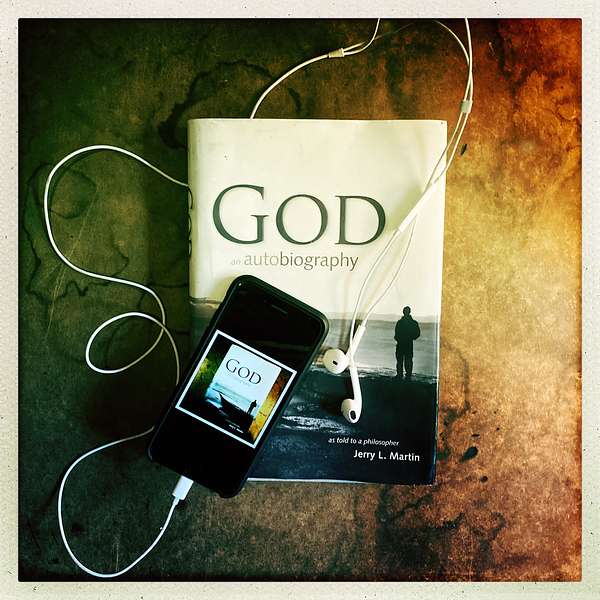

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

213. The Life Wisdom Project | Life’s Meaning: Love, Connection, and the Vertical-Horizontal Path | Special Guest: Dr. Richard Oxenberg

God: An Autobiography, The Podcast, welcomes philosopher and returning guest Dr. Richard Oxenberg in this thought-provoking Life Wisdom Project. The two explore what it means to “come up for air” when asking life’s deeper questions: how everyday tasks like grocery shopping or filling the gas tank relate to profound concepts of purpose and spiritual wisdom.

Drawing on Aristotle’s eudaimonia, Jerry and Richard discuss the distinction between intrinsic and instrumental value, and how recognizing love- whether romantic, familial, or communal- can connect our horizontal and vertical dimensions of existence.

They also examine the paradox of God as both One and Many, highlighting the yearning for oneness at the heart of all religious traditions. From insights on humility and community to practical ways of weaving prayerful intentionality into our daily routines, this enriching conversation offers guidance for anyone seeking deeper meaning and life wisdom in a diverse and interconnected world.

Other Series:

The podcast began with the Dramatic Adaptation of the book and now has several series:

- From God To Jerry To You- a brand-new series calling for the attention of spiritual seekers everywhere, featuring breakthroughs, pathways, and illuminations.

- Two Philosophers Wrestle With God- sit in on a dialogue between philosophers about God and the questions we all have.

- What's On Our Mind- Connect the dots with Jerry and Scott over the most recent series episodes.

- What's On Your Mind- What are readers and listeners saying? What is God saying

Resources:

Hashtags: #lifewisdomproject #godanautobiography #experiencegod #twophilosopherswrestlewithgod #theologywithoutwalls

Stay Connected

- God and Autobiography as Told to a Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin, and Two Philosophers Wrestle with God- A Dialogue are available on amazon and at godanautobiography.com.

- Share your thoughts or questions at questions@godandautobiography.com—we’d love to hear your story of God!

Share Your Story | Site | Facebook | Instagram | Twitter | YouTube

Scott Langdon 00:17: This is God: An Autobiography, The Podcast, a dramatic adaptation and continuing discussion of the book God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin. He was a lifelong agnostic, but one day he had an occasion to pray. To his vast surprise, God answered in words. Being a philosopher, he had a lot of questions and God had a lot to tell him. Episode 213 Welcome to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. I’m your host, Scott Langdon.

Scott Langdon 01:10: Today, on our latest edition of The Life Wisdom Project series, Jerry welcomes Dr. Richard Oxenberg back to the program to discuss Episode 23. It’s the point in Jerry’s journey with God when Jerry takes some time to come up for air, as he puts it, and asks God, “What’s the point of it all?” If you’re a regular listener to the podcast, you’ll easily remember Richard as not only a dear friend of our work here, but also as Jerry’s dialogue partner in our series Two Philosophers Wrestle With God. You can find the audio version of that series here on this channel, or you can get your hands on a brand-new copy of the book version published as Two Philosophers Wrestle with God: A Dialogue, available at Amazon.com. Here now are Jerry and Richard. I hope you enjoy the episode.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 02:02: Today, Richard Oxenberg and I are talking about Episode 23, in which I ask—it’s one of the episodes I think of as where I come up for air because I’ve been praying about particular sacred texts in different traditions or pursuing some question on my own mind—suffering, evil, ego, whatever—and I’m engaged in the pieces. Then occasionally I feel, “Wait, I’m like swimming across the Atlantic. I want to come up and look: Where is the land? Where am I?” So that coming up for air takes the form of asking God, “What is the point of it all?” And when we talk about life wisdom, you need to have some sense of what it is you’re about. You might have all the parts of one’s life—shopping at the grocery store, filling your tank with gas—what is it for?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 03:09: And you want some bigger question than, “Oh well, my car will run out of gas otherwise. We’ll run out of food otherwise.” But there are bigger questions about life and how all these projects relate together. They don’t necessarily have to relate together, but some sense of, “Isn’t life more than just putting gas in your car and charging for groceries? What more is it?” I find that this discussion with God, as often happens, God is challenging not only my particular beliefs that I brought to the discussion, but my way of thinking about the question. And that’s what happens here. Did that strike you, Richard?

Dr. Richard Oxenberg 03:57: It did. There’s always, with the book as a whole and the basic revelation, a sense of giving us a both-and rather than an either-or.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 04:12: That’s part of that “thinking differently.” God has to hammer that into me over and over—me and other people, I guess—who think in terms of “either-or”: it’s this or it’s that.

Dr. Richard Oxenberg 04:24: But not quite. There’s a teleology, and yet it’s not a means-end teleology. In other words, it’s not a teleology that comes to an end where you say, “Now we’ve finished it.” It’s a teleology that has this sort of, in a sense, a working out of the vertical through the horizontal, if I can put it that way—but the vertical always remains.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 04:56: I think that’s a good way to put it. The vertical is those aspects of transcendence and ultimacy in our lives, the final of ultimate value or importance. But we’re living life one moment to the next, putting one thing after the other, so the two have to be connected.

Dr. Richard Oxenberg 05:16: They have to be connected. But the horizontal never resolves itself. We might tend to think, “Well, you’re trying to use the horizontal to get to the vertical. You’re trying to arrive at some place and then you’re done with the horizontal.” But that’s not the way it’s presented here. It’s that every moment in that horizontal or temporal progression has the potential for reflecting the ultimate values that are part of the vertical, or somehow failing to reflect those. Every moment presents its own challenge. In some sense, that is both the meaning of life—to find the way in which this particular moment I’m living in can be reflective of what is ultimately good and true—and also the nature of life, not just in the sense of “this is what we ought to do,” but “this is what the nature of reality, the nature of the cosmos, the nature of God demands of us.” In other words this is the task that reality has set before us. Because it never ends. The horizontal never ends; it goes on and on forever. There’s no finally arriving at the vertical and saying, “Well, now we’re done.”

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 06:57: When you think of that, some people—this was my first reaction—say, “Well, that’s a disappointing answer. I want a happy ending.” I want something like a story where there’s a happy ending, and then you can see the pieces of the story as helping to bring about that happy ending. And okay, everything’s nice.

Dr. Richard Oxenberg 07:17: But there’s a real paradox to the idea of a happy ending. It’s a paradox I sometimes bring up with my students when I’m teaching Aristotle. Aristotle’s Ethics is about an examination of what he calls eudaimonia, which is often translated “happiness,” and happiness is the ultimate telos of life. The ultimate ending; everyone wants a happy ending. Sometimes I will tell my students: what do we really mean by saying that happiness is the goal of life? Do we mean once you become happy, you no longer want to live? Now I’m happy, now I can shoot myself because I have arrived at the goal of life—happiness is something to be lived. It’s not a goal that you arrive at and now you’re done. It’s a goal that you pursue in the course of living, and what you want to do is live as happily as possible, not “get to happiness” and then be finished. I think that’s an idea very much being expressed in the book here.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 08:46: Yes, I think Aristotle also makes a distinction that’s relevant here between production—activities done for instrumental purposes—and action, an activity done for its own sake. Production is done for something else, like planting seed so you can harvest next season and have food and sustain yourself. That’s instrumental, and that’s a huge part of life. We’re doing things for instrumental purposes. But there’s also action, which is the difference between our relation to nature when we are planting food and harvesting it and our relation to nature when we take a walk in the woods. We are not taking a walk in the woods to achieve something other than a walk in the woods, or contemplating a beautiful sunset- we’re not doing it for some other purpose. For Aristotle, when we contemplate not only objects of beauty but objects of intellectual interest—why do we ponder the meaning of the American Civil War? We ponder the meanings of things and we don't do it in order to do something else. That’s an activity with its own internal, self-sufficient purpose. That would be useful in thinking about living each horizontal moment-to-moment as a reflection of the ultimate.

Dr. Richard Oxenberg 10:30: The language that I've used is there's the instrumental and then there's the intrinsic. There's what is instrumentally valuable in that it leads us to something, but ultimately, the instrumental has to be for the purpose of the intrinsic. The instrumental value has to be for the purpose of achieving or bringing us closer to what is of intrinsic value.What we need to understand, I suppose, if we want to try and do this in a profitable way, is just what are those things that are of intrinsic value? I mean, that becomes one of the primary questions and is one of the questions that Aristotle asks, and I think it's a question that is implicit in God: An Autobiography, that one of the things that is of intrinsic value is to recognize one's connection with the whole. One if the paradoxes of life is that we are individuals who are dependent upon a reality way beyond us, and it is in sense, through connecting with that greater reality that our own individuality is able to achieve its true intrinsic value or come to realize that or enjoy it.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 12:20: Yeah, in this episode this is explained in part by the example of love that when you love someone you don't say what is that love for, and I think to understand, make the most of these things, the example often starts with romantic love, because that's something graspable and we all understand that kind of phenomenon, but also other forms of love, family love, love of friends, even love of community or affection for community, those bonds that you have with neighbors and so forth, that they are not there for some other reason, and that's the sort of Aristotelian test of intrinsic value. Is it something that, even without any further upshot, is a valuable moment? If it's a valuable moment, then it's achieving this relation of the horizontal to the vertical, to the transcendent or ultimate.

Dr. Richard Oxenberg 13:28: I'm trying to remember now, at the very end of that episode God speaks about, I may have written it down as a quote here that in order to understand the nature of God, the nature of life, I think God finally says one has to relax some of the logical constraints that make it difficult to accept that God can be both one and many—a person and much more than a person, immanent in nature and yet not reducible to nature. So much of this has to do with the paradox of the One and the Many. That the one, in a sense, in order for the one to realize and when I say the one now I'm talking about that which is ultimate in being, this ultimate oneness, as the book points out, as long as it remains to itself, or in its own ultimate oneness, it doesn't realize its own potentiality, it has to give rise to this incredibly diverse universe, with all its different facets and aspects and divergences and differences, in order for the one to fulfill itself. But then what we have is we have the problem of each of the separate pieces, each of the separate individuals. None of them is ontologically complete in itself. And so, in a sense, that's where longing arises, all of a sudden, you have each of these pieces, have a longing for reconnection with the whole that is beyond them.

Dr. Richard Oxenberg 15:26: I think that longing is what we experience as the longing for love: the longing to be reconnected, the longing to be somehow taken beyond the loneliness of being a separate entities. And so there's this sort of endless erotic, I think the word erotic is used in the passage— this erotic yearning is not just sexual, but in the sense of longing for union with that which is ontologically beyond us but also that in which we are contained. When we somehow satisfy that, even in fragmentary ways—like with a romantic relationship—there’s a great sense of liberation and euphoria and beauty that we experience.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 17:19: People experience that in simple moments, like joining a singing group and it all comes together, and there is something like a euphoria when it's all working. You practiced and practiced and now it’s come together and you're doing some piece of music you love. I sometimes think of your engagement in amateur theater, Richard. I know you were playing the rabbi in Fiddler on the Roof. You’re creating bonds of affection.

Dr. Richard Oxenberg 18:00: Absolutely. The thing I most wanted to be when I was younger was an actor—I ended up going into philosophy, but the thing I most wanted to do was acting. I’ve done a lot of amateur acting. I played the rabbi in Fiddler on the Roof and most recently Scrooge at a community theater. I’ve asked myself, “What is so compelling about theater?” It’s the connection you’re making with an audience. If you have a character with some depth and you’re able to enter into the depth of that character and then somehow bring it out to the audience, so that you share those moments of depth with the audience, there's a way in which, once again, you transcend your isolation, and you become one with the audience for that moment, and it's a beautiful thing. You need the audience there. You can pick up a script and I've done it sometimes and be in my own room and try and play the part just for the fun of it, but you need somebody else. You need to have it be communicated to somebody else in order for whatever it is you're trying to achieve to be consummated. That itself is also an act of love, I think.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 19:52: One of the life wisdoms here is to think of your daily life in these terms. Some religious traditions have you pray before opening your shop every morning because you’re doing that not just to make a living—which obviously is what a lot of why you're doing it's a necessary thing to do, to make a living and feed yourself and your family— the prayer is for let it be more than that. In my experience of places I frequent—shops, cafés, and so forth around town—there’s more to that interaction than just buying and selling. There’s an appreciation of the other person. Sometimes it’s a bad day and you commiserate. There are other dimensions even to these simple relationships. Your presence to what they’re going through is itself an important expression of love, a way of bringing “ultimacy” into daily life, into one’s moment to monet life. Every interaction you have with someone even your private moments, you're doing something, you're sending somebody an email or, if you're an academic, you're trying to think through some thoughts and write a paper or something, write a piece of research, even that can be done in a loving mode and with a mode that appreciates, venerates its intrinsic value.

Dr. Richard Oxenberg 21:51: When you talk about the prayer in that way it very much reminds me of Halakha in Judaism, which has a prayer for just about everything for everything to do. I'm not an Orthodox Jew, but I've known some who are. Their life is constantly a life of prayer. Every act, every mundane act–we're sitting down to eat, we're putting on our shoes – the idea of the prayer is, at least as I've come to understand it, is to make you mindful of the eternity within which every individual moment has its being, so that you're not just stuck in that one individual moment but you see that moment as having, as reflecting, in a sense, the eternal reality, and somehow to have the individual be mindful of and reflective of the oneness of eternity while pursuing his or her individual acts. That takes you outside of your isolation, which I think is part of what love is all about getting beyond one's own sense of separate isolation.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 23:41: That’s interesting, Richard, because as I see it, you’re taking the human predicament, which each religion in a sense has its conception, sin, or not realizing you're the same as the Brahman, or the Buddhist you believe the substantiality of things, you have to give that up and then you won't suffer. But your soteriology, to use the technical term, you know what's the fundamental predicament. What's the fundamental predicament? And you're saying the fundamental predicament is that we’re “little bitty parts.” In your mind, I know the first talk I ever heard you give, Richard, was on radical evil, and in part the radical evil is the single individual thinking they can be the whole.

Dr. Richard Oxenberg 24:31: I find that message running through all the religions. You can see it in Buddhism, for example, with the legend that a seer prophesied before the Buddha was born that he would become either a world conqueror or a great spiritual sage. His father, a king, said world conqueror. But what always struck me was that these two different paths were actually two different ways in which human beings pursue the overcoming of their ontological contingency and isolation. So one way is to say well, I am dependent upon the world and that places me in this very vulnerable position, and so the way that I'm going to resolve that is to conquer the world that I'm dependent upon and now I can be in control of everything that I depend upon. And that's the path of world conquest. And I mean we're seeing that play itself out in our own politics, I think in America right now. People who have that sort of path, who never can get enough Elon Musk with his $400 billion or however much it is

Dr. Richard Oxenberg 26:11: But in any event, that's the path of world conquest, and all of the spiritual traditions basically say it doesn't work. You know you can't succeed because what you can never succeed in doing is making yourself God. You can never succeed in making yourself the ontological ultimate. No amount of conquering the world is going to satisfy, and that's why greed is sort of endless, because no matter how much you have, there's never enough. No matter how much of the world you've conquered, there's still more to be conquered.

Dr. Richard Oxenberg 26:49: And so the other path is the path of spirituality, rather than the path of conquest it's the path of communion, it's the path of entering into a communion relationship or a love relationship with the world beyond. And that actually requires, from a spiritual point of view, almost the opposite disposition of the world conqueror, because what is required is a sort of humility. You have to open yourself up to the other and come to an appreciation of the other, rather than trying to usurp the other into yourself. These are the two dimensions, the two paths that human beings are tempted to as a way of resolving what we might call their finitude, their contingency, their ontological vulnerability, and I guess most of the religious traditions will say that only one of those paths can actually finally work.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 28:08: Yeah, I mean, that's the powerful side. It's not just oh, we have a higher path and then you've got to be talked into well, what makes it higher? And aren't we all relativists, or something like that? You know who's to make judgments, as the Pope said, who am I? But it just doesn't work. So you can be the most hard-headed practical person and say, well, you want the life of acquisition, of endless acquisition, consume everything you can find to consume. Well, that ends up with nothing. You end up with nothing. Because I often notice having a dessert you know, guilty dessert the first two or three bites are the best. By the time I get to the end it's kind of old, and so I've tried to train myself. Just have a bite or two and you'll have all the joy and not the cost. But you need to look at what works. And one after another, after another, you look at the biographies of the dictators.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 29:15: I've been reading some of that recently. Well, they all end up kind of miserable. In fact, Plato says nobody is unhappy as the tyrant. The tyrant has no friends and the tyrant has enemies. And Hobbes points out in his brutally realistic way nobody is so powerful they can't be killed in their sleep, maybe what happened to Stalin? There's a wonderful little comic version that's rather historically based, called the Death of Stalin. That's on Netflix or something, but it doesn't work, folks, whereas if you live a more loving life was one way to put it but a life that is willing to acknowledge everything, everybody and everything as their own intrinsic, having their own intrinsic value, you probably, if you're in a nice middle-class country, you know role in a country like America, you have plenty to eat and you don't need to eat and you don't need to boss this person and that person and the next person. You have your own little domain of autonomy.

Dr. Richard Oxenberg 30:27: And that’s where God comes in, not only as a lawgiver who says “Love your neighbor as yourself,” but there is something about our individuality we're not only finite facially, that is, we don't extend to the whole of what is right, but we're of course also finite temporally. We’re all destined for death. Death confronts us as cutting us off from being all together. Cut us off from any kind of relationship. in some sense, one might say that, you know, yeah, the world conqueror is going to die, but so is the philanthropist, I mean, the philanthropist isn't going to escape death either, but somehow, one of the things that I think religion is trying to provide us with is a sense of being connected with, or in communion with, that which is ultimate and eternal reality, that one can finally overcome the sense of finality that subjection to death brings, and that is also a kind of love that is required, in a sense, this is all summed up in what is called the great commandment in Christianity. “Love the Lord your God with all your heart and soul and might, and love your neighbor as yourself.” The one is a command or an attempt to get the person to experience a sense of communion with the eternal, with God, and the other is a communion with everyone else. So one is a vertical connection and the other is a horizontal connection and somehow, if you can achieve both of those, you will achieve what the Bible says is eternal life. So that's the path it seems to me that all the religions are pointing us toward in their different ways.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 33:18: In part because cultures are also particular. Not this religion is the one and only religion, although they seek that often and even to the point of violence and so forth, that's all an old story and maybe overtold, because there are other kinds of violence too, but each religion has to have– this is part of one thrust that I took out of God: An Autobiography. As you know, Richard, I was told to start Theology Without Walls that you need to recognize, okay, I'm pursuing, maybe loving my God with all my heart and soul and my neighbors.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 34:06: And the Buddhist is doing something else that involves deep meditation, and the Hindu something else, and there are others as well, and they're each achieving some kind of intrinsic value, or, as you would put it, Richard, connecting to the whole, or the eternal, the thing that's really real. That's the crucial thing, it's what's really real, and they're all doing it in their different ways, because what's really real can be, you might say, accessed or related to in a variety of ways. That's part of, you might say, the greatness of God, as I would tend to put it in my theistic language, but that's part of you might say, the greatness of God, as I would tend to put it in my theistic language, but that's part of the greatness of the ultimate reality is that it can be related to in many concrete ways, including, as we were talking, some of these humble ways like praying before a meal or just the shopkeeper trying to do a good job by his customers, being honest and delivering what he says he's delivering. Okay, that's part of—.

Dr. Richard Oxenberg 35:10: Even in the littlest moment of saying something rude to someone or saying something complimentary of someone, one the rudeness creates a separation between you and the other, and the compliment creates a union with you and the other. And that brings us back to the idea that every moment has its possibilities. Every moment presents us with the challenge of are we going to approach this moment as a world conqueror or are we going to approach this moment as a lover? And every moment can invite us to make one or another of those choices.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 35:58: Well, thank you, Richard. I think this is a very rich discussion and you've really thought through and, I can tell, thought through a lot of these things with your students, in kind of thinking through these issues with them, which is a powerful loving act when we think together rather than just thinking apart. We try to just - does this make sense to you? Can you use this thought in your life? And of course, that's what we're about with the Life Wisdom Project. Okay, I have a lot of speculative interest as a philosopher, but the bottom line is how does this affect your life and mine and what wisdom can we draw from that about how to live? And I think you've really contributed to that effort here today, Richard.

Dr. Richard Oxenberg 36:43: Thank you. It’s always a pleasure to talk with you about this, Jerry.

Scott Langdon 37:06: Thank you for listening to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. Subscribe for free today wherever you listen to your podcasts and hear a new episode every week. You can hear the complete dramatic adaptation of God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin by beginning with episode one of our podcast and listening through its conclusion with Episode 44. You can read the original true story in the book from which this podcast is adapted, God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher, available now at amazon.com, and always at godanautobiography.com. Pick up your own copy today. If you have any questions about this or any other episode, please email us at questions@godanautobiography.com, and experience the world from God's perspective as it was told to a philosopher. This is Scott Langdon. I'll see you next time.