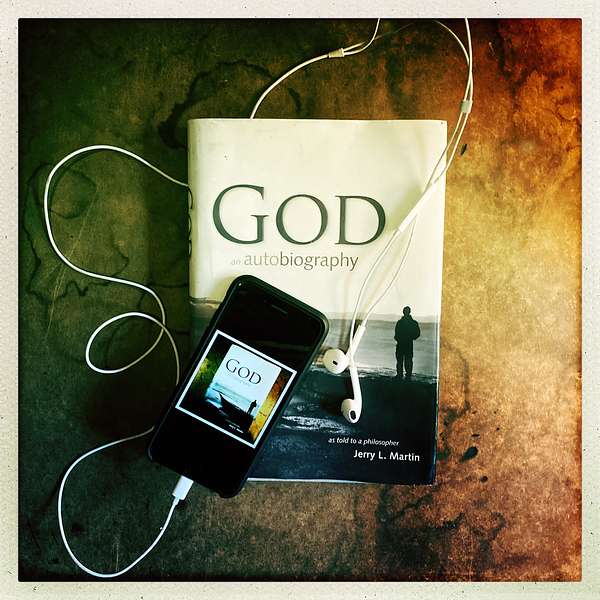

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

170. The Life Wisdom Project | Insights from Hasidic Tradition and Philosophical Ethics | Special Guest: Dr. Michael Poliakoff

Join God: An Autobiography, The Podcast for profound discussions on spirituality, philosophy, and human connection. This Life Wisdom Project explores the fascinating intersection of Jewish wisdom, erotic energy, and the Yetzer Harah (evil urge).

Dr. Jerry L. Martin and Dr. Michael Poliakoff engage in thought-provoking dialogue, drawing insights from Jewish scholars like Martin Buber and exploring sanctifying the ordinary in daily life.

From discussing the divine implications of the Yetzer Harah to examining the ethical teachings of Emmanuel Levinas, this episode offers a rich source of ideas for listeners interested in exploring the deeper dimensions of human existence. The conversation spans from ancient Greek philosophy to modern-day Jewish ethics, highlighting the enduring relevance of age-old wisdom in navigating the complexities of contemporary life.

Unpack the significance of integrating the shadow self, embracing imperfection, and building institutions guided by reason and reverence. Whether seeking spiritual guidance, philosophical insights, or practical wisdom for everyday living, this episode explores timeless truths and ethical principles.

Dr. Michael Poliakoff is the president of the American Council of Trustees and Alumni (ACTA), known for his extensive experience in academia and public service. With a background in classical studies, he has held prestigious teaching positions and received awards for his educational contributions.

Relevant Episodes:

- [Dramatic Adaptation] A New Journey Begins

Other Series:

- Life Wisdom Project- How to live a wiser, happier, and more meaningful life with special guests.

- From God To Jerry To You- A series calling for the attention of spiritual seekers everywhere, featuring breakthroughs, pathways, and illuminations.

- Two Philosophers Wrestle With God- Sit in on a dialogue between philosophers about God and the questions we all have.

- What's On Our Mind- Connect the dots with Jerry and Scott over the most recent series of episodes.

- What's On Your Mind- What are readers and listeners saying? What is God saying?

Resources:

- READ: "Pure being is not an abstraction but a living force."

- THE LIFE WISDOM PROJECT PLAYLIST

Hashtags: #lifewisdomproject #godanautobiography #experiencegod

Share your story or experience with God! We'd love to hear from you! 🎙️

Share Your Story | Site | Facebook | Instagram | Twitter | YouTube

170. The Life Wisdom Project | Insights from Hasidic Tradition and Philosophical Ethics | Special Guest: Dr. Michael Poliakoff

Scott Langdon 00:17: This is God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. A dramatic adaptation and continuing discussion of the book God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin. He was a lifelong agnostic, but one day he had an occasion to pray. To his vast surprise, God answered- in words. Being a philosopher, he had a lot of questions, and God had a lot to tell him. Welcome to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast.

Scott Langdon 01:09: I'm Scott Langdon, and today Jerry speaks with his longtime friend, Dr. Michael Poliakoff about episode 15. A New Journey Begins for this, our latest edition of The Life Wisdom Project. It's in episode 15 that God says to Jerry pure being is not an abstraction but a living force focused personally. In many ways, that understanding is at the heart of what God wants us to know and has always wanted us to understand throughout the course of humanity's development. In today's episode, Jerry and Michael talk about some of the ways in which God struggles with us in our development as we deal with, among other things, what is sometimes called the evil urge. Here now is Jerry to tell you a little bit more about Michael. I hope you enjoy the episode.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 02:04: Episode 15 seems to me a very rich episode, and so I called on my long-term friend, Dr. Michael Poliakoff, to discuss it with me. Michael is a Jewish scholar learned in his own tradition, but also a professor of classics and, in particular, someone who engages stoic wisdom, what he calls the wisdom of the middle stoa. In this episode, some Jewish themes come large into God's story. I've been reading Martin Buber and about his own religious experiences, some key concepts came up that I wanted Michael to help me think through. I do want to thank you, Michael Poliakoff, for engaging in this life wisdom discussion of episode 15.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 02:59: I think there are some interesting things in this episode. One thing let me just start here, because as I listened to this again and reread the transcript, I found that the center of the whole thing is the evil urge. Here's one sentence. It's me restating what Buber was saying, “To achieve wholeness as a person,” he said, “it is necessary to direct the creative force of the evil urge.” I can read the rest later, but I think it would be useful. This is a Jewish concept, as I understand it, and you're Jewish as well as a classical scholar and have stoic wisdom and no doubt, many other sources of insight. It is a Jewish concept and unfamiliar to many, many people.

Dr. Michael Poliakoff 03:56: Thank you for asking that question. Of course, within the compass of your book, your conversations with God, it is so important. One of the reasons I so cherish the God book is that it gives us a God who is, of course, the God of holiness, a Kodesh Boruch, the Holy One, blessed be He, but also a God with empathy who understands His creation. The Yetzer Harah, the evil impulse is, of course, part of that creative power of the world. It aligns nicely with another concept, which is that we try to make everything in our lives holy. Eating can be what animals do. Our table can be a trough or it can be an altar where we worship God, we thank God, we commune with God.

Dr. Michael Poliakoff 05:05: In fact, that was one of the brilliant aspects of our Talmudic rabbis. I know I'm going off in a little tangent here. What kind of religion would we have that was temple-based that could no longer be so? The temple was destroyed, so many of the house of Israel were in exile. What would save Judaism? What would save God's burden, the duties that He gave to us? It was to make every person an efficient, every person responsible for the holy service. Hence the table is an altar, and I really do love what the Hasidim tell us about sanctification.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 05:59: That was another thing I was going to ask, because Buber says, and that you can help us understand, this is a quote from Buber, from Martin Buber, the great Jewish scholar and thinker, “Overpowered, in an instant, I experienced the Hasidic soul and at the same time, became aware of the summons to proclaim it.

Dr. Michael Poliakoff 06:25: There's something very wonderful about the Hasidic impulse to make every aspect of life into an act of sanctification. And, as I cannot remember which one of the rabbis said, a piece of leather could make a pair of shoes for you, or it could make to fill in the phylacteries with which a Jewish person (used to be just men, now it's also observant women) each morning would worship God, bind it as a sign upon your hands and frontlets between your eyes, as it says in Deuteronomy, chapter six. And you know, people with that inspiration go through the world looking for ways to make the ordinary special, to make it sacred, and I love what is in the corpus of Nachmanides.

Dr. Michael Poliakoff 07:23: May not have come from his pen, but that's not the issue, that a married couple in love with one another break through the cosmos and stand before the Holy One, blessed be He. A sexual act can be trivial, indeed, it could be criminal, but it can also be a way that our sages recognize that you worship God and, of course, you fulfill the mitzvah, the first commandment be fruitful and multiply. And so, yes, is it the Yetzer Harah that gives us that urge to connect? Yes, but I somehow, you know, I've always been troubled by calling it the evil impulse. We do know evil, but it's not necessarily coterminous with at least that aspect of the Yetzer Harah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 08:23: Yeah, yeah, these are what we often think of as the darker energies, precisely because they're unruly, right? And of course the challenge is that's not necessarily, you might say, their nature to be simply unruly and disruptive and lead us, you might say, downward, but I know, my experience is -in sexual love- if it's really love, the way I put it, it has a trajectory toward the divine. I guess I'm not thinking myself as a form of worship, that's not natural language so much to me, but it has a directionality, and the directionality is toward the divine and other sex, purely physical sex, is sort of like junk food compared to nutritious food, you know, and so you can indulge in a lot of junk food. Or this can be directed and used and occur in the right moment and the right context, with the right meaning for the participants, and that seems to be true of this kind of erotic energy, using the term erotic in a broader way.

Dr. Michael Poliakoff 09:45: I'll turn it to you as the one-time chair of the Department of Philosophy at University of Colorado. This is Plato.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 09:57: Yes, yes, I almost cited Plato. That pull downward and the pull upward.

Dr. Michael Poliakoff 10:03: I just need to share, since we're on the subject of Hasidim, a wonderful personal story. I went to the local Chabad one night to celebrate Simchat Torah the moment when we complete the annual reading of the Torah and as I walked in it became immediately clear to me that the Rebbe was a tad on the drunk side at the celebration, which was quite wonderful and he pulls me towards him and insists that I dance with him. And he stops and he says to me, “Mordechai,” I mean, I'd not been there so many times, but he remembered my name. He says, “Mordechai, you have children.” And I said, “Yes, yes, I have children.” He says, “You know, what makes you the happiest is when your children are happy. This is what God wants from us to be happy.”

Dr. Jerry L. Martin: Yes, exactly

Dr. Michael Poliakoff: So even getting a little drunk was an act of sanctification.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 11:07: Oh yeah. Drink is part of camaraderie. It's much like the junk food and the nutritious food. If it's used properly, you know, it's a way of helping people relax and relate in an easy and authentic way and an open way often. So, it just is easy to abuse, like all of these urges that are things like ambition is part of the evil urge as I understand it, and ambition can lead people to be ruthless and to other people in and so forth, and to just to compete, maybe even to make sure let the air out of the other guy's car tires or something if you're in a race, or it can be what leads you to find, Jonas Salk, to find the Salk vaccine. You know, when you see these DNA scholars, Watson writing the memoir about it, they were in a race because in science the first one to get it, even if it's one day ahead, is the one who's famous, gets the credit and okay, well, that moved them toward great scientific discovery.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 12:15: So, because our motives don't have to be pure, they just have to be well-directed, pointed in the right direction.

Dr. Michael Poliakoff 12:23: And, of course, there's a reason why there are the 613 mitzvot, and all of the volumes of commentary that define that we do need these structures. Interesting. I'm just now trying to become more familiar with Emmanuel Levinas and extraordinary powerful thinking.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin: A great Jewish philosopher of the 20th century.

Dr. Michael Poliakoff 12:57: Yes, people of Heidegger, who broke with Heidegger, of course, lent in an element of love and humanity into the Heideggerian method. That is really quite wondrous, but Levinas really, really emphasized the aspects of Judaism that were all about the way we live with one another, our obligations to one another. The core of Jewish ethics. The definition of the God whose name we seek is a very dense philosophy, but at the core of it is that structure by which we live- what it is that we have to give to the world and share with the world.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 14:03: Yes, yes, and didn't he talk about, like the human face, how it can relate one person to another in a truly human way?

Dr. Michael Poliakoff: Yes, yes.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin: Yeah, explain that if you will.

Dr. Michael Poliakoff 14:22: Dasein the Heideggerian moment. It's not enough, it has to have, translating from the French, the other, which of course as a literary critical term, becomes a little…

Dr. Jerry L. Martin: But he used it before the later...

Dr. Michael Poliakoff: Yes, indeed.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin: Literary term and seems to have just meant something almost like the I/thou Buber, something like taking the other person fully seriously as another person.

Dr. Michael Poliakoff: Yes, yes.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin: Something like that, which is more challenging than we think because we relate mainly to each other in sort of functional roles. You know, to go to the restaurant, I don't have a big relationship with the waitress, although I like to be nice to waitresses because I think they work very hard for us but most of our interactions are rather functional and perfunctory and just trying to move on to the next thing, because we of course get a lot of help from each other, just moving through, getting gas in the car or whatever. But there's a way of relating that's deeper than that and ideally there should be some element of that even in relating to the gas station attendant, the waitress, anyone one encounters. They're a full other human being and you see that by looking at their face and their eyes.

Dr. Michael Poliakoff 15:42: Yes, and it's not a surprise that one of the great humanitarians of our time, Bernard Henri Levy, is a very serious scholar of Immanuel Levinas.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin: Oh, is he?

Dr. Michael Poliakoff: Yes, you can see that kind of writ large in the inspiration behind Levy's work.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 16:06: Yeah, interesting.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 16:42: Something I was talking too with Scott Langdon the other day, in fact I think it's going to be in a podcast, was the Carl Jung's theory, going back to that term, evil. And let me just read a little more of this before I mention what we had been talking about. The creative force of the evil urge, as I'm restating Buber, the erotic energy that I felt to be at the center of being itself, the most divine thing, you might say. And Freud has so disturbed our talk about the erotic that it's even hard to broach the subject because it's degraded in Freud's analysis, so we have to set that aside. And another place this is an actual quote from Buber, that's in the episode, “The quality of fervor with direction, all the awesome power of the evil urge taken up in the service of God.” So, it's an awesome power if you use it in the service of God.

Dr. Michael Poliakoff 17:55: That depends on having that grasp of the transcendent. In other words, we're not building a Tower of Babel because we think that we're so great. The ego of the person in all its pathetic smallness is not what this is about. It is that great task and of course I'm so glad that you have so much of the cabalistic impulse and inspiration in the God book is to be the co-worker with God as best we can understand God and not to have the arrogance to say that we necessarily do this is something beyond us but to do our best to understand what the duties and roles that are that God has appointed to us and to be led by that into that erotic fervor.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 18:58: Yes, yes, one of the things I've been talking to Scott Langdon about that I was going to mention is, I mean, part of what's involved here is we have these somewhat unseemly urges that nevertheless have a lot of creative force and can be channeled Godward. And we've given several examples already and a point Carl Jung makes, the great psychologist, he makes a distinction between the persona, which is how we like to think of ourselves and present ourselves as sort of flawless, you might say, and benign and perfect, and the shadow self which is oh, we're also aware at the back of our mind, well, we're not this perfect, brilliant, shining orb. We also have these other impulses and desires and so forth, and his warning is against just repressing those and instead integrating them, which would be another, that's what I take it as sort of what’s called for here in what Buber is saying about the evil urge, that the challenge is not to deny that you have it or try to stifle it out.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 20:21: A lot of religious people seem to me to be trying to levitate or something, as if they can jump out of the world, out of reality, and maybe even you have the extreme version and the Gnostics where they think well, God did a crummy job in the world.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 20:35: Why is it so much? So we should just sort of deny it, or even deny that God, that God just didn't live up to our standard for what God should be. But the sounder view, the healthier view, even in just psychological terms, is to say the world is mixed. It's what I sometimes call rough terrain. There's a lot to be done in this rough terrain, and we are rough numbers, we and our fellow human beings, and so we often have to be at odds with each other and fight over things and raise our fists. And the challenge is not to deny that you have those moments of anger, because anger can be either out of control anger, or it can be a righteous indignation. But so it's to integrate those urges and forces within us rather than denying them, and use them in this creative way, as Buber puts it, in God's service.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 21:43: And that, of course, takes us back to the whole nature of the great human project. We are not designed, we are not built to be perfect with perfect impulses. We are built to struggle. We are built to be part of that process. I'm going to use the title of the late Rabbi Jonathan Sack's book Part of that Process to Heal a Fractured World and to see that even in great breakthroughs there are going to be those who are left behind. And to remember our obligation not simply to celebrate the victory but also to make sure that we heal and that we help those who were not part of the breakthrough.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 22:36: I guess I ask in some form somewhere in the book, I ask God, why didn't you make the world perfect rather than having these? Why do we have diseases, for example? Why do we have accidents, that there's an avalanche and people get buried by a ton of snow? Why do we have those things? And what I was told is something like the necessity of friction.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 23:05: The world has to be real and to be real, this is my sort of summary as I understand it, to be real, it has to be material, and if it's going to have intelligent beings like us and animals, you have to have organic life. And if you're going to have an organic life, you're going to have birth, childhood, adulthood, old age and death at the end. And some of the time you're going to get sick or you're going to trip over something and fall in the lake and go gargle, gargle, you have trouble breathing. Those things will happen.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 23:47: Moreover, I've also told there's necessary work in this world for us to do. God needs partners. It's not, the world isn't just what they have, games, you know computer games, where you kind of create little virtual realities that you design that have no real point other than the entertainment of the gamer and there can be fun and fascinating and so forth, but our world is not like that. It's a real world with necessary tasks, and God needs our help in it oddly enough, Powerful God. But we're down here and God is not.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 24:32: And Abigail sometimes says God can't mail a letter. They're just things we need to do. We have to do a lot of the heavy lifting ourselves, and that's our partnership, and it's really a wonderful thing. Not that God needing our help doesn't make God pitiful or something. It's all the better that we're partners in the world and that God created a world in which, because of these rough aspects of reality, he needs partners. Moreover, that's what gives our lives meaning that we're engaged in the drama of working with God to overcome evil, disease, whatever. That's what you just called, Michael, the fractures. I guess, quoting Jonathan Sacks, the great rabbi of England recently deceased, there's necessary work to be done.

Dr. Michael Poliakoff 25:23: And this brings us back to another concept that I've always loved, that of the middle stoa, the idea that our obligation is to make the logos the guiding reason of the world, of the universe, writ large in the institutions that we build, and that is one of the most inspirational concepts that I've ever encountered. I'm actually now, talk about taking on too many things, in my 70th year, I'm still teaching.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin: Congratulations. You're still teaching!

Dr. Michael Poliakoff 26:07: I'm still teaching. No, I do it only online because I don't have the time to drive back and forth to the George Mason campus, but I teach either classical mythology or legacy of Greece and Rome, which I've renamed Antiquity’s Greatest Hits. But we're right now reading the Oresteia of Aeschylus, which I place in my own hierarchy as the greatest drama ever written, and that's not because I don't love Shakespeare, but it is such a confrontation with the enigmas of the world, the enigmas of our understanding talking here as a Greek of the gods and, most important, our ability to build institutions that will take us out of the cycles of violence that even the gods have not been able to set right. That moment in the play when Athena sets up a law court on the Areopagus, saying that, “This case is too hard for me to solve, these jurymen will solve it.” What a wonderful reminder that we can certainly go astray, and we have, and we will, but we have the tools to solve problems that are at the very core of our existence and that's what life is all about. And certainly in the Judeo-Christian tradition, which I do cherish, we're being given that challenge all the time and we want to embrace that.

Dr. Michael Poliakoff 28:08: I want to share just one other little tidbit that is very revealing. You know, there's a Jewish prayer for just about everything, and one of the ones that is so puzzling when you first encounter it is the prayer that you're supposed to say after you have relieved yourself, after you've gone to the toilet, and you bless God for the almost literal translation, the ducts and the tubes without which we couldn't function, and so, instead of you know making this something that is a shameful act, it becomes an act of sanctification of God. I've kept my body functioning. Thank you very much, God.

Dr Jerry L. Martin 29:04: Yes, and when you get older you become even more grateful for all of this, and more amazed. At least I do, more. I never knew much about biology, physiology and so forth. You knew more because you've been an athlete and so forth. But I've learned.

Dr Jerry L. Martin 29:21: Gee, all of these systems have to work together and until I got old they worked together automatically in an amazing way. But when something goes wrong you're aware oh, it's all fine tuned, you know, and so, of course by your behavior and self care and maintenance, you can help keep that functioning. The way the auto mechanic helps if you do an annual inspection or whatever, but we do that daily with our bodies, minds and souls is we keep them functioning, because they don't function just automatically. But God's available to help us with the whole thing. That's part of the great thing. Well, I think that we've said enough and that's a wonderful discussion in my view. Thank you very much, Michael. It's wonderful having someone so learned, sharing, and I think it's all relevant very much, not just a metaphysical speculation, but to life wisdom, to how one should live today.

Dr. Michael Poliakoff 30:28: Jerry, thank you. Every conversation I have with you is uplifting and inspiring, and I'm very grateful to have the privilege of being able to help in any way with this. Whatever wisdom I have, I'm just delighted to vote to such a wonderful cause. Thank you for giving me the opportunity to be part of this.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 30:53: Well, thank you, Michael. It's a wonderful friendship. We've known each other a long time and it's been a very fruitful, productive, creative and, I think, in the end, divinely oriented, though we weren't day to day thinking of it that way, but I think that too.

Scott Langdon 31:32: Thank you for listening to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. Subscribe for free today wherever you listen to your podcasts and hear a new episode every week. You can hear the complete dramatic adaptation of God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin by beginning with episode one of our podcast and listening through its conclusion with Episode 44. You can read the original true story in the book from which this podcast is adapted, God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher, available now at amazon.com, and always at godanautobiography.com. Pick up your own copy today. If you have any questions about this or any other episode, please email us at questions@godanautobiography.com, and experience the world from God's perspective as it was told to a philosopher. This is Scott Langdon. I'll see you next time.