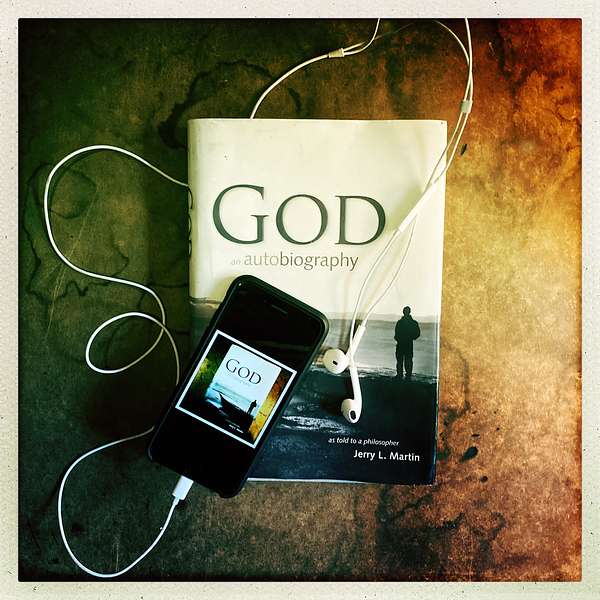

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

194. Special Episode | Revisiting God Shares His Earliest Interactions In Chinese Spirituality

Can the spiritual essence of a culture be captured through its relationship with nature?

Join Dr. Jerry L. Martin and Scott Langdon as they revisit the dramatic adaptation of "God Shares His Earliest Interactions In Chinese Spirituality."

In this captivating episode of God: An Autobiography, The Podcast, Dr. Jerry L. Martin, a former lifelong agnostic, delves into a profound dialogue with God, exploring the deep spiritual and cultural dimensions of the Chinese people.

With a holistic and reverential attitude toward nature, ancient Chinese wisdom serves as the bedrock of societal harmony and inner peace, revealing how Nature acts as a divine medium, conveying God's messages. Discover how ancient Chinese culture attunes to the natural world's rhythms, capturing its vibrations through poetry, folk songs, and intuitive spiritual sensibilities. This episode offers a unique exploration of divine communication interwoven with cultural heritage.

Listeners will journey through the teachings of Confucius, whose philosophy is rooted in societal craftsmanship and fittingness, and Lao Tzu, the sage behind the Tao Te Ching, who emphasized the mysterious and paradoxical nature of the Tao. These ancient philosophies reflect a divine sensibility in harmony with the universe's rhythms.

Whether you're a seeker of wisdom or curious about the intersection of spirituality and culture, this episode provides a profound exploration of how God has revealed truths with themes of reverence for nature and harmony with the divine.

Other Series:

The podcast began with the Dramatic Adaptation of the book and now has several series:

- The Life Wisdom Project- How to live a wiser, happier, and more meaningful life with special guests.

- From God To Jerry To You- a brand-new series calling for the attention of spiritual seekers everywhere, featuring breakthroughs, pathways, and illuminations.

- Two Philosophers Wrestle With God- sit in on a dialogue between philosophers about God and the questions we all have.

- What's On Our Mind- Connect the dots with Jerry and Scott over the most recent series episodes.

- What's On Your Mind- What are readers and listeners saying? What is God saying

Resources:

- READ "He Got Most of it Right"

- DRAMATIC ADAPTATION PLAYLIST

- LIFE WISDOM PROJECT PLAYLIST

Hashtags: #godanautobiography #godanautobiographythepodcast #experiencegod

Would you like to be featured on the show or have questions about spirituality or divine communication?

Share Your Story | Site | Facebook | Instagram | Twitter | YouTube

Scott Langdon 00:17: This is God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. A dramatic adaptation and continuing discussion of the book God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin. He was a lifelong agnostic, but one day he had an occasion to pray. To his vast surprise, God answered- in words. Being a philosopher, he had a lot of questions, and God had a lot to tell him. 194. Welcome to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast.

Scott Langdon 01:24: I'm Jerry Martin and this is Episode 194. After God explains to Jerry that the diversity of revelations isn't the problem so many have made it out to be, God takes Jerry back to the early days of the Chinese people and the Chinese mind. Jerry begins to understand that God communicates not only with individuals but also with and through cultures. In our next Life Wisdom Project episode, Jerry welcomes back a dear friend of the podcast, Jonathan Wiedenbaum, to discuss the myriad ways God comes to us as humans. So this week we bring you Episode 20. God Shares His Earliest Interactions In Chinese Spirituality. I hope you enjoy the episode. Episode 20.

DRAMATIC ADAPTATION: God Shares His Earliest Interactions In Chinese Spirituality

Jerry Martin - voiced by Scott Langdon

The Voice of God - voiced by Jerry L. Martin, who heard the voice

Jerry Martin 02:18: To find the beginning, I looked for the Chinese Moses or Socrates, but books on China don't start with individual thinkers or religious leaders. They start with the “Chinese mind” or the “Chinese spirit.” Lord, I'm not finding a founder of Chinese religions.

The Voice of God 02:47: Your approach is too individual, too Protestant. I communicate not only with individuals, but with peoples, and my instruments of communication include not just words and voices, but institutions, traditions, mores, historical currents and trends of the like. I speak to people through their cultures, as a voice is through air. I am part of the warp and woof of men's (people's) mental lives. Culture is inspired.

Jerry Martin 03:20: And to the Chinese in particular?

The Voice of God 03:23: I communicated a holistic, reverential attitude to Nature as a whole, which is the foundation for the idea of harmony with Nature as a guide to conduct and "salvation".

Jerry Martin 03:37: Nature is capitalized to indicate that what is meant is not nature in the sense of a picnic in the woods or nature as defined by contrasts such as nature versus nurture, nature versus convention, or nature versus human artifacts. Rather it is the overarching Nature that encompasses them all. For the Chinese, Heaven (T' ien) is a level, the highest level, of cosmic Nature. The ancient Book of Odes advises, "Always strive to be in harmony with Heaven's Mandate." Lord, am I on the right track?

The Voice of God 04:22: Yes, but what you haven't picked up on is the Chinese aestheticizing of Nature, which is both broad and fine-tuned. Look at that poetry. The references to flowers and the like are not the kind of awe and fear that inspired early Greek polytheism, nor a vague holistic wonder at the universe as a whole. It reflects a sense of the expressive side of Nature, which is, of course, My expressiveness through Nature. They were subtle and picked up on that.

Jerry Martin 04:51: Looking at classic odes, I found that some of them are hymns, used in religious and state ceremonies. Others that arose among the common folk are simple songs, accompanied by a zither, that tell in a direct and honest way about life, love, and loss. The action is often set in nature, sometimes in the sense of Nature as an authoritative context. Lord, what was special about Chinese culture?

The Voice of God 05:22: The Chinese are an unusual people. They resonate to Nature, feel its tones and rhythms, are attuned to it, and it "tells" them certain things. They catch its vibrations and try to match their vibrations to it. This in turn brings inner peace and harmony. And it is a right response to the cosmos. There is a natural rhythm and ordering that is healing for the soul to conform to. It is not like Dike, some sort of divine law or righteousness or duty.

Jerry Martin 06:07: The Greek idea of dike meant not transgressing the proper limits, hence justice or right order. This is not the Chinese understanding of that order.

The Voice of God 06:09: It is more like joining an instrumental group and fitting in with the harmonies, the patterns. For the Chinese, it is very intuitive, a sensibility, not like the Stoic logos.

Jerry Martin 06:23: The Stoic logos was a divine rationality that informs the universe and to which the rational soul conforms. For the Chinese, what is needed is not rationality, but a fine-tuned sensibility.

The Voice of God 06:39: One of the things I put into the universe, one of the things I am, is the natural order and the prime tone or "metronome" or tuning fork. There is a divine hum to the universe, and that is one way I communicate. So I "set aside" this whole people and communicate with them very profoundly in this way.

Jerry Martin 06:57: And the Chinese were adept at picking up the signal?

The Voice of God 07:07: They have both a natural temperament and cultural, linguistic, and symbolic resources that lean them this way, much more than in the West. People cannot take everything in at once. They have to specialize and the Chinese have specialized in this.

Jerry Martin 07:26: With little or no sense of a personal God, didn't they lose a lot?

The Voice of God 07:31: Everybody loses a lot. No one gets it all in. That is fine. They all help Me realize, express Myself. They are all part of the big story.

Jerry Martin 07:44: At this point, I was told just to sit with God for a moment. I was led into my inner self. Looking at nature from that vantage point, I saw it aesthetically. Samuel Taylor Coleridge said that fiction requires "the willing suspension of disbelief." The aesthetic attitude requires the willing suspension of desire. That allows the order and beauty of nature to reveal itself, uncoerced. That is the difference between art and decoration and, more radically, between the appreciation of nature and seeing it as something to be dismantled for other uses. It is the difference between inflicting ourselves on nature and letting the divine reality show through. The Chinese had let the divine reality show through.

Jerry Martin 08:59: The great teacher of China was Confucius. The story has it that, as a young man, he went through a period of intense meditation on what he should do with his life. He began having recurring dreams about the Duke of Chou, one of the legendary patriarchs of China, the embodiment of wisdom and virtue. Confucius believed these dreams were sending him a message. He was to revive the ancient ways and the classics from which they could be learned. This was to be his most enduring legacy. It is a great story, but as I read it, I kept hearing,

The Voice of God 09:38: No, not from dreams.

Jerry Martin 09:40: Lord, where did Confucius get his inspiration?

The Voice of God 09:50: He got it from his sense of fittingness. For him, duty was a kind of fittingness. It was fitting that a son pay appropriate honors to his father.

Jerry Martin 09:55: This is something the young Confucius, raised by his widowed mother, had managed to do in spite of great difficulties in even locating where his father had been buried.

The Voice of God 10:07: It was fitting in an almost literal sense, like putting the square peg in the square hole, or putting each puzzle piece exactly where it goes without forcing it. It is the fittingness of an artisan, a craftsman, who knows, who virtually sees where each piece should go, where the edges need to be smoothed, where the joints need to be fitted together. He saw society in that way and was a craftsman of society. If fathers behaved fittingly toward their sons, and vice versa, and husbands to their wives, and kings to their subjects, and so forth, then all the pieces would fit, without being forced. You can understand his sayings in this light. You call the Chinese approach "aesthetic," and that is not wrong. But "aesthetic" means many things, and for Confucius, it means the aesthetics of the master craftsman, writ large.

Jerry Martin 11:09: Confucius describes the superior person: "In seeing he is careful to see clearly, in hearing he is careful to hear distinctly, in his looks he is careful to be kindly; in his manner to be respectful, in his words to be loyal, in his work to be diligent." Proper behavior cannot be achieved by conforming to a general rule. One must pay careful attention to the situation and adjust behavior in the most fitting way, for, in the Confucian version of the Golden Mean, "To go too far is as bad as not to go far enough."

Jerry Martin 11:54: Words should fit deeds, with neither excessive pride nor false modesty. What to say, or whether to speak at all, depends on what words, or silences, are fitting to the person and the situation. "Not to talk [about the Way] to one who could be talked to, is to waste a man. To talk to those who cannot be talked to, is to waste one's words." Confucius presented one version of the Way. There was another, presented by his older contemporary, Lao-Tzu.

Jerry Martin 12:51: The great work in the Taoist tradition is the Tao Te Ching, the Book of the Way and the Power. At first, I thought this would be the place to begin my Chinese studies but was warned,

The Voice of God 13:08: Don't assume that every text enshrined in the history of religion is an authentic or pure communication from Me. The Taoism of Lao-Tzu reflects a great deal his own personality--shy, reticent, unassuming. I communicated a grain of truth to him. The rest is his own invention or elaboration. Find that grain of truth.

Jerry Martin 13:47: This is what I learned. Confucius had taught the rules of behavior appropriate to various social roles. Lao-Tzu was less interested in the ways of the world and more interested in the Way, the Tao, that lies beyond language and reason. The two men are said to have been contemporaries, living around the fifth or sixth century b.c.e., about the same time as Socrates. Writing a few centuries later, the great historian Ssu-ma Ch'ien, the Tacitus of ancient China, reports that the two sages met in the capital of Loyang, where Lao-Tzu, the older of the two, was curator of the royal library. Lao-Tzu told Confucius: The men about whom you talk [the wise rulers venerated in the classics] are dead, and their bones are mouldered to dust; only their words are left.

Jerry Martin 14:39: Moreover, when the superior man gets his opportunity, he mounts aloft; but when the time is against him, he is carried along by the force of circumstances. [The outcome depends, not on his will or talent or moral cultivation, but on whether he is attuned to the flow of the situation.] I have heard that a good merchant, though he have rich treasures safely stored, appears as if he were poor; and that the superior man, though his virtue be complete, is yet to outward seeming stupid. [Those in touch with the Way have no need or desire to flaunt their wealth or virtue.] Put away your proud air and many desires, your insinuating habit and wild will. They are no advantage to you--this is all I have to tell you. After the meeting, Confucius is supposed to have said: “I know how birds can fly, fishes swim, and animals run. But the runner may be snared, the swimmer hooked, and the flyer shot by the arrow. But there is the dragon: I cannot tell how he mounts on the wind through the clouds, and rises to heaven. Today I have seen Lao-Tzu, and can only compare him to the dragon.”

Jerry Martin 16:02:The historian adds his own epigraph. "Lao-Tzu cultivated the Tao and its attributes, the chief aim of his studies being how to keep himself concealed and remain unknown. He continued to reside at the capitol of Chou, but after a long time, seeing the decay of the dynasty, he left it and went away to the barrier-gate, leading out of the kingdom on the northwest. Yin His, the warden of the gate, said to him, "You are about to withdraw yourself out of sight. Let me insist on your (first) composing for me a book." On this, Lao-Tzu wrote a book in two parts, setting forth his views on the Tao and its attributes, in more than 5000 characters. He then went away, and it is not known where he died. He was a superior man, who liked to keep himself unknown.

Jerry Martin 17:05: The book he wrote is the Tao Te Ching. CChing means not just a book, but the Book, an authoritative classic or canon. The character Tao is composed of the characters for "moving on" and "head," hence, "going ahead." The original meaning was "way" with the connotations of both path and method. In this respect, it is similar to the Greek hodos, originally meaning "path," from which we derive the term method (meta-hodos, "according to the path"). As method, the Tao also suggests such ideas as principle, rationality, or reason, hence the right way or truth, and finally rational speech or word. In this respect, it resembles the Greek logos, which means both "word," as in the opening of the Gospel of John ("In the beginning was the Word"), and "reason," which we retain in such words as logic and sociological, reasoning about society.

Jerry Martin 18:20: But etymological analysis is not dispositive when one comes to interpreting the Tao Te Ching. Take the famous opening line, usually translated as, "The Way that can be spoken of is not the eternal Way." I am told that, in Chinese, the line has only three characters, the last with a negative indicator, each of which means Tao. Literally, it looks like: Tao Tao not-Tao, which suggests that the Tao that is Tao-ed is not the Tao. Another translation captures the repetition: "The Reason that can be reasoned is not the eternal Reason." The "can be" is interpretive, since there are no modals in Chinese, and no tenses. Alan Watts suggests that the element that expresses "going" and forms part of the character for Tao also has the connotation of rhythm. Hence the Tao could be understood as intelligent rhythm, the rational pulse of the universe. I remembered that God had described Himself as the divine metronome.

Jerry Martin 19:32: Whatever the best translation, the Tao is elusive and clothed in paradox. Whatever can be said must be said with a certain assertorial lightness. What can we say about it? First, the Way does not seem to be a Creator standing over or outside the world. For example (from the English translation by Alan Watts): "All things depend upon it to exist,/ and it does not abandon them./ To its accomplishments it lays no claim./ It loves/ and nourishes all things,/ but does not lord it over them." But there is a kind of creation story, which has some resemblance to what I have received about God "before" Creation. "There is something obscure which is complete before heaven and earth arose; tranquil, quiet, standing alone without change, moving around without peril. It could be the mother of everything. I don't know its name, and call it Tao." The Tao provides everything without having to do anything: "The Tao does nothing, but nothing is left undone."

Jerry Martin 21:01: What about the other key term, Te? In Confucius, Te is virtue, character, or moral force, and requires moral cultivation. For the Taoists, it is virtue in a gentler sense. Lao-Tzu's great successor, Chaungtse, writes: "When water is still, it is like a mirror, reflecting the beard and the eyebrows. It gives the accuracy of the water-level, and the philosopher makes it his model. And if water thus derives lucidity from stillness, how much more the faculties of the mind? The mind of the Sage being in repose becomes the mirror of the universe."

Scott Langdon 22:24: Thank you for listening to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. Subscribe for free today wherever you listen to your podcasts and hear a new episode every week. You can hear the complete dramatic adaptation of God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin by beginning with episode one of our podcast and listening through its conclusion with Episode 44. You can read the original true story in the book from which this podcast is adapted, God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher, available now at amazon.com, and always at godanautobiography.com. Pick up your own copy today. If you have any questions about this or any other episode, please email us at questions@godanautobiography.com, and experience the world from God's perspective as it was told to a philosopher. This is Jerry Martin. I'll see you next time.