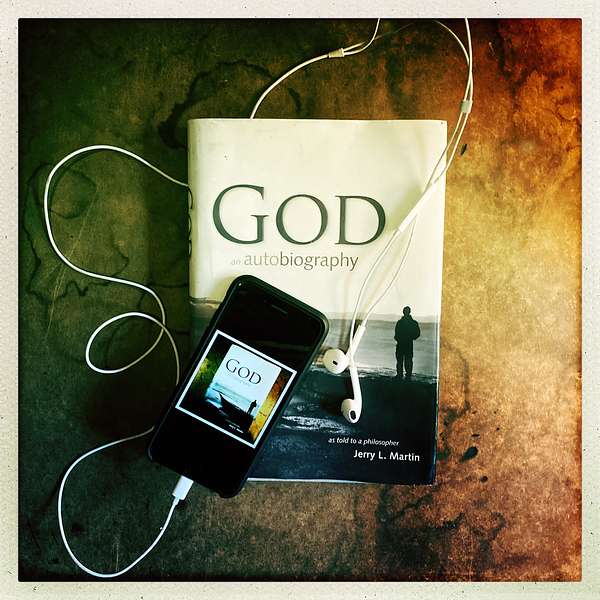

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

172. What's On Our Mind- Divine Presence: Acting, Experience, and Alignment

Join Jerry L. Martin and Scott Langdon for a captivating discussion on spirituality and storytelling. They explore the complexities of human ambition, historical interpretation, and religious narratives, finding rich insights in characters like Lady Macbeth and ancient Greek tragedies. Through engaging dialogues, they illuminate how acting serves as a conduit for understanding the essence of God.

Their exploration extends beyond academia, delving into personal transformation. Scott shares how portraying roles like Lord Aster can reshape an actor's worldview, echoing the transformative power of stories in our lives. From interpreting myth as truth to exploring divine empathy, they uncover profound intersections of acting, storytelling, and spirituality.

Join them in reconsidering the boundaries between fact and myth and embrace diverse perspectives. This episode offers profound reflections on divine collaboration and truth in human experience.

Relevant Episodes:

- [Life Wisdom Project] Insights from Hasidic Tradition and Philosophical Ethics | Special Guest: Dr. Michael Poliakoff

- [What's On Your Mind] God and Daemon | Good and Evil

Other Series:

The podcast began with the Dramatic Adaptation of the book and now has several series:

- Life Wisdom Project: How to live a wiser, happier, and more meaningful life with special guests.

- From God To Jerry To You: Calling for the attention of spiritual seekers everywhere, featuring breakthroughs, pathways, and illuminations.

- Two Philosophers Wrestle With God: Sit in on a dialogue between philosophers about God and the questions we all have.

- What's On Our Mind- Connect the dots with Jerry and Scott over the most recent series of episodes.

- What's On Your Mind: What are readers and listeners saying? What is God saying?

Resources:

- READ: "Evil is a Power of its Own."

- WATCH: Does God Still Speak With Us?

- WHAT'S ON OUR MIND PLAYLIST

Hashtags: #whatsonourmind #godanautobiography #experiencegod

Would you like to be featured on the show or have questions about spirituality or divine communication? Share your story or experience with God! We'd

Share Your Story | Site | Facebook | Instagram | Twitter | YouTube

Scott Langdon 0:17: This is God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. A dramatic adaptation and continuing discussion of the book God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin. He was a lifelong agnostic, but one day he had an occasion to pray. To his vast surprise, God answered- in words. Being a philosopher, he had a lot of questions, and God had a lot to tell him. Episode 172. Welcome to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast.

Scott Langdon 1:13: I'm Scott Langdon and this week, Jerry Martin and I talk about What's On Our Mind. One of the great pleasures for me in working on this podcast is having the opportunity to regularly speak with my spiritual mentor about what it means to live a life with God. This week, Jerry and I talk about truth and factuality, about stories and about how God is always present as a partner and co-creator in the stories of our lives and in the lives of everyone and everything around us. If you'd like to share your story of God, please drop us an email at questions@godandautobiography.com. We always love hearing from you. Thanks for spending this time with us. I hope you enjoy the episode.

Scott Langdon 2:02: Welcome back everybody to another edition of What's On Our Mind. I'm here with Jerry Martin and we are really excited to discuss some things that came to our minds from the last couple of episodes, and specifically our last episode, number 171. What's On Your Mind where we revisited an email from Matt Cardin, a terrific writer of horror fiction and a philosopher at that and, Jerry, when we were talking back and forth via email about what to do for this episode and how it was going to shape out, you brought up this idea of talking about Matt a little bit more and the things that we talked about then and what was on your mind coming up?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 2:41: Yeah, I always go back and reread. I tend to reread the transcripts because I can do that quickly and see what themes have been emerging, what ideas have been brought to our attention, and one was in reading the email from Matt Cardin, who is a writer, prompted some thoughts and we ended up talking about- I brought up Lady Macbeth, for example. This is a fiction character, right? And yet, Lady Macbeth is not someone just invented. Oh, let's invent some imaginary figure like winged horses and this kind of thing. But Lady Macbeth is a vehicle for exploring a certain kind of evil that you might say is at the heart of people, or many people, maybe all people. Tragedy like that, a drama, brings out the characteristics in a kind of pure, dramatic, and extreme form, often. They show the limits, the certain limits of human life, what it is like if you, everyone, has ambition okay, that's fine. But what if you let ambition take over your whole life to the point that you're murdering on behalf of it? That's ambition pressed to the limits and beyond the limits and becomes something other than simple ambition.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 4:16: And we talked also about in the discussion with Michael Poliakoff, the Life Wisdom discussion with Michael Poliakoff, who's a Jewish scholar and also a professor of classics and currently teaching, of course, on antiquities greatest hits, he said. And what are the greatest hits? Well, once again, what do we go to? He's teaching the Oresteia and the tragedies that plumb the depths of human life in exactly this way. And in that play, what he mentioned was even the gods have been unable to stop humans from fighting and feuding with each other. And Athena, the patron goddess of Athens and a symbol for wisdom, throws up her hands. Well, it's just beyond me, she says, and she sets up a court of human beings and tells them you all figure it out. And that's also a kind of Jewish theme that, okay, people have to struggle with this, and Michael Poliakoff saw this as the positive message. Okay, we may squabble and be extremely imperfect, but God, or the gods in the Greek context, have given us the wherewithal to deal with these problems, has given us reason, compassion and, you might say, a whole arsenal, a whole toolkit of ways we can deal even with our own conflict and our own evil. And mediation, arbitration, debate, discussion, help, reaching out, community, solidarity, all of these devices are also available to us. We don't just have to run amok like Lady Macbeth, or these warring city states which made so much of ancient Greek history and brought them down eventually because they just couldn't stop fighting with each other. And so someone else Persians or somebody just came in and took over. I was also, in that What’s On Your Mind, Scott…

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 6:41: You talked about the remarkable production you had seen, I believe in high school. You had all read King Lear and the Royal Shakespeare Company put on a performance in a very unusual way and I thought that was so remarkable. I just hope you'll tell us again and don't spare the details if anything in a fuller version, because I think it was a remarkable thing that for you was remarkable as a kid, remarkable in retrospect to you as an actor. But you have insight into it now. You didn't have then and of course most of us do not have that insight. We've not been actors and it sounded like an impossibility. So if you could just tell us again about that special production of King Lear.

Scott Langdon 7:31: Well, what drew me to storytelling all along, and storytelling in the theater was always big, full productions of things. And a lot of that had to do with movies too, the big movie musicals of the 40s and 50s, you know, Singing in the Rain and all of them. Oliver was a big movie, just grand spectacle. And anything on stage, the more people, the bigger the sets, the better the experience, I thought. Well, in high school we went to see this production of King Lear done by the Royal Shakespeare Company who was on tour and they came to Philadelphia, to the Annenberg Center. This was in the early to mid 80s and in that production there were only six actors. One actor played King Lear the entire time and the other five played, and I think there were two women and three men, three other men and they played the rest of the characters.

Scott Langdon 8:32: It was a bare stage and just a couple of chairs for props to show some location and of course there's the stocks where you know the things happen and that chair was turned around and made into stocks and made into a throne and made into a bed and those kind of things. Just very creative staging, costumes very basic, not even indicative of any kind of period, just sort of clothes you would wear at rehearsal maybe. And looking through the playbill, I could see three older men, gray hair, grayer beards, and one younger man, maybe in his late 20s or 30s, and those were the only men in the cast. And I kept thinking well, this guy's playing King Lear, and this guy's playing Gloucester and all these others, and this guy's playing all these others, where's the other? Who's going to play Edmund if he's playing Edgar? And reading through I realized this one actor was going to play Edmund and Edgar. Now, the problem with that, as we had already known from reading the play in class, is that Edmund and Edgar fight each other in the end in this big duel.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 9:46: How on earth are you going to do that?

Scott Langdon 9:49: Big sword fight. I don't know. You know I'm thinking, that's what I'm thinking, I'm thinking ahead into the last bit of the play. How are they going to do that? But then the lights sort of go down and then they come up and the play starts and I'm already just into it and this new way of seeing theater captivated me, just the simple-ness of it, just what you could do. Just you don't need the flashy costumes, you don't need all of the huge props, and you don't need all the movie magic, just you're just there in the space.

Scott Langdon: 10:17:And it was amazing and when we got to that scene, that one actor played both Edmund and Edgar in this fight and he fought himself, he parried and changed direction and thrusted and went the other way and then stabbed himself and died and then got up and looked over this place where his body was referring to the body. It was amazing and I completely was entranced and it informed, I didn't realize it at the time, but it informed my acting later on because I just realized the story is the important thing and however you can do this different ways. I realized so many things, but one of which was you don't need, you know, 25 people. You can do it with five. How interesting, like maybe you could do it with all women or maybe you could do it with all men.

Scott Langdon 11:14: You know, it just opened up this whole flood of possibilities of how to tell the story and that there were many, many ways to tell a story. And so that affected not only my acting and my creative world but also my religious life, because as a young person there, I was really struggling with what my religious story was trying to say and was telling, and I was trying to figure out what story do I want to tell about my faith, and that it's different from everyone else's, and maybe there are more ways to tell a story of one's faith and relationship with God than the way I'm being told to tell it. It just it started to open up a whole lot of different cans of worms.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 12:01: Yeah, that's funny. I had a similar epiphany, in a totally different context, I think, in 9th grade, doing a book report, kind of a little paper for a class, on the Spanish American War, and I had at hand several histories and they didn't agree about– They stated a different number of people killed in the blowing up of the Maine. The battleship Maine was blown up in Havana Harbor. That US ship provoked the whole war.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 12:37: And I'd always thought, well, history simply happens, right? It simply happens. And here's certainly a factual matter. You'd think somebody would just have reported it at the time and that would go down in all the histories. But oh, there's something going on here. Either some just got it wrong or maybe they're counting in different ways. And once you have that question, then you can notice oh, there are different ways to count things. You know, do you count just the sailors on board? The people on board, or do you count the people in the docks who are hurt? But that the stories we tell are in part stories by us, right, that's one aspect. On the other hand, especially when thinking of a context of history, but in a different way, of religion, it's extremely important to get it right, not just to make up things but to make up something truthful. And anyway, you saw that in the more existential context you face this question and the existential context of religion, a religious belief in practice.

Scott Langdon 14:24: The story of Jesus, for example, is the story that is foundational in the faith I grew up in. I was christened in the Lutheran church. That was the tradition of my mother and her mother, catholic for my grandmother before that, she converted to Lutheranism, but later, when I was 13, we came to a more evangelical tradition in the Church of Christ and in that tradition the way I received the teaching was that factuality was really important, and when you talk about getting it right, hearing those words makes me feel like getting it right means getting all the facts down about why Christianity, specifically, is the one and only true faith.

Scott Langdon: 15:22: So the idea of, well, just saying the words Christian myth would send so many of the folks who went to church with me into an apoplectic fit. You know just those two words together the idea that a myth is a story and that Jesus is not a story. It was real. In other words, this factually happened and all of these things that you can read in the Bible were as factual as well George Washington chopping down the cherry tree. OK, well, wait a minute, right? So what stories are factual? What stories are truthful? Does truth always equal factuality? A lot of those things came into play in the deconstruction of my faith, where now I see the story of Jesus a lot differently. I still think that there was something good about having to dig into that and try to wrestle with what factuality and truth, how they go together and if they are ever apart.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 16:35: Yeah, that's fascinating. It's funny that mythological language, which is used by a lot of people, also I think the way it would disturb the people you're talking about Scott, in the congregation, assumes myth is false, myth is made up. Myth is simply false and a view I was already kind of contradicting about Lady Macbeth, this is not simply false. No, it's true you don't send the police up to the stage to arrest Lady Macbeth, right? I mean, there is a distinction and that distinction is true.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 17:12: But mythic truth is another vehicle of truth that often seems to express in a profound way something that would be hard to express in a purely literal way.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 17:24: And yet, even for myth, if you go back to Garden of Eden which I guess, I know religious people who take that also literally, but most biblical scholars say Lutheran biblical scholars would treat that stage of the scriptures as something like myth and think that the history part starts somewhere a little later. And at the same time, when you're reading something that is fiction or myth or symbolic, I always feel you lose something if you immediately start saying, oh well, this symbolizes this and that symbolizes that, you treat it as pure allegory and nothing means what it means. You know, in the story it all means something else, which is also somewhat in imposition on the part of the person interpreting the story, and there's something vibrant about the particulars that Adam and Eve ran and hid. The particulars of the life of Jesus, I don't know if he struck what was it, an olive tree that was not giving him what he wanted?

Scott Langdon 18:35: Fig tree.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin: Yeah, fig tree not giving him what he wanted. I don't know if that happened or didn't happen, but I wouldn't want to simply allegorize it, and treat it as not really about Jesus striking a fig tree, but is about something else. It may also be about something else, but if you lose the particularity I think this is generally by teaching Homer's Iliad, I'd want to treat it blow by blow, not just, none of this happened, it's an allegory or something like that, it's a myth, it symbolizes… No, you got to stay close to the particulars and I guess you were having some appreciation of that, Scott, in terms of this very literal treatment by this evangelical tradition.

Scott Langdon 19:29: Yes, and one of the results of that experience with King Lear and the Royal Shakespeare Company was, as I mentioned, realizing that stories can be told in different ways and you tell the same story over and over again because there's meaning in telling the story.

Scott Langdon 19:51: So when I think about story and telling stories different ways, I started looking at other religions and the stories that were being told through them and being able to say, and really hinting at that all along and opening up to that all along, but really not until we started working on this project and coming into contact with God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher, your book, which started all of this, for me and for you know, all of us here, was this idea that God was present in all of those stories, all the germs of all those stories. And now here is God wanting to tell God's story and I just thought, okay, there's something to this idea of telling stories that's at the root of why we're here. And it gave me an appreciation for what you were talking about, just the I'm not looking at which one is the right story, which one is the most factual, but the fact that you know, as God says, I didn't say the same thing to everyone. I said distinctly different things, and so each story has its own thing for me to participate in as an audience member and as a you know practicing actor, living those moments.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 21:15: Yeah, yeah. It's a very puzzling thing and of course I was arguing with God a lot of the book God: An Autobiography I'm saying, well, wait, that doesn't make sense. You know, how could you be behind all the religions when they contradict each other? And God said, yeah, of course they contradict each other. I didn't give them all the same version. And then He explains in three points why He didn't.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 21:38: That they weren't all open to the same, they didn't all have capabilities for the same, and also because of their different capabilities, cultural backgrounds and so forth, their affinities, God was able to show different aspects of God's self to them, or be more accurate to say, different aspects came out. Just as when you get to know a person, certain aspects of them come out from interacting with Scott that hadn't come out from interacting with their next door neighbor and they didn't exactly, you know, plan that. It just comes out that oh, there's this other side to them. Maybe the next door neighbor never would have guessed. But comes out and dealing, talking with Scott about something, or engaged in an activity with Scott about something, and so that richness of the divine is one part of the story and another part of the story... I mean, it struck me at first- God has a story? God's supposed to be eternal, unmoving, static, basically. Not moving through time, and there's a perspective from which, as the book unfolds, from which that is true, but in creation and the real world going on, in God's interactions with us, God has a story and the story is a story of dealing with us and God is developing. We are developing, we're helping God do things in the world that need to be done, that aren't just made up tasks like a computer game, that need to be done, and we're God's partners in that, which is a very rich idea.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 23:27: And you have to ask what are all its implications? But back to getting the particulars, the facts. There are actual facts in spite of all this story. But what one has to appreciate is, like the blowing up of the Maine or the life of George Washington or anything, any particular has multiple aspects and its aspects include things aren't just separate under themselves, islands under themselves, things have relationships. Right? You see, the different object has a different color under different lighting, for example. But that's also true of that object that it's going to have those different colors under these different lightings. And at the interpretive level, looking at somebody's life, the life of Jesus or anybody you want to name them, or Macbeth. Why are there many readings of Macbeth, which is studied up to kazoo? Well, it's because it's a very rich text and these are very complex characters, more complex than your first reading reveals, and it's the 45th reading that you see certain aspects that you missed before, and I would think scripture is much like that.

Scott Langdon 24:48: Yeah, yeah, I think it is too. Regarding something like Macbeth or Hamlet or any of these roles that have had thousands of actors play them over the years. Why do we keep needing Hamlet? Why do we need another Hamlet? If we didn't need this, there would be one Hamlet, the first premiere of it, the first run of Hamlet, and then that would be it. Now, sometimes a play deserves that you know one run.

Scott Langdon 25:54: But the great stories and there are, you know, the great stories, like a Hamlet say, have had thousands and thousands of Hamlets being played and all the other characters being played, and the reason that we need to see them is what you just said. On so many different viewings or readings, you get new things, different things, but also for the actor, the actor needs to play these parts we need to see, you know. Well, here's an example of what I mean. This summer I got to play Paul Sheldon in a play called Misery, which is based on the Stephen King novel and the movie Misery with James Caan and Kathy Bates and it was made into a play and in, I think, 2014, Bruce Willis starred on Broadway and Laurie Metcalf and I got to do that this summer at the Forestburgh Playhouse with a really great team and just a super partner play.

Scott Langdon 26:56: I played Paul Sheldon and Annie was great, we had good friendship. We were there for, you know, four weeks total. And then a month and a half later, at the Fulton Theater in Lancaster, PA, Sarah, my wife and I went to see my friend, Lenine, who played Annie in our Misery, played again with my good friend, my wife and my good friend and somebody I've known for years. In between the theater with Jeff Kuhn, he played Paul Sheldon. So now I'm sitting in the audience watching the woman who played Annie be Annie and this other person be Paul Sheldon, who was me.

Scott Langdon 27:37: So this perspective and I loved it. I mean it was a different take and they obviously it was its own thing and I'm like a fly on the wall watching Annie do this thing to Paul Sheldon while I, Paul Sheldon from our production I'm sitting here watching. It was very strange and odd to kind of have that perspective and be aware of it, and one of the things I learned about it and thought about it in terms of God is that God, in enacting all of us, must also be learning and seeing, and from different perspectives. From your perspective, you see me, I don't see me here, but you get to see me from that.

Scott Langdon 28:17: So God is seeing God in all of these manifestations and being able to be aware of that and think of that that way made me closer to God, made me more. It was those kinds of things bring me more in line with God and make God and I feel like we're sharing this creativity stream together and I just don't feel like God is separate from me anymore. I haven't in quite some time now and it's come out through the vehicle of acting and theater and storytelling for me. For others, perhaps it comes out in a different thing that you're doing, but what I'm confident about is that it comes out in the things that we do, because that's where we in the doing of it and that's where God gets God's joy is in the doing, in the world, being the world.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 29:12:Yeah, I think I was told at some point that we're God's eyes and ears. My wife, Abigail, sometimes says God can't mail a letter. You know, God is not a physical agent in the world. The most pious people who believe in the almighty power of God do not ask God to make their coffee. They think, oh, we've got to do that. That's not… God presumably would be able to make coffee, but even that's not quite clear. Can God come down and make coffee the way we do? You know that's kind of strange, though you could do it in a play or a movie, but we are God's eyes and ears and when you emphasize acting, Scott, God's legs and arms and hands and minds also. But you know, God is seeing the world through our eyes.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 30:12: There's a wonderful theologian that I'm writing about in a book I'm writing called Radically Personal, and I often have trouble remembering her name, but it's Linda Zagzebski. It's a slightly unusual name for me to pronounce. Linda Zagzebskii's a Catholic thinker who wrote, gave a series of lectures that were published, omni subjectivity, a new divine attribute, and she's wrestling with the context of Christian theology, God's supposed to know everything, right. Does God know what it's like to stub your toe? To feel the loss of your partner or a child, or the disappointment, the loss of a job? Does God know what those are like? And if you think about it well, to know them isn't to know them from the outside. We can look and say, oh, Jane lost a job, or Jane tripped and hurt her knee, but we don't quite know that in the fullest possible sense of the word know? To know it you've almost got to be Jane. Right? Jane is having the pain, having the experience, and the argument here is just from a tradition that has God as very transcendent and distant normally, that well, no, God has to be able to have Jane's experience as Jane, not as an infinite, all powerful, invulnerable deity, but as a fallible, very vulnerable, perishable human being and what that's like to lose a job, when this is not only your livelihood but your identity. It’s this job. And God has to be able to enter that. So it's a very striking argument, very compelling. She's a terrific philosopher and logician, but there's something to it, and in a different route somewhat, Scott, that you've come into this in part through the acting analogy.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 32:36: Lady Macbeth comes into reality on stage by being enacted, after all. How does music come into reality? Somebody's got to play it. You know, Beethoven could write all the scores in the world and maybe music theorists could read them, could look at them and say, oh, this is wonderful, wonderful. But it actually doesn't come into fulfillment until an orchestra actually plays the piece and then, much like acting, each one is going to be different and it's a different experience and you can go listen to it every year and get something new from it as a musical experience and all of life is sort of like that, that we have these experiences over and over, but they're so rich that they have multiple aspects. And you're right, Scott, according to God: An Autobiography, God is part of it all. We can relate to God, but God is also all present. There's the divine presence infusion in everything, not as something outside coming into Scott or the things around Scott, but, as you might say, that's almost like what they're made of. You know, this is their innermost reality- is the divine substance of them.

Scott Langdon 33:54: The essential nature of us is God, is God's self.

Scott Langdon 34:00: When I think about the idea of the personhood of God, the story of Jesus is that God came to wanting to know what it's like to be a human, to relate to us, God came down into the flesh and became Jesus and experienced the world as a human, and the idea, the story, is that Jesus now knows what it's like to be– God knows what it's like to be human and knows us entirely. And while that I believe is true, I also say Jesus was never married. Jesus never lived to be 55 and feel what it feels like to wake up at 55 and cry, and Jesus never had to have kids and wonder if they're going to get shot at school. So how are you telling me that Jesus knows everything? I don't get that. I didn't reject it entirely, but I just had that bug in my mind. Well, the way I have come to articulate it is through my experience. I heard a wonderful spiritual teacher named Rupert Spira say you are the experience God is having, and when I relate that to my acting, it's very specific to the role I play and the story that's being told. Peter and the Starcatcher we've talked about that before.

Scott Langdon 35:30: It was a play that I just did this late fall into the winter we closed on Christmas Eve at the Delaware Theatre Company in Wilmington, Delaware, and in that show I play Lord Leonard Aster and he has a daughter named Molly Aster, played by another actress, and I actually didn't know this person before, we worked together on this piece and we've become friends and have stayed friends. In the show Molly has to go through some difficult things and Lord Aster has to witness that and allow it to happen and see her make a choice and see it hurt her and know that it's for the best and be there to support her. And nightly, seven times a week, I'm having that experience as Lord Aster in that moment.

Scott Langdon 36:20: It's not my daughter, Scott Langdon's daughter, it is Lord Aster's daughter and Lord Aster is in that moment and his heart is breaking for his daughter. Now that experience is real. That's happening right there in the moment. Right, it's not the kind of reality, it's not Scott Langdon is the reality I wake up into every day and go to sleep into every night. I recognize I'm not Lord Aster, but I'm changed. I start thinking about the world differently because as Lord Aster, I've gone through this experience and so I think about, Scott Langdon starts to think about his own children differently and his relationship, I think about my relationship to my own daughter, I think about my relationship to my son and my relationship to my wife and all of those things because of being Lord Aster, and so I think God is infused in us, so God knows what it's like to stub your toe because you stub your toe.

Scott Langdon 37:20: God knows what it's like for Jerry to stub his toe, because it's not just that He's with us, He is us stubbing our toe, He is Scott stubbing his toe and Jerry stubbing his toe and he's Abigail mailing a letter all at the same time. It's too much to get my mind and heart around, but that's something I know, the way I know I'm talking to you right now.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 37:42: Yes, yes, I understand that, if we can extend it in this direction. I have the experience of having you enact me, and you have the experience of enacting a living character whom you know, and for me it's not such a stretch, I do not think of myself as an actor, although anybody in that role is in a sense delivering something, but I just try to get in the mind, kind of recall, and get in the mind of what happened at the time God told me this and to try to say it about the way I heard it. That's all. But you're playing a living character that you're interacting with as we recorded the episodes of God: An Autobiography. How would you, the way you're thinking about it now, understand your enactment in the podcast in the first 44 episodes of God: An Autobiography, your enactment of Jerry Martin?

Scott Langdon 38:51:That was profoundly interesting. I've never done a role before playing a real person, where the real person I was in contact with and not only in contact with, but we were working on the piece together, and so you were coming to me with how you or were remembering God saying it, as you just mentioned. You're trying to just deliver it the way you remember hearing it, as best you can. Well, that's so fascinating because if going back earlier in this conversation talking about just making things up, that there's a truth, that something means something, the story of whatever it might be we can't just make up a different meaning for it. There's an intention there. Intention is everything. So when I was reading the scripts that we had finally kind of gotten together and said, okay, this is what we are gonna say here. I'm going through the lines of Jerry Martin that I'm going to say and I'm pondering how am I gonna say this in the right way? So you could say something like well, somebody asks you, how are you? And you could say fine, right. So you could say fine. Or you could say fine or fine, right. So all those meanings, and so you work through like which one is the right one and all I can say about it is that that's the work.

Scott Langdon: 40:22: I went through it and I guess you could say I prayed, I thought, God, how is this? And you would give a line as God and my next line I would deliver it in a way, and it didn't feel right. I deliver it in this way and, yeah, I deliver it that way. Yeah, no, that's better. I just, it just felt like the truth.

Scott Langdon 40:48: So, I have taken that to mean and to feel like that's divine intervention, that that was God and I working on this and I wanted to get to the most truthful rendition of what you say. Now, I wasn't there when you said back to God what you said, and even if I were, I'd be doing it with my voice and my inflection, and just as you are doing it with God's voice, with your inflections and so on. But that's how it came to you, which is interesting because God talks about that some. Says of course I'd come to you in your voice. That's how I do, sometimes, you know. But I learned that as I was working through how to say it, that there was a divine nudge to say yes, yes, this, not that.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 41:37: Yes, yes, and before I've read God's lines, I actually prayed in part to get into the mentality of the original conversation. But I also pray, “Lord, speak through me,” and I pray that before I give talks on these topics. And I've had only one occasion where I felt in a vivid sense of that happening, almost as if I'm not talking at all, even though I had a prepared text. So of course it's my words I'd come up with, but someone, the most spiritually attuned member of that particular group I was speaking to, in my own judgment, she said to me after, “You are not speaking about God, you are speaking from God.” And so she picked up on that and that's sort of ideal. I mean, it's kind of.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 42:45: This is part of the theoretical paradox of what we're dealing with, Scott. On the one hand, God is everything and therefore God is everything we do. You know, God was all the wrong versions also, and in a way, there's no reality outside God. What would that be? I mean, in a sense, there is reality outside God and that's part of the puzzlement. There are the moments where, ah, this is the one that's most divinely infused. The others might have been Scott's flailings and Scott's efforts, but finally, oh, it's like you've got a tuning device or something. Ah, now I'm finally in tune, and it's something like that. That's the phenomenology of it. The experience of it is something like, no, I missed something here, missed something here, and ah, this is it. And it feels like you and God are in sync. And that's what I think.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 43:48: In daily life, you know, we have the Life Wisdom series. In daily life, one of the main things to do is to pay attention and try to fit your actions to what feels inside as if you and the divine are in sync. And it's not a methodology, you know, this is not criteria, not a theoretical deduction, but it's much more existential in total. You know, the total Scott, the total Jerry is at this moment, in this context, in sync with the divine, and okay, that's the thing to do. That's the thing to do. And then, in one way, that's how God lives, you know. But those moments, the different traditions have different names for them. The Jews call them, say you're doing a mitzvah, and that's an act that is in alliance, in conformity, in rhythm with, in tune with the divine and I'm told at one point the plural is mitzvot- that mitzvot create the world. So it's those moments that keep reality going or keep it on track, and that's what we're all about. I mean, that's God's story, that's our stories as well.

Scott Langdon 46:11: Thank you for listening to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. Subscribe for free today wherever you listen to your podcasts and hear a new episode every week. You can hear the complete dramatic adaptation of God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin by beginning with episode one of our podcast and listening through its conclusion with Episode 44. You can read the original true story in the book from which this podcast is adapted, God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher, available now at amazon.com, and always at godanautobiography.com. Pick up your own copy today. If you have any questions about this or any other episode, please email us at questions@godanautobiography.com, and experience the world from God's perspective as it was told to a philosopher. This is Scott Langdon. I'll see you next time.