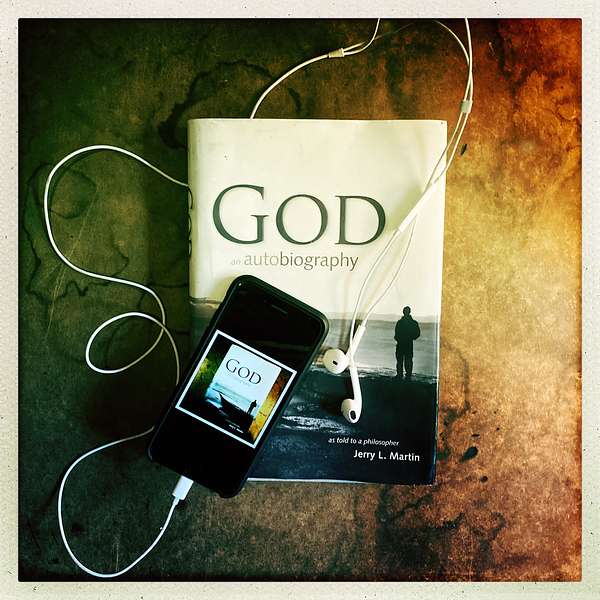

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

134. The Life Wisdom Project | The Drop Of Water, Humans, And God | Special Guest: Mark Groleau

Meet Mark Groleau, who began working in the church but was led on a mission to end boring weddings everywhere! An officiant and entrepreneur now, Mark first interviewed Jerry on his podcast WikiGod, featuring stories of Jesus-followers from all walks of life in the Toronto area.

Mark teaches his Unboring Wedding method to officiants worldwide, changing traditional ceremonies into the couple's love story. Mark is also working on a new project called 'PostBible - Ancient Gods and Ways' where he is retelling the Bible stories in a fun and accessible way - 'with a healthy degree of separation.’ Passionate about stories, Mark offers an insightful understanding of one's story and relationship with God.

In this Life Wisdom Project episode, Jerry and Mark discuss episode 8- I Experience God. Mark shares his own stories highlighting the importance of listening and paying attention to divine messages. Mark receives a divine message after hiking up a mountain that changes his perspective on everything.

Jerry and Mark talk about diversity, particularities, and process theology, while including many deep thinkers and philosophers in on the conversation. Covering empathetic understanding, love, and parenting, the two uncover whether life should include suffering.

LISTEN TO RELEVANT EPISODES- [Dramatic Adaptation] I Experience God

READ- Is God a person?

WATCH- What's Your Spiritual Autobiography with Mark Groleau

God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher, is written by Dr. Jerry L. Martin, an agnostic philosopher who heard the voice of God and recorded their conversations.

The podcast began with the Dramatic Adaptation of the book and now has several series:

- Life Wisdom Project-How to live a wiser, happier, and more meaningful life with special guests.

- From God To Jerry To You- a brand-new series calling for the attention of spiritual seekers everywhere, featuring breakthroughs, pathways, and illuminations.

- Two Philosophers Wrestle With God- sit in on a dialogue between philosophers about God and the questions we all have.

- What's On Our Mind- Connect the dots with Jerry and Scott over the most recent series episodes

- What's On Your Mind- What are readers and listeners saying? What is God s

Share Your Story | Site | Facebook | Instagram | Twitter | YouTube

Scott Langdon [00:00:17] This is God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. A dramatic adaptation and continuing discussion of the book God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin. He was a lifelong agnostic, but one day he had an occasion to pray. To his vast surprise, God answered- in words. Being a philosopher, he had a lot of questions, and God had a lot to tell him. Episode 134.

Scott Langdon [00:01:10] Hello and welcome to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast and the eighth edition of our series The Life Wisdom Project. I'm your host, Scott Langdon, and today Jerry talks with our special guest, Mark Groleau, about his take on episode eight of our podcast called I Experience God. The pair discuss Mark's spiritual journey and how Jerry's book opened up so many new possibilities about how we encounter and experience God. Mark's story is similar to mine in many ways, so it was really interesting and exciting for me to put this episode together. I think it's a fascinating conversation and I think you will too. Here now is Jerry to tell you a little bit more about Mark. I hope you enjoy the episode.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:02:00] I'm very pleased to have as my conversation partner in today's Life Wisdom Project episode, Mark Groleau. Mark was one of the first people ever to interview me when God: An Autobiography was first published. Mark had a podcast with the wonderful name WikiGod, which was quite memorable, and he was interviewing all kinds of people, mainly right there I think he was in the Toronto area, and thought to interview me and we had a wonderful conversation. It was one of the first interviews I ever did with anyone. At that point, he was not going to be a minister, exactly -- I think he does some of that still -- but he was looking for what can I do that would be valuable to people? So he and his wife thought, well, what else could they offer to people that would bring their own spiritual and humane temperaments to bear on it? And so they started Unboring! Weddings. Why not have weddings that are both fun and deeply meaningful for the people involved and their families and the community around them? Well, today, the Life Wisdom Project is on episode eight of the dramatic adaptation, and very pleased to have Mark Groleau as my partner in the Life Wisdom Project examination or takeaways from episode eight. Hello, Mark.

Mark Groleau [00:03:36] Hello, Jerry.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:03:38] And I've known Mark since he did one of the very first interviews when God: An Autobiography came out.

Mark Groleau [00:03:45] Oh, I didn't know it was one of the very first.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:03:47] It was one of the very first. And we had a great conversation that was wide ranging and sort of moments of profundity, perhaps, and certainly fun. You know, we totally enjoyed it. It kind of went on too long- one of those things, but it was a very nice outing for the book that was kind of new, and I had only talked to a few people, you know, interviewers, at that time. And the wiki-- that was on your podcast, WikiGod, as I recall, you had recently gotten out of seminary- graduated.

Mark Groleau [00:04:23] Yes.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:04:24] They kind of set you up with this. They let you do this for a time.

Mark Groleau [00:04:29] That's right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:04:30] You were interviewing all kinds of interesting people. A lot of professors of theology, biblical scholars and so forth. And then you saw God: An Autobiography-- well, let's talk to this guy.

Mark Groleau [00:04:42] More specifically than that, it was a-- so I was doing WikiGod as a podcast. And again, anybody and their cousin can have a podcast about anything. It was a Christian radio station in Toronto that had picked up my podcast and started kind of syndicating it on their channel. And then they were kind of recommending to me-- I mean, it had only been a few weeks of them doing this, where the producer of the station said to me, "You know, we get solicitations from people who want to come on, etc., etc.." Again, it was kind of conservativey Christian, so already a bit outside of my scope, but they gave me your book and said, there's this guy / heretic, Jerry Martin, he wrote this book. And I said, "Well, see, the WikiGod thing was only Toronto." That was my big thing. I only wanted to interview Torontonians. That's where I lived. I wanted it to have that local feel, you know, head of the young street mission, people who are doing exciting social activism in the city. I wanted people to feel like they get to know Torontonians through my podcast. So right away I was like, I don't think I'm going to do this. He doesn't meet the qualification. He's not from Toronto. But it was when I got my book, your book, in my hands that I started reading it. I was like, okay, this is a whole different-- I think I'm willing to make an exception here. Because I was in a bit of an existential, I don't like to say crisis, I would say awakening because it was such a pivotal turning point for me where I, you know, I was leaving the denomination because I wasn't in step with it. I was struggling being associated with like a more conservative or evangelical Christian radio station. We went ahead with it. We talked like you say, it's still one of my favorite, most memorable episodes. I love your book. I brought it down again because I still have it from this is a few years ago, and the part we're talking about today, I was flipping through, I found it in the book. And there were very, I don't want to say few, but there were select pages where I had, you know, circled the number and just defaced the page. And the passage that you want to discuss today was one of those very circled and defaced pages, which I found very interesting. Like, oh, wow, you know, this was what, 2015 or 16? And I just-- I was going through something at that time where not just your whole book was really pertinent to my processing, but also that page, the idea of subject, object, I/Thou. I was reading, you know, Buber and Miroslav Volf and struggling through issues of, you know, my church upbringing, and it was all coming to a head. And it just kind of, like, your book was just this bursting point. Life changed a lot since we've had that conversation and you're partially to blame.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:07:44] Well, I take credit. I don't take credit.

Mark Groleau [00:07:48] Good.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:07:48] I'm just the pen in God's hand.

Mark Groleau [00:07:50] Yeah. No. Yep.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:07:53] But, what did you make of this?

Mark Groleau [00:07:55] Well, and that's what's interesting about book endings. You know, it's not just an anecdote of going back to 2016 and seeing how much I marked that page up. Right? Like, when I look at it now, I think I just take for granted living the way that a lot of the points you make / God makes in that section of the book. Like I said, I just, to me, that's kind of like breathing now. But in 2015, 2016, it was mind blowing. And like I say, I had just kind of been in touch with Miroslav Volf as I was graduating seminary, got my M.Div., they didn't focus a lot on that, so I was reading it in my own time. Specifically stuff around the Trinity, which yes, is this uniquely Christian doctrine and concept. I say concept now because I grew up in Oneness Pentecostalism, which if you were to put kind of what you wrote in that book and one that's Pentecostalism on a continuum, I would say they'd be at like polar opposite ends of the spectrum in the sense of, if you know of one, that's Pentecostalism, it's very much about division. There is profane and there is sacred. There is God, and then there is everything else. God is removed; God is outside; God is Wholly Other-- capital W, capital O - God is Singular - capital S - there's no plurality. So of course the Trinity is a heresy for in that view, and so I came out of that, became an atheist, then went to seminary, kind of tried to rebuild. You know, you're in the Christian kind of more mainstream Christian bubble in seminary. And I had to kind of reconstruct like, how does the Trinity make sense? You know, you can go the Athanasius way, which I did at first, then you can start looking into kind of Buber, I/Thou, and Miroslav Volf with the Perichoresis idea was really, you know, mind blowing for me, this idea of Father, Son, Holy Spirit in this dance, exchanging places, differentiated, they need the individuality and yet always trading places for each other. So it's this hyper hospitality in the person of God, which of course opens up the table for the rest of creation and humans to join in in that dance as well. So that was all swirling in my head and I was reading that kind of thing when I picked up your book and, you know, in just very conversational vernacular, which is what your book does so well. Hey, God, I don't know about this, this is weird," kind of replying back. And that's why it was striking such a chord of all that, I don't know, lofty theological terms and things like that, just in a very easy to digest conversational way where, like I say, growing up, where there's sacred and profane, very dualistic--.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:11:00] Yeah. Yeah.

Mark Groleau [00:11:01] And so you go from dualistic to, oh my gosh, everything's connected. That's where then I kind of– I had great sympathy for like, the panentheistic view where God is in everything. So when you get to the drop of water, I'm in there. You're in me. It's very, you know, gospel of John, if you're familiar with that language, which again, some Christians don't know what to do with that. I see the gospel of John as, you know, something crazy is going on there, like, you know, mystical, dropping acid kind of stuff. But it is that. There's I am in you, and you're in me, and they're in you. And so this is a long way of answering your question and saying, when I move through the world and I have dispensed of the duality and this idea of I am subject, everything is object, or God is subject and I am mere object, it really does change how you see everything and I believe move in the world.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:12:03] Yeah, well, it concretely, how do you just take a day? How does one-- how is one's day different when you live in terms of the plurality and diversity of things that are particularities. Well you know that opening quote from T.S. Eliot.

Mark Groleau [00:12:25] Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:12:26] Without the still point, sounds like God or the deepest meaning in life or something without the still point. There is no dance, no movement. No diversity.

Mark Groleau [00:12:37] Right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:12:38] And then the odd thing, that's the still point, sounds like everything, but then He goes on and says, "But there is only the dance." So whatever these ultimate meanings are, it sounds as if, well, like the drop of water, they're radiated through the dance, through the movements of life, the particularities, the diversities, the people and things we encounter, the things we do.

Mark Groleau [00:13:04] And you get shades of this. Like I had a professor in seminary, Howard Snyder, who was the Wesley chair, and he wrote a book- In Christ all Things Cohere. It's a very small little book, but you get shades of this in Paul, every now and then, where it's like he was on to something but maybe didn't take it far enough. That idea of like in Christ in your book you would say kind of the Bodhisattva, if I'm saying that correctly, you know, that idea in Christ, that is the glue, that essence, that substance/essence of Christ is what infuses all things like you say. I remember when I was reading because I'm super into process theology, I don't know if you're aware of that.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:13:49] Yeah, yeah.

Mark Groleau [00:13:49] Whitehead and John Cobb. And when I was just wrapping my head around this again around this, again, around that time, 2016ish, I was at the cottage reading John Cobb's book, an introductory expository on process theology or something (Process Theology: An Introductory Exposition). You know, you're sitting by the lake and you're looking at the hills and the trees and there's not much there but nature. And again, coming out of this idea that, you know, humans are just the be all end all of creation, God was sitting around doing nothing, just bored out of His or Her skull until we arrived. Process theology, you know, there's so much to unpack here, but God loves like God can do-- God can do nothing but love. And almost in the way that, you know, the wind can do nothing but blow. This sense where every single moment is pregnant with potential for every single molecule in the world, and God loved every single thing in the 14 billion years, as far as we know, since the Big Bang. It just-- I remember sitting on the lake and looking up and seeing the lake and the trees completely differently. It was-- it did feel sort of like a mystical experience, many of the kind that you describe in your book where I said, okay, that like hunk of rock that now has trees on it and stuff, whatever that was 4 million years ago, I mean, God loved that no less than God loves me right now or, you know, my one year old child. Now, the capacity -- my capacity to -- I have more capacity perhaps than a mountain just with my arms and legs and brain and things like that. But God is this great loving force or call like a magnet that is pulling everything forward. And that's true of the mountain, the drop of water, every little molecule in the drop of water and me. And so it's not this sense that like God was waiting around until, you know, finally Homo sapiens stood up or something like that. But I just saw the whole cosmos, the world around me, infused with love and with God that, like I say, I think since then I've just moved through the world with that as an assumption. Whereas, and this is where just insights like that, they really do- it's not just an intellectual exercise, insights like that really do change the way you live because they change the way you see the world and therefore they affect your capacity for compassion and love and things like that. So that was a moment where, again, I felt the fuzing I just felt that moment you describe with the drop of water and I feel like I had that beside a lake reading John Cobb.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:16:46] Yes, yes. Well, these come at unexpected moments. And one of the things I'm often telling people is pay attention. I have got a friend who, I may have reported this in the book, I can't remember, she went up the Amazon. She's a great environmentalist. Not.

Mark Groleau [00:17:03] Yeah, it's in the same-- It's in the same chapter as this passage, I think. Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:17:07] Oh, is that right?

Mark Groleau [00:17:08] It's pretty close.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:17:09] Yeah. And she went and had, going up, they were riding up the Amazon and she was restless and went up above the boat and the starry skies, everything darker than you've ever imagined. No city lights and the only sounds, the murmurs of the jungle, other than that total silence. And, you know, it was just an extraordinary moment where you take in something about the meaning of it all, that you don't then articulate. But it's just, wow! I kind of saw something. And I told her, "Go write that down," because otherwise you'll put it in the mental attic. You won't pay attention because it doesn't fit anything else you're doing in your daily life, you know, as you see it, it doesn't help achieve any of your targeted goals that you pin up on your to do list for the day. But it's a very important aspect of life. And so you need to not just live a utilitarian, pragmatic mode, but you need to be taking in the ramifications, details, depths of experience, experiences deep. It's not just superficial, like images on the screen. There's a kind of depth there that you can encounter and it's going to be different from one person to another. And what are the more meaningful moments? And it can be, you know, a drop of water is the least pre-processing thing you can imagine, I suppose. But more often it's something of beauty or striking, so it gets your attention. But it need not be. It could be when we were going to have an illustration for this kind of theme, I said, I don't want some beautiful grandeurs, you know, the Grand Canyon or-- I want, let's have just a little rather ugly, unprepossessing frog in the mud, you know? Okay. Because whatever-- a lot of people don't like the word God, of course, in light of my experience, it's a very lively word. But if you don't like it, just look for the meaning of things. What are the things that have the beauty, the other values things have and just be alert to them. Take, you know, take them in as you go about your daily life.

Mark Groleau [00:19:44] In my capacity I tell love stories. I'm a wedding officiant, and every couple I tell a love story. So I tend to think of things as stories. I've got this project now where I'm reinterpreting the Bible and its stories. I have two kids, eight and ten, and they've been addicted to stories their whole life, as we all are as human beings. But just, I mean, it's profound when you make the shift of understanding subject and object, right, instead of everything being the object to me, the subject, even if you don't wrap your head fully around Buber and all that stuff, I think you know the new story you bring to every circumstance, whether it's a frog in the mud or another person in front of you of approaching it or telling yourself the story that, okay, I am -- it's almost like you can step outside yourself -- I am the object, quote unquote, to this person. It allows you to transcend yourself for a moment, Although, you know, I'm hopelessly postmodern in the sense of I know you can't fully transcend your own experience, but the awareness, I think, of saying, you know, of regarding this person in front of you, not as an object, but as the hero of their own story. And I am-- they are approaching me right now as opposed to me approaching them. It's almost like, you know, a movie camera, you can kind of hop up and see yourself approaching their space. I think, again, that has huge implications for just how you treat your neighbor, your capacity for empathy and compassion. And that is not something that I would take for granted. I hadn't encountered that until my thirties, just to think about myself as entering other people's stories, myself as object. I know we don't want to preserve those, you know, dualistic distinctions, but the distinction is important as the reading that we're talking about here, you need that differentiation in order to be distinct. But they're also I mean, that's what makes union possible. And so this is to me how it has affected how I move in the world and regard others. I'm not the center of the universe. Imagine that.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:22:03] Yeah, I think one of our great human capacities, and it's at least in things I've read in life, it's not very often highlighted, though you just now use the word Mark, which is empathy. You know, you have-- it's kind of remarkable because if you think of standard, you know, I alway worked on the mind body problem. How do I inside here, inside the subjective flow of my experience, a classic modern philosophical problem. How do I even have the idea that someone else has their flow of experience? But the fact is that we do have this capacity that we can engage another person and it might need to be cultivated a little, but it's somewhat natural to us, that we can sort of enter into, we can imagine, we can somewhat imagine what it's like to be them. What is it like to be there to go through that? I read the news and Ukraine. Okay. I can imagine what it's like to have the side of your building blown away so that your living room mouth faces out onto the park, you know? Okay, we can imagine these different kinds of experiences people go through. And you're quite right, Mark, and it's a very useful concept. We were just talking over breakfast with my wife. I had a friend who'd say it's important to be the hero of your own story. The hero, not in a heroic sense, but the protagonist, the leading character, you know, your living, your self.

Mark Groleau [00:23:34] And I think that rolls off the tongue because I'm obviously a marketer for my business. But Donald Miller, you know, who wrote Blue like Jazz and that, he is now kind of a marketing guru and that's really important when you're a marketer is to see your customer as the hero and you know, you're the Yoda. So you're not-- when you're writing a sales page because I'm inside marketing baseball here, but it's been so helpful and kind of come natural to me where you don't say all the things I'm going to do for you if you buy my thing. You talk to the person and say, for in my case, you are going to officiate this wedding, you're going to crush it, you're going to blow people away. People are going to laugh. People are going to cry. Your couple's going to be the happiest they've ever been. Everyone's going to say it's the greatest thing they've ever seen. You did that. You're the Luke Skywalker. I'm Yoda. You know, you're the one who's going to blow everybody away and bring down the empire. And I am just kind of whispering in your ear, so, yeah, that's that piece.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:24:32] You can do it.

Mark Groleau [00:24:33] Yeah, exactly. So even from that, it's important, you know, but going back to empathy, I mean, a lot of parenting has happened since we last talked on my side. And my wife and I really decided perhaps you know, more her because she's a marriage and family therapist, but, you know, a lot of this theological stuff and thinking that I've been doing, we read a book by Alfie Kohn called Unconditional Parenting when we were really like figuring out what's our way of doing this. And the philosophy behind that is not to punish and reward kids. Don't make them not want to do bad because they're going to get punished. Don't make them want to do good because they'll get a reward. Well, then what do you do? And basically what you do is kind of intrinsically teach them all along the way, kind of what you said there about like our capacity to consider others in our actions. So now our kids are eight and ten. We always said like, you know, we'll see how this turns out. I'm pretty confident now. I think we did a good job. They were never rewarded for doing something. They were never, never punished for doing something that's of go to your room, or no dessert. What we would do is intrinsically talk to them about empathy, you know. So like, you know, when one of your kids slaps another kid in the head in daycare, you really, you don't just punish the kid and say, no, you sit down and you teach them the effect that that action had on the other child, on the parents. You know, the parents would have been scared, etc., etc.. And that's just one example. So you multiply that by 100 incidents around the house, around their friends at school. And I believe that what happened is we really amplified their capacity to empathize in the sense of I'm an agent of my own actions. It's funny because in my post Bible project, I unpack Genesis and Adam and Eve and Cain, and I believe that that story is talking about the same thing. The agency you have now as a human is to club somebody upside the head with a rock, but here's why you don't want to do that necessarily. Right? And so, I mean, we're doing this with our little kids and now they are so empathetic. They really do think about the other person in front of them. I think, you know, they're not using this kind of subject object thinking, but, you know, as them, I'm entering into this person's experience, what effect am I going to have? I just think like, you know, if more people approached each other in the world that way, perhaps the planet would be a lot healthier in a lot of ways.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:27:22] Well, one thing, one of the roles of empathy is simply understanding each other in just a normal conversation.

Mark Groleau [00:27:28] Right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:27:28] The words coming out of my mouth, what do they mean to Mark? And to just kind of watch, and you're trying to use your language carefully, if you pay attention, so it's not heard the wrong way, you know.

Mark Groleau [00:27:45] Right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:27:45] So I pay attention to where somebody is coming from, what their background is, what this vocabulary means to that person. That's one reason I'm often careful about the God word. Because it's a very rich meaning word to me, from my experience, but it means different people to different times.

Mark Groleau [00:28:06] Yeah, absolutely.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:28:07] Scott Langdon, our host, was going through a time when the theistic language was a burden to him, it didn't work well, it was causing problems. And so he said, "I gave up God for Lent that year." And what he did was substitute the word love. Imagine in the beginning, love created the heavens...

Mark Groleau [00:28:30] I love that. Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:28:33] One of the words in the prologue to John in the beginning was the love and the love was with God, and the love was God. You know, so it's a very interesting experiment. It's not unlike what you're doing with the stories where you see what you can learn by an imaginative reconstrual or play.

Mark Groleau [00:28:56] Well, it's funny that I mean, just as we zoom in on that word, because one of the things that I do, especially with my kids, is I always substitute the name of God, I understand for Jewish folks, that might be a challenge, but I love looking at the Hebrew translation and seeing how in the first chapter of Genesis, the word is Elohim instead of God. Like that's the word for the deity there. And then in the second chapter, totally different creation story, it's now Yahweh Elohim, which is completely different. And then by the time you get to chapter four, Cain, suddenly it's just Yahweh, not the other two. And so I like to again, use the names that we don't see in English, or we just put the word God in. And for me, I think it's a bit problematic because, like you say, when we say God or I prayed to God this morning, but then you read God back into Genesis, I guess you would just presuppose that that's the same God or that's my God. And I don't think it allows for the evolution of God, the kind of thing that we read about in your book, understanding that perhaps God has come a long way since that God, or even that the people who wrote the stories in the Hebrew Bible had a completely different conceptualization of God. So, for example, when I read these stories to my kids like Moses or whatever, I will say Moses is God instead of God. I'll just, this is one of the ways that I edited children's Bibles. Every time I picked up a children's Bible with my kids as they grew up, I never, I was never happy with what I was reading. I would edit on the fly. And so that was just one of the things where I don't want to say like, you know, God told Moses, I would say, you know, Moses' God said to Moses, blah, blah, because I just feel like I do think it's important to have a sense that your conception of God is quite subjective. I think, you know, like you say, one person is offended, one person is not, one person you know, this whole like God, the Father. Okay, so God, the Parent. And there's no way we're all thinking the same thing when we say God. So I think language should reflect that. And I even think biblical language should make room for that when we read the Bible.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:31:08] You know? Yeah, that's important to realize these - the key terms - and we're using God as our key term, but things bandied about in political debate, for example, justice, well, there are many conceptions of justice. And one person--.

Mark Groleau [00:31:23] Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:31:23] You know, they're arguing as if they both had one univocal concept. But who knows what their strict definitions are and who knows what the connotations, the other emotional associations that come from our lives, and so forth.

Mark Groleau [00:31:39] Right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:31:40] And back to the empathy point, you need to be sensitive of that, you also have to be, to kind of handle the diversity of the world, which includes for us front and foremost, the diversity of people, have to understand that there are a lot of different people coming from different places, not only just different points of view intellectually, which you can kind of map out on an intellectual map, but totally different life experiences, totally different locations, totally different things that resonate with them. And so you, in your, here, we're focusing on the language you use, but it's everything. It's the gesture. You know, do you hug them or not hug them? How is a hug going to be interpreted?

Mark Groleau [00:32:25] Yeah, yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:32:26] So all of these moves we make in interaction with one another and you also have to-- I guess the empathy includes what does this person need to hear? Not just I was going to say this now, how should I say it? But maybe I should first be thinking, what is the person I'm talking to need today or need from me? Maybe they need something else from somebody else.

Mark Groleau [00:32:56] Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:32:57] Or from me on a different day. Something different from me. But anyway, think about the dynamics of those relationships and sort of appreciate them. You know, they're not just obstacles or problems, but this is part of the richness of the lives we live. And it's good to not only notice that for these somewhat functional reasons I've been talking about, but to appreciate them, to take in the beauty of them and the marvel of them. You know, it's wonderful that people have different experiences and different ways of thinking, different ways of taking things. And all of this, one way to put a lot of, you know, this story of this episode is a kind of appreciation, you know, just take in the appreciation of beauty, the appreciation of the drop of water, the appreciation not just of the beautiful things as beautiful, but of the other things as well as you say, Mark. God was loving them all for plenty of time.

Mark Groleau [00:34:00] Yeah. I went to Colorado, ironically, to a conference around the time that I interviewed you. Hugh Halter, bi-vocational conference about, you know, ministers who need to get a job and support themselves and that kind of thing. So I was there in a very pastoral capacity as a potential church planter, etc., But I went for a hike in the mountains in Colorado all alone up on this-- it was so high, it was almost glacier-like. And I get to the top and I remember just looking out, and it was one of those like voices, because right now, at that time, I was so full of angst. I had gone through seminary. I had been a pastor for a few years, realized it wasn't for me. Who am I? My goodness, I feel more entrepreneurial than pastoral. What does that mean? Am I a bad person because I don't like holding people's hands at the hospital bed, etc., etc.. And that was kind of all the angst and let alone the theological intellectual stuff that we just talked about. And I got to the top of this thing, and I just looked out. It was this peak in Colorado, and it just felt like one of those thunder crack, obviously it wasn't, but, a voice that said, "This is my world. Just go play in it.".

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:35:13] Right.

Mark Groleau [00:35:13] And that is such a weird, it's such a weird thought to have. And I know you're no stranger to these very few mystical moments I had because we talk a lot about my barbecue incident back then when I was driving to buy a barbecue. And I just felt don't buy a barbecue. And I literally turned around and drove home and I couldn't understand it because I had saved up so much--

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:35:37] Yeah! You looked forward to it, you were all set for it. You had the money in your pocket--

Mark Groleau [00:35:38] Yeah. Oh, yeah. I couldn't wait to have the Weber like, I just knew which one I wanted. And just one of those things where you're like, I just feel like I can't do it. I shouldn't do it. And so you can speculate why and all that, but this is one of those moments. But it was just so pivotal because I came off the mountain. It sounds very Moses-like, not to bring anything to the people, but just it was like it was almost like survivor guilt. Like, can I really just, like, find what I'm good at and play in the world? Is that really okay? Is that something God would actually be okay with? And but it ended up really being a true north that yeah, perhaps that is what everyone you know, could be doing best. The best version of themselves. That's again, that's obviously not, I mean you're not doing that to the detriment of looking out for others and the compassion, and caring, and all that stuff. Because for me, again, having to come to grips with I've been to seminary, I was a minister, I was a church worky- work churchy kind of person-- And now I'm just going to be, what, a filthy capitalist businessman? But that, again, is like the sacred secular kind of divide stuff where that weird moment of hearing something that felt like it was completely outside myself gave me permission to literally come off the mountain and say, "Okay, I think I want to-- I know what I'm good at, and I think I can just go ahead and have fun with it." And it did change my life. But there is that sense of like, is this okay or is life supposed to be-- are we supposed to be suffering all the time?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:37:19] Right, right! No, it doesn't need to all be struggle. That was a wonderful, beautiful moment. Mark. And I am struck even back to the barbecue. You turned around and went home?

Mark Groleau [00:37:34] Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:37:35] I mean, you pay attention. That's what they call paying attention.

Mark Groleau [00:37:38] Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:37:38] So, I believe you have to trust these moments. You trusted the guidance- don't buy the barbecue even though.

Mark Groleau [00:37:46] So much logic.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:37:47] Whatsoever, right?

Mark Groleau [00:37:48] Yeah. Like. So much logic can come in and say this makes no sense to not do it. But, it is a level of I don't know what that is, call it God back to that point, call it whatever, but just I feel like if I proceed after hearing that it's some sort of violation. It's some sort of boundary cross that I shouldn't have, you know, that I shouldn't have done. It's funny because a couple of years after that, just next to the house where we live, there was, you know, those big, tall garbage dispensers. I had recently taken apart an old trampoline and a whole bunch of posts were sticking up out of this garbage dispenser, just like poles, like almost porcupine quills. The lid wouldn't close. So it was kind of open, and I just kept them in there. Garbage day was coming in a week or something. Well, one day, you know, after a few days after I'd done that, I'm walking by and I just said I just felt/heard- take those out and lay them on the ground. And I just thought, okay, like, why? But I did it. I took them all out, something like 14 rusty poles and put them on the ground, laid them down and closed the lid properly. Two days later, I'm washing the dishes at my sink and I see a streak go past the window and I hear a bang and I look outside. I was like what was that? And it was my four year old daughter. She had fallen out the window on top of this garbage dispenser where just two days before basically all these polls were sticking straight up. And I mean, I get goosebumps and chills just thinking about what-- how that story might have ended if I hadn't listened. Again, no logic to it, but I just felt this overbearing sense of move those. So what do you do with that? I don't personally believe it's a process guy that God can see the future or whatever, and you know, I get offended a bit when people, you know, some of my more conservative family members were like, God saved her. And it's like, well, you know, but, you know, 10,000 children are going to die today in various accidents. I don't-- that's not my theology. But there was something about me feeling that I needed to do that, that two days later was very relevant. She bounced off this garbage thing. The lid was closed. We took her to the hospital, but the doctor said she's completely fine. She got the wind knocked out of her, but that-- it wouldn't have ended that way if those polls were there. So those are moments where, like, it's happened enough times and by enough I mean maybe six in my entire life.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:40:27] Yeah. But six is a lot.

Mark Groleau [00:40:28] Where you just walk through the world maybe saying, "I think I need to be sensitive to those strange moments."

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:40:36] Well, they are strange. Jung would call them synchronicities when oh, where there's just a concatenation of events, such that one is tempted to call them a miracle.

Mark Groleau [00:40:47] Yes.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:40:48] But they're certainly meaningful in a particular way. And you just got to connect the dots. The dots are there begging to be connected in this way. And so, I guess my own attitude, since I'm not big on the concept of miracles, is, well, just take it in. You know, you don't need to think, how did this happen? Does God see the future? You don't need to go into all of that. Just take it in. Wow. And maybe take it in gratefully. Appreciatively. Gratefully. Wow, this is wonderful, you know.

Mark Groleau [00:41:25] And I'm inherently resistant to it now because of my upbringing, like a very like, you know, charismatic Pentecostal upbringing. But I think what I didn't like most about that, because obviously I still have a little bit of, I don't know, logical charismatic, but it was the formula rising of it, right? Like you needed to say the right words or you needed to walk in this way or be considered a righteous people or be a tongue talker or something, something. It was very formulaic when God would work, when God wouldn't, who God would move for or speak to or not speak to. And that is one thing, like I say, the change and the kind of passage we're talking about, if we're still talking about that, this has been such a meandering conversation, but God in everything and everything in God, and that almost, to use your water analogy, like ripples underwater or sound waves underwater, perhaps you know something about when those things were sticking up out of the garbage or the barbecue or who knows what, you get, you catch the sound wave. You feel it, you pay attention to it. And I guess what I don't-- what I resist is this idea that I'm more worthy or more spiritual or more sensitive than anyone else. I like to think that this is more of a common human-God union experience everywhere in the world. Because I think it's important to remember that no world religion, for example, has the market cornered on this. You know, everybody of every faith, people who are more mystical, more secular, like you say, there are these moments that happen to all of us as humans. It might just be the degree to which we don't push the-- suspend their logic and actually listen to the thing even when it makes no sense.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:43:18] Yeah, yeah. You start off listening and paying close attention. It's not always a voice or anything resembling a voice. Pay close attention. You know, what are the signals you might say in my life? Is something pointing me, too? And sometimes the signals are internal. It might be feeling drawn. Some of the things you talked about today, Mark, where things are more you're feeling drawn in a direction, you know, and you have the sense standing at this beautiful scene, looking down at the world beneath the mountains, and that's your playground. One of the thoughts I had, as you were describing that, Mark, is you want to do what's your assignment in life. You don't want to do the next person's assignment. And it's not necessarily I think in terms of assignment because of my particular kind of relation to God, but it's just what fits you. What fits you. And I've read psychologists say, you know what fits you when you find yourself having more energy after you do it then you had going in. If it's draining, then it's probably not right for you.

Mark Groleau [00:44:33] Right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:44:35] But if you do that and wow, now I'm really, you know, systems are flowing and--

Mark Groleau [00:44:44] Well, that's what I had such a hard time with as I was leaving, you know, full time church work. I said, this is good. This is noble. I'm trained for it. I can do it. Why? I just couldn't. Why can't I do it?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:44:59] Yeah, exactly.

Mark Groleau [00:44:59] And it really did come to that. Like the one on one meetings and the like, I just, that would just wipe me out. I would dread it going in. I didn't like it coming out. And so, you know, how do you explain that? You know?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:45:12] And so we would talk about pay attention a lot is just paying attention to what's going on inside you. Often, especially where we have certain ideas that are like norms for us, these are the rules. This is what I'm supposed to be thinking. You know, you don't know quite where you got them, maybe you were raised with them or something, or they're expectations of parents often. And you just keep living your whole life to meet those expectations.

Mark Groleau [00:45:35] Yeah. Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:45:37] So pay attention to what's going on inside you, and always be in touch with that at the same time. And you know, I'm told somewhere in the book, God says, "You should love yourself the way I love you, and then you'll be able to serve yourself better." Because none of that has to do as we all know, with being perfect. None of us is perfect. But God's love doesn't depend on that. It's not, you know, it's in that sense, unconditional like a parent. Your kids aren't perfect. They get into trouble, one thing and another, but that doesn't lessen-- you love them. You love them nonstop. And you need to love yourself that way.

Mark Groleau [00:46:19] Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:46:19] And just as with your kids, loving them effectively means you got to pay attention to their needs and feelings and stage of development and so forth.

Mark Groleau [00:46:29] Right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:46:30] You got to do that for yourself as well, don't you think?

Scott Langdon [00:46:45] Thank you for listening to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. Subscribe for free today wherever you listen to your podcasts and hear a new episode every week. You can hear the complete dramatic adaptation of God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin by beginning with episode one of our podcast and listening through its conclusion with Episode 44. You can read the original true story in the book from which this podcast is adapted, God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher, available now at amazon.com, and always at godanautobiography.com. Pick up your own copy today. If you have any questions about this or any other episode, please email us at questions@godanautobiography.com, and experience the world from God's perspective as it was told to a philosopher. This is Scott Langdon. I'll see you next time.