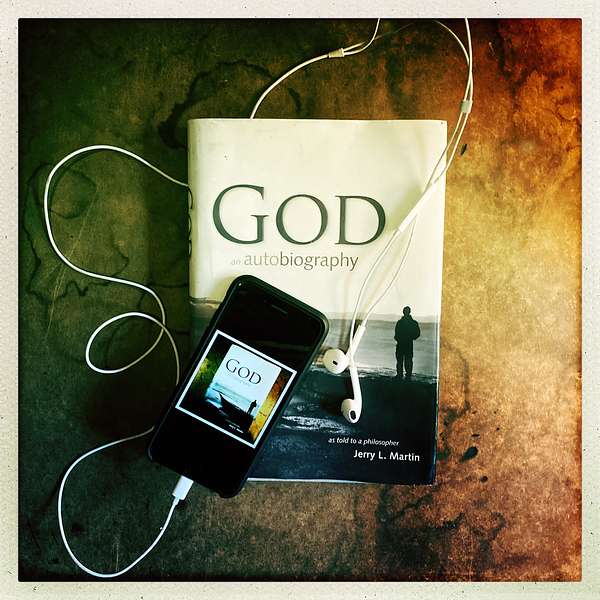

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

131. What's On Our Mind- Trusting God Across Traditions

Scott and Jerry discuss the most recent series threaded with themes of God and religious truth. The conversation goes into Scott and Jerry's religious upbringing and uncovers the limitations and many aspects of truth. Discernment is an essential aspect of one's spiritual journey.

What truths speak to you?

The Life Wisdom Project, with special guest Judy Dornstreich, explores spiritual openness and harmony. What's On Your Mind shares the stories of people interacting with God and each other through godanautobiography.com.

LISTEN TO RELEVANT EPISODES- [Dramatic Adaptation] I Ask What God Is Like [The Life Wisdom Project] Spiritual Balance And Oneness | Special Guest: Judy Dornstreich [What's On Your Mind] Sharing Spiritual Stories And Inner Transformation

-Share your story or experience with God-

God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher, is written by Dr. Jerry L. Martin, an agnostic philosopher who heard the voice of God and recorded their conversations.

The podcast began with the Dramatic Adaptation of the book and now has several series:

- Life Wisdom Project-How to live a wiser, happier, and more meaningful life with special guests.

- From God To Jerry To You- a brand-new series calling for the attention of spiritual seekers everywhere, featuring breakthroughs, pathways, and illuminations.

- Two Philosophers Wrestle With God- sit in on a dialogue between philosophers about God and the questions we all have.

- What's On Our Mind- Connect the dots with Jerry and Scott over the most recent series episodes.

- What's On Your Mind- What are readers and listeners saying? What is God saying?

READ- Too Interesting

WATCH- The Theology Without Walls Mission | Is God Trying to Get Your Attention?

#whatsonourmind #godanautobiography, #experiencegod

Share Your Story | Site | Facebook | Instagram | Twitter | YouTube

Scott Langdon [00:00:17] This is God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. A dramatic adaptation and continuing discussion of the book God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin. He was a lifelong agnostic, but one day he had an occasion to pray. To his vast surprise, God answered- in words. Being a philosopher, he had a lot of questions, and God had a lot to tell him. Episode 131.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:01:13] I like the book, I don't like Sartre, but I like the title Surfing with Sartre. And the point of the book is well expressed in the surfing term. I don't think it would have that much to do with Sartre, thankfully, but, you know, what is freedom? And freedom isn't just soaring in empty space. You know, frictionless space. It's more like surfing where there are circumstances and you're riding with the waves and some of them are kind of hard. And you ride with those two. You say, "Whoa, there's a big one coming." And if you're a good surfer, you know how to handle that. And of course, it's you. You achieve your goals within the surfing when things work out well, and of course, God is providing the surf, a lot of the surf. And then also helping a lot of your equilibrium, you might say, in dealing with surf.

Scott Langdon [00:02:14] Hello and welcome to episode 131 of God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. I'm Scott Langdon. And today we come to you with our 15th edition of What's On Our Mind. In our series What's On Your Mind, Jerry and I read and discuss emails sent to us here to the podcast from people telling us their stories about their encounters with God. In What's On Our Mind, I get the opportunity to talk with Jerry about our own personal encounters with God and our own spiritual journeys. This week, Jerry and I talk about religious pluralism and how the phrase different strokes for different folks might not mean what it meant to me growing up. I hope you enjoy the episode. Here's Jerry.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:03:00] I was talking to-- he's the closest I know, I personally know, to a saint, Father Francis Clooney, a very distinguished scholar at Harvard, but remains a person. And I told him his scholarship was almost pastoral. And he said, "I'm glad you see that." He's not writing just to prove he's important or here are abstract things, but he's trying to help people understand ultimate matters as best he can. But anyway, just in chatting one time he said, "We're all victims of our religious childhoods." And so you start off with something that puts you in the wrong direction. You start off with the child's understanding of it, after all, which is very rigid and maybe kind of magical and so forth. What's a child to do? You're a child. You take in as you take it in. And I can remember going to my grandparents, and maybe this is mentioned in the God book, I can't remember my grandmother's church, which we would go to when we were in Memphis, Tennessee. It was Pentecostal, and they would be rolling in the aisles and talking in tongues. And our little Sunday school teacher, where you'd think you're going to little nice Bible stories and stuff, would somehow start ranting and tears flowing down her, you know, down her cheeks. And I just found it kind of scary. What on earth is going on here? It's like being in an insane asylum. And I don't mean that as a judgment, but as a child's reaction.

Scott Langdon [00:04:32] Yeah. Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:04:34] I mean, people often are having to get away from something. And I think this is somewhat different from your take on it, Scott. I think often what one needs to do is get a distance and then be able to reappropriate it without the fangs, you might say. You know, in a benign and deeper, more mature understanding. A lot of this is just magical thinking. God is what, in God: An Autobiography, God is the rescue helicopter. I think that comes up talking with Judy. No, that is not what God is, even if you have a God. And I know your feelings, Scott, which I can relate to in terms of my own childhood upbringing, is God can just turn his back on you. One of the-- I generally like the invitational hymns, they were gentle, just as I am, Lord. You know, one, I come to The. But one of them was Jesus is standing on Pilate's trial and what would you say to one of your help or something? What will you say to Jesus? What will you say to Jesus? And I am going to say yes, you know, or. And then the final verse is, yeah, I'm, when at the end of it all what's Jesus going to do with you? And, well, that's an implied threat, right? You know, you're not with him now. He's not going to be with you then. But in general, I had the benefit of not going to a fiery church. I barely remember hearing about hell. You knew you didn't want to go to hell, but it wasn't mainly a scare thing, and it wasn't mainly a magic thing. It was mainly a living your life with Jesus thing.

Scott Langdon [00:06:25] Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:06:26] And the minister was kind of scholarly, which I liked. He would tell you about verses in the New Testament, what the Greek New Testament statement was and how it was interpreted this way and that way. And of course, I loved that. He was, other congregation, members of the congregation criticized him severely because he wasn't the dynamic bringing the souls to the Lord. You know, the kind of Oral Roberts kind of crusade sort of preacher. But I thought he was a good and godly man, as far as I could tell. And so it wasn't scary. And there's not-- the beliefs -- they just never had any answer to any of the kinds of questions I would pose. They barely seemed to have a theology, but so just not my cup of tea.

Scott Langdon [00:07:17] Well, the danger, according to the evangelical tradition that I grew up in, was probably the most dangerous thing you could say. And I don't know if it's really true anymore, but the most dangerous thing you could say is "Different strokes for different folks."

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:07:33] Oh, yeah. Right, right, right, right.

Scott Langdon [00:07:36] Right? Which my grandmother, who was a Catholic, raised and then Lutheran my whole life and that was her phrase. She would say, you know, "Different strokes for different folks." And that was just super dangerous because if you could be led astray by this, that or the other. Now, that would apply to different versions of Christianity. But ho, ho, how it would apply if you tried to get in-- if I tried to read the Tao. Or if I tried to-- do you know what I mean? Like that would be even worse. Like if I were trying to get something from Buddhism. What do you do? I'll pray to Jesus for you to bring you back to the fold.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:08:20] Yeah, yeah. That.

Scott Langdon [00:08:21] And it seems like that's, you know, I was, talk about surfing, you know, I feel like I was sort of riding the wave of the tipping point for that because I don't think it's so much like that anymore. That kind of view is in the minority now, I would say.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:08:38] Yes.

Scott Langdon [00:08:38] And it has, that wave, has gotten to that crest of that tipping point. Right, it seems, around the same time that coincidentally (no) God gave you this task.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:08:50] Yeah. Yeah.

Scott Langdon [00:08:51] To say, here's a revelation about revelations. Here's what I was up to with Buddhism. Here's what I was up to with Zoroaster. Here's what I... I mean all of it.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:08:59] Yes. It's all of these. Yes.

Scott Langdon [00:09:00] So then whenever I read anything, then I go, okay, well, this what? And that's what the discernment is from here, right? So then you--.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:09:06] Yes.

Scott Langdon [00:09:06] Which is why all of these banned books and all of let's ban this and ban that and keep our children from this, that and the other, does not work for me because it's the folks with the loudest religious voice seem to me to be the ones who trust God the least.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:09:26] Right. Right.

Scott Langdon [00:09:26] Because if you think about it, if you really trust God, you will, you know, pray to be there for your children, for whatever questions or concerns they might have. And you will, you know, release your children to the world, trusting that God, in their curiosity, and they will come to you and go, "We learned about two daddies in school. What does that mean?" And you go, okay, let's sit down and talk about different things. And instead of going, Ahh, I'm freaking out, their indoctrinating, grooming, well, don't you trust God? That God will direct your child in the way they should and you will be empowered with what to say? And we're always trying to, you know, push it aside, push it aside, and we can't anymore. The information is out there. The kids, whomever, are going to find information. Well, prohibition didn't work for Adam and Eve. It's not going to work. It doesn't work that way, I feel. I mean, there are boundaries. We talked about those boundaries, creating art within, you know, boundaries and so it's the same kind of thing here. There are boundaries, but we don't trust that God will be those boundaries, I don't think. It doesn't seem.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:10:33] Yeah. Yeah. No, that's very difficult. And I understand the concern. There's the very narrow minded version of the concern which you're alluding to and someone who did a Life Wisdom episode with us, Mark Groleau, I can't remember if it comes out in that episode, that I had gotten to know him by his interviewing me about the book some time before. He grew up in a church that was some kind of Anabaptist variant, brethren of something or other, and they were anti-Trinitarian. And it was so narrow that they thought all those Trinitarians were going to hell, you know? Well, then he went off to seminary. He was very religiously inclined. And he's a great outgoing person, a great talker. So he was already doing a bit of preaching, you know, as a high school kid, and went off to seminary, which seemed like the logical thing to do. Well, reading the New Testament and everything, here's the father, here's the son, and there's kind of I'll leave the Holy Spirit with you, you know. It doesn't seem heretical. And then he ended up being a very broad minded theologian, you know, exploring trust in God and trusting of the spirit, you might say, to lead us. And that's why we often talk about the more legitimate version of their concern is different strokes for different folks just sounds like, well, if you just want to live your life as a druggie, fine. That's going to be just a wonderful way, you know, if it works for you. Well, these things, these questionable lifestyles usually do not, in fact, work for people.

Scott Langdon [00:12:23] Right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:12:24] And it's hard. But you’ve got to have some, you got to pay attention, have some sense of a normative direction to life. Some things are better than other things. And certainly health is better than sickness and so on. These norms are in some way based right in nature. And in the more delicate things of the spiritual life and religious belief, that's where spiritual discernment becomes so important. And we always just saying pay attention because there's not a rulebook for it. There's no rulebook that'll say, "Oh, well, Hinduism and Buddhism out, you know, Christianity and Judaism, out." You know, anything like that. You have to take them in with as much sympathetic-- I always think the first start as sympathetic-- understanding. You take in the various belief systems with first sympathetic understanding because you're not going to even know whether what it is you're rejecting unless first you enter into it with a kind of empathy to understand what they're saying, what they're experiencing. Why do they see the world this way, and what does that do for them? You know, what does that achieve for their life, for their culture? And, you know, Judy is an anthropologist, so she's very accustomed to going, okay, here are these Stone Age people. I think I misstated it's Borneo, it's New Guinea. But that's all part of what's current day Indonesia. And so she enters into how they see the world, the Stone Age culture. And every culture has its own integrity, purpose, hierarchies, norms and, you know, explanations for events, the whole works. And to understand the culture, you really have to enter it with deep sympathy and empathy. And Judy, as a personality, has that, and a lot of the best anthropologists do have it. I've read students of one religion, a superb anthropologist of one religion, and just as she describes it, you almost feel she's about to convert to it. You know, it's on an alien belief system, and because she does all the kinds of studies and rituals they do, you know, as if she were trying to become a priest or seer or something in that tradition. And then you can say, ah, but now from the inside, even now, and of course, being aware of many things that, especially if you're studying an ancient tribe, they may not, they're presumably not aware of, well, you can say it's got these limitations. I can, it works for these people in this way up to this point, but it's got these limitations. And okay, you draw from it what you can that's valid and gives you insights and certainly insights into human beings and human cultures. And then you appropriate the part useful for your life. And that's the valid part of the different strokes. What's useful for your life isn't the same as what's useful for your next door neighbor's life, and you need to tolerate that.

Scott Langdon [00:16:22] In episode seven that we replayed, and then you and Judy had your discussion about episode seven, there is the talk about the two things: the drop of water that you saw as a child and how you saw it in its suchness; and then later as a young adult outside the movie theater in these concentric circles that gave you the sense of time, disclosed its essence to you.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:16:55] Something like that, yeah. The image was something like swirling around, concentric circles around a center. And so when I later read T.S. Eliot, the still point of the turning world, the lines begin, oh, that was like my experience. And Eliot had a mystical side, much influenced by Hinduism, in fact, but also by Western traditions and was a Christian. But he had that insight that was what came to me in that experience. I couldn't have articulated it. You know, Eliot can write poetry out but I could barely have described it, and that's the closest I'd come, that it did seem like the essence of time. What is time? Time is one of the great mysteries of the world. You know, the idea of reality is only now. And yet the now is an infinitesimal instant. You know, the now when soon as you say now, that now, that moment is gone. You know, so this has puzzled people because we think of reality, well it's got to be permanent. Well, it is permanent also. Any moment you come to visit reality, it is now. And there it is. And yet that particular now immediately disappears. And so philosophers from Plato on, Plato called time the moving image of eternity. And that's got something going for it. That's a way to think about time.

Scott Langdon [00:18:26] Yeah, yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:18:26] But the other thinkers and poets and everybody else went in different directions because time is so puzzling, so fundamental, and yet so puzzling.

Scott Langdon [00:18:38] Well, one of the things that I was thinking about while relistening to that episode is that since I guess post-Enlightenment, I don't know, I guess maybe late 17th century, 18th century and forward when there is talk of this kind of appearance by God. See just me saying that the God is making GodSelf known in this way, it seems like a mystical experience. And that word mystical has sort of taken on a similar, not a similar meaning, but a similar type of meaning as the word myth. Right?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:19:19] Yes.

Scott Langdon [00:19:19] When you use those things, it means like a fiction or it's not quite true or it's a way to talk about it, but it's not quite true. And that kind of, any kind of language now about experience with God, we still have it and we still sort of talk about it like that. I mean, you talk about- I don't know how to articulate it, but it was the suchness. And you look that up and you see people talking about it in that way, philosophers like Immanuel Kant, talking about, you know, God in things. And yet I know when I was growing up, the worry was, you know, that we would look at something as an idol like that tree is God. And oh, I want to worship that tree or I'm going to worship this little cross instead of God itself. And instead of what that actually is, is sort of noticing the suchness in something outside of you. I don't know, that danger of the idol maybe is something that has hurt that kind of language.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:20:27] Yeah, that's a wonderful point, Scott, that I well remember from my upbringing. It's almost the theme, you might say, of the Old Testament. The dramatic development in a way of the Old Testament is precisely the invisible God before people worshiped what once you're in touch with the invisible God in the invisible form, you might say, then those look like pieces of wood and stone, and people are bowing down to those. Now, when you learn those belief systems, the Hindus, for example, when they created a shrine for, let's say, the goddess Lakshmi, they pray to Lakshmi to please grant us the wish of inhabiting this storm so that when we come here and look at you, you are looking at us. And that notion of looking is their essential mode of worship. That because the looking is not just the looking, it's an auspicious sight, I think is the way it's translated. I'm right now forgetting the standard term for it. Darshan, I guess. Darshan. The darshan is a benign, loving looking, and of course the goddess is powerful. It's not inert, you might say, but the goddess is giving some, let's say, energy, divine energy to your life. And you are doing your human side of that by gazing at the goddess. And so it's not that you're worshiping that piece of stone. That piece of stone is just a piece of stone. There's probably a factory that produces these kinds of things, but you pray to the goddess, and once the goddess accepts the, you know, location, the goddess can be many places, after all, at the same time. And the goddess will be there when you go. And the ancient Egyptians had something similar and so on around the religions there. Nobody's just worshiping a piece of rock or a piece of wood.

Scott Langdon [00:22:43] It's interesting the parallels between religion and art. And I don't even know if it's a parallel. It's how they move in, they seem to move in, the same direction together, at least in my upbringing. The very, as we've talked about this before, the beginning, the introduction to my religious experience really was my grandmother and my parents taking me to the Lutheran church. And I was an acolyte and, you know, was very involved. And one of the reasons that I loved the music, I loved the choir, I loved the organ, I loved all of the Lutheran traditional music. So Bach, Handel, and I mean all of those Baroque composers. I loved the stained glass windows. I knew God wasn't in that-- that that wasn't Jesus in that window, but when the light came through and all those colors, and it just something inside me brightened looking at it. The altar with all of its splendor. And I knew God wasn't in that altar, but it just evoked a feeling in me of wow. And then being able to be an acolyte, you know, an altar boy in the robe. And I realized I loved the ceremony and the pageantry and the, you know, the order of things. And then when we went from that to the evangelical community, where it was very much like there is nothing in the church, it's very plain. There's no, and in our tradition, there was no instrumental music either. I really liked the ceremony and the pageantry. And so where I went in high school then was I sort of had this and it seemed like a parallel track with my theater world where there was this sort of this ceremony and everything. And then my religious world, which was go to church and do things in this way. But both of those tracks, whether it was when I was in theater or if I was in the church, it was about the storytelling in the end and the ceremony. Even the Church of Christ had a ceremony, you know, even though it was unofficial and there's no creed. But everywhere you went, you know, there was announcements at the beginning you'd have a prayer and then two songs and then another prayer. And then, you know, we always kind of joked about the formality of the informality in every church of Christ that we would visit, you know. But that idea of finding God in these sort of mystical experiences, both in church, in the Lutheran church tradition and the Catholic Church tradition, and in the theater, having that same kind of experience, the feeling is the same. Experiencing the otherness in this way is not unique to the church. And I think now that we have all this technology and videos and everything else we are seeing around the world, how other people are coming into contact with God, in communion and with God personally.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:25:47] Yeah, those are wonderful contrasts you set up between the Lutheran and all that it offered to, you might say, the sensuous imagination. Even though it's right there, you're soaking it up and taking it in. And there this part of, I don't know if it happened to Christianity because of the Enlightenment, somehow the Enlightenment completely subtracted God from the world. It even subtracted the human mind from the world. The science hasn't figured out why there's consciousness or what consciousness is, and some people, some scientists, want to deny there is such a thing as consciousness, as some kind of illusion. So the illusion itself, of course, would have to be in consciousness. So, they can't figure out any way to stamp it out, you might say. In fact, everything we know, including what the scientist knows, is conscious is consciousness. But that did tend to get subtracted from the world such that now if God is going to come in or a mystical experience, it's David Hume in this period of the Enlightenment, road of unmiracles. And he says of anything that happens, you can imagine God writing, you know, in the sky, so that everybody can see I am God and I'm going to do this wonder. And you watch, and the next hour the wonder happens, you know? Hume says no matter what happens, the least plausible explanation is going to be that it's a miracle. You know, there's an exception, all the laws of nature. So you get this notion, I think that comes into science even at this period, not so much earlier, of scientific laws that are deterministic and inevitable and you can't do anything about them. And so if anything's going to happen, it's either a bizarre miracle from the outside because you've banished God from the world by this, even though even the most traditional Christian has the notion of God's omnipresence. That was always puzzling. God's outside standing as the creator of a world God created. How is that God is everywhere? Well, why not? But, here, I think something the Lutherans are taking in, when you look at stained glass windows, it's not just an aesthetic experience. It's something more like the Hindu darshan. You know, the divine is showing itself through this music, through these stained glass windows, through the ritual itself. God is showing the divine self. And here it might even help that in God: An Autobiography, there is both God is both same and other than us. Same and other than the world. And there's no bar to thinking of God as just God is literally, you might say, everywhere or the divine is, you know, not necessarily in personal forms. We don't have to always think of the personal aspect of God, which was so vibrant in my life, but that's not the end of the story. There are also aspects of God that are not personal, and they can show up all the same. Often the Catholics have this sense that they call sacramental, that you just look around and you know, everything in the world is a bit of a sacrament or, you know, a testament to the sacred. And I think there are pluses also for the Spartan Protestant church. Well, it gives you something too, I think, in terms of, I don't know, your own spiritual journey or your own direct relation. You know, all the things you describe are things we're all experiencing in common. You're all hearing the same music. You're probably singing it in a choir. You're all following the same rituals, etc.. And the glass windows, they may be stages of cross or something and they mean the same for all of you. Whereas there is this other experience that's more intensely personal, that is emphasized in the Post-Reformation period, and it gets very extreme sometimes. Well, both can get extreme. You know, the kind of empty ritualism can get extreme, but every person having their own bizarre spiritual journey can get extreme too. Maybe it's not a spiritual journey at all. Maybe it's just wandering around or taking a wild ride across the countryside. So anyway, one has to always kind of see each thing has some truth in it, but that truth may be limited. It almost by definition is limited because the other things have other aspects of the truth.

Scott Langdon [00:31:24] Thank you for listening to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. Subscribe for free today wherever you listen to your podcasts and hear a new episode every week. You can hear the complete dramatic adaptation of God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin by beginning with episode one of our podcast and listening through its conclusion with Episode 44. You can read the original true story in the book from which this podcast is adapted, God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher, available now at amazon.com, and always at godanautobiography.com. Pick up your own copy today. If you have any questions about this or any other episode, please email us at questions@godanautobiography.com, and experience the world from God's perspective as it was told to a philosopher. This is Scott Langdon. I'll see you next time.