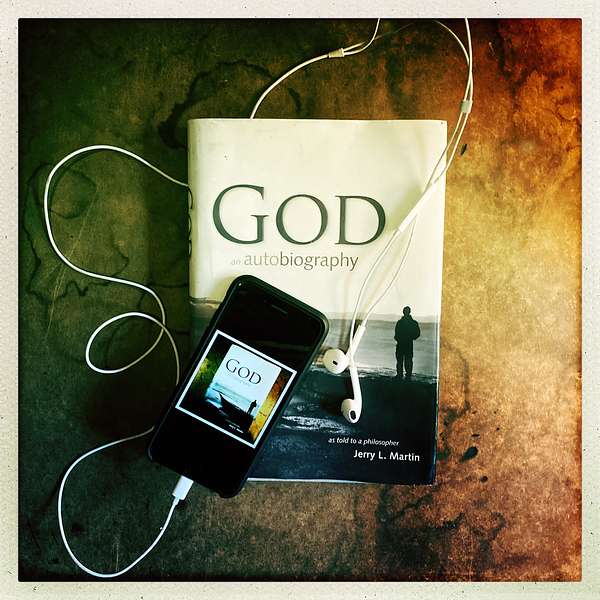

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

223. The Life Wisdom Project | From Ritual to Reason: A Journey from Plato to Levinas | Special Guest: Dr. Michael Poliakoff

How do rituals, traditions, and philosophical reasoning shape our understanding of the divine and the human experience?

In this episode of God: An Autobiography, The Podcast, Dr. Jerry L. Martin and Dr. Michael Poliakoff explore the evolution of thought and tradition from ancient Jewish practices and Egyptian influences to the philosophical insights of Plato, Aristotle, Confucius, and Emmanuel Levinas.

The conversation examines how humanity has sought wisdom across cultures and eras—from the Torah’s laws to Aristotelian virtue, Confucian ethics, and Levinas’ concept of “the other.”

How do ritual and habit shape moral understanding? And what happens when tradition gives way to reason?

Key Themes in This Episode:

- Ritual and Ethical Evolution – From Jewish law and Confucian rites to Aristotle’s philosophy of virtue

- Jonah and Nineveh: God’s Call Beyond Borders – What it means to be “chosen” and how divine purpose extends beyond any single tradition

- Levinas and the Ethics of the Other – How encountering another person transforms our understanding of self and morality

- The Power of Tradition in Daily Life – From religious rituals to simple habits, how they shape human interaction and spirituality

- Breaking Down Borders: Ancient Thought and Modern Philosophy – How wisdom from across cultures connects in the search for meaning

This episode presents a rare exploration of how ritual and reason interact—not just in religious practice, but in the very fabric of human thought. Whether you're interested in philosophy, history, or spirituality, this discussion offers insights that transcend time and tradition.

Other Series:

The podcast began with the Dramatic Adaptation of the book and now has several series:

- From God To Jerry To You- a brand-new series calling for the attention of spiritual seekers everywhere, featuring breakthroughs, pathways, and illuminations.

- Two Philosophers Wrestle With God- sit in on a dialogue between philosophers about God and the questions we all have.

- What's On Our Mind- Connect the dots with Jerry and Scott over the most recent series episodes.

- What's On Your Mind- What are readers and listeners saying? What is God saying

Resources:

Stay Connected

- Subscribe to the podcast for free, and explore the book God and Autobiography as Told to a Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin, available on amazon and at godanautobiography.com.

- Share your thoughts or questions at questions@godandautobiography.com—we’d love to hear your story of God!

- 📖 Get the book

Share Your Story | Site | Facebook | Instagram | Twitter | YouTube

Scott Langdon 00:17: This is God: An Autobiography, The Podcast, a dramatic adaptation and continuing discussion of the book God: An Autobiography as Told to a Philosopher by Jerry L Martin. He was a lifelong agnostic, but one day he had an occasion to pray. To his vast surprise, God answered in words. Being a philosopher, he had a lot of questions and God had a lot to tell him.

Scott Langdon 01:11: Welcome to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. I'm Scott Langdon, your host, and this week on a brand new edition of The Life Wisdom Project, Jerry welcomes back Dr. Michael Poliakoff. In this episode, Jerry and Michael have a beautiful discussion about Episode 25. I Ask About God’s History with the People of Israel. Michael always brings such beautiful insight into the Jewish tradition and in this discussion about God and Israel, he and Jerry share their thoughts about what God continues to be up to, as he calls us to look deeply into the other. Here now are Jerry and Michael. I hope you enjoy the episode.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 02:02: Oh hello, Michael.

Dr. Michael Poliakoff 02:04: Hi Jerry.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 02:06: I can see you, I can hear you. This is great, I think. The episode you and I are going to discuss, try to see what the life wisdom implications are, episode 25, but it goes, I think maybe the longest episode in the whole thing that we're putting on podcast, which is excerpts- this is excerpts from three different chapters, going all the way from the Jews as slaves in Egypt crying out to the Lord, to Jeremiah and the prophets, and that whole drama. And then there's some other things where I'm asking about Ten Commandments-style ethics compared to Confucian ethics, which I'd also read and prayed about a little bit, I guess, by this compared to Confucian ethics which I’d also read and prayed about by this point. But anyway, I do think it's a very rich episode, rich set of communication, dialogue between me and God on these very interesting texts.

Dr. Michael Poliakoff 03:14: Yes, yes indeed, and I'm so glad you brought Confucius, or God brought Confucius into this dialogue.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 03:22: Yes, yes, Confucius, I always feel is the Eastern Aristotle, since I'm a big Aristotle fan and a Confucian friend I've gotten to know through American Academy of Religion, Bin Song agrees with me. He started reading the Western stuff and, wow, Aristotle, this is really great. So, yeah, Confucian as a thinker, I've always read, you might say carried by my side a bit the way I carry Aristotle's ethics by my side as my guide to how to live. That was all before my religious turn, but they're still awfully good even after you're talking to God, because God's working through all these things, but anyway, what struck you when I went through, I must have found a dozen things that I thought this is an implication, especially if you kind of broaden it a little. Most people don't have my sense of, my vibrant sense from my own experience of a personal God and God issuing commands and so forth, and so I always encourage people you don't have to have that, I have that and of course I believe it and so on but I always just encourage people to think of other sources of ideality. You know what's the highest you can think of, and of people you love, institutions, communities you care about, and think about what God says in reference to those things. Let them stand in.

Dr. Michael Poliakoff 05:01: I've been trying to steep myself more and more in the works of Emmanuel Levinas. Precisely for that reason, that we cannot be who we are without our embrace, our interaction, our understanding of the other. And it actually has an extraordinary application in a book by Bernard-Henri Lévy that I come to admire so much, called The Genius of Judaism. I don't know if you're familiar with that one

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 05:35: Abigail is a great fan of Levinas, whom she studied for years, been to Levinas conferences. She likes Levi and the what of Judaism?

Dr. Michael Poliakoff 05:49:. It's called The Genius of Judaism, the genius and this was part of Bernard Henry's movement from Barbarism with a Human Face, which was that great bestseller. And as he said, “I knew something was lacking,” and at that point he began to study himself with Levinas. They were very close friends, really until the end of Levinas' life, and in this book he embraces a new reading of the book of Jonah. Why Nineveh?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 06:35: Okay, but let me back up and then we'll come back to why Nineveh. But I think our listeners aren't all familiar with these people and I only read a little Levinas, but maybe you can just give us a one or two sentence statement of who Levinas is or was. He's now deceased, but he was alive during my lifetime.

Dr. Michael Poliakoff 07:00: One of several Jewish pupils of Martin Heidegger, who absorbed the method and the instinct to use phenomenology. Of course that was not invented by Heidegger, in a way to interpret deeply the traditions, and of course they broke with him. Hans Jonas and Levinas actually confronted him about the appalling way that he had so misused the traditions.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 07:37: Yeah well, he became a big Nazi. Right? A strange perversion.

Dr. Michael Poliakoff 07:49: And Levinas, of course, was an Orthodox Jew and digs deeply into the Talmud with very, very deep interpretation of its intricacies, and one of his great contributions is that what really can define us as not just religious people, but as people of God, is to understand that there's something within us that is not something that, even in philosophy that we can easily reconcile, I brought him along because I thought we might actually get to that.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 08:30: Explain a little, Michael, how the concept of the other emerges in Levinas, because I think it's very relevant to episode 25, in fact.

Dr. Michael Poliakoff 08:43: It's rather a rejection of Heidegger too, in a way that I find really quite brilliant. That being there, Dasein, the great Heideggerian term, is utterly incomplete. It misses the point without our connection to the other. For the value of everybody and I was going to read a brief passage, “This is desire for what is beyond satisfaction and which does not identify as need, does a term or an end, a desire without end, from beyond being disinterestedness, transcendence, desire for the good,” something that and Levinas does make the case that this is something that in rigorous philosophical examination, stands the test of that kind of scrutiny, but that it's something that really takes us outside the realm of the kind of logical steps that hitherto had been recognized and things like embracing the other, which are disinterested.

Dr. Michael Poliakof 10:08: They're not your authenticity as an individual, they are a real and deeper authenticity. That's an extraordinary breakthrough. And he goes on to say, “love is only possible through the idea of the infinite, through the infinite placed in me, by the more that ravages and wakes up the less, turning away from teleology and destroying the time and happiness of the end.” There's an immediacy and applicability there. That's just really quite wondrous.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 10:45: Yeah, and then you were about to mention before I wanted you to give this background about Levinas, who's an extraordinarily important thinker in the 20th century, and not just for Jews but for everyone, who's had a major impact because of this concept of the other and the human face. You see another. That's the phenomenology. You move around the world. What do you encounter? Well, you encounter people. And how do you encounter them? By their face, and you look into their eyes, you know and you see. Ah, and as you put it, Michael, it's not just me, it's not just my own, my authenticity, my personal authenticity, that's at issue here. That's radically truncated as an understanding of what you're doing in the world. You encounter the other, and there are whole other dimensions. You're about to move on to Bernard-Henri Lévy's raising the question in this most recent book, I guess, about Jonah. Jonah is sent into the whale and he's on his way to Nineveh. And they're unbelievers, right?

Dr. Michael Poliakoff 11:53:Yes, they're bad people. They're going to be the enemies of Israel. They're dangerous people, and Jonah knows this, and yet God pushes him to the absolute limit and then plays an educational trick on him. You worried about a gourd and you're not worried about the city full of people, and even that last line, “and many animals.” This is the God that I think is so wonderful in your conversations that God isn't owned by anybody, not even by all, but not even by humanity. God is so far beyond that. And the thing that I love about Bernard Henry's book it's not a recent one, it's been out for a while is that he really wrestles with this concept, this entire chapter.

Dr. Michael Poliakoff 12:59: What does it mean to be a chosen people? And of course, in God: An Autobiography, God makes it clear that He's chosen a lot of people. A lot of important viewpoints, and they actually align. It's certainly there are examples of it becoming corrupted and perverse and murderous, but at the essence, all are seekers and all of that is welcome. It takes me back to my Hebrew school days, the beginning of Pirkei Avot, which starts: all Israel has a place in the world to come, which sounds rather parochial, and the rabbis glossed it immediately. What that means is all righteous people have a place, be'olam haba, in the world to come, the universalist viewpoint, and Genesis makes it clear that human beings came before there were Jews. The Noahide Covenant is about what basic righteousness is, and so, once again, I admire so much your approach to religion without walls.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 14:23: Yeah, because God told me to go read these foundational scriptures, the ancient scriptures of all these different religions, including one well, it comes up here a bit, I think, of Egypt, but the scriptures of Egypt, the Zoroastrian thing, which has no living tradition because they kept being wiped out by armies that came through Persia. It was once a major religion, but only a remnant remained and they're rather walled up into themselves. But all of these religions, and then the question for me that I was guided to ask in prayer, was God, what were You up to with these people, with the ancient Egyptians, with the ancient Chinese and so on around the globe? And it turns out, what they record in the Scriptures was, you might say, the aspect of God relevant to them, you know, and that they were able to pick up on and make something of, and hence Confucius or the various other Chinese traditions are responses to the divine presence to them.

Dr. Michael Poliakoff 15:42: I just want to read one of the short passages from Bernard Henry's book, “Reading the Jewish text. Reading it as it should be read, is to generate a universal that is obviously not the extensive one of the Catholics or, upon reflection, the intensive or radiant one of Levinas, of which I too have often made use in my work. This is the other universal that escorts human beings on the path of their history and to the center of their substance. I propose to call by a new name the secret universal, because that is ultimately what the story of the treasured people is really about.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 16:27: Yeah.

Dr. Michael Poliakoff 16:30: I at times envy you being a philosopher, Jerry. I just had to kind of stumble into this piece.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 16:39: Yes, yes, yes, yes, exactly.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 17:10: Well, in terms of what I'm told in episode 25, were there particular passages that struck you?

Dr. Michael Poliakoff 17:17: Oh, a bunch of them, Jerry, but I circled a few. “Do not discount arbitrary rituals as mere behavior. Outward observance, when it reflects inner yielding, is useful and appropriate.” And that, of course, is so central within Jewish vision that we try, in our poor, mortal way, to make concrete the metaphorical and the visionary. Hence rituals like putting on the tefillin, where it says in Deuteronomy you shall bind them as a sign upon your hands and they shall be for frontlets between your eyes. That, to me, is a metaphor, but when one wraps the tefillin on the arm and recites that passage from Hosea, I will betroth you to myself in righteousness, it's a tangible, physical reminder. And so we do these things that could easily be dismissed as arbitrary, but they reinforce the things that are so very, very important. And people will have different rituals, that's, of course, writ large. But they are meaningful things when they are accompanied by a sense of kavanah, of intention. Why am I doing this? What does it mean? What are the values that I take from it?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 19:05: The example God gives to me is a very simple one. The Confucians also had this heavy emphasis on ritual, but the example God gives to me is sending a thank you note. One can think of the courtesies of life. Those are little rituals, aren't they? When you offer someone else your seat, or you place the elder in the family at the head of the table, or you know, they're all kinds of just good manners, you offer food to someone before you eat it yourself, you know, and these are these courtesies of life and they occur in business and with next door neighbors and so on, are not trivial, but they're almost, well, I started to say the glue, but that's not adequate because it's dynamic, you know, they provide a lot of the energy toward our, you might say, idealized selves.

Dr. Michael Poliakoff 20:10: As you know, Jerry, I'm way too busy now. I have no control of my life, but one of the things I do each day is I get off at Farragut West and walk to the office of this organization that you founded with such insight in 1995, 30 years ago.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 20:33: It's a long time ago and it's so wonderful that you're carrying it to greater heights than I could have even imagined when we started with a three-person office.

Dr. Michael Poliakoff 20:44: You laid a brilliant foundation and I just put some furniture into it. But as I walk down Connecticut Avenue since I'm kind of a schlumper and don't you know, I haven't blocked out that time to pray quietly in a quiet place, I take literally again from Deuteronomy and these words shall be in your heart you talk of them when you sit in your house, when you walk along your way. And so as I walk down Connecticut Avenue, I take some moments to thank God for this extraordinary world and the extraordinary privilege of living in it, and to pray that I can be a good steward of it, that I can live up to these extraordinary gifts that have come to us. As it says in Jewish prayer, every season, every day, every hour. And the moment we lose that gratitude, we slip into this selfishness that our authenticity is us, rather than recognizing the face of the other, the spiritual gifts that have been given to us and the obligation to develop those things.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 22:14: I was talking about David from the Old Testament. Skipping through the New Testament, you might say. David is all too human, but understands power, has ample personal skills and is willing to fight and he feels the pull of the Lord and that is his challenge, his challenge, the challenge of David, not to indulge himself and appropriate his talent and opportunities solely for himself, but to use them for me and, we might add, as we're drawing life wisdom, for everyday use, to use them for somebody, to use them for other people, for communities, for institutions we care about, for values that are abiding, you know are more than just my values, what I care about today, but are more abiding than that. To use your talents and the other gifts that you know, this situation you're born into life, and the opportunities that gives you, to use those for these various wonderful purposes way beyond just your own self-indulgence.

Dr. Michael Poliakoff 23:30: Exactly, and of course it touches base with a beautiful prayer in the Jewish daily liturgy, “Blessed is God who endowed humankind with reason,” and obviously what follows from that is the obligation to use that wonderful gift.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 23:59: Yeah, no, it's just reading an interesting article on the two Abrahams. It's called by Adam Kirsh in the Jewish Review of Books, that a permanent part of you might say Jewish existence is, on the one hand, the Abraham of faith, and you know, one always has to be faithful in ways that often don't seem to make sense. One of the hostages just released a lovely woman kept kosher, wouldn't eat food that was not kosher, and kept the practices under these horrible conditions, under tunnels and so forth. And so one has to do that. You have to keep to what your personal ideals are, and if it's Jewish, there are a set of practices she has inculcated that maintain her Jewish existence and thereby a constant relationship with God.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 25:02: I had friends they're Catholics who said early on when I was having these experiences and I was talking because the couple was very helpful they knew a lot about spiritual life and they said, “I think about God all the time,” one of them said and I thought well, gee, I'm not really at all up to that. On the other hand, I then realized I kept reflecting on that Ah, there is a second way of having God in your mind. That's sort of like the way gravity is on your mind. You know you rarely explicitly think about gravity, but every time you step off the edge of the sidewalk or the porch, you know you're very aware of it, or look down from a tall building, you're very aware of it. Just well you keep your body upright by your body's awareness of which side—which way gravity pulls you. And in that way I am absolutely aware of God all the time. The rubric of my being—and not just the rubric of my being, but more intimately than that—the purposes of my life are intertwined with the divine backdrop, you might say.

Dr. Michael Poliakoff 26:21: There's a really beautiful Hasidic concept of sanctification, that sanctification of things that could otherwise be entirely secular. Your table can be a place where you just eat like any organism, or it can be an altar where you sanctify that act. A strip of leather can be something that you make shoes out of, or it can make tefillin.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 26:55: Yes.

Dr. Michael Poliakoff 26:55: And to think consciously about every act. Is this an act of sanctification? It is a wonderful way to view the world. I can't begin to say that I'm anywhere near it.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 27:13: But even for you and your moments of distraction because you're busy in the hurly-burly of the world, that's an ever-present awareness. I would guess that ideally if we would be sanctifying this moment a bit like that sense of gravity.

Dr. Michael Poliakoff 27:22: Even Connecticut Avenue with the sirens and the horns everything else can be a place that has a little bit of sanctification.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 27:40: Yes, that's right and so that's important to look for those opportunities in one's own life and especially to keep that background awareness and of what your own life's highest purposes might be. There's always the question something I emphasize in my new book, Radically Personal of what is my right path. Because you know, God is marking out the right path in the Old Testament for the people of Israel to develop this relationship. He's marking out their path. With Confucius and his folks He's marking out a different path and that's fine because that's also a divine path. But for a given individual it's more personal than that, because I started the organization you're now leading.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 28:39: At the time I felt this was the most the things I could do that would be worth my time and that sort of had my name on it. You might say this was the thing. And so I left whatever I was doing before and started this, started the organization you now run, because I thought I could make an important contribution there. In my own mind it's never I have to go change the world. You know young people tend to be very heady with that sort of global, you know, historic moment idealization. But no, most of our lives are in a smaller compass and the question. That's fine, it may be just getting your kids off to kindergarten, but you need to do that If that is the purpose you have at this moment, you know, in your unfolding story, with God as a benign presence and maybe partner.

Dr. Michael Poliakoff 29:42: I can only say absolutely yes, yes yes, yes.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin: Well, maybe that's a good place to stop. There's much more here, but these podcasts need to be kind of short and, uh, I think this has been very interesting, michael so it is.

Dr. Michael Poliakoff 29:58: I've never had a conversation with you, Jerry, that hasn't value. Value, the opportunity yeah, yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 30:07: Well, we haven't touched the full range of your scholarly background. I deal with the people in the religion community all the time because of my new work and they're bizarrely unaware and don't make use of the wisdom of the pagan world. And being a classicist, you know you're also steeped in that. They don't know Plato very well. They've usually read it the way you know a person does casually, Plato's in the background, the Stoics, they may not have read at all, you know. And these other sources of wisdom, the literature, they're somewhat aware. Everybody knows Oedipus, you know, but you know those are such rich sources.

Dr. Michael Poliakoff 31:00: They are indeed. If I may just go on for one minute more, Confucius, I just want to share my favorite analect, which probably was not from the pen of the master. It's just two characters.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 31:16: That's how these texts are.

Dr. Michael Poliakoff 31:17: I think it's in book 11, but I'm not quite sure of that. Born the same, habits differ. It's very Aristotelian. In the emphasis on the habits that shape you. There's a wonderful recognition of common humanity, and then the need for self-discipline and restraint and all of those other things that we've been talking about not very long ago.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 31:54: Yes, habits, and in Aristotle, virtues are habits, they're good habits. Basically, the honest person is habitually honest and it doesn't require a great act of will to be honest if you really have the virtue of honesty because it's your habitual behavior. That would be very in line with Confucian thinking and it seems very sound to me. And at a social level, traditions, traditions are the habits and if they're good habits, virtues of a culture, a civilization and important to keep going the way other good habits are.

Dr. Michael Poliakoff: Well, be well, my friend.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin: Thank you for fitting this in and I hope we haven't taken your last tiny modicum of strength here.

Dr. Michael Poliakoff 32:45: I could not think of a better thing to do on Shabbat after synagogue. Thank you for that.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 32:51: Well, thank you, Michael. You be well and we'll keep in touch, for sure. Okay, bye.

Dr. Michael Poliakoff 32:55: Bye.

Scott Langdon 33:17: Thank you for listening to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. Subscribe for free today wherever you listen to your podcasts and hear a new episode every week. You can hear the complete dramatic adaptation of God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin by beginning with episode one of our podcast and listening through its conclusion with Episode 44. You can read the original true story in the book from which this podcast is adapted, God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher, available now at amazon.com, and always at godanautobiography.com. Pick up your own copy today. If you have any questions about this or any other episode, please email us at questions@godanautobiography.com, and experience the world from God's perspective as it was told to a philosopher. This is Scott Langdon. I'll see you next time.