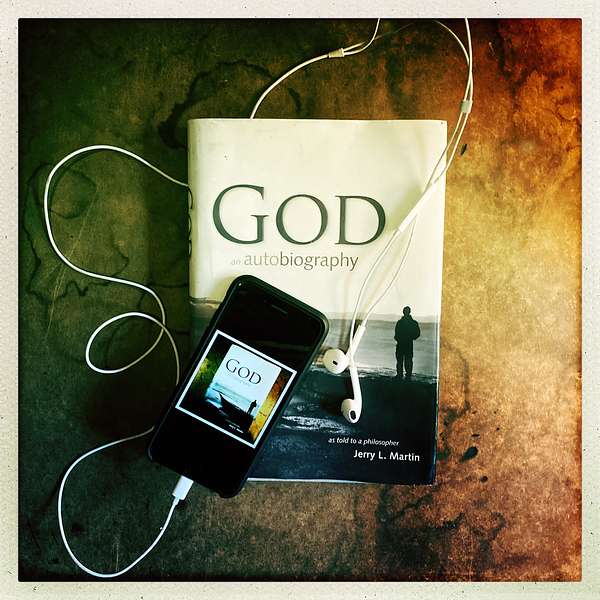

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

233. Jerry and Abigail: An Intimate Dialogue | Philosophers Answer: What Is Love

Welcome to the debut of a new series: Jerry and Abigail: An Intimate Dialogue, a conversation between two philosophers who are also deeply in love.

This is not just a love story. It is an exploration of what love means at the level of reality itself.

In this episode, Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal and Dr. Jerry L. Martin ask a question deeply human and spiritually profound:

What is love and what does it reveal about the nature of the world we live in?

Through personal recollection, philosophical reflection, and cultural insight, they explore:

- The stroke of lightning: Romantic love as a break in the surface of reality

- Why biblical love stories begin the work of God

- Rachel as the sine qua non of sacred history

- Love as an ontological force more than emotion, embedded in being

- Spiritual meaning beyond religion, through feeling, intuition, and integrity

- Cultural contrasts: European vs. American views on love, purpose, and compatibility

- The role of gratitude, authenticity, and moral seriousness in real connection

- What it means to live in a disenchanted world and how love re-enchants it

"Love is not a delusion. It is what moves the sun and the other stars.” – Abigail L. Rosenthal

Jerry and Abigail remind us that truth is not always found in the dominant worldview. Often, it comes from moments that break through: a glance, a conversation, a shared fight for something that matters.

This intimate dialogue speaks to those who live at the edge of conventional categories, those who are spiritual but not religious, seekers of meaning, lovers of wisdom.

If you’ve ever felt there must be more to love than psychology, more to life than surface logic, this is your episode.

Begin here. With feeling. With thought. With two philosophers, in love.

Other Series:

The podcast began with the Dramatic Adaptation of the book and now has several series:

- Life Wisdom Project: How to live a wiser, happier, and more meaningful life with special guests.

- From God To Jerry To You: Calling for the attention of spiritual seekers everywhere, featuring breakthroughs, pathways, and illuminations.

- Two Philosophers Wrestle With God: Sit in on a dialogue between philosophers about God and the questions we all have.

- What's On Our Mind- Connect the dots with Jerry and Scott over the most recent series of episodes.

- What's On Your Mind: What are readers and listeners saying? What is God saying?

Stay Connected

- Share your thoughts or questions at questions@godandautobiography.com

- 📖 Get the book

Share Your Story | Site | Facebook | Instagram | Twitter | YouTube

Scott Langdon 00:17: This is God: An Autobiography, The Podcast, a dramatic adaptation and continuing discussion of the book God: An Autobiography as Told to a Philosopher by Jerry L Martin. He was a lifelong agnostic, but one day he had an occasion to pray. To his vast surprise, God answered in words. Being a philosopher, he had a lot of questions and God had a lot to tell him. Episode 233.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 01:08: Well, here we are.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 01:11: Seems. So yeah, yeah.

Scott Langdon 01:19: Welcome to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. I'm Scott Langdon, your host. This week we debut a brand new series called Jerry and Abigail: An Intimate Dialogue. Since God: An Autobiography begins with a love story, who better to discuss that love story than the couple themselves? Jerry and Abigail have a unique love story and as they begin to contemplate that story in this discussion, their thoughts on the subject are both sweet and profound in equal measure. God is at the center. That much is clear. But no matter who you are or what you might think about God, the power of love and what it's capable of are experiences we can all relate to on some level. Here now are Jerry and Abigail. I hope you enjoy the episode.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 02:22: Well, hi, sweetheart, we're going to have our first dialogue, our new series, and the place to start is obviously at the start of God: An Autobiography. I often tell people about the book, it starts with a love story. And it certainly does, and so, as somebody said to you at some meeting where I was talking about this, they asked are you the love object? Right? Somebody came up and- are you the love object? And well, yeah, okay.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 02:58: Heavy, heavy. They say in the counterculture.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 03:04: Yeah, the striking thing for me is and I tell this is that I had not believed in romantic love, and yet this was deep, deep heels overhead romantic love. I was looking for compatibility, which a lot of sensible people do, you know, and that can make even a good life. You have the same hobbies and values and priorities and so forth. But no, this went way beyond that and so I ran. You know I don't understand this. So I ran to read the relationship books and I just found all they do is warn you it's not real. It's not real, it's projection, and I guess that for sure can happen. Many things like that happen to people. Nevertheless, this wasn't that, and I remember you know it's as if you go to a doctor and the doctor doesn't have any concept of a healthy body, just has a list of sicknesses, and so everything is wall-to-wall illness. And I remember thinking haven't they ever been in love? Because they just did not seem to know anything about the phenomenon they were studying. And so I thought well, women seem to be the experts in love. What do they read? Romance novels, love stories. And so I read one that I happen to have, and here's what I write on page three of the book, one of these romance novels, one had been left in the place I was staying. It was the first book that really told me about love.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 04:55: “Love is not a set of psychological triggers firing off wildly. In a sense it's not subjective at all, not a mere feeling. It is an ontological fact, a bond between two people that is deep within the structure of reality itself.” Now that sounds pretty over the top, and yet I think I would stand by that today. If you'd asked me years ago. I know this question came up my first year of grad school: what is love? Grad study first: what is love? I thought, well, it's a feeling, it's a certain kind of feeling. Well, it's not. It's deeper than that. Does that make sense to you, sweetheart?

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 05:42: Oh yeah. Well, my thinking on the interesting topic of romantic love was not formed by American psychologists or people in that life-world, in that mindset. It was really formed by European women, and I guess they're a medley of influences, partly…

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 06:21: Why European women? You're growing up in America, right? So how is it European women?

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 06:31: Well, my mother was European and her women friends were European, and I sat like a little acolyte at their feet and drank in their wisdom and put it together like puzzle pieces with some of the literature, I'd read, I guess in French class, the Romance of Tristan and Isault, which comes magically and suddenly it's called the Stroke of Lightning in French parlance. The only problem with it is either in the medieval story where they drink a magic potion and fall hopelessly and instantly in passionate mutual love, they can't live it. It's outside the boundaries of the social structure, so they live as outlaws and then they both die, which comes to the same thing modernized and updated. What the French believed is that it lasts a given span of time, after which point it's over. So they were of limited use, but at least they had the fact of something not exactly in the empirical stream of data, but something that interrupts that ordinary flow of experience.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 08:15: Then I had the biblical stories, where the lead characters, the first three patriarchs, aren't even set up to do the work of God until they've got the right partner. Abraham needs Sarah, Isaac needs Rebecca, Jacob needs though he has some other wives and concubines Rachel, and somehow in the Jewish imagination, although most of Jacob's descendants were descended from other women, Rachel stands out. The beloved wife stands out. She's the sine qua non. Without her there is no patriarch and there is no tribal history to follow. So that was another support from a very different direction, and it had to do with lasting in time and making an impact in the temporal flow of life and in what we call history. So I had every reason to be maladjusted in America and to take love absolutely seriously.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 09:38: You know, that's funny because I think the American attitude it's one of the great things about the American character is we're extremely pragmatic and it makes us feel, oh, there's no problem we can't solve. There's a tremendous can-do vitality that comes from that and we, of course, are an enterprising group of people and so we go all out in that dimension. But it's as if people had only surface and not depth. And my compatibility thing was kind of like that. It was a personality profile but it was extroversion, introvert, you know this, that and the other thing, and that's it. You know you encounter okay, let's check you off.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 10:32: And sometimes I know mothers who are ambitious for their daughters have often, whom I happen to know, are looking to position their daughters for success in life and send them to the best college where they can meet the best guy and then have the best life, you know. But that's kind of a calculation, as if you were starting a new business or something. But the European insight that you're talking about, the feel of love on the continent, at least in France, there's kind of a depth there isn't there? Because it comes like a bolt piercing the surface of reality.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 11:19: Exactly, it cuts through vertically the horizontal flow of things. So the problematic for the young girls we Fulbrights were when we went off to Paris was how to merge the uncompromised absoluteness of love, of romance, with ordinary life so that it would last. And the women who were in France, in Paris, with me in the year of my Fulbright, discussed that problem endlessly: how to capture in one real-life experience the absoluteness of the stroke of lightning and the continuity of real life so that they would merge.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 12:46: if what I read is right, it's not just a feeling, it's not just a stroke, but it's deep in reality. You find the right person. It's deep in reality and it's in those depths and you look at how I fell in love with you, sweetheart, it was at Brooklyn College, you know, because we had a splendid, award-winning core curriculum and a new president decide, oh well, let's junk that so that I can make my mark or something you know, it's just, they're often superficial in that way, I'm afraid. And you and the wonderful history professor, Margaret King, a very accomplished scholar and stout-hearted, you know, opponent of things that are bad rather than good, of things that trash excellence. And so the two of you took on the fight, called me at my office. You called me at my office in Washington. I still have the notes, I have them framed now because at that moment I didn't know how it would shape my life so decisively. But can you help? And I said that's what we do. And we fought it, talked daily on the phone, had to take it to the public and rally alums and everybody else, and we were talking daily because this went on for months, a fight.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 13:57: The administration that was pushing this through holds all the cards in these things. So you got to push very hard to get them off center. We did that and in the course of doing that, we had never met in person, but talk about depth rather than surface. I'd never seen your surface and I fell in love. Well, what did I fall in love with? I remember articulating it to myself you know you fall in love with a whole person, not with this or that trait.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 14:30: Nevertheless, certain salient traits came through to me and I would be interested, sweetheart, whether you can relate how I saw you to a self-understanding. Does it seem accurate, or was this itself projection? But it was two things. One was your moral earnestness. You really, in this case, what that meant was you cared about these students. You were not interested in faculty power or protocols or some cultural issue or this or that. You were interested in these young people and giving them a liberal arts education which would prepare them to bring some wisdom to their lives.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 15:16: And the other thing that struck me was your sensibility. You would often, after a faculty meeting or something, you'd call and give me a report and you would say do you want the black and white version you know the quickie report or do you want the technicolor? Well, I always wanted the technicolor, because your sensorium is such that you take in all kinds of subtle features most people wouldn't even notice in a situation or about a person, or about something you read. That's your sensibility that you bring to everything. Do you relate to those two descriptions or does it seem very surprising someone would think of you that way?

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 16:16: No, not a bit. Young people, you feel a terrific sense of the momentousness of having an influence on people young enough to be starting out in life, inhaling, ingesting the sedimentary layered treasures of the civilization we are standing on or in. And the other thing is I talk to young people as a teacher. I have to mean what I say. They can detect the phony. They are not necessarily idealists who expect anybody to be other than phony. At the same time they have a certain cynical contempt and weary familiarity when they come up against whatever, whoever they deem to be phony.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 17:28: It's kind of a street smarts, isn't it? Because it's not polished and refurbished, or fully equipped with learning or anything, but you're not going to talk them into something that isn't so.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 17:44: Yeah, maybe kids from the Ivy Leagues don't have this particular discernment or don't care so much about it, but on the streets in Brooklyn it's life or death. You really have to know what you're meeting and they have a phony detector that's in very good working order.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 18:10: So if you're going to tell them that philosophy is good for them, reading Plato is good for them, they can learn something from Socrates, you've got to believe that and you've got to act on it. I guess you're saying, you've got to not be a phony.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 18:24: Yeah, yeah. If you're a dance teacher, you've got to be in shape yourself, you know. If you're a singing teacher, you've got to know how to hit the high notes or where they are located, and if you're a philosophy teacher and you’re teaching, it's a love of wisdom, the accumulated savvy of the centuries in our civilization. And you're a phony? You don't really believe any of this? Well, no, they couldn't pay me to do that. I have to mean what I say.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 19:07: Well, that's a wonderful principle. As far as I can tell, you've lived that out and this question about what is love, you know, keeps coming up to my mind. Because love, love, love. You know, it's said all over. It's very prominent in God: An Autobiography at one point about love: why shouldn't that be the story of the universe? But I'm always worrying a bit, but what is love? Well, here's one answer: it's grounded in the depths of reality itself, when you're really in love with someone, and it's not just pitter-patter which it often sounds like, even in religious context. Well, what is it? It's kind of a nice color that swooshes across your screen. But is that it? And I remember telling you early on, I don't know if this made sense to you at that point, you are easy to fall in love with but hard to love. And I said that because I think this is the language of analytic philosophers.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 20:20: A category in their philosophy of language is an achievement verb. To love is an achievement verb. It's like the difference between seeing and looking. Seeing is an achievement word. You didn't just look, you took it in, you saw it accurately, you saw it. And in love, well, I think that the feeling, the swoon, the pitter-patter is like look, and you're easy for someone to say oh, Abigail, you know, won't you go in my chariot with me, whatever, won't you come up to my room tonight, whatever. But to love you effectively, which is the achievement verb, you have to frankly rise to a certain level. And I think the best compliment I ever got who was this one of your, maybe someone who you dated or something in the past who said this was like Jerry's great achievement. Do you know what I'm trying to refer to? Yes,. And I remember that's the best compliment I've ever received, that somehow I succeeded. He could tell from the way you talked, I guess, that I succeeded in actually loving you, not just, you know, feeling I was in love.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal: Yeah, that's very interesting.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 22:22: It’s about the ontological layer, that layer of being itself, reality itself, just the opposite of what all the wiseacres tell you. They tell you it's an illusion, a delusion. You'll get over it. It's a moment of madness, it's chemistry that you know, you'll shake up the, the chemical elements and you'll be out of love the same way you fell in because again somebody shook the container, but no. You know the end of each book of Dante's divine comedy, I think, if I recall, rightly, ends with a reference to the love that moves the sun and the other stars. And of course, in Dante's 13th century day, he was referencing the physics of the day and the astronomy of the day, the Ptolemaic world system, but, and so we are all taught in the history of philosophy, or the history of science or wherever we're taught about what's happened in the culture over the centuries, we are taught we are no longer Aristotelians or Ptolemaic thinkers, and modernity has push and pull, but it doesn't have any room in it for what they call the secondary qualities, like color and sound and love. You know, in other words, the actual world we live in.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 24:25: But you know, I don't know when physics will ramp up and go through another shake-up and maybe come out closer to the world of Dante, but I do remember and this is not just about romantic connection between you and me, darling, when my father was dying, I didn't want to let go of my father, and I put a hand on where I believed his heart was. I'm not that great with anatomy, but it felt as if that’s where his heart was, and so I seemed to have a very profound connection in that moment, and what I felt was that my father, who was also a philosopher, was communicating something to me silently. He was in a deep coma, so he was certainly not telling me anything consciously, but the matter, the thought that was running from his heart up my arm was that love is what actually makes the planets go round, what actually moves the sun and the other stars, what actually in physical nature, just as Dante believed, moves the subatomic particles around and the things of a larger dimension in the universe around, moves the sun and the other stars. That's not poetry, that's reality.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 26:25: And you know, I don't know when the physicists will climb up the ladder back to what Dante knew, but I expect if they keep working they will. They already see some kind of correlation between the viewer of subatomic particles and the particles. There's some sort of interaction or knowing, or connection, or sympathy. And you know, keep going, fellas, I'm sure you'll get there, and more power to you when you do. But meanwhile we live in a world that moderns define in terms of cold, insentient ultimacies. Ultimate particles have no feeling for each other or for themselves, and I think that's probably a wrong view in physics and in metaphysics and in human reality.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 27:32: Yeah, I was reading a writer saying you know, an egg is an egg and it's only pre-moderns who can say that. Since the 16th century we haven't believed that eggs are eggs. We think, like Hume, that it's a stream of impressions, you know, organized like Comte, that, no, you can't see the egg at all. It's often the thing in itself or something. You don't know what an egg is. Descartes is just the secondary qualities. The egg, no, it's not a white round thing and so forth. It's not something you crack open and make an egg, you know, cook up for a meal. All of that's sort of unreal, the only real part are the quantitative aspects, and they are far from the reality of an egg. And speaking of that love element, the older view of teleology that you understand things best by their function, by what they are tending toward, well, what is an egg tending toward? Well, it's going to be if we don't crack it open and eat it, which is a violent act. Aristotle would have said that cuts across its nature. What is its nature? Its nature is to become a little chick and then be a chick, and then a big chick and then a mama chick. You know, lay more eggs and so forth, and the language of desire is not quite inappropriate there. You know, the seeds, desire to become a tree and so forth, and that's, you might say it's metaphor or whatever, but it's a pretty valid concept. And you ask what is an eye? I've never seen any definition that is going to be better than well, an eye is what you see with. That's its function, right? What is the eye trying to do? It's trying to see things and it's trying to see them so much that it actually delights in seeing them. You know, the eye enjoys, we don't just use eyes for practical purposes, seeing things for practical purposes, we do them for enjoyment and even for seeing the depths of one another. You know, we encounter one another visually and tactilely and so on, and that's a real person and a real reality.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 29:56: Yeah, you know. Yeah, what is pleasure? Aristotle says it's the bloom on the rose, it's the sort of a foam on the experience. It's the confirmation that this experience really is happening and really works, and we deeply enjoy that. You know it occurs to me as you and I are talking now, that after all, we are by profession and vocation philosophers, and that equipped us not to buy unexamined the common sense of our particular era. We know that common sense changes. It rests on the top, the surface of worldviews, and worldviews change scientifically with the history of the exploration of nature, sometimes philosophically with the reflection on not only the sciences but other noteworthy, important features of human experience, historical experience, sometimes shocking events that upend expectations and cause people to go back to the drawing board and say we didn't expect this, but what should we make of this? So we know from the history of philosophy that what is called common sense is not self-evident truth. It's not the igneous rock of the planet. It changes, it itself is contingent and dependent on certain assumptions which have been in the past and will be in the future, challenged. So we are not at the mercy of fashionable opinion, we just know enough about the history of fashionable opinion to know that that's not bedrock, that's surface.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 32:27: Yeah, those things change all the time. I was thinking also of literature, art, the romantic writers Byron and Keats and all these people shake the mentality of a whole period and became the common sense, the common currency of that period where its all feelings and so forth. And feelings probe reality in the deepest way or the highest way. Later you have things like theater of the absurd and paintings like Dali and so forth, drippy watches from the trees. I don't know what Dali is about, but it's certainly unsettling and somehow looks like a rather incoherent picture of the world. There are things that turn belief upside down and inside out. I don't know what the meaning of Waiting for Godot is, but Godot never shows up and so you know it looks like an exercise in futility. Or Sisyphus said by in Camus' version be rolling that stone up and down, up and down, up and down, and it just rolls down every single time. Okay, that's a metaphor for life.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 33:43: Yeah, and these fashions in contemporary opinion rest on either philosophical arguments or experience of one kind or another. It might be that World War I shook up by its horror trench warfare, poison gas, the expectation of progress which had animated and made optimistic the 19th century. And I remember Henry James writing, I think, to Edith Wharton about World War I: Was this where we were tending? We have lived too long. So sometimes a shared big scale event upends assumptions that have governed the culture, sometimes an actual change in philosophical work, Kant changed the Newtonian assumptions of the eighteenth-century writing to demonstrate that they governed our rational aspect but did not govern our intuitive and extra rational aspect. And so a philosophical treatise, the Critique of Pure Reason, opened the door to romanticism. Byron, Keats and Shelley and all those guys, whole sensibility, read Kant or read about him and decided oh then, we can touch reality, just not with our intellects, we can touch it with the depth of feeling and sensibility. And so a whole cultural change took place. These take place, students of the history of philosophy, students of philosophy who've lived any length of time, have seen some of these changes occur. And we know it's not sacred just because everybody believes it. Everybody thinks so. Well, good for that person who thinks so. But meanwhile the truth might lie elsewhere and has its own course of development. And you and I both, I guess, being open-minded, non-dogmatic knew that it was quite true, that we loved each other, and that was truer and rested on a deeper foundation than the conventional belief that that was impossible, that we were simply victims of a kind of delusion. No, we weren't. We were observers and livers through of a depth, of an experience, of the depth of life, and we knew it.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 37:12: And that's why I prayed for the first time, not having any beliefs. But much as you were talking about Tristan and so forth, something comes piercing through the surface of life. You know, the common sense, the facticity of life, the simple everything is what you see. You know, and something pierces that, that there are further dimensions, and to me, it just seemed, I had not reflected on all this as much as we're doing now, but I just thought this is like a miracle. I didn't do anything to bring this about. Where does love come from? I don't think it's DNA. Some people would say that, I heard somebody talking, it's all just chemistry. Well, he thinks everything's chemistry. Your duty to tell the truth is just chemistry. You reduce everything and then somebody else will come along and say, yeah, here are the chemicals in the human body and they're worth $97.50 in dollars and cents. This is what you cash for. Well, that's really inadequate. At least, it doesn't account. It simply fails as an explanation of actual love.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 38:25: And so I didn't have these, at that point, ontological reflections that came up as I went on. But I thought, you know, there's something more here. And anyway, it's like a miracle to me because I didn't make this happen and here it is, and so thank you, lord. Whoever the Lord is, maybe a benign universe? I didn't worry about doctrinal issues. I just was expressing, I guess, a natural reaction to reality as I had just encountered it in falling in love, and I thought you know, you don't have to have a big theory. You're talking about, you know, saying what you mean and so forth.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 39:11: Being truthful, what I knew was that this expression of thanks to God, whomever was sincere, I believed it. It's how I felt, and I didn't think to express an authentic feeling required having a theory of that feeling. You know, some birther set of propositions or something about it. No, here it was, I was grateful for it. It seemed amazing, it seemed miraculous, but again, without any theory of miracles or laws of nature or any of that stuff which doesn't seem to get you very far in any. But here it was, here it was, and I responded.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 40:02: You say grateful. That stands out to me. A lot of people would have said you know, gee whiz, that's amazing. People look at the Grand Canyon, I guess I haven't seen it, and they say wow. They don't necessarily say I'm grateful for the Grand Canyon. I guess I haven't seen it, they don't necessarily say I'm grateful for the Grand Canyon. To whom would the gratitude be offered? Why did that word come to mind?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 40:35: It is funny because I think it's a very fundamentally sound attitude. You know, if you look at the things a healthy mind, a healthy person needs, one of them is gratitude. What does gratitude mean? I don't know. It starts with not taking things for granted. A lot of couples, happily married for years, fall in to unlove by taking each other for granted, whereas I told a woman helping us, you know, your husband should fall at your knees in gratitude. You know it's a wonderful woman, he's very lucky to have her. And does he know that? Most men don't very well, take that in, but he should know it. And that's why people pay attention. Say, you should have a date night, you know periodically. And you know, cherish this, continue the romance. The romance should not die and I guess that's part of the gratitude is….

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 41:39: I mean, I started thinking about miracles, you know, because of this sense and I thought it almost goes back to Aristotle saying what is it, philosophy begins in wonder and you know, lots of things are amazing. We take them for granted that human beings are alive, that there's a life. We're looking for life somewhere in the universe and it seems hard to find. Why? That's kind of puzzling. We now have the ability to detect planets and galaxies and so forth very far from Earth. And yet right here we have life, and not just life like moss, you know, or something, but fully developed intelligent life. Wow, that's amazing. And we have dogs. They're wonderful too, because they love you. No matter as long as you feed them, they love you, and that's wonderful. And thinking about it further, that we're conscious is wonderful. You know, we could just be beings like robots. The rocks, apparently, are not conscious. One never quite knows where the limits of that receptivity to the world is, but we certainly are conscious. Well, what a blessing that is. Think how much more interesting life is because of that. And even you know, look at the fact of love you could easily reproduce the species, those salmon. Without love, the salmon, as far as I know, simply feel an internal imperative to go, swim up that rough river, through rapids all the way up to plant their eggs in some place they're supposed to plant them. Then eventually, those eggs hatch and those salmon, or whatever fish it is, come down the river and into the sea and then later do the same thing again themselves. Well, you could just have people like that.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 43:40: Why is affection, tenderness, you know the subtleties of relation of person to person, in love and romance and even daily life, being appreciative of one another. That was a nice thing to say. Or you look good. You know, we have a good friend whose husband, dying at that point from leukemia, one day just looked up and said your hair looks nice. Well, that's a nice moment, isn't it? And we have those capacities, and so it's all a miracle all the way down to why is there something rather than nothing? It would have been simpler for there to be nothing. So why is there something? And you don't know quite how to answer that sort of why question. It's sort of too basic or something. And yet it is kind of amazing that there's something rather than nothing.

Scott Langdon 44:46: Thank you for listening to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. Subscribe for free today wherever you listen to your podcasts and hear a new episode every week. You can hear the complete dramatic adaptation of God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin by beginning with episode one of our podcast and listening through its conclusion with Episode 44. You can read the original true story in the book from which this podcast is adapted, God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher, available now at amazon.com, and always at godanautobiography.com. Pick up your own copy today. If you have any questions about this or any other episode, please email us at questions@godanautobiography.com, and experience the world from God's perspective as it was told to a philosopher. This is Scott Langdon. I'll see you next time.