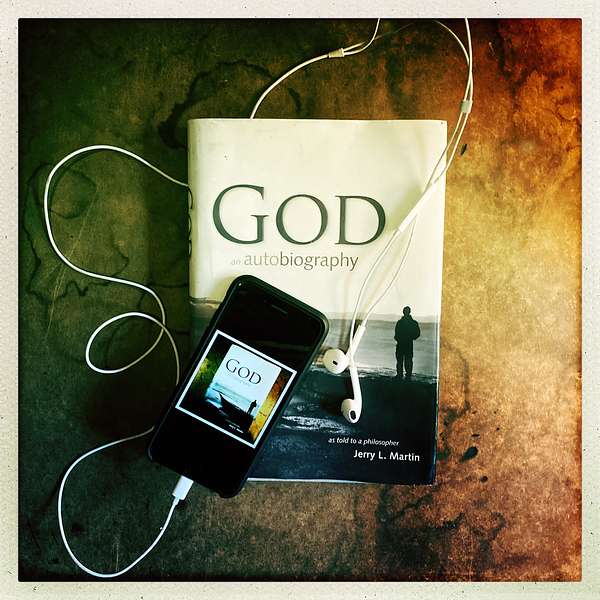

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

177. What's On Our Mind- Beyond Belief: Exploring God and the Human Journey

It's your story. Why not take a moment to travel a scenic and quiet path of spiritual exploration with hosts Jerry L. Martin and Scott Langdon? Join this discussion of divine communication and the transformative power of divine love and reflect on the relationship between faith and identity. Connect with God, share your story, and explore more of God's story with openness and curiosity in a conversation that will inspire your spiritual journey.

Relevant Episodes:

- [What's On Your Mind] Adolescent Journeys: Finding Identity and Faith | The Power of Everyday Faith

- [Life Wisdom Project] Exploring Divine Creation: Beyond Philosophy | Special Guest Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum

- [Special Episode] God Takes Me Back To The Beginning Of Everything

- [From God to Jerry to You] Does God Still Speak to Us?

Other Series:

The podcast began with the Dramatic Adaptation of the book and now has several series:

- Life Wisdom Project: How to live a wiser, happier, and more meaningful life with special guests.

- From God To Jerry To You: Calling for the attention of spiritual seekers everywhere, featuring breakthroughs, pathways, and illuminations.

- Two Philosophers Wrestle With God: Sit in on a dialogue between philosophers about God and the questions we all have.

- What's On Our Mind- Connect the dots with Jerry and Scott over the most recent series of episodes.

- What's On Your Mind: What are readers and listeners saying? What is God saying?

Resources:

- READ: "Do it as an Organic Flow."

- WHAT'S UP WITH GOD VIDEO PLAYLIST

- WHAT'S ON OUR MIND EPISODE PLAYLIST

#whatsonourmind #godanautobiography #experiencegod

Would you like to be featured on the show or have questions about spirituality or divine communication? Share your story or experience with God!

Share Your Story | Site | Facebook | Instagram | Twitter | YouTube

Scott Langdon 00:17: This is God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. A dramatic adaptation and continuing discussion of the book God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin. He was a lifelong agnostic, but one day he had an occasion to pray. To his vast surprise, God answered- in words. Being a philosopher, he had a lot of questions, and God had a lot to tell him.

Scott Langdon 01:00: Episode 177. Welcome to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast, I'm Scott Langdon and this week Jerry Martin and I share what's on our mind. We talk about how it can often be difficult to understand how God could suffer, and what that means regarding our relationship to God and our relationship to one another. If the personal is essentially interpersonal, as God tells Jerry, then God asking Jerry to tell God's story makes all the sense in the world. We relate to each other by telling the stories of our lives to one another. And the personal God who spoke to Jerry and speaks to us all wants to relate to us. If you'd like to share your story of God, please drop us an email at questions@godanautobiography.com. We love hearing from you. I hope you enjoy the episode.

Scott Langdon 02:02: Welcome back everybody to another edition of What's On Our Mind. I'm Scott Langdon. I'm with Jerry Martin here. Jerry, it's great to see you on Zoom here. I love that we can look at each other.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 02:10: Yes, yes. It's a pleasure, Scott, as always. We’'ve gotten back from a trip, Abigail and I, and it was a difficult trip, and then we've had some adventures since then, but it's good to see you and to visit this very interesting recent episodes that are very provocative.

Scott Langdon 02:32: Yes, I thought so too. You know we're looking this week at episodes 173, 174, 175, 176, and this is episode 177. We kind of do these, I like to call them, a unit at a time. You know they start with From God To Jerry To You, and episode 173 in this unit, if you will, Does God Still Speak to Us? And I really liked that talk. The question comes up often with so many people. Is God listening? Does God care? Is God around? Where is God during X, Y or Z? If I cry out to God, is God not only listening, but does He speak to us? One of the things that you suggested in the talk is- God says to you, I'm not a rescue helicopter, I don't come in to just swoop down and do it. I am, however, with you. There's no place that you can go that I'm not there. So there's a comfort in that I found.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 03:42: Oh yeah, that God is ever-present and God is caring. God is actually not just present like an observer, but God is on our side. He's like you know, when you have got a family member in the hospital, may not at that moment even be conscious, but you are present to that person and you are on their side. If there's anything you can do for them, you might say you would, but God, of course, is not in this world in quite the way we are in this world. As Abigail often says, “God can't mail a letter.”

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 04:14: So there are a lot of things, and I was told that, I think about loving, God says, “It's hard on people for Me to love them.” It's like it's overwhelming or something. And then the Old Testament you drop dead if God shows up, you know it's just too much, but I was told in prayer, “Love her; show My love through your love,” and so that's what we're doing with each other, and this is God. Our love is not just a naturalistic response, a kind of elevated sex impulse or something. It actually has a divine component. That's what empowers love, that's what enables us to be loving, and so God is doing that, you might say, right when we love each other. and do each other kindnesses. It doesn't have to be overwhelming love, but you give someone who needs help. The other day, somebody thanked me for just saying a nice word to them, as if, oh God, I needed that. Okay, well, that's letting the divine light show, you might say.

Scott Langdon 05:29: That's interesting that you talk about divine light in that way, because what I was thinking about was a lot of the childhood experiences in my religious upbringing were songs like let your light shine. And I think in most religious traditions there is that kind of admonition to let your light shine, to shine that light. And I often think nowadays, when I reflect on that comment, that God says it's hard for me to love people, hard on them, more like, is what He says, why would that be something? All we want would be love.

Scott Langdon 06:01: Well, sometimes, when I think about this light shining example, I think sometimes you get a light shown on you when you're in the darkness and it's too bright to focus, it's too bright to see anything you know, so it's a little bit at a time. And so it's like the analogy that you ask Him you know, why can't You put everything in my mind? And He said that's not how it works. And you said as a teacher, I understand that you need to give a little bit at a time. So it's a similar thing here. If God were to just be shining all of God's light, it's too much. As a human, we take a little bit at a time and we have to falter. If suffering is the law of growth in the universe, as God says to you, then we have to do the following, we have to be in the darkness a little bit and there comes that bit of plurality or duality, the darkness and the light.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 06:51: Yeah, that's right. Life has that mixture and there are the rough edges, and the rough edges are, in part, learning. That's where you learn and grow and often have insight. The rough edges of life also can be creative. If everything were just placid and orderly and it was like the Buddha's life before he became the Buddha. He was a prince with a wealthy father and they gave him everything. Here are some cushions, here are some beautiful women, here's somebody to play music for you, and you're never out in the weather. You know, somebody carries an umbrella over you and well, that's not quite a life.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 07:39: In the ancient story about Gautama, who became the Buddha, is that one day he travels around and has the person take him outside the palace gates. Traveling around, then he sees people are old and sick and he asks gee, what is this? The person explains people get sick, they get old, they die. There's a funeral going by. They do!? This is news to him and ah, that's how things are. And so then he leaves the palace, goes out into the world and then puzzles and comes to the Enlightenment as a kind of solution to the problem of suffering, and that's almost a natural dynamic of spiritual insight. Something rattles your cage. You're sitting in some placid, complacent, unthinking state and then something makes you think, draws your attention, and then you say what's this? And then, if it's unfortunate, like suffering, what can I do about it? What can be done and what can that person do that will help? And religions offer a variety of—and philosophies—a variety of answers to those kinds of questions.

Scott Langdon 09:01: In episode 174, it was a replay. We were replaying episode 16. God Takes Me Back To The Beginning Of Everything is the title of it, and that's God basically giving you a play-by-play of creation, another sort of vision of what happened, Big Bang, and what that Big Bang was, how, what happened after the Big Bang, that kind of thing and scrambling to bring things into order. It was a fascinating episode to work on, to make, and I felt like I think that was the first time that I really felt this sense of God and I working together on that episode. So it was the first episode when we came back for season two and started doing weekly episodes. Those first 15 episodes, for those of you who might be new to listening to us, the first 15 episodes of this podcast we had done and then dropped them all at once and then it took a little while to kind of figure out how we were going to do it next and we decided a weekly format would be better. So episode 16, 17 and going forward up until now and going forward from now are weekly and we drop them every Thursday, but in that episode episode 16, that we focused on this in this unit…

Scott Langdon 10:25: God talks to you about creation and it really troubles you and it troubled me actually thinking about it and working with it and making the episode that there's so much anthropomorphic language. God is talking about when the Big Bang happens, sort of stretching out His hands and making order out of chaos and maybe feeling like a baby punching out of a womb. He's giving you these examples of how it would be and you're just- God, I have, you've given me this story that just contradicts so much and it just doesn't make any sense. And yet when I was re-listening to it recently, I thought that makes the most sense. God is relating what it was like to sort of birth everything, and we can relate to that because that's what we do. Why not use anthropomorphic language? It seems to make the most sense. Anything that's not anthropomorphic language is us making up concepts and structures. I mean, why not go to the middleman, if you will, and just skip the middleman, I mean, and just go straight to the anthropomorphism.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 11:39: Well, that's right. There's a kind of almost a mythology of intellectuals that these abstractions are more reliable. But the abstractions are just in the air, you might say, things we pull out of some smart brain, you might say. Whereas, much as we were talking about that in Anne Lamott's advice in Bird by Bird, when you have an experience you want to write about, like you've traveled somewhere and here are your impressions of Rome or Shanghai or whatever, you want to write it down just then, fresh, and she says use the words that come to you, because that is the language that the experience actually had for you. You know that expresses the experience, as you felt it.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 12:34: And there was a theologian I read, and I think I quote him in God: An Autobiography, where I'm worried about this anthropomorphism. And then I happened to read this guy, a Dutch theologian, who's saying the experience of the people of Israel with God was such that only the most extraordinary literalism was adequate to the case. The only way to express this was as an encounter with a God who's a person. And of course that's my experience too. It's not the only side of God, that is said. Every time God tells me He's a person, He always adds, and much more than a person. But that doesn't negate or supersede God as a person. And so here He's telling His experience, which He explicates because I think, well, experience, that's a very anthropomorphic term. You know, we have sensory apparatus and so forth. Well, what it's like to be God, that's what He means by experience. There is something that's what it's like to be God. If you are God, there's something that's what it's like to be God. And okay, that's what the experience is.

Scott Langdon 13:48: Yeah, I love when He says to you that's what experience refers to. What it's like to be God is My experience, and so I want to share that with you. And how does God share that with you? By sharing God's story. He says here's My story.

Scott Langdon 14:06: So when we think about how we are made in the image of God, if you wanted to take that as a starting point, then we could say, if someone wanted to ask me what's it like to be Scott Langdon, I would tell you my story and I would say here's what it's like. I would be giving you my experience so far. If I asked you what's it like to be Jerry? You know. But more specifically, what if I were to say what's it like to be over 70? I don't know what that's like you do, and so you could give me that experience by way of telling me your story, because I can't have your experience.

Scott Langdon 15:36: If we are in communication with God and God is saying here's what My story is, I would imagine God would want to know what our story is and you've said that a few times, you know.

Scott Langdon 15:35: God has said, I want to know what's going on with you. And so when we talk to God about I'm having this experience, in one way God already knows, because God is us and God is having our experience and yet the ability to turn around, if you will, and say to God here's my experience, here's my suffering. Do You even exist? Do You talk anymore? You used to talk, You don't anymore. Do You hear me? All of these things. In a sense, I'm saying to God here's what it's like to be Scott.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 16:16: Yeah, and one of the things I always think about prayer and I say this on various occasions, let God know how it is with you, and so it's perfectly fine to be angry at God, to be disappointed at God, to be outraged, you know, why isn't God helping you more? And that's what that earlier episode, one of those recent ones, Is God Listening, I guess was the episode, where one can feel very frustrated. I prayed for my grandmother.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 16:50: But she died anyway. Yeah. So, was God paying any attention? No, but that's where not a rescue helicopter comes in. No, God was right there with my grandmother and God was suffering also. We just this last Friday, lost a good friend and we were visiting his wife left behind yesterday and Abigail is saying the Kaddish, a Jewish prayer that you say for people who've passed away, typically for seven days, and what's the essence of the prayer?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 17:32: It's consoling God for the loss of this good person, of this person God cared about, and so it's entirely… It doesn't express anger, it's out of that deep sense that's in that tradition and of course in many traditions, of God caring about us. And so when this bad thing happens, and of course I'm told over and over, God suffers. God suffers. And you'd think God's so sublime, how can God suffer?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 18:03: Well, God does suffer and it's because of that kind of personal aspect that God goes through you might say mourning. He goes through, oh my gosh, losing so-and-so and regretting whatever suffering was part of that process for that person. And God is suffering doubly because God also experiences everything the dying person experiences, you know, that's how God experiences things in many ways. It’s because of what we're experiencing and God's participation in us or God's identity with us. And so it's not just that God is observing suffering and maybe caring from a distance, writing condolence notes or something, but no, God is right there in this dying man on Friday night and suffering what he is suffering and with the widow suffering what she is now suffering.

Scott Langdon 19:13: When we came to episode 175, I was really excited about that one. That was a Life Wisdom Project, and we had Jonathan Weidenbaum back and Jonathan and you talked about episode 16, kind of broke that down. And looking for what we would talk about today in this episode, I went back and I was looking at the transcript from what the two of you talked about in episode 175. And there was a part that popped out to me that I'd like to talk with you about right now.

Scott Langdon 19:46: At about the 10:51 mark of the episode, if you're looking for timing there on the transcripts, if you're listening and want to get to it right away, Jonathan Weidenbaum talks, Jonathan says, God says, and he quotes you or quotes the book, “Before creation, I am pure spirit sufficient unto myself, I felt I was lacking something grounding, facticity, the blunt materiality, the hard edge to push oneself against the resistance and friction that physical objects have.” And he goes on. He says, Jonathan says, “And you know I was thinking about quotes to talk about. And well, that's one of the quotes, but yet I want to invoke a quote that I find meaningful by way of contrast to this, a contrast in which I hold this quote favorable.” And then he goes and he's talking about the Upanishads. “I hold this quote favorably because in one of the Upanishads, it's understood, in a kind of Advaita Vedanta kind of perspective, which sees this world of plurality as really ultimately Maya, that everything is nothing but Brahman in different forms, the ultimate, expansive, Satyananda bliss, consciousness, awareness.”

Scott Langdon 21:00: And Jonathan goes on. He says, “there's a quote: all fear comes from the other or anxiety comes from the other. That is, if you're caught up in the illusion of plurality and duality, then there's something outside of you that opposes you, whereas if you realize that your true nature is one with the absolute, then duality and plurality are nothing but and you'll see that they're illusions and you're able to shove off the anxiety and fear.” So, what Jonathan, I think, is pointing to is a notion that and I tend to find this in my exploration of that kind of teaching which is, if we can just get back to the oneness and kind of live there in this sort of perfectionism, nirvana place, but that's not the point of being in the world. Being in the world, is this friction that God felt God needed something to push the hard edge against, as we talked about before.

Scott Langdon 21:01: When I think about this, I don't see it, as now Jonathan goes on and says that it seems as if God is telling you something different, or maybe the opposite of this, or pushes back against this, saying if God or Himself wants an outside, an other, without which real relationship is not possible, without which we cannot exert our energies, as with God, so with us." And so what I find interesting about this is I think God is pushing back to say, in part, it's a place of perspective. When you get your identity attached to who you think you are. This human, Scott Langdon, right.

Scott Langdon 22:46: If you ultimately that's it, then you think I was born on February 4th, 1969, and I die whenever I die, and that's it, and in a sense that's true. In another sense that's happening at the same time, when I realized that the essential nature of me is God, then it's just a place of perspective. Then I can see that everything, I can see a thing that's temporary. I can see that everything is temporary, and that goes to God telling you, the difference between us and animals is the idea that we and human beings were the first creatures to have this second order reflection, that we're able to know that we're depressed, we're able to know that we're happy, we're able to know that there's something more than us, and so I find that place of perspective interesting, and not necessarily the goal of being, but rather a place of understanding perspective.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 23:43: Yeah, I think that's a good point, Scott.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 23:47: I thought one key to the ways of thinking about it. You know, God: An Autobiography, God is constantly completely ridicules, you might say, rejects the idea of the world as illusory. So, the fact that God is everything, which of course is in God: An Autobiography, is something I'm told, told repeatedly, that doesn't mean plurality is illusory, it's not that God's being everything trumps the plurality.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 24:22: To be real, God had to come into a world and to be a person, God needed other persons and then you get the otherness that the Upanishads seem to be worrying about, whoa. Then there's another person, and not just me. You know, if I'm Brahman or something, it sounds like it's all just me. But no, here's another person. And there are Indian stories that caution against this. You think some story. I can't tell it very well, don't remember details, but an elephant, raging elephant, is headed for this guy and he's a devout Hindu and he says not to worry. Not to worry, it's just Brahman. He's just Brahman. Well, whoa, he's flattened. So the world is quite real. And I'm told at one point if it's illusory, it's a barrage you can drink water from and that's the reality. And, as you're emphasizing quite rightly, Scott, God values that, the kind of quote from the Upanishads that emphasize fear. When the Upanishads somehow thought of the other, they think of that as a source of fear. It's also a potential object of love, of beauty, of partnership. So this is kind of a little bit of a paranoid escape from the world. Oh, the world can turn against you. Well, it certainly can.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 25:55: And I think, again, your point is right, Scott, about perspective, that I'm told against attachment, but detachment, which is very much emphasized in Upanishad-type traditions, that I'm told attachment is wrong. Does it mean I'm wrong to be attached to Abigail or, just to know, just to my favorite book or, you know, favorite chair? No, no, that's fine. God says it's the second-order attachment where I think, oh, I can't live without this chair, I can't live without this first-edition Dickens or something. I can't, well, and I may have to live without Abigail, God forbid, but we're both mortal and so one of us, unless we go down on a plane together, which is our ideal scenario, is one of us will pre-decease and the other will be abandoned at that point. Okay, those things happen.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 26:55: But otherness is not itself a negative trait, and I think that's a crucial point to hold on to. And identity is not itself a saving trait. You know, in terms of my molecular and chemical structure, I'm identical with more or less everything. So what? That's not a saving trait. So I think the key comes back to that sense of perspective.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 27:22: Okay, the things you care about are right to care about and they're particulars in the world and they're not in the ordinary sense identical with you. But they're also divine, including the horrible people. Saddam Hussein had divinity in him too. He rather spoiled the living out version of that, but as many of us do, as we all do to some extent. But the identity and difference both need to be there. That's part of the paradox, and God is always saying I am both same and other than the world, and therefore same and other than each of us, and in a way God endorses Atman is Brahman, which you might translate into more Western language.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 28:19: Your soul has an essential affinity with the divine nature. You know, they're not alien. You can conceptualize it different ways. It's an inner divine spark, you know, or something like that, if you want. There are different ways to say that, but it's why you, in the end, get what you want. You know, when I challenged Neale Donald Walsch's claims that you always get what you want, well, and I thought well, you don't get what you want. You know, and I think, many examples of not getting what I wanted people I know who fervently wanted something and didn't get it. That's not what their soul wanted. It's God's answer, because the soul is in sync with the divine or is identical with the divine.

Scott Langdon 29: 29: Thank you for listening to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. Subscribe for free today wherever you listen to your podcasts and hear a new episode every week. You can hear the complete dramatic adaptation of God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin by beginning with episode one of our podcast and listening through its conclusion with Episode 44. You can read the original true story in the book from which this podcast is adapted, God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher, available now at amazon.com, and always at godanautobiography.com. Pick up your own copy today. If you have any questions about this or any other episode, please email us at questions@godanautobiography.com, and experience the world from God's perspective as it was told to a philosopher. This is Scott Langdon. I'll see you next time.