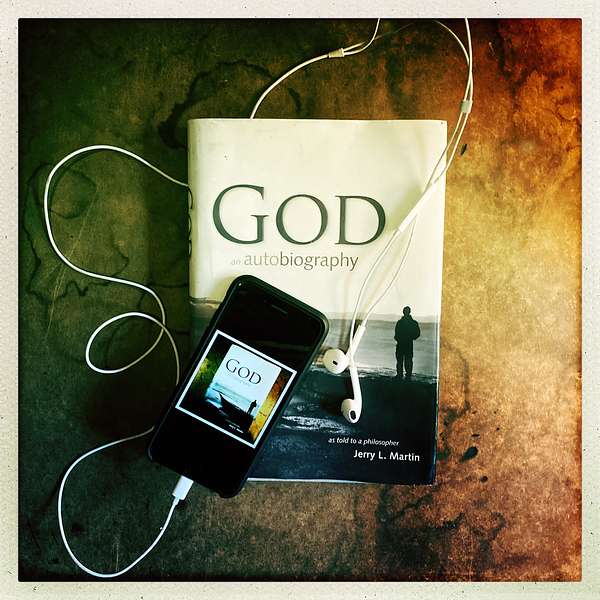

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

201. The Life Wisdom Project | The I Ching and God’s Guidance: Balancing Taoist Harmony, Confucian Action, and Ethics of Care | Special Guest: Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum

In this episode of God: An Autobiography, The Podcast, we return to the Life Wisdom Project with a profound exploration of spiritual guidance, featuring Dr. Jerry L. Martin and Professor Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum. Together, they explore the wisdom of the I Ching, an ancient Chinese text offering insight into life's 64 fundamental situations and its role in God’s interactions with early Chinese seekers.

The conversation highlights how Taoist and Confucian philosophies—balancing harmony, passive acceptance, and active engagement—provide a richer understanding of how to live in alignment with the cosmos. Dr. Martin and Weidenbaum discuss God’s revelations to the Chinese compared to the Israelites, offering valuable lessons on divine commands versus situational wisdom. The episode also touches on the ethics of care, exploring how relational ethics can guide us in complex moral dilemmas.

Listen as Jerry and Jonathan unpack the beauty and harmony of the universe, and how spiritual discernment plays a vital role in navigating both daily life and deeper spiritual journeys.

Key themes include:

- The I Ching as a tool for spiritual guidance

- Taoism’s wu-wei and Confucianism’s focus on action

- Comparing God’s commandments to situational wisdom

- Ethics of care and its role in moral discernment

- Finding joy, harmony, and beauty in everyday life

Tune in to discover how ancient wisdom and modern ethical thought can enrich your spiritual understanding!

Relevant Episodes:

- [Dramatic Adaptation] God Explains the I Ching

Other Series:

- From God To Jerry To You- A series calling for the attention of spiritual seekers everywhere, featuring breakthroughs, pathways, and illuminations.

- Two Philosophers Wrestle With God- Sit in on a dialogue between philosophers about God and the questions we all have.

- What's On Our Mind- Connect the dots with Jerry and Scott over the most recent series of episodes.

- What's On Your Mind- What are readers and listeners saying? What is God saying?

Resources:

- READ: "A Spiritual Reawakening"

- THE LIFE WISDOM PROJECT PLAYLIST

Hashtags: #lifewisdomproject #godanautobiography #experiencegod

Share your story or experience with God! We'd love to hear from you! 🎙️

Share Your Story | Site | Facebook | Instagram | Twitter | YouTube

Scott Langdon 00:17: This is God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. A dramatic adaptation and continuing discussion of the book God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin. He was a lifelong agnostic, but one day he had an occasion to pray. To his vast surprise, God answered — in words. Being a philosopher, he had a lot of questions, and God had a lot to tell him.

Episode 201 – Welcome to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. I'm Scott Langdon. This week, we return to our regular programming schedule and bring you our 21st edition of the Life Wisdom Project. Jerry is joined once again by Professor of Religious Studies, Jonathan Weidenbaum, to discuss the implications for all of our lives from Episode 21. God Explains the I Ching. It's in this chapter that God tells Jerry some more specific details about His interactions with the early Chinese people and how their way of seeking God and looking for guidance taught God new things about God’s self. It's a wonderful conversation. You won’t want to miss it.

Here now is Episode 201 and our 21st Life Wisdom Project. I hope you enjoy the episode.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 01:55: Jonathan Weidenbaum, I’m very glad to be talking to you again and especially about this episode where I pray about the I Ching, the Book of Changes, as the translated title would be. The changes refer to 64 fundamental human situations, the way it has it broken down, and there’s a kind of cryptic advice, imagistic in part, with a different conceptual background, not necessarily familiar to a modern Western thinker. Each one of those is given some kind of guidance in the I Ching, and in the traditional form, people choose them by lots, by casting coins or something to see which section to consult.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 02:59: I’m told in prayer that this is not magic. Nevertheless, it kind of works, you know, and that’s kind of puzzling. How is it that it works? But to pay attention, because it’s one way of connecting with the divine or whatever language you want to use — the fundamental flow and normative structure, even harmony, of the universe. And well, when you look through this or listen to the episode, Jonathan, what struck you as the point of the life wisdom? What are the takeaway lessons, things we can learn for living from this discussion I had with God about the I Ching?

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 03:50: Well, this was such a rich chapter, and it seems to me that one prevailing theme I see in the God book in general is so many facets of the divine are reflected in it. You know, the idea of a transpersonal cosmic ground, the idea of a personal, active deity who loves, who cares. What strikes me profoundly about this chapter is that we see the human analog for that. You know, if you think about it...

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 04:27: You know, in Taoism, there’s a certain stress on being like an uncarved block, a certain sense of moving in harmony with nature, wu-wei — not forcing ourselves on things, accomplishing more by not forcing ourselves on things, but sort of being in harmony with the cosmos.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 04:46: So, a kind of — this is a strong tag — but a mystical quietism. You know, perhaps quietism is not the best term, but maybe a sense of basking in the nature of things and, as I’ve mentioned a few times, not shoving ourselves on things or pushing too hard. On the other hand, Confucianism, the idea of rectification of names and knowing our place in the social harmony, cultivating proper relations to others and propriety, and ritual. There’s a strong sense of the active, of the doing. These are just classic demarcations people have when they talk about Chinese thought and religion. What was emphasized in this chapter is the manner in which these are harmonized — in which the I Ching serves as ground for both religious traditions, and in which they have not yet sort of gone in such different directions, and so it has a much more richly integrative understanding of how humans should live in the cosmos.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 05:52: That diversity that you stress is very much here. There are multiple types of situations, even to some extent different types of people, who find themselves in different kinds of situations. And as you mentioned, there is a kind of emphasis on something like the Taoist view. But it’s funny, the complications here. I’m told at one point you have to fight in life against the flow. You go with the flow, but that often involves — and here’s where the quote from God ends — you have to fight against obstacles to the flow. You know, there’s a natural drift of things that’s kind of normative, that’s the right order, that’s harmonious, and yet there are obstacles to it.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 06:56: And so, in different situations, sometimes you sit back and let the situation be, let it develop, and don’t jump prematurely. Other times you do. You’re given marching orders, as I was, and I’m told that my role in producing the God book was essentially passive. I was just told what to do and I did it. I was just the instrument and nothing more. In other work in my life, I’d been the agent, and God sometimes needs that. People to, okay, take charge of a situation or solve a problem or come to the rescue, whatever it might be.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 07:42: Two parts of the chapter stand out in regard to this theme. After the halfway point, toward the end, you say the Taoists are one-sided and neglectful of the demands of action. The Confucians are one-sided, in the opposite direction. They address action but fail to fit into a cosmic context. For them, it remains at a societal level. But doesn’t the I Ching combine the two? To which God emphatically says, yes. You know, so there you have a certain richness we’ve been speaking about, that kind of reconciles these two different aspects. But also, early on, when the chapter was just introducing the I Ching and just introducing the material that went into the I Ching — the sketches or the writings on what they thought were dragon bones, but of course, was, I guess, bones.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 08:42: And God says, you know, the situation wants a certain action or attitude. The seer has to quietly listen to the situation, you know, and be more attuned to the context. That’s the idea. And I notice you then say how this contrasts to God’s issuing of commandments to the Israelites. To which God says, yes, you know, this was my communication to the Chinese much earlier. They were seeking a kind of guidance from the divine. They were trying to communicate with me, and this is how I disclosed myself to them, whereas God’s revelation to the Israelites came later, and there’s much more of an emphasis on direct commandments. Of course, quite literally, there are commandments to the Israelites, but it’s sort of urging for action, right. So it has a different kind of moral direction, and I found that very, very striking.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 09:46: There’s somewhere in the book — I can’t remember the context now — but where I was asking about this difference between, let’s say, the people of Israel and God issuing commands and something like Confucian situational wisdom. I was told, well, for certain kinds of things like right and wrong — don’t lie, don’t kill, don’t commit adultery — the commands are really good; they have some advantage. On the other hand, that’s not superior overall to what Confucian situational wisdom and attunement achieve. They each, you might say, get different work in life done. And I suppose the I Ching would say about this kind of issue, well, you have to find what the situation calls for. But with the people of Israel, you don’t ask what the situation calls for.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 10:47: God told you in advance what you’ve got to do, and it’s mainly a list of prohibitions. But not only that — some of them are positive, like putting God above all, for example, having one God before you. Well, it’s a completely different sensibility, and yet it has its own validity. And as you put it, Jonathan, God has many sides, and we have many sides, and the world has many sides. There’s not one simple recipe that’s going to handle all of reality and all of human morality, all of our situations.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 11:28: I just had an interesting conversation with one of the students in my ethics class because we were talking about Kantian ethics and utilitarian ethics, and I don’t know if I’ve ever brought this up in a prior discussion on your podcast. But with Kantian ethics, we have the categorical imperative, which you must do regardless of context or consequence. Utilitarianism, the hedonist calculus: greatest amount of happiness for the greatest number of people. But the student noticed that I, as the professor, have an appreciation for raising contexts, thought experiments, scenarios where those formulas don’t quite fit hand to glove. They shipwreck against the complexity of the context — something I discovered, by the way, even in my own major ethical dilemma when my beloved was in her final days on life support. Her parents wanted the machines to remain on, and I wanted to go with palliative care. But I couldn’t so quickly disregard the parents’ wishes, even though palliative care was pushing me to do it to the point where the head of palliative care was citing to me the categorical imperative.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 13:02: And since then, an ethical theory — if we can call it a theory, I guess we can call it a theory — that really began to show its relevance to me, which I will very soon deliver to my class and this student will be very pleased, is the ethics of care. It arises in a feminist context. It’s often compared to Aristotelian virtue ethics, and it should not shock us that anything that’s comparable to Aristotelian virtue ethics would have a lot that’s consonant with Confucianism. Ethics of care, of course, is nurturing sort of caring relationships directly to other human beings. But what’s particularly striking about the ethics of care, particularly as it’s formulated — or I could say formulated as expressed — in the works of Nel Noddings, among others, is that it puts context above formula. You know, it gives the nuances of a concrete situation and the needs of a particular relationship as more fundamental than, you know, outlining or obeying some precept or some law.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 13:54: And it’s that attentiveness to context that really a lot of people find refreshing when they first learn about it. It shows itself to be much more meaningful in various moral dilemmas like the one I faced concretely. It seems a little bit less susceptible to the kinds of thought experiments in which the more formula-based ethical theories would kind of break apart. And it seems to speak to this Confucian and Taoist emphasis — you know, whether it’s the Confucian idea of knowing our place in the social fabric and enacting the correct relationships between generations, between spouses, between friends, or the Taoist idea of just sort of moving in harmony with nature.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 14:39: Yeah, one similarity that’s striking between the ethics of care and the Confucian tradition is that Confucian ethics has a large role for the question: What is my relationship to this person? Yes, you’re going to owe a different degree of support, even candor, and everything else you can think of.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 15:11: Right, you’re going to tell one person secrets, withhold secrets from others. For example, you’re going to come to the rescue of one person. You have no obligation to come to the rescue of the other person. And your obligations to your students are not the same as your obligation to whoever’s in the next office over, and so on. And the ethics of care, if anything, seems even more intimately personal. At least, maybe this is because of the feminist background. You kind of want to know: Well, what’s the other person feeling? The person I’m reacting to — what are they going through? And what you’re thinking about in the situation you mentioned with your poor wife and her parents — you can’t just pull the plug when it might make sense to pull the plug because their intimate feelings are based in part on their relationship, in part on just the human capacity to take in things, and you can’t take them in with the snap of a finger.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 16:19: We go through emotional processes. That comes out nicely in these. It would seem that that command tradition — both of the Old Testament form and of the Kantian categorical imperative form — seems very obtuse to this aspect of life. Probably not in detail if you go through Old Testament stories, for example, and I don’t know about the details of Kant elsewhere, but certainly in the Eastern tradition, in Confucianism, there is very much the sense of — they’re somewhat stylized socially — the seven special relationships or something like that: husband, wife, parent, child, and so on. You know, your teacher, student — these are kind of privileged relationships, you might say, that carry their own rather heavy sense of obligation.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 17:54: There is also in this chapter another facet that’s missing, and maybe it isn’t fully missing, but that I don’t see in that whole commandment tradition, and that’s an emphasis on beauty. I like this quote here. This was really wonderful to come across. God says, “There are times for just being, because you already are what you should be, and so is the universe, and you should enjoy, appreciate, and understand that fact. The universe is a joy, not just an arena for action; it is a celebration.”

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 18:34: Yes, yes, that’s very striking, isn’t it?

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 18:36: Yes, it is.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 18:37: That’s not the whole of life, but that’s an important aspect of life. And if it’s time for just being and connecting, appreciating, then that’s what you’re supposed to do. Otherwise, you’re missing out on something of fundamental value, and it is aesthetic. Early on — I’m forgetting now the context — it’s the very beginning of the episode. Oh yeah, reading the oracle bones. What does it require?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 19:10: The willing suspension of desire, which elsewhere is the same attitude one takes to art. You know, the difference between, well, art and decoration or advertising images is that with art, you’re just letting them be, and you’re suspending desires. You’re not relating to the objects around you in terms of desire, I guess. Early on, this came to me in prayer, just in a cafe or something, just looking around me. And you can look around at the objects: counters, plates, utensils, people serving, and so forth. Those are all seen in terms of desire — their role, their utility — what we get out of them. However, I found I could also look at the same scene, and I suppose artists, painters, do practice this sort of thing, where I don’t classify what I’m looking at that way. I simply take it in as a scene, as colors and shapes, and there’s some deeper resonance that expresses itself — of sort of being coming through, maybe the divine coming through, or whatever. But it’s a dimension of reality that just shows itself, and you just take it in.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 20:35: Yes, it shows itself and you just take it in. This is also another facet of Confucian thought that overlaps with Aristotelian thought. Another commonality: this idea that, you know, part of the ethical life is turning into a certain type of person. You’re turning into someone that has to appreciate painting, archery, music — you know, to become the full human being. And in the context of this chapter, when it comes to a Taoist and Confucianist ethic, to really find one’s place in the beauty of nature, you know, and to appreciate what we have before us. I find that particularly a very important lesson as well.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 21:21: Yeah, and it involves — it’s where notions like harmony come in, and how that radiates through our social relations. Even the structure of society should be a kind of beautiful thing. It should be harmonious, like a symphony or something. It should be like a symphony orchestra. We’re all playing different instruments, but we should play them not raucously — you know, playing just our part as loud as we can, the tuba, boom, boom — but weave it together. And of course, sometimes it’s not like a symphony orchestra in the sense that you’ve got a score and a conductor. It’s a little more like jazz, improv. Sometimes, I think in this episode, the dancing metaphor is used. Sometimes you’re just going with the music that’s being generated, and you make your own contribution to that music. And that’s the kind of natural harmony that’s spontaneous — not an ordered, mechanized, top-down, or rationalistic harmony, but a natural, flowing, aesthetic, beautiful harmony that people have the capacity to relate to and get in connection with.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 22:42: One thing that’s striking about this chapter, and in the God book overall, but specifically in this chapter, is the manner in which God is the proper metaphysical backdrop and support for exactly what you’re talking about. For instance, I love the interactive scene when God says to you, “Take a step back.” And then you begin to ask a question about the I Ching, and God says, “No, no, no, step back further.” Then you begin to talk a little bit about Chinese civilization, and God says, “No, step back even further.” And finally, you know, you outline Chinese civilization, and then God says, “Yes, the whole, to which the parts are resonating, to which they must yield, since stratagems do not work with you.” Who embodies the order they must replicate in their lives and social relations, who is seen in the beauty and order of nature. So there’s a sense in which a little bit of reverie, just the right amount of action, just sort of an appreciation for art, just in cultivating the proper relations between yourself and another generation — all of this has its grounding and is a reflection of the divine life, and I think that’s a particularly powerful aspect as well.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 24:12: Yes, and through that, God discovered His own beauty, harmony, and musicality, you might say, by people reacting. And we help God actualize those things because a beautiful object needs a viewer, for one thing, to see it as beautiful. Abigail often says, “It takes two to make a miracle.” One, God, to do it, and the other is for us to recognize it. But that’s true of every trait that would be fully actualized. A visible object needs to be seen to be fully actualized; otherwise, its visibility means more or less nothing, you know, in practice. But it has to be realized, actualized, brought into being by someone looking at it — or, in this case, looking at it with that willing suspension of desire, looking at it with that aesthetic eye, that kind of relaxation that appreciating things aesthetically involves.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 25:20: Yeah, and looking at my own religious inheritance, even though I’m not particularly practicing, but I take pride in it. You know, this idea in the Jewish tradition: man as a co-creator, or human beings as co-creators, with the divine. You know, we’re not just reflections of God’s majesty. Rather, we’re there to help improve the cosmos — partners, if you will.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 25:46: And even though that has a much stronger ethical and ritual connotation, whereas your chapter also is more of a reflection on the beauty of things and the aesthetic, nonetheless, it’s that participatory quality. Yeah, some of the devotional aspects of the Old Testament would be a bit closer to that Eastern sense of, I think, of the Song of Songs, which is sort of love for the missing lover, which is really affective. I don’t know if you can call it aesthetic, but it kind of feels that way. Yes, the missing lover, who’s somewhat elusive — missing or elusive — is beautiful, surely.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 26:35: A little bit of that sort of dance aspect that you outline in the chapter as well. You know, the relationship between being receptive and being active. It’s really part of a momentum; it’s part of a rhythm. They should not be so in contrast with each other.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 26:52: Yeah.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 26:53: And I also appreciate how, you know, there’s a little bit of a — I don’t know what the right word is — maybe a little stab against the tendency of the intellectual tradition to be one-sided, that somehow the common person seems to embody this balance or understand it a little bit more easily. So, if I can read — I mean, I’ve read so many quotes — but if I can read one more here, God says: “Common people know the necessity for action. They bear its brunt and, of course, they want to know what will happen, hence casting sticks to predict. But they also want guidance, good advice. They don’t have the illusion of self-sufficiency that Taoists and Confucianists have.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 27:42: Yes, that’s right. Intellectuals and other kinds of leaders, perhaps, tend to think, “Oh, there’s one big answer, and they’ve got it.” Or at least they think they’re hot on its track, and that ordinary people just need to listen to their pronouncements. Meanwhile, ordinary people are taking in all of life. You know how professors are: often really very detached from the realities of life. They can pontificate about crime in the streets or something, but they live in places that are relatively safe. It’s a kind of speculative thing. They can give you the data on crime statistics or some analytical apparatus or theoretical apparatus.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 28:26: But meanwhile, I know when I visit New York, Abigail finds me shockingly naive. She is street smart. That’s how a woman makes it through Manhattan. It’s annoying, you know — not making eye contact with the wrong people, these kinds of micro-behaviors that come naturally to her, having grown up learning these skills. Intellectuals are just the people least likely to have learned those skills, and so that’s interesting. I had not remembered that part from this celebration of just people who cope with all of life. And I want to note that, you know, as a philosophically trained person, I really want my beliefs to be coherent with one another. And I’ve noticed that people who aren’t as specialized as professional intellectuals don’t have that necessity. They’re perfectly happy to have one set of beliefs that seem to them right and then another set that to my mind might seem completely incompatible, but in a different domain, that also seem to them right. And they don’t feel they have to hammer this out, you know.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 29:50: Well, it’s funny because I teach philosophy, world religions, and ethics at a for-profit, business-themed college. None of the students in my classes are philosophy majors. They’re not grad students. They often come from many walks of life and many backgrounds, but they usually have an extremely strong practical sense. A lot of them either are mothers, already have careers, or are going to go into law enforcement or business. They are very worldly, very practical, and less susceptible to ideologies that might be attractive elsewhere or to simplistic pictures of the way the world is supposed to work. There’s something a little bit earthier, a little bit healthier, a little bit more robust, a little bit more well-rounded about them. They have a better sense of the ambiguity of life, the importance of context, and the idea that sometimes our abstractions do not fit the real world. And that brings a lot of richness to our class discussions.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 30:56: Yeah, yeah. And in a way, the I Ching is perfect because I often end up in these podcasts talking a lot about spiritual discernment because it seems to me the key epistemic challenge. But when you start talking about ethical situations, caring, there are other kinds of discernment also crucial here: just moral discernment, situational discernment, even being sensitive to the other person’s feelings, empathy, being sensitive to what the relationships are, what the history is, and just the practicalities. “Hey, that isn’t going to work. We’ve got to set aside some savings,” you know — these kinds of practicalities of life. All of those kinds of discernments then have to be balanced with one another: a balancing of different factors, different kinds of value, different goods, different goals, different threats.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 32:01: You know, one theme I noticed, and you’re 100% correct. You often bring up this question — or others bring it up to you — when we’re talking about the God book or Theology Without Walls. It is the topic of discernment. How do we know a real revelation of the divine versus a specious one? How do we know what should really count as the spiritual versus the problematic? And that is a persistent theme in a lot of the work that you do and a lot of the discussions that we often have.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 32:34: In all of the writings I’ve read of yours, and I was trying to put my finger on what it is about this chapter that almost feels like it’s an answer to so many of the tensions and issues — healthy tensions, I should say — that run through your work. And part of it is that it is about kind of religious epistemology. It is about spiritual knowledge — you know, how we can discern that this comes from the divine. I mean, the way you began it, you know, the Chinese were seeking guidance.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 33:05: So, you know, on the one hand, we can understand this as a folk practice: writing on the bones and heating them up and reading the cracks, or whatever they did. But there is this stress on attentiveness — the way the text is used, the hexagrams of the I Ching are used, the way the chapters are used — and you display that throughout this very rich chapter. The way in which we let the images, we let these otherwise cryptic symbols guide us toward refining our sense of what needs to be done in a given context. So, there’s a lot here that speaks to one of the most central issues, not only of the God book but of your work in general.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 34:00: Yeah, that’s right. I’m by nature an epistemologist, so I notice some of my friends are metaphysically inclined, and they immediately start pulling generalizations out of the air — it seems to me they’re very confident in them. But I always have to go back, “Wait, why those concepts? You’re answering certain questions. Why those questions?” You know, we’ve got to go back some steps here. And it has seemed to me, dealing with spiritual matters, the key epistemological issue is spiritual discernment.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 34:30: It’s not the kind of thing the philosophical epistemological tradition has talked mainly about, which has to do with radical skepticism and so forth. No, it’s matters of discernment. And when you start thinking that way, then you evolve in the way our discussion today has, Jonathan — you start thinking about ethics as well. It’s really more of a matter of discernment, isn’t it? Which then is attuned to the situation, the person, etc. And the aesthetic dimension of life, which is also — you can’t just separate the moral from the aesthetic or the social from the aesthetic because harmony is an element of them, too. And that requires discernment or something I don’t stress very much but would be a good word, a good concept here: sensibility. You need to develop a sensibility that is sensitive to these kinds of considerations, to the spiritual dimensions, to the ethical dimensions, to the personal dimensions — including the emotional and historical, situational, practical. And you have to develop that rather complex and yet not difficult — not difficult in the sense that these are all part of being human, after all. And so, it’s not as though you’ve got to learn rocket science or something. No, quite the opposite. You’ve mainly got to live your life’s experience in the most attentive, perceptive, thoughtful way you can, attuned to these kinds of considerations.

Scott Langdon 36:17: Thank you for listening to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. Subscribe for free today wherever you listen to your podcasts and hear a new episode every week. You can hear the complete dramatic adaptation of God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin by beginning with Episode 1 of our podcast and listening through its conclusion with Episode 44. You can read the original true story in the book from which this podcast is adapted, God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher, available now at amazon.com and always at godanautobiography.com. Pick up your own copy today. If you have any questions about this or any other episode, please email us at questions@godanautobiography.com, and experience the world from God’s perspective, as it was told to a philosopher. This is Scott Langdon, and I’ll see you next time.