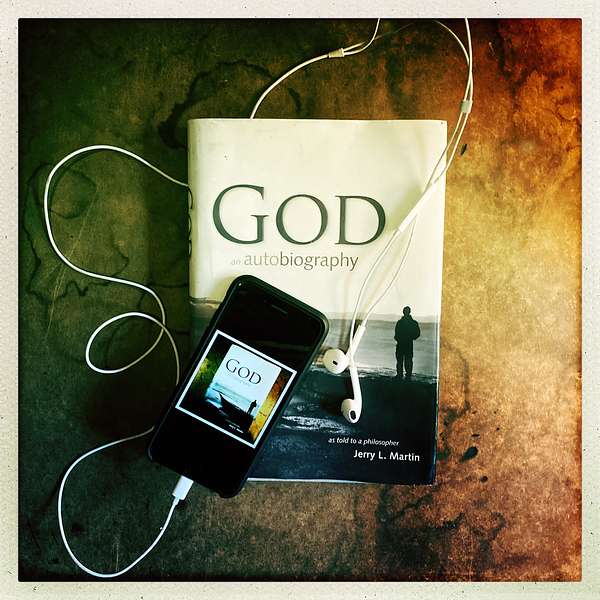

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

228. The Life Wisdom Project | Facing Divine Darkness | Special Guest: Matt Cardin

In this special episode of The Life Wisdom Project Jerry L. Martin is joined by acclaimed horror author, essayist, and religious thinker Matt Cardin for a profound exploration of divine duality, Zoroastrian cosmology, and the moral landscape of good and evil.

Together, they dive into God’s revelations to the prophet Zoroaster as recounted in God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher, unpacking a worldview where life is not a passive unfolding — but an active battlefield between light and darkness, truth and illusion. Through the lens of Zoroastrianism and Manichaean thought, the conversation traces how spiritual maturity demands we choose a side — not in tribal allegiance, but in moral clarity and existential responsibility.

Matt Cardin brings his unique background at the crossroads of religion, metaphysical horror, and philosophical inquiry to the fore. The episode confronts some of the most challenging spiritual insights from the book, including:

- “Most spiritually attuned people are not truth seekers.”

- “To look evil in the face is a spiritual act.”

- “My aspects have a life of their own and go wayward.”

These statements form the foundation for a dialogue about spiritual integration, shadow work, divine self-awareness, and the lived tension between peace and calamity — as illustrated in both Zoroaster’s vision and Isaiah 45, where God declares, “I form the light and create darkness.”

The episode also explores how horror writing, when used with spiritual intent, can serve as a radical form of not turning away — of confronting the hidden, the repressed, the divine and monstrous within. Cardin’s reflections on Jung, Freud, and the archetypal struggle for integration are especially resonant for seekers navigating complexity in both self and cosmos.

Whether you're drawn to Zoroastrian theology, psychological integration, or the spiritual function of horror literature, this conversation invites you to experience divine reality with open eyes — and a willingness to face the truth, however unsettling it may be.

Other Series:

The podcast began with the Dramatic Adaptation of the book and now has several series:

- From God To Jerry To You- a brand-new series calling for the attention of spiritual seekers everywhere, featuring breakthroughs, pathways, and illuminations.

- Two Philosophers Wrestle With God- sit in on a dialogue between philosophers about God and the questions we all have.

- What's On Our Mind- Connect the dots with Jerry and Scott over the most recent series episodes.

- What's On Your Mind- What are readers and listeners saying? What is God saying

Resources:

Stay Connected

- Share your thoughts or questions at questions@godandautobiography.com

- 📖 Get the book

Share Your Story | Site | Facebook | Instagram | Twitter | YouTube

Scott Langdon 00:17: This is God: An Autobiography, The Podcast — a dramatic adaptation and continuing discussion of the book God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin. He was a lifelong agnostic, but one day he had an occasion to pray. To his vast surprise, God answered — in words. Being a philosopher, he had a lot of questions, and God had a lot to tell him.

Scott Langdon 01:17: Hello and welcome to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. I'm Scott Langdon, your host and this week on the program, I'm very excited to share this conversation between Jerry Martin and Matt Cardin. Matt's expertise in horror fiction writing and his insight into the dark side of our existence made him the perfect one to call for this discussion on God's revelation to Zoroaster. The pair discuss several passages in the God Book that offer God's insight into what's going on with God's dark side and what God says about the ultimate order and structure of things in this world. Next week, join Jerry and me as we head to the email bag to find out What's On Your Mind. Here now are Jerry and Matt. I hope you enjoy the episode.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 02:02: Well, here we're trying to figure out, Matt. We're trying to figure out what takeaways there are for just listeners who aren't studying history of religions or any of this stuff and aren't even trying to at this point, trying to do a theological job of what's the nature of the ultimate reality or the divine. But how should one live? And I guess I was struck by a kind of bottom line. It comes toward the end, but it almost summarizes a lot of what had gone before: that life is a battlefield, you know, and an awful lot of religions are very placid, you might say, have a much more peaceful view of life, and you just let it be. You might say and accept that, but that's not the view that Zoroaster brings to it. It's life as a battlefield and we all have to just pick sides. In fact, that's almost a quote from Zoroaster's writing.

Matt Cardin 03:12: Yes, it is. I mean, and obviously Zoroastrianism is one of the primary world religious traditions that we point to when we look at that as the idea of life itself and the point of any religious consciousness, any spiritual consciousness, being to recognize that battle. I mean, we use the term Manichean, you know which actually (I hope you're not getting too much noise in the background here) which comes from the figure of money.

Matt Cardin 03:48: Who was, some significantly later, who lived and lived and taught significantly later than Zoroaster. But you know, he, as you know, he brought the Zoroastrian position and worldview forward several centuries and we've associated his name with it. When we talk about a manichaean battle or a manichaean scenario or a manichaean dichotomy, we're talking about an absolute opposition of light to darkness and good to evil, and definitely that's, that's been…

Jerry Martin: Except here, they're twins side and so that shows there are two aspects of the one divine realm.

Matt Cardin 04:40: The one God, and that is the part that is fascinating to get into. I mean, it's like you move further. It's a triangulation, right, you? You have, maybe you have the point at the top, and then you have the one angle going down to the right and the one angle going down to the left, to the twins right, but they're united at the top. I think I just kind of did a Trinity thing. I didn't mean to do that by invoking a triangle.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 04:56: My Christian friends, of whom almost all my colleagues have Christian roots in my work in American Academy of Religions, and everything comes in threes. And there immediately it can be water, ice and steam and immediately parcel out to the Father, Son and Holy Ghost. It's a deep, deep template that actually works for an amazing number of things. It's perfectly apt, you might say it does.

Matt Cardin 05:36: And in this particular case it certainly does. When you have the really sensitive conversation between you and God in the book you know is dramatized in the episode and through that dialogue you know God lays out, and Jerry, in the episode voiced by your partner, you know, in this endeavor, sort of keeps asking and understanding and say, oh so, so Zoroaster, uh, through his dedication to the truth, actually uncovered this, saw this, recognized this Angra Manu and and Ahura Mazda and, uh, and so God, this, these are actually both you, I mean. I mean I like the dialogue aspect, I really do, and I like the fact…

Dr. Jerry L. Martin: I'm a pedestrian philosopher, so what?

Matt Cardin: Dialogue. What are we talking about? Why? Would you do it as a dialogue? Where did that come from? But you it's great. I know it's something that actually came out of your writing of the book and you're interacting with God, but I'm just so… I don't want to what's the word I'm looking for here cheapen it by saying cool or good job or nicely done.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 06:55: Well, in fact, the book is almost a transcript. The first version was a transcript and Abigail read it the only person who read that version and she said hey, honey, the readers aren't hearing God, you need to put yourself in. And so I told how this happened and where it happened, and so forth. And then there was another version, and then readers of that second version, so far from being published, said what did your wife think? And so then I went back. She had not said much. So I went back and asked what were you thinking and why didn't you say much? And she said well, I thought something important was happening here and I didn't want to create, you know, static on the line. Well, that shows a very wise wife, for one thing and one. These spiritual things are sensitive and you have to respect that.

Matt Cardin 07:46: Absolutely, I agree. And by the way, that’s a far better response than the apocryphal about Robert Louis Stevenson who was deeply moved to write what turned out to be the strange case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, almost in this burst of not automatism, but this total eruption from the subconscious and as the potentially apocryphal story goes, his wife was so horrified by it that she burned the manuscript and he had to redo it.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 08:22: Abigail did not burn the manuscript, far better than that.

Matt Cardin 08:25: Far better than that, far better than the Stevenson story.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 08:28: Right. Well, what do you think life is a battlefield, or maybe a different way to put it is, one doesn't have to take that as the whole story. What can one learn from that?

Matt Cardin 08:42: I feel like the motif of life as a battlefield certainly works on a level and is what some of us experience, some of us more than others. I mean, it's real. In its own way, it is a real thing and I hadn't, it's been a while since I read the God book in full, some parts of it longer than others, and I reread the portions that we're here talking about and was struck once again by the level of depth to which the conversation went, to get to that point, you know, to see, oh, so we're talking about life as a battlefield, the subtle characterizations of the fact that no good is not just an abstraction and evil is not just an abstraction, these are really in human experience, these are coming from, these are expressions of realities, you know the of real realities in in the divine reality. I thought that's yeah, that's real, and so I myself, for example, my own experience, I know that I feel in my personal self-sense, I feel tasked with selecting between options, externally, and impulses within myself that do have a moral valence. They do have a moral, a good and evil, reality attached to them. The thing is, what I always circle back around to, and what I appreciate about the particular framing of an understanding of Zoroaster and his insight, in your book, is that, even that, even though that can play out on the human level, and even though I would say we are charged with living a life in which we make choices with that being the circumstance, that's the human circumstance, and we do live in an experience of duality where moral distinctions are not immaterial at all, that higher unity is important to recognize. If you don't, you're not recognizing something about reality.

Matt Cardin 10:58: And you had asked me to look through the text, and maybe identify some lines that I thought were worth drawing out. I can tell you that one of them is, that most, this is the line, “Most people, even spiritually attuned people, are not really seekers after the truth.” Even spiritually attuned people are not really seekers after the truth. And, of course, in the book, that is in the context, it has a wider meaning, of course, but it's in the context also of saying Zoroaster was, and that's why he could go to this level of depth in his understanding of the good and the evil of those twins that arise from the one.

Matt Cardin 11:46: I would agree that most people, even those who are spiritually inclined or attuned, are not exactly seekers after truth, and I don't remember the exact way in which the line develops further in the chapter that it's in in the God book, but it says something, the lines of, most people are more interested in a specific principle or idea or cause or something they can apply to life, to their life and their relationships and the practical reality of things, and employ that you know and and figure out.

Matt Cardin 12:23: You know within the field of their life, how to live, how, and that's not immaterial. But the truth itself, the truth itself, if you're really spiritually attuned, just beyond, say, being interested, perhaps even mainly intellectually, in religious things, the truth itself is going to take you places that make you uncomfortable and that go beyond any pat notions of what, good and evil actually are or appear like, and beyond pat notions of who and what you yourself are, and beyond the boundaries of whatever worldview you have been living in with and from through a combination of heredity and environment and what has been inculcated in you. Most people even spiritually inclined to people not being really seekers after truth yeah, I think we all try to live within some kind of sheltered view and we, reading that line, I think many of us who are interested in spiritual and religious matters would want to instantly assume well, that doesn't describe me. I'm really after the truth. In my experience and that of many other people whom I know and trust, yourself included, because I know that your own experience with these matters has been ongoing and profound and transformative unless you've reached something where your interest takes you to a point that actually shakes the foundations of how you understand self, world, cosmos, reality, how you even understand the truth, I think you haven't reached the point where you have matured into a real seeker after truth. Now, that departs from the specific focus on Zoroaster that we're talking about here, but maybe not, because Zoroaster was someone who it turns out that his actual clarity of seeking after the truth has us talking about him millennia after he was there, so it does relate back to that.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 14:33: Yeah, that's interesting. My sense is that and I think this is what God's gloss on most people are not seekers after the truth is that they've found some truth. The truth is that they've found some truth and mostly in life, you go along until you've found enough truth to satisfy you, you might say, and help you live your life oriented, help you come up with some coherent sense of things, you know what reality is like and what's important and what's less important, and there the search doesn't go on. The Socratic model is wonderful because one of the crucial things about Plato is he never sums up a final answer and you're always questioning. You're always questioning and finding a great deal of truth along the way of questioning.

Dr. Jerry L Martin 15:32: I just ran across I'd forgotten the lines, but a quote somebody was quoting toward the end of Plato's dialogue Gorgias. I'm going to tell you as Socrates is saying to Gorgias, Gorgias is a hopeless case, but I'm going to tell you a story and I'd like you to think of it as true. Well, that's a nice soft, you know, sense of… Well, take it seriously, take it seriously. Take it seriously and it's kind of the limitations of being a soul, a closed soul like Gorgias, but here I guess I take it more seriously. But I know you're a non-dualist and have other visions and there's always that thought you haven't gotten to the ultimate. I guess I'm not trying myself to get to the ultimate in that sense. No, I've been given one job, and it's a big job.

Dr. Jerry L Martin 16:33: It's really as an atheist friend of mine, one of the first long-time friend of mine, academic. When I just told him the basic story, he said ah, it's a revelation about revelations, and this is the age for a revelation about revelations in a way that maybe, well, I don't know. Certainly 50 years ago it wouldn't have made much sense, there wouldn't have been an opportunity to think that way. Now there's ample opportunity to think ah, we need to take in that larger picture and I always encourage people they don't want to go this far. Usually my academic colleagues take in your own personal experience. That seems to be an important part of the picture. It has to be. Yeah, that's where you sit and what you see, right?

Matt Cardin 17:35: When you say, take into account your own personal experience, I would focus on that and essentially not leave that. You and I have never known anything but our own personal experience. And yes, when we philosophize, and yes, when we theologize, we are trying to talk about in some way, to talk about reality itself, which commonly the consensus view of things wants, wants to, even if not articulate, even if just as an assumption is not to be found within that, or at least not wholly within that, not wholly within your subjective experience and it’s not a call to unwarranted solipsism, to point out and then to pause, more than just pointing out, to dwell in and to really dig into and to suddenly, sometimes with a hair-raising sense of, oh my God, feel a hair-raising sense of revelation and confirmation and maybe one of those moments I said, that rattles your cage, you realize that, for real, I have never known, I do not know, I will never know, I categorically cannot know, because knowing means knowing not anything but my own experience. And that, right there, immediately assumptions rush in and one wants to say, if you're brought up, say in the cultural context that I was, with the background assumptions of the worldview and the consensus reality, am I saying I'm trapped? Oh no, I can never know anything.

Matt Cardin 19:18: The problem of knowledge, no, that in itself is just a series of thoughts arising in my present experience. You mentioned that I, go for non-duality. Seriously that the fact of my present experience seeing you here on this screen and hearing your voice as we talk, and seeing and experiencing this physical form that I, for lack of a better word, call me sprouting out of the nothingness of the awareness from which I'm speaking right now, recognizing the thoughts forming and the emotions that both precede them and come after them, as I'm interacting with you like this and speaking, all of that this is taking place within the field of my experience. What else do I know? What have I ever known?

Matt Cardin 20:09: This is, this is what was there, and then I was given external, seemingly external, cues about what had to divide it all up and what to call it. You know when I read to bring it back, just, I know we can go anywhere we want with the conversation, but to think back to the Zoroastrian thing, it's very interesting how that's a story about recognizing a splitting, an insight into the twins the light and the dark twins from the one, because really that division is what begins to happen in every one of our personal experiences, at birth, right where we're faced with this just field of whatever it is that's undifferentiated at first and then the most basic distinction this is I, this is not I. The rest of everything I'm seeing is somehow not I, happens. And after that, the entire dictionary of categorizations we make of the different shapes that appear in experience. I find this to be endlessly fascinating. I think there's endless depth in it.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 21:37: Here again, think of how we're to live our lives. What God says about His own experience is my parts are not always well integrated. And when you think according to this vision, we have multiple parts and they're not all good. He says my own wisdom, He calls my calm center, assesses things, weighs them into balance, pacifies disturbances. And there is, of course, God says to Jerry, an analog for human beings. The story is not just a metaphor and it's really Me struggling to supersede other aspects of Myself and so on. So a lot of the story in a practical way is to not have your parts run amok. And I once heard somebody talk about cancer. You know a medical person on TV program. No, cancer cells are very healthy, they just run amok. You know they're just functional for the organism. Everything you know has its purpose, you know its role and you got to not let your separate parts urges run amok.

Matt Cardin 23:03: That's actually one of the three lines that I chose, from the chapter was the one where God says, “My aspects have to some extent a life of their own and go wayward.” Tons of insight, exactly what you're saying. Tons of insight packed into that and it, and again I keep. I talked about this whole subjective experience of things. When we're talking about these things, I find it necessary to relate them back to my own experience, not in a way to reduce them, but more in a way to expand the significance of what I am experiencing. These things that we're talking about we are not ontologically separate from. I don't think it's an idea, I think it's just a reality that God is in this way like us, that we are in this way like God, that actually it amounts to the same thing. We're not completely integrated. We have these roiling, competing energies and so on and so forth.

Matt Cardin 24:09: That is one of the primary insights to guide a life, you know, not just for God. And if we, if we recognize that in God, it helps. It helps when we recognize it in ourselves and vice versa, because if I'm not knowing, for example, and something as mundane as how am I going to get along with my wife when I get home tonight, you know how am I going to treat her? What am I going to- how has her day been? What am I bringing with me that I may not recognize in the way of any, if anything went wrong in my work day, or something like that, or what is she bringing with her?

Matt Cardin 24:42: Good Lord, it certainly helps, to realize that what's going on in this, in the cosmos, that we can see as this struggle between what appears to be a polarity in ethical and other ways of energies. It comes right down to the fact of me saying hello to my wife when I get home and finding out if there's something that's going to happen that I say, well, how did it go there? Well, that's what happens. You know, my aspects to some extent have a life of their own and go wayward. I can say that about myself just like God says it in the book.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 25:21: But it does help if, as you're doing right now, if you think before you go home. You're in a bad mood because we had a bad meeting, budget cuts, you know something bad and oh I can't… You can share that when you come home. But you can't bring the bad temper, you know, full-bodied home or it's going to be itself living a life, treating her as if she were part of this bad meeting, which she is not. She's doing something different and anyway you go through that period where you draw your parts together in a more functional integration. That battlefield sounds as if you're always fighting some horrible people. Well, the world has horrible people, but the most serious fights good versus evil is within oneself, God says. It starts with the internal conflicts and the integration is a way of resolving those by having your different conflicting parts lined up well in terms of the whole. In terms of the whole.

Matt Cardin 26:34: Absolutely. One thing that kept coming to mind as I was reintroducing myself to these portions of the God book was one of the passages from the book of Isaiah that struck me years ago. You know my background in horror writing and you know that—.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 26:53: Yes, yes, no, it's too scary. I've read some, very good stuff, but I can only read the tepid stuff. I can tell it's well done.

Matt Cardin 27:02: Well, thank you. Yeah, and thank you for letting me know I must be doing it well, because most of it is too horrible to read. And, as you know, it's for me for, for whatever reason, with the makeup of my psyche, and my activity. It's been, the bulk of my fiction writing has been, and even a bunch of my non-fiction writing, my essay writing, has been pursuing ever more refined and clear expressions of the intersection, or the nexus, or the meeting point of religion with supernatural horror and ontological horror, metaphysical horror, that kind of thing. It really consumed me for years and I knew that when I was younger, I think I've told you this, the sleep paralysis experiences with the hypnagogic experience of the demonic figures. Yes, that was transformative to me and that was coming after a childhood when at first my religion, that I was growing up in evangelical Christianity, was just rote, but then at some point I really woke up to it in my teens and I took it seriously. It was a possession of mine and I read my Bible and prayed and have done so off and on for years. But then I was equally, with helpless fascination, drawn to supernatural horror. Those kind of came together in a way in my writing as driven by these unplanned for, unplannable for experiences of seeming metaphysical assault over a span of years in my 20s and I was mining, non-christian, you know, other other world religious traditions and drawing great fascination and solace from reading about zen and, you know, advaita vedanta and that kind of thing.

Matt Cardin 28:56: But I kept reading my bible and so on, and when I came across a passage in isaiah that I seemed never to have read before, this just became like a I don't know a magnetic center for me for a while, trying to understand what's going on. It's Isaiah, 45, verses 6 and 7, and it has Yahweh speaking and He says, “There is none beside me.” You probably know the verse, “I am the Lord and there is none else. I form the light and create darkness. I make peace and create calamity. I, the Lord, do all these things.” And maybe I had heard it in a sermon or read it myself earlier in life, I don't know. But when it seemed that I discovered that for the first time in my twenties maybe I did at a time when my life was upended in various ways I just drew a whole lot of things together. I was also learning more about the Old Testament or Hebrew scriptures than I had before. I felt like I was reaching a more realistic and sophisticated understanding than I had from my tradition, and to see there in that long pre-Christian passage that there is no other power, there is just the Lord, there is just Yahweh, and He says in this canonical scripture no, I'm alone. Light, darkness both for Me, peace, or sometimes it's translated as blessing or wheel, and then calamity or war or chaos or woe, you know that kind of thing, those are for Me. I do all those things.

Matt Cardin 30:42: It just sat, it riveted me, it sat me up in my seat and it was coming to mind, as I said, as I was rereading the passages on the Zoroaster conversation from the God book. Because you know, I know the coming after the end of the episode of the podcast that deals with those chapters, it may be the very next chapter of the book that is, specifically, is titled something like the Old Testament is an answer to Zoroaster. So I thought I must have been remembering that or something when I was rereading and listening to these things and knowing that's where it was going, because this old verse for me was coming back. At the time I took it as sort of fuel for further exploring what came to be in some of my stories that I wrote, an interrogation into the potentially monstrous aspects of God in my stories, oddly, all this time later, when you and I were talking, before we really started having our conversation for the episode here, about my current creative hibernation, where I have announced to my online readers that I'm taking an indefinite break, and I'm detached from all social media and not publishing and not doing anything. I find these same verses from Isaiah to be greatly comforting with the insight that they express.

Matt Cardin 32:06: You know we were talking about the idea of God's aspects having a life of their own and going wayward and that being part of the Zoroastrian insight, the monotheistic Hebrew religious insight, the Jewish religious insight is, you see, disaster happening. You see chaos. You see what seems to be darkness and evil. You feel like, oh no, you know you almost start singing a Longfellow poem or something. You know I heard the bells on Christmas day and you know how wrong is going to win. There is no solace. You know there is no peace on earth, goodwill toward men. Wait a minute. This is all from God. God is holy.

Matt Cardin 32:52: Holy does not necessarily, especially in Isaiah, mean conventionally moral and ethical. It means categorically other. You know, the one that is unlike any other and therefore is of this essence that it is our place. And fearsome duty to fearful duty, to somehow learn to accord with reality. You know, God is the font of reality and so light, dark, good and evil. There's something about that that doesn't make God seem so, that doesn't incline me anymore to try and seek out the monstrous in God's nature and write fictionalizations of that in some kind of supernatural horror framework. Although that's legit, that's valid. I mean it's not like the viewpoint itself is outlawed or invalidated. Maybe it's just a different point in my life. I go, certainly as an individual, and me as Matt. My job is to do like God is talking about in the book find a way to integrate these things you know and find a way to choose and develop and maximize the good and the right.

Matt Cardin 33:59: The other stuff is not some absolutely alien enemy from outside. Anything that could possibly consider it something I have an affinity with. It is of God. Those things in me are of me. That's actually part of the integration process right there.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 34:17: What other passages had you picked out from things God said? God quotes.

Matt Cardin 34:31: There's a first and a second part, and the first part is the one I wanted to focus on. It's the same sentence, but, the part that says, it's a sentence from God again, not from Jerry in the book, not from you. “To look evil in the face is a spiritual act.” “To look evil in the face is a spiritual act.” Now, I like that excerpted by itself, because it's punchy and it could serve as a focus of fruitful meditation. The end of the sentence says that doing that looking evil in the face being a spiritual act, says “it requires being in touch with Me,” says God, “and looking, as it were, through My eyes,” which may draw right back to exactly what I was just….

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 35:16: The Isaiah insight.

Matt Cardin 35:19: Mm-hmm, it's potent stuff. It's the kind of thing that if one is drawn to words some people of a spiritual and religious persuasion or not, there are other things for them, great good. But for those who are drawn to, verbal expressions of things and finding them a way inward, you know, for spiritual depth and contemplation, dwell on that one for a while. To look evil in the face is a spiritual act. And then add it requires being in touch with God and looking, as it were, through God's eyes to be able to look evil in the face. Everything is suddenly drawn together, both metaphysically and morally, in our lives as beings who are called upon to try and find the way, to make a moral pathway through a sometimes confusing life.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 36:12: Yeah, I mean it's striking because you've got to recognize it as evil and that's what somehow it goes on to saying, I think God continues, otherwise you see it all bad childhood or you know, you explained it away in some way. But now, meanwhile, whatever the genesis of it, it's evil, it's evil and you've got to see it as evil and that's, as it were, through your divine eyes. You see, yikes, you know I was always disturbed by this theme that you warmed to, or at least at this point in life, warmed to Matt, and at one point I often quote this for some reason, so it obviously sticks in my mind I was saying to some of this kind of talk it sounds as if You're saying Lady Macbeth is just fine.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 37:02: God was saying the universe has to have characters like Lady Macbeth. And I said it sounds as if You're saying she's just fine, that she's okay. And God replies yeah, I said it's as if you're saying it's okay. He said, no, it's as if you're not listening to me. No, it is evil, it's wrong, it's bad. But in a world with organic creatures, with intelligence, desires, purposes, free will you know these kind of complexities, these beings, this kind of being is going to be capable of murder, and that doesn't mean murder is fine. But the universe, somehow, ...

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 37:53: I’m told at some point friction is essential to reality. We always imagine if you could have the plane that had no bumps in it, everything would just zoom. They first imagined with the airplanes, if you get rid of friction, they later learned they couldn't fly at all without friction. This is part of this complex reality that we and God live through.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 38:21: And then the challenge is to be truthful, to recognize that reality, to recognize our own participation in it, even maybe the way Jung likes to talk about, to accept one's shadow self, the kind of aspects of oneself you don't prefer.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 38:37: But rather than making them into Jekyll and Hyde speaking of Jekyll and Hyde and trying to parcel them out, you accept, which doesn't mean you don't try to say, oh, I've got to try to change this bad habit, let's call it. But you take it in that this is all this unseemly aspect of yourself. Instead of just diverting your own eyes from yourself, you take it in and try to—in fact, there's a wonderful prayer in the Jewish tradition Lord, you know they've got the concept of the evil impulse please let my—if I do evil, please let me serve higher purposes, you know, be turned to divine purposes, and so, okay, even there are things you can never change about yourself perhaps, but you can kind of hope that they work out in some positive way. The way, maybe, horror writing is a positive thing, even though there's a lot of parts one would want to divert one's eyes from there.

Matt Cardin 39:54: You know Ramsey Campbell is one of the great living horror writers. You know he's a British author, has won the Bram Stoker World Fantasy Award total genius and he is among those who have spoken pretty potently about horror being the genre that is devoted to not looking away, and there is that, there is a spirituality to that. That's kind of like Scott Derrickson. He's a Hollywood director. He's probably most famous now for having directed a couple of the Dr Strange movies, a couple of the Marvel Comics movies. You know he began by directing horror, including the Exorcism of Emily Rose, which is a very fine religious horror movie. He himself is a Christian prominently so, and has spoken specifically about Christianity very famously. Back in the aughts he talked about how he thought horror was actually the ideal genre for talking about religious and spiritual matters, kind of like in the same way that Ramsey Campbell talked about it being the type of storytelling about not looking away. It actually goes for right and wrong and good and evil and interrogation of what the nature of reality is. You know and I don't mean to make this into a side dissertation on a field that I've worked in for a long time you're reminding me of that, though, and when you talked about Jung and the idea of the shadow, we're in sync, because at the same time I was thinking of Freud and the desire, the very, astute, insightful principle that he articulated, although of course it had been around in other forms for essentially forever.

Matt Cardin 41:36: The return of the repressed, that which we do not, that which we repress, which we eject and refuse to acknowledge, is precisely that which is going to come back, you know, in some sort of nemesis-like form. I mentioned Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde earlier just because of that story about Stevenson's wife burning his manuscript. I wasn't really thinking about the fact that it's division of the human self into the light self and the dark self applying here. Didn't come in meaning to talk about that, but you know, you brought it up again and it does.

Matt Cardin 42:09: And really what happens in that story is that Dr Jekyll kind-hearted, brilliant, basically saintly, the best guy you could ever want, you know, best guy you could want to know or be because of that quality of himself had wanted to find a way to develop a drug or some technique that could purge humans of the evil side of themselves, and what it ended up doing was creating this dichotomy between them where, if you want to look at it this way, the whole story is a pre-Freud story of a return of the repressed kind of, or a letting loose, a liberation and unbinding of this dark side and so his attempt to eradicate it and and just write it out of his map of reality of himself in the world

Dr. Jerry L. Martin: He can be pure, but he's created pure evil in the world.

Matt Cardin: In the process, all he's done by unbinding it from himself is to give it this autonomous existence, like we keep talking about God's own parts going wayward.

Matt Cardin 43:18: It really is an astute story, both psychologically and, I would say, spiritually. And it's something that we're talking about right here, and it does go into the Zoroastrian model of things, where both twins have their legitimate reality, but there's also the legitimate question and answer of how to put it, which one we are to back. You know, accepting the reality of the evil does not mean accepting that the evil is fine. Like you said about Lady Macbeth. It's not saying and it's great, go ahead and do that, it's great, somebody, go ahead and be a mass murderer. Because you know that's real, and it would be foolish to deny it. On one level, yes, foolish to deny it. On another level, monstrous in its own right to champion that, or at least to not recognize the call. To greet that in the right way and try to develop beyond that, which is exactly what, in different language, God is revealing to you in that conversation.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 44:32: Yeah. Well, thank you, Matt, I will let you get on with your day. This has been a wonderful discussion, as it always is with you. You're a deep thinker who's read everything, as far as I can tell, and that makes it a pleasure, and you're a very good friend at long distance. We've never met in person.

Matt Cardin 44:55: I have cherished your friendship for years as well, Jerry. It's just strange, and in its own way charming, that it has developed through nothing but these long distance conversations for a long span of time.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 45:07: That's the way of the world maybe now. I just had two encounters, both Zooms, people I've never met that had a profound impact on me and you know I may never meet these two people but anyway the impact we may become friends, the way you and I have become long distance intermittent friends.

Matt Cardin: I hope, so.

Scott Langdon 45:39: Thank you for listening to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. Subscribe for free today wherever you listen to your podcasts and hear a new episode every week. You can hear the complete dramatic adaptation of God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin by beginning with Episode 1 of our podcast and listening through its conclusion with Episode 44. You can read the original true story in the book from which this podcast is adapted — God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher — available now at amazon.com, and always at godanautobiography.com. Pick up your own copy today. If you have any questions about this or any other episode, please email us at questions@godanautobiography.com, and experience the world from God’s perspective — as it was told to a philosopher. This is Scott Langdon. I’ll see you next time.