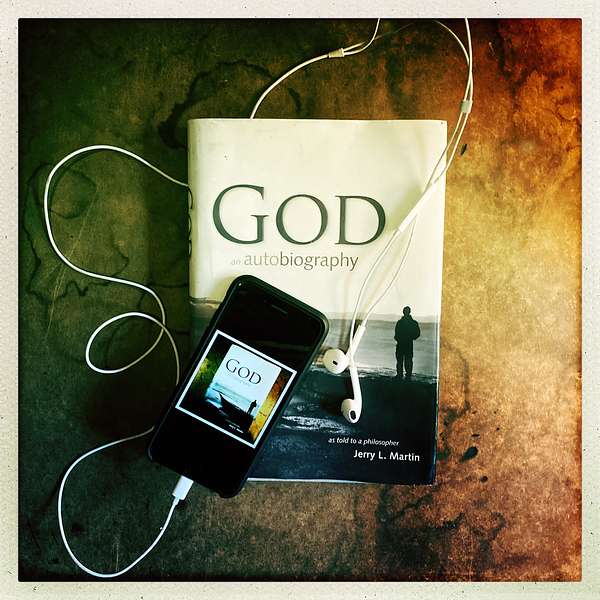

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

218. The Life Wisdom Project | Becoming Normal Through Love and God: Married Philosophers Journey Through The Story of Abraham and Isaac | Special Guest: Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal

In this Life Wisdom Project episode of God: An Autobiography, The Podcast, married philosophers and authors, Jerry L. Martin and Abigail L. Rosenthal, explore profound themes of spiritual growth, absolute obedience, and the tests we face in life.

Drawing on the story of Abraham and Isaac, they discuss how spiritual calls can be both enlightening and disorienting. Jerry shares his experience following the God voice and reflects on how moments of divine connection often feel both extraordinary and surprisingly normal.

Abigail brings deep insight through personal stories, including a poignant memory of a lost friend’s quest for meaning and the risks involved in following one’s inner calling. Together, they delve into the complexity of love, faith, and trusting your path despite uncertainty.

What does it mean to fully trust and act without hesitation? How can we distinguish between true spiritual guidance and illusion? This engaging conversation offers practical life wisdom through a philosophical lens, showing how we can navigate life’s challenges with clarity, courage, and openness to the divine.

Join us for this thought-provoking dialogue as we discover how moments of surrender and spiritual testing can reveal deeper truths about ourselves and our connection to a higher purpose.

Confessions of a Young Philosopher by Abigail L. Rosenthal

Other Series:

The podcast began with the Dramatic Adaptation of the book and now has several series:

- From God To Jerry To You- a brand-new series calling for the attention of spiritual seekers everywhere, featuring breakthroughs, pathways, and illuminations.

- Two Philosophers Wrestle With God- sit in on a dialogue between philosophers about God and the questions we all have.

- What's On Our Mind- Connect the dots with Jerry and Scott over the most recent series episodes.

- What's On Your Mind- What are readers and listeners saying? What is God saying

Resources:

Hashtags: #lifewisdomproject #godanautobiography #experiencegod

Stay Connected

- Subscribe to the podcast for free, and explore the book God and Autobiography as Told to a Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin, available on amazon and at godanautobiography.com.

- Share your thoughts or questions at questions@godandautobiography.com—we’d love to hear your story of God!

Share Your Story | Site | Facebook | Instagram | Twitter | YouTube

Scott Langdon 00:17: This is God: An Autobiography, The Podcast, a dramatic adaptation and continuing discussion of the book God: An Autobiography as Told to a Philosopher by Jerry L Martin. He was a lifelong agnostic, but one day he had an occasion to pray. To his vast surprise, God answered in words. Being a philosopher, he had a lot of questions and God had a lot to tell him.

Scott Langdon 01:14: Hello and welcome to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. I'm Scott Langdon and we return to our Life Wisdom Project series this week with a conversation between Jerry and Dr. Abigail Rosenthal, his partner in both philosophy and marriage, We always love having Abigail on the program and this time she and Jerry discuss episode 24. God Shares The Story Of Abraham And Its True Significance. The story of God and Abraham and Issac is a difficult one but if we probe the true significance of the story and examine our own lives through the lens of obedience to love, we might find some life wisdom along the way. This conversation between Jerry and Abigail does just that. I hope you enjoy the episode.

Jerry L. Martin 02:02: Well, I'm pleased today to have as my partner in this Life Wisdom episode my actual wife and philosophical partner, Abigail Rosenthal is her maiden name, and she’s the author of a remarkable book just coming out now Confessions of a Young Philosopher, using confessions in the same sense that Augustine and Rousseau use it. It's an account of one's life journey and search, you might say, for wisdom or whatever one is searching for in the profoundest reaches of one's life, and very happy to have that appearing on amazon.

Jerry L. Martin 02:52: And here we're looking at this remarkable part of the Old Testament, as those of us raised Christian call it, of God and Abraham, and I found the very opening that God is explaining interesting in terms of implications for daily life. It says most people, God says most people do not listen, they pay no attention because they don't want to. They're enjoying pleasures and using pain as an excuse for not paying attention. And what's remarkable about Abraham, God says, is when I whispered to him, he responded immediately. And I guess, when I generalize that lesson, there are two lessons here. One is pay attention, and I take that of course, primarily or ultimately to pay attention to God.

Jerry L. Martin 04:03: God is our witness and our partner, but pay attention to one's situation, to one's duties, to the people around you, people who may be in need, and don't just ride roughshod over them, for example. Pay attention to your situation and what you need to do and don't ignore it because you're off pursuing your own interest and don't use things as an excuse for not paying attention. And then the corollary of that is that God says Abraham responded immediately. And that's what we need to do. When we see ah, this is what I'm supposed to do in this situation, then do it. Don't say, oh, eventually I'll get around to that, or I'll put it on my what do they call it now? Bucket list- to-do list.

Jerry L. Martin 05:00: Yeah, anyway, did that strike you in a similar way?

Abigail L. Rosenthal 05:03: I hadn't thought of that. I'd gone immediately to the absolute dimension, the God dimension but I certainly agree about the promptitude, the urgency of doing the best you can do where you have a range of options in a testing situation. I fought to get a certain extremely pedagogically detrimental version of the Brooklyn College curriculum defeated with allies in that fight and I noticed that often when we had to deal with some higher official who had some power over the situation, my allies would tend to bring up concerns that were their own and perhaps legitimate, but very secondary or tertiary to the few minutes, few precious minutes where we had the attention of a person who could make a difference in our primary quest.

Abigail L. Rosenthal 06:27: So that funny distractedness from the main event is a feature of people. What you have from God is that their pleasures or their pains are an excuse not to pay attention to the main line of the action. Pleasures and pain, self pity or self-enjoyment. When I guess we're in a drama in life, whether we think there's a God who sees us or just we see ourselves, or however we visualize the watchers of our drama, it's obvious that you've got to be on cue. They don't give you a second chance when the play is going on and you have to say your lines at the right moment. There's only one right moment. So I certainly see the point of what you are getting from God. That has to do with knowing how to act. You're a consequential actor, whether it makes a little difference, a big difference or, to the best of your understanding, no difference, but you still have to act as if it makes a difference. How do you know what is the size of the difference it makes? So, yeah, I certainly see the point there.

Jerry L. Martin 08:16: Yeah, and it's got to be immediate. You can't just delay and halt around and a lot of that kind of I was thinking of these situations that you and I have been sometimes involved in. It's really a kind of not gross selfishness so much as a petty selfishness of just not being able to keep the eye on the ball. You know there's something at stake here, folks, and yet, oh, but I got this problem here. You know, blah, blah, blah. A little complaint. You know, I was snubbed three months ago and I'm going to yarn on about that and you need to lift your eyes.

Jerry L. Martin 08:55: I always think, too, about the highest thing you can see, whatever it's God or some other form of ideality or duty or the importance of the situation, the institution, the relationship. But whatever the highest thing is, keep your eye on that and try to use- you each have limited energy- try to use your limited energy- for the highest thing you can discern in your situation and pay attention so that if there is something high, you're noticing it.

Abigail L. Rosenthal: What I think is so instructive and constructive in the way you are translating back into human everydayness these words from God is that you are not taking the Akedah, what the Jews call the binding of Isaac, the sacrifice.

Abigail L. Rosenthal 09:55: You know the great test that Abraham is put to. You're not taking that as only something about us and God. You know, with a capital G, in an unusual situation, but a lot of people... What comes to mind is Soren Kierkegaard, you know, made a big story about the Akedah and I think he called it the teleological, that is, for a purpose, suspension of the ethical. It's unethical to murder your son. But for a higher purpose, if God says to do it, Abraham is ready to gird up his loins and trek up the mountain and do it.

Jerry L. Martin 10:45: Let's pause a moment and just tell the story. Not everyone has this at the feet of their minds. You know the Akedah that you know, and so forth, but what happens to Abraham that makes this moment of high drama?

Abigail L. Rosenthal 11:00: Yeah, God says to Abraham yoo hoo, Abraham? It's me, God, take your son, your only son, whom you love, and bind him and sacrifice him to me, God. And Abraham has waited about a hundred years to have a son, after, in the original Lech Lecha, get the up and get the out from Orde Chaldess and I’m going to make you my own, says God to Abraham, One of the other things God says immediately to Abraham is I'm going to make you a great nation and you're going to have many descendants and you're going to make history, you're going to change the planet. So, the son for whom Abraham has waited trustingly a hundred years until he reaches that age to have, is the one to be sacrificed.

Jerry L. Martin 12:10: No great nation can come. Yeah, this is the promise God made of it, make you like the stars in the sky or something. No it's going to be zero.

Abigail L. Rosenthal 12:22: Zero. And Abraham does not say wait a minute, it says here, I got it in the good book, I wrote it down at the time: You're going to have in your progeny and your descendants an enormous wealth of population going to come from your son. And oops, that very connecting link to the future cut off. And so that's what Abraham consents to. And he takes Isaac along with him and they climb up to the top of this Mount Moriah place and he ties Isaac. Oh, Isaac says what about a sacrifice? We don't have an animal. God, says Abraham will provide the sacrifice. And they get to the altar where the sacrifice is to be provided, and, to Isaac's perhaps surprise, he's the sacrifice.

Abigail L. Rosenthal 13:23: Abraham binds his son to the altar. The Hebrew for that moment is the Akedah, the binding of Isaac, of the binding of Isaac. So, no, running away, you are my boy, the sacrifice. And Abraham raises his cleaver, or whatever you know weapon he has to plunge it into Isaac, to plunge it into his son. And the voice of an angel intercedes and says stop, stop, don't do it, don't lay your hand on the boy, because you have been willing to sacrifice what is most dear to you on earth. I know that you are worthy, or you've passed the ultimate test. So that's the Akedah, the binding story of Isaac.

Jerry L. Martin 14:23: Yeah, of course I say in my dialogue with God if You told me to do that, I wouldn't do it. What can possibly be the point of such a story? And God says, no, of course I wouldn't do it. The purpose of that extreme example is it was necessary to drive home the point. And the point is God says the absolute authority I hold. And that's puzzling. It sounds kind of arbitrary, right? Sounds kind of arbitrary.

Abigail L. Rosenthal 14:57: Yes, it does.

Jerry L. Martin 14:58: Yeah.

Abigail L. Rosenthal 14:59: In Kierkegaard's version of that story what typifies or exemplifies the faith that Abraham has in the God he has followed out of his native city is he secretly knows that God will not follow through, and I think that's wrong. That can't be the right reading of the story, I think and Kierkegaard might have been interested in it because he calls it the teleological, that is, purposeful suspension of the ethical, and I think Soren Kierkegaard is thinking of his own case, where he breaks his engagement to Regina in order to become Soren Kierkegaard and kind of ruins her emotional life and probably distorts both of them. But if I'm reading this somewhat at a slant, but accurately Kierkegaard's Akedah provides a rationale for the way he mistreats his fiancée.

Jerry L. Martin 16:22: He's looking for a story that will justify breaking one's ethical duties, doing the wrong thing ethically. Any holy person can say well, I'm above all that right. It's a problem sometimes with gurus and everybody else, Evangelists and so on, that they, oh well, we're above that or there's ultimate forgiveness anyway, you know. So we can be ruthless or whatever. We are indulgent. So that's one thing to avoid doing.

Abigail L. Rosenthal 16:59: Yeah, it's a rationalization.

Abigail L. Rosenthal 17:44: If I try to get in the mind of Abraham or any analogous situation I've been in and I guess for me the analogous situation, oddly enough, was my sense that I had fallen hopelessly in love with you, darling.

Jerry L. Martin 18:21: And why would that be analogous to hey, go sacrifice your son

Abigail L. Rosenthal: Well the thing was, I had a good situation in life. I was a professor of philosophy at Brooklyn College. I had a studio apartment in the best neighborhood in Manhattan where I, as it happens, grew up and I was paying old rent and I was near all the museums and tea houses I needed to be near and I didn't need to fall in love. My life was okay, it was in balance for once. And all of a sudden into my life comes something that had a binding, Akedah-like, you know, impact. And it wasn't that I thought, as actually happened, I would have to give up all the things I've just described for us to make a life together.

Abigail L. Rosenthal 19:03: I didn't think about you know the ABCs of the situation, the particulars of what we'd have to work out to be together, to be together. I just thought I need to be above this so that I can look at it dispassionately, and I used a certain technique that is used sometimes in phenomenology, where you sort of just contemplate something, suspending its real-life consequences. I thought let me look at this dispassionately and all of a sudden, dispassionate looking, was over. I understood oh, I'm over my head and at that point, of course I'm a free being, as we are, I guess, and you know, unless we've done something so consequential that we're in the grip of that. But normally we have choices, even when something overwhelming happens. I certainly had a choice, but I understood the situation, no matter what the consequences. This is kind of an ultimate summons and I cannot take myself seriously unless I understand that this is serious. That's as close, even though everybody would say, hey, this is good news, this is a joyous situation.

Jerry L. Martin 20:49: No, it's not that simple. I think that's a very precise analogy to the... I hadn't thought of anything like that, but as I was pondering the language here, what God says is needed is for the spiritual... It's needed not because God has weirdo commands and He's got to say jump three feet, we jump three feet. It's not something stupid like that. But if the spiritual development of the world, this is God speaking, “The spiritual development of the world requires absolute obedience, total yielding,” and He goes on, “it's a matter of principle. Anything held back, even for the best of reasons, is a sacrilege, a defiant act.” And that's a really kind of spiritual vision. And I think falling in love is also a kind of spiritual act. You're drawn by spirit to, well, what God wants you to do. Okay, God, we're partners, we're going along, we're singing a harmony together, and so, okay, this is what is needed. Then we'll figure out the details later, we'll let the situation unfold and just being true to what seems like the draw, the valid draw.

Abigail L. Rosenthal 22:12: It seems like, you know, there was only one countervailing possibility and that's I've gone nuts. You know, maybe I was nuts. You know, sometimes you can feel an overwhelming call, or we know such cases and you're nuts. You know, sometimes you can feel an overwhelming call, or we know such cases and you're nuts. That's why it overwhelms you, because your sanity is gone. I didn't think I was nuts, you know. I guess I could have been wrong, but so far as I could tell I was normal.

Jerry L. Martin 22:47: Well, I had that when I followed the God voice, I thought this is weird and nothing could be easier to be mistaken about. Well, falling in love, would it be the other thing easy to be mistaken about? People get swept away. They're infatuations. It's a well-known phenomenon and yet, when love comes your way, there it is. And the God voice came my way and it seemed pretty clear. I was not crazy. I was the same person I'd been before that, right. Maybe I was a little quirky always, but if I was sane before, I was still sane, and you must have had something like that. It didn't seem as though you'd suddenly become a bizarro person, you know.

Abigail L. Rosenthal 23:43: No, but one can be wrong, for some reason the image of my lost friend John Armstrong comes to my mind now. He was a friend from my Fulbright year in Paris, and John wanted, he was an American boy of Scotts ancestry and he wanted to prove his own mettle, and so he thought, one way to test his character do I really believe what I think I believe, or do I have to sacrifice my values to get through? He wanted to go with two other boys. He kind of talked them into it on a trip from Egypt to the Cape of Africa, all the way down the continent, down the continent. And he wanted me to introduce him to Richard Wright, the writer in exile in Paris who knew something of Africa, and for advice. And I arranged that and Wright told John not to go. He said they'll never get past Egypt.

Abigail L. Rosenthal 24:56: John wrote his mother: tell me anything, but don't tell me not to go. And I've always… I didn't tell John not to go because I sympathized, I identified, you know, I empathized with my friend, but somebody should have. Well, Wright did tell him not to go. Anyway, there are cases and that's the one that right now comes to mind where you can feel an overwhelming need to do something x, whatever that is, and apparently you're wrong, you know. So there's an uncertainty here, which I think is unalienable from these tests, these spiritual tests, you really, by the world's standards, you can't quite be sure.

Jerry L. Martin 25:51: Well, what you can do and I think your friends did this for you and I handled this question in a different way and maybe failed to do it a bit, except for Richard Wright with John Armstrong, is they can point out the hazards. I think your friends did that. They point out the hazards. Look, you've got it good, you can have an affair. You know, you can keep your professorship in your apartment in Manhattan.

Abigail L. Rosenthal 26:16: My colleagues. I went to the people I knew in sociology department and psychology department. I thought you know, let me take a survey of the wise heads in my immediate environment. And they all said no, no, no, you know this, you'll recover. This is madness. Enjoy it, but stay planted in your good job and your good apartment.

Jerry L. Martin 26:37: In fact we lived in two different cities and in fact you came. We could have had a weekend affair kind of thing with Amtrak back and forth, but you made the decision right away not very much like the guidance here not to hold back, I noticed I didn't have to talk you into coming living with me in Washington DC where I was. You did not relish that, it's not a great city like New York, but you were willing to do that and you know, jump in with all four feet. I don't think you were reckless, you were never reckless and I think of my following the God voice.

Jerry L. Martin 27:31: You know, if anybody told me I was crazy, I would have taken that seriously. I talked to some old friends about it, consulted various, some of the wisest people I knew. I'm thinking of Leon Kass, for one, Michael Novak. You know people who knew this aspect of life, this spiritual aspect, and they were very helpful and nobody said you're crazy. They did say whoa, that's interesting, you know.

Abigail L. Rosenthal 27:57: I felt when you told me what had happened it's funny, but my feeling was now, at last, you're normal.

Jerry L. Martin 28:08: Yeah.

Abigail L. Rosenthal 28:09: Isn't that funny.

Jerry L. Martin 28:10: Well, it is funny and it isn't because you know, I would have said it was. I would have been the same way had I been in your position and I would have. No, I guess. No, I would have been skeptical. Had I had any friends reporting this to me, I would have been completely skeptical. But now I kind of understand you might say the human animal rather differently, and I understand us as somehow essentially oriented to, somehow connected to the divine and the ultimate and the highest, where somehow our system is somewhat aspirationally built toward you might call it just our ideal self, the self we would like to have. Economists who like to talk about every value in terms of preferences you have preferences. They talk about the preferences you would prefer to have. Those are the highest preferences.

Abigail L. Rosenthal 29:09: Plato thought so too. The just man, his sort of imaginary concept, who remains just while they put his eyes out. They defame him and everybody believes the slanders. That's, for Plato, the norm.

Jerry L. Martin 29:31: That's the norm.

Abigail L. Rosenthal 29:32: Yeah.

Jerry L. Martin 29:32: And it's built right into the human structure and the structure of reality. You might say yeah. I did become oddly enough, more normal. And maybe when you fell in love, you became more normal, you know, because it wasn't a mistake. If it had been a mistake it might have created distortions, you know, but it was not a mistake.

Abigail L. Rosenthal 29:58: I noticed I was seeing things, crisp, that had been blurry and assembled in proportion, that had been differently ranked, you know, uh, ranked according to how, uh, they scared me, or something like that. I, I saw the world in a way. It seems to me more true, and I noticed this early. You know, this looks super normal, super normal, right yeah.

Jerry L. Martin 30:40: And that's good, yeah, to be super normal is great. To be normal is enough, but to be super normal is great.

Abigail L. Rosenthal 30:45: In fact, I think I had a dream where there was a sort of august figure, female with long robes, Greek robes I'm vaguely remembering this just now who said to me you are absolutely normal, which sounds like a contradiction in terms. Normal is always qualified.

Jerry L. Martin 31:10: I have normally normal.

Abigail L. Rosenthal 31:13: On all sides. You don't go to extremes when you're normal, but apparently there's some kind of extreme that's inbuilt in normality itself, and when you're wholeheartedly in love, for example, you would be touching that kind of normal.

Jerry L. Martin 31:34: Yeah, isn't that great.

Scott Langdon 31:47: Thank you for listening to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. Subscribe for free today wherever you listen to your podcasts and hear a new episode every week. You can hear the complete dramatic adaptation of God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin by beginning with episode one of our podcast and listening through its conclusion with Episode 44. You can read the original true story in the book from which this podcast is adapted, God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher, available now at amazon.com, and always at godanautobiography.com. Pick up your own copy today. If you have any questions about this or any other episode, please email us at questions@godanautobiography.com, and experience the world from God's perspective as it was told to a philosopher. This is Scott Langdon. I'll see you next time.