same thing, maybe ghosts are some residual energy from that person. I mean, who knows? I'm not saying they are, but let's check it out. And one of the things is oh, I wrote it down because I realized this is-- science is the methodology by which we figure out how God does it.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin:Ok, yes, that's-- say that again. That's a wonderful--

Judy Dornstreich:Science is the methodology by which we are figuring out how God is doing it. Wonderful, wonderful.

Judy Dornstreich:Not only did it in the beginning is doing it right now. I mean, are we, you know, all of the advances that we've got? We're doing it. In some respect there is free will, I believe to a degree. Lot of, I mean, am I gonna raise my hand and lower my hand? Well, it depends. If I have to scratch my head, I'm gonna raise my hand. If there's no reason to raise it, I probably won't. So it's a response to conditions, but sometimes I just might go boom just to say I did that because, you know, I wanted to prove a point. That's also a because, actually, it's a result.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin:You know children do it out of a playfulness. With us, you know we're illustrating a point. But the children do that sort of thing all the time without reasons. You know, just to free play.

Judy Dornstreich:Free play, although even then I can remember being at the kitchen table with my fourth child, Ava. Across from me, she lifts up her spoon and she pretends she's gonna put it in her ear and looks around the table to see if you're laughing and I went, whoa.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin:Oh, that's amazing, because that's-- that is very smart, that reveals multiple levels of intelligence already. What I'm doing, how it looks like what I'm doing, what people think I'm doing, and, moreover, that's kind of funny.

Judy Dornstreich:And I'm gonna see if I'm getting a reaction. I'm looking around, reacting. And now she's got a two year old and I think I'll do that next time I'm with him and see how he reacts. Look, I just learned this from your mother.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin:No, that's wonderful. Yeah, I am always struck that the wrong view, the kind of about science is that it's a set of like doctrines, sort of like a catechism. In fact, someone, a religious man talked about the secular magisterium, you know, with teaching authority of the church. They think they have a right to boss the world around with regard to worldviews and everything.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin:And one of the things I was struck and came into this exchange with God, or at least my background of it, was we only rather recently discovered, supposedly decided, that most of the matter in the world is dark matter. To think that we can't see what no censor would pick up. That is just inferred, because for certain laws to work as they do, there must be more matter, assuming our laws are right, of course, you could go the other way, and maybe uh, oh, this law has got to be revised because it's not working, but then we'd have to throw everything up and easier to postulate dark matter. And then later they decided oh, the same thing is true with energy. Most I don't know if it's most of the energy, but there's all this energy that's also undetectable. But, this is the whole world, the whole universe has many dark matter and energy and it's a recent discovery. We didn't know this, so this is not settled.

Judy Dornstreich:It isn't settled. And it's enough to make me shake my fist at God. Like, come on, I'm wanna get on the rocket ship and get all the answers and you're gonna tell me-- first you're gonna tell me about dark matter, then you're gonna tell me about multiple universes. I can't even deal with this universe, let alone multiple.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin:Multiple universes is very puzzling. It's a postulate, it's an imagined thing that would solve one way of solving certain issues in physics. If you say well, there's more than one universe, and time going backward. If you look at the equations about time, they're actually don't say a before and after. It kind of doesn't matter.

Judy Dornstreich:Oh right. That's another one.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin:Anyway. So you can imagine, but I can't imagine. There are all these movies. You can make a movie about going backward at a time, but you always end up with intolerable paradoxes if you really try to think it through. So anyway, who knows?

Judy Dornstreich:But that was one reason to go to New Guinea. To go to New Guinea for me, because basically I wanted to go on the rocket ship. I wasn't gonna get on a rocket ship, so let me go, so to speak, back in time to before things were this complex and see what's what. And it was-- I didn't get really any answers, except great gratification to have had the privilege of having fun at home- this is a real world experience in what could be considered way back in time.

Judy Dornstreich:(Right, right, it's like time travel.) And belonging there and you know, laughing with people.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin:And it's something we need to do today with each other, because in some way we inhabit different intellectual, spiritual, social worlds and the other always looks so alien to us. Easy to dismiss them or, if they have irritated us, to denounce them or something, but (and it's- getting worse)-- Even if we're gonna disagree with them in the end, the first challenge is make sure you understand them. You have to point of view, a different philosophy, whatever.

Judy Dornstreich:And how they got to the place that they are that's so ridiculous to you,

Dr. Jerry L. Martin:Yeah, what did they draw on that made it make sense to them and maybe if you look at that it might come to make more sense to you. Or you might see oh, they made a mistake, they drew on it in a way that led to a wrong inference. That can happen, (that can, both can happen) but at least now you understand it and in fact you can explain it to people better, because you've paid enough attention to them in a sympathetic, empathic, enough way.

Judy Dornstreich:Ah, that too, and attention, that's one of the things paying attention.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin:Yes, yes.

Judy Dornstreich:Which is like waking up. I mean paying attention. How does-- I've been taking sips of this water, but really I'm more attentive to our conversation, so I haven't tasted the water. I mean the juice, you know.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin:Exactly exactly.

Judy Dornstreich:You know, well, it tastes good.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin:It tastes good. Well, that's a wonderful place to end. We'll end with it tasting good. The conversation itself tastes good to me, Judy. (Absolutely, yes.) And seeing and talking with you is always a great enjoyment.

Scott Langdon:Thank you for listening to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. Subscribe for free today wherever you listen to your podcasts and hear a new episode every week. You can hear the complete, dramatic adaptation of God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin by beginning with episode one of our podcast and listening through its conclusion with episode 44. You can read the original true story in the book from which this podcast is adapted, God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher, available now at amazon. com and always at godanautobiography. com. Pick up your own copy today. If you have any questions about this or any other episode, please email us at questions@godanautobiography. com and experience the world from God's perspective, as it was told to a philosopher. This is Scott Langdon. I'll see you next time.