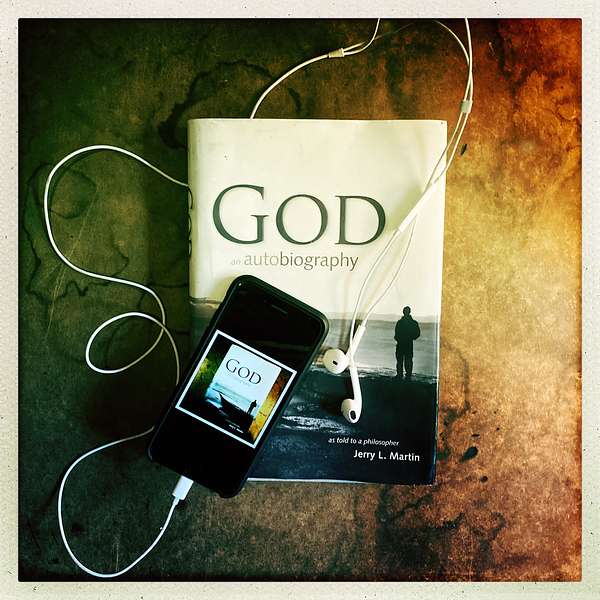

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

241. Jerry & Abigail: An Intimate Dialogue- What We Learn Through Love and Suffering

What does it mean to love someone deeply in a world where suffering is inevitable? Jerry and Abigail return for another honest and intimate reflection on a recent health crisis that brought the pair face-to-face with mortality, vulnerability, and the aching intensity of love throughout it all.

After Abigail suffers a near-fatal injury and a cascade of medical complications, Jerry and Abigail recount the physical ordeal and emotional aftermath. The couple invites listeners into the raw and tender space of survival, caregiving, and spiritual insight while wrestling with questions like: Why does suffering exist? How do we stay open when life threatens to shut us down? And where is God when we feel most broken?

Abigail shares how her sense of self narrowed in response to pain, leaving her with the most minimal form of consciousness she had ever known. Jerry reflects on the surprising joy of enacting love through caregiving. Together, they explore the spiritual transformation that can arise from shared adversity and how moments of crisis can reopen the "skylight" to grace, love, and the transcendent.

From Shakespeare to William James, trapeze metaphors to real-life hospital corridors, this conversation weaves together philosophy, storytelling, and spiritual wisdom as the two (deeply in love) philosophers provide this reflection on suffering as a guide to loving through it, learning from it, and finding God at its heart.

Are you walking through hardship or supporting someone who is? Tune in to hope, grounding, and an invitation to stay spiritually open, even when it hurts.

Related Episodes: When Suffering Strikes

Other Series:

The podcast began with the Dramatic Adaptation of the book and now has several series:

The Life Wisdom Project – Spiritual insights on living a wiser, more meaningful life.

From God to Jerry to You – Divine messages and breakthroughs for seekers.

Two Philosophers Wrestle With God – A dialogue on God, truth, and reason.

Jerry & Abigail: An Intimate Dialogue – Love, faith, and divine presence in partnership.

What’s Your Spiritual Story – Real stories of people changed by encounters with God.

What’s On Our Mind – Reflections from Jerry and Scott on recent episodes.

What’s On Your Mind – Listener questions, divine answers, and open dialogue.

Stay Connected

- Share your story: questions@godandautobiography.com

- Get the book

Share Your Story | Site | Facebook | Instagram | Twitter | YouTube

Scott Langdon 00:17: This is God: An Autobiography, The Podcast, a dramatic adaptation and continuing discussion of the book God: An Autobiography as Told to a Philosopher by Jerry L Martin. He was a lifelong agnostic, but one day he had an occasion to pray. To his vast surprise, God answered in words. Being a philosopher, he had a lot of questions and God had a lot to tell him. Episode 241

Scott Langdon 01:12: Welcome to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. I'm Scott Langdon. “The challenges we have in life are not matters of high theory. They're situational, so close you can touch them with your hands.” These are the words with which Jerry began last week's episode and latest edition of From God To Jerry To You. He followed by explaining some of the details of recent weeks in which Abigail has suffered greatly because of a sudden fall and other health issues that followed. I'm very grateful to say Abigail has recovered enough to join Jerry for this week's edition of Jerry and Abigail: An Intimate Dialogue, and in this episode the couple dive more deeply into their experience of finding God in the midst of suffering and in the search for meaning in it. Here now is Jerry to get things started. I hope you enjoy the episode.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 02:07: Well, thank you, sweetheart, for joining me in another intimate dialogue, as we call it, and I think we've had a hard time and we're going to reflect on it. We had an event May 2nd and I'll ask you to say something about that in a minute that has repercussions bad for you and me, and other exogenous events intervening that were almost as bad as the original, maybe worse than the original event, and this is still unfolding. We're in the middle of it right now.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 02:51: And, praying beforehand, my guidance was to go into the heart of suffering. It's hard to know exactly what that means, but maybe just start there. And you know we're talking about our own suffering. But I assume listeners who may or may not be interested in what Jerry and Abigail are going through, are going through their own challenges, right, their own suffering. Everyone encounters these things, if not today, then tomorrow or in the future, and it's important. One of the mysteries of the world is why all this horrible suffering? But anyway, here's our case study, you might say our particular example or instance of suffering, and it starts, oddly enough, when we're invited to speak at Princeton Theological Seminary. And minutes before the panel is to begin, you step off what looks like flat ground but is in fact a step down into hard concrete and whammo, there goes the hip, the leg. You're put out of commission.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 04:22: Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 04:23: Yeah, and they race you off to Princeton Penn facility. A surgeon does his thing and I guess it's a big thing because you're going to see the scar runs way down, because it's not just like a little hip module as I had first envisioned such a thing, but there's a whole broken bone and the whole thing has to be opened up and some metal or silicon or whatever device put in.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 04:54: Titanium.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 04:56: Titanium. That sounds really super duper. You know that you're going to be able to run up mountains with titanium, but no, it doesn't quite work that way. It just slowly heals as a usable piece of equipment of your bodily equipment and I don't know if you want to say something about that, sweetheart. I mean, the suffering of that is obvious, the pain, the ordeal, the hospitalization. But there was a whole second event.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 05:32: Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 05:33: Where, if we had not at the last minute, you might say call 911 because we'd gotten some medical advice that put us in the wrong direction, but your blood pressure suddenly dropped to 60 over 40, which is the lowest blood pressure I have ever heard of and we called 911. And had we not made that and they came instantly you would be dead now. We wouldn't be able to have this discussion and, as it felt to me, my life would have been over. You know, in meaningful terms, but yours would have been over on this planet in literal terms. And that was another ordeal leading to procedure.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 06:18: They had to put in three pints of blood and you have every day, this is how the unfolding goes on. You have physical therapy at home, three different people who are coming around each week and making you do all kinds of strenuous things that your body was not up to doing. And yet here you press it as much as you can and with never a day off, because, as you and I were saying this morning, you can't take a day off because then you slide back, so you've got to keep pushing, pushing, pushing, and if you go into the heart of that suffering sweetheart, what do you find there?

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 07:06: Well, it was odd, the whole experience, especially at first, the repairing of the hip fracture, partial fracture. What I did was contract, mentally, retract so that I would coincide with the event. I didn't decide to do this. This wasn't Zen and the art of hip fracture seemed to have automatically pulled in so that I had no intentionality larger than my body's being, as a kind of thing. I just stayed inside of it and maintained probably the most impoverished inner life I've had since I ever had inner life. I had no life additional to being conscious of the life that accompanies consciousness of one's body. I should imagine that an animal's inner life is the consciousness of its body, and that's how mine went. And I didn't know or particularly strive in to transcend the fact that this might be the end of my life. Had practically zero transcendence.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 09:04: You know, the um, consciousness of one's consciousness was wholly minimal. There came a second point, farther down the road of this experience, where, you know, I could feel my body from feet up the legs, up the middle section, up the chest, marching toward the head or heart, suddenly very cold, trembling, and I knew that this was danger. And I think I said, together with whoever you and the nice person who was happening to be there, this we need to call 9-1-1, this is, uh, beyond what my body can recover from. It's not a normal reaction to something where you bounce back.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 10:30: It rather sounded like death moving up your body yeah, the most vital organ to the final conquest over life it sounded like with your shivers and everything.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 10:46: Yeah, it was intolerably dangerous.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 10:49: Yeah.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 10:50: And I knew that nice crew from the ambulance was good for a situation like this.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 10:58: Yeah.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 10:59: As long-distance medical advisors were absolutely not. All they knew was what they wanted to know, not what was fact. The ambulance crew deals with facts and you know it's sort of like calling in somebody to rescue you when you're drowning. They don't have a theory, they need to get the water out of your lungs and get you out of the pool or the ocean.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 11:33: So the ambulance crew was really what stood between me and death in death and in the course of going to whatever kind of urgent care in the hospital was mandated where several times at least twice, there had to be an operation to repair what the medical you know if I were in the law business malpractice or mistakes for which no one took responsibility, which is tragic because it tells me and I know this from a friend who lost her father to this kind of miscommunication he died because it wasn't told to the people on scene what medication he absolutely needed. Anyway, several interventions to repair the tears in my body that had been the consequence of these miscommunications. At a somewhat down the road point from that I had a sense of the happiness that's part of my life with you, Jerry. That ordinary life screens me from level reaction, and deep level reactions comport vulnerability and for the purposes of ordinary life I had clicked out that degree of self-sensibility.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 14:04: Explain that a little more. What was the self-sensibility that was pushed out?

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 14:13: When we first fell in love, it ushered me into a larger space than I had inhabited as a person who was not in love. It opened up a kind of skylight that had closed off a piece of sky, and when we first fell in love, I went up past the skylight and was intensely happier and intensely aware of the vulnerability of that. And so, once I adjusted to this new condition and it made it obvious that we need to remake our lives, that it wasn't sufficient to commute, that it wasn't sufficient to commute, it wasn't sufficient to be apart, you were living in New York.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 15:29: We both had full-time jobs, you in New York, me in Washington DC. A lot of people have these little commuting…

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 15:34: Yeah, and I was advised by my academic colleagues to do that, to have a commuting marriage so that I wouldn't be giving up life in Manhattan and a good job and, you know, very desirable circumstances. But the falling in trajectory had an absoluteness to it that precluded those kinds of convenient compromises, with the absoluteness of love and of course you don't give up a job people would kill for and an apartment people would kill for. But it seemed as if and a demandingness about the experience we had. It ushered me into a new frame of mind, a new frame around the life that the two of us would have, different from what you acknowledge, in a commuting marriage where the framework remains what it was before.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 17:09: The whole experience was somewhat overwhelming for each of us in our different ways, but we shared that with each other, that it was as though we didn't have enough, I think we used the word conduits or something in our bodies to absorb this phenomenon, and so that overwhelming feature has been in the, I suppose, been in the background ever since. It's rather a dominant feature of the Gestalt of our lives, since that time on.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 17:53: And you know what happened to you subsequently, or me, in terms of our work lives was a kind of flowering, tremendous expansion. You had your God experience once these ceilings were opened up.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 18:05: Exactly.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 18:07: Yeah, it was. You know the exact cause and effect, the exact sequence that led thither you've described both in your God: An Autobiography book and in the more recent book, Radically Personal, in my case my book a Good Look at Evil gained two more chapters and a new edition, and both of those additional chapters, with a new publisher involved, would not have been possible if that skylight hadn't opened. There was simply a new birth of insights, or a new admission of insights into my reality. That was possible with the skylight open and not possible prior to that. Likewise, the drive to publish Confessions of a Young Philosopher, which had had a prior edition, but this time to publish it adequately, to illustrate it, to get it illustrated, to get it in the right frame, all were shakeouts from the new space and time around us.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 20:47: How did these medical events the breaking of a leg and a hip and it turns out you were losing all this blood and it's got a big hole in your stomach, what they call a bleeding ulcer, but it's a big hole that they had to kind of cauterize and sort of try to close and the first effort only succeeded halfway. They had to go back and do it again. I mean, they kept having to add blood to you, otherwise, you know, you would have expired. It takes a lot of blood to keep bodies going and fortunately they can do that, add blood. But how did all of those events intersect with the story you're just telling about this tremendous impact that our falling in love had on us as personalities, on our thinking, our life horizons?

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 21:47: What I know and I'm not sure I know all there is to know about this, not at all sure. What I know, what I believe I learned, was that I had been repositioning the skylight to some degree so that I would live quote normally, you know, not in the presence of this ecstatic grace and this, which comported vulnerability, as I assessed it, you know, rather unconsciously, I didn't decide let's shutter this experience. That would have been stupid. I’m not consciously stupid, I'm unconsciously stupid, so unconsciously I shuttered, I closed to some degree this skylight so as to live more normally, as I thought, and probably lived with less openness to the transcendent for daily purposes, without being conscious of having made such an unconscious decision. In the crisis of not near death in the sense now being popularized, where people go to the other world and meet their departed loved ones, but near, empirical death. Near, you know, the body dies and consciousness goes wherever it can after that, you know, that kind of death, I couldn't be screened from ultimate things, and so one of the features of the experience that was that I became once again conscious of the sort of open skylight happiness of being with the guy I love most in the world. You know the drama of that, the excitement of that, the quickening of that, the consolation and comfort of that, something that I hadn't wanted to deal with the risk of that one or the other of us can die and leave the other one, and it seems too risky.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 24:59: The classic medieval tales of the coup de foudre, the stroke of lightning, the lovers don't last, they die. Romeo and Juliet die, Tristan and Iseult die, and Dante and Beatrice, when he finally meets her in his vision, she reproaches him for not being dead yet so that they can be together in a proper manner. So there is something in the literary acknowledgement which seems medieval, since all the examples I'm talking about are ways I'm medieval or a little bit after medieval, the world doesn't hold that. The lovers are set to die, and you know, we're Americans, we don't want to die.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 26:18: We're not trying to ascend, we're trying to live in a practical manner, be more normal and cope with life. And, there's something, it's as if I remember many, many years ago on the Rue de Tournon there was a cafe a little downbeat from the Tournon which was more upscale, Chez Maurice, and there were some Russians talking there and my friend Marie understood their Russian talk and I said to Marie what are they saying? And she said you really want to know? I went, yeah, what are they saying? They're speaking so soulfully. And it seems one was saying, “What is love?” And maybe he answered his own question. He answered. “To love is to suffer,” and I thought, well, yeah, I don't know if to love is to suffer. To love is to undergo, which, in the technical sense, is to suffer love. What frightened me was to love is to open the soul and therefore to open it to a wider expanse of suffering. The opened soul. We speak of open soul. That maybe, William James, you know more about that than I do right now, but the opened up soul is opened up to what we most fear, which is suffering loss.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 28:29: One would think from what you just said, sweetheart, that this trauma of the events you've been through near death, including near death, would make you pull back more. I mean, that would bring right up front the vulnerability of suffering. I know I've told friends that before I found my true love I knew how to live life. I was doing fine. You might say it was kind of black and white rather than technicolor, but that's fine. You know you're making my way and I was aware immediately I now have a new vulnerability.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 29:09: It would now be very hard, just once you get color TV, it's hard to go back to the black and white. It'd be very hard for me to go back. In fact it would be harder than that little analogy I produced, because it would be as if all the color from life, all the meaning, was just drained, would just be drained. And I just knew that's now a possibility. And you would think from what you were just saying, sweetheart, that given how it was overwhelming and you're already halfway shuttered, the skylights because this is too much sun and too much vulnerability is what that meant, but now with the increased dangerous events, the dramatic sharply painful events make you want to close it off entirely and just kind of withdraw. But it did not have that effect.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 30:12: No, I'm not that stupid. I'm a philosopher, I love wisdom, so I understood.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 30:20: I'm learning something. This is the teaching very unwelcome. The whole, you know, the whole schmear, the whole broken windows of my life, the whole jaggedness of it, the whole, as the French used to say, or whoever says that, absurd, l'absurde, c'est l'absurde, oh God, the apparent meaninglessness of it. Who trips on a veranda and breaks bones, and you know who dies from medical mismanagement of one's case? Talk about how you might want to die, firing squad, some dictatorship says swear allegiance to the dictator and you say give me liberty or give me death. And they say rat, tat, tat, we have death for you and that's meaningful.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 31:30: But to die meaninglessly because of these idiot, unprofessional, unloving, uncaring people who are punching out their present from nine to five cards and not thinking hey, there's a human being, there's a brother in need, there's a soul that depends on you, buster, and shouldn't depend on you because you're not good for it. So that's why I'm supposed to die? So the whole thing absurd in the worst way, trivially absurd, accidentally absurd is bringing me up against life at an end and so I can't get around. You know, whatever is ending or whatever is threatened, I can't afford a two-tiered life. The whole mess of my life comes into play.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 32:49: This is what is being absurdly threatened, you know. This is what is under the gun of medical idiocy, medical irresponsibility, and, as I sometimes say, as stupid as I look, not being stupid, I see. Oh, what was being threatened with an absurd, unhappy, accidental ending is intensely valuable, you know, is happiness itself. It's not that you and I are daily ecstatic on a normal day or on these abnormal days, it's not that. It's that we're open, wide enough to be fully with each other, with our lives, with ourselves, with what comes from above, with what you know nags from below or from one side or the other. But we're much more open, we're much more present. Love is permission to live as fully here. That's the permission and I don't know about that Russian guy: to love is to suffer, but in the technical sense of to admit, to undergo. You know he's right. To love is to suffer, to suffer love.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 34:55: Yeah, you know a lot of my experience other than the intense, the yikes, feeling that my wife is mortal after all. You know, and one knows it. But I felt ever since we hit our 80s and are still hyperactive professionally. I can barely believe it, but I felt a bit as if we were like the cartoon characters who run off the edge of the cliff and they keep going, you know, until they look down and then yikes, then they fall to the ground and so I feel as if I've been going along not looking down, and an event like this forces one to look down and there may be some wisdom in not living the peddling of the air life, you know, trying to sort of levitate. But you know, and you often say we need to get our wills in order and we already have a tombstone. So, you know, one has to pay attention, of course, also to the medical details of life and one's exercise and what one's eating, and you know all of these things and get the bills paid and those are all fine. They're in a way the trivia of life, except they're the trivia of life that sustains everything one most cares about in life. And the other main experience I had, sweetheart, was the joy of helping you. You go through this together. I admired how you handled everything. So it was an exhibition, you might say, in a lot of the virtues of Abigail your persistence, you're taking the PT so seriously, you're doing everything they tell you, even from the beginning, your inner vitality.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 36:54: David, my son, was up here helping us and he remarked, found it just remarkable that you okay, what are we going to do next? Okay, and your lack of I don't know, oh, poor me, which I think would be very prominent if it had happened to me. My reaction, but you do not have. You certainly let people know, yikes, I don't like this, but you don't have that kind of I don't know victimhood mentality or something. But also, I just got to be of concrete help in all these different ways. And people, when they share, even share the stories of their suffering with friends, they think I shouldn't burden you with this. But that is not a burden. That enables friends to be friends, that enables lovers to be lovers and this is one's chance to enact the love.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 37:49: Love isn't just a pitter-patter. I'm always saying this. Love is an action verb. You know, you love somebody, you want to enact it, and then you enact it in a whole life, of course, but you also enact it in these concrete ways, in part by date nights and Valentine's dinner and so forth, but also just concretely and managing the challenges of life, and certainly in a medical crisis, which this was.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 38:18: It gives me, as your lover, the chance to enact that love in very concrete, you might say life-sustaining ways, because you need that kind of help when you're in trouble, and this enables, gives me the opportunity to give it, and I think that would apply to a lesser degree, of course, to friends as well, friends and neighbors. You know, if the neighbor needs me to bring them soup because they're sick, well, that lets me do something helpful to someone and that's an opportunity. It's a little bit of a burden, but it's also a very nice opportunity. So, anyway, to relate, people connect, people need relationships, and relationships is not all high love, that's one and kind of an ultimate sort of relationship to find your true love and fall in love. But there are these other wonderful connections. We have people who help us in wonderful ways and which we very much appreciate.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 39:46:While you were talking, an odd thought came into my mind, marched randomly into my mind. I was thinking at the end of the play Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet, somebody I forget who says, “Never was story of more woe than this of Juliet and her Romeo.” Accidentally, they're feigning, she feigns death in order to be secreted away from those who keep her from her true love. He thinks she's dead and so he actually kills himself and then she kills herself. I hope I've got that.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 40:38: That sounds right and she kind of comes out of it and then sees, oh my gosh, he's killed himself. And then she does it.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 40:44: Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 40:45: It is a tragic tale of woe.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 40:48: It's pretty woeful. But for the first time it occurred to me, as you were describing the consolations of helping me that were visiting you, that it was consoling to you to be able to do that. I thought of this, you know fabled pair, and for the first time I thought oh, what's sad is not just that they died while they were young and pretty, but they couldn't help each other.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 41:35: They really had to deal with the family conflict you know each one to explain to the other the unreconciled clan which hated anybody from the rival clan, that they loved each other, they would either be disowned and have to find some kind of a terrible job to survive or they might, over time, effect a reconciliation, or a fractional version of both, and they lost the opportunity to live through life's fractional peniles that are not storybook but are organic, the politics of experience, that's what belongs to a couple. And they were robbed of the politics of their love, which is something that had to be, that demanded efforts at resolution. Dante and Beatrice didn't live the politics of their love, whatever that would have involved. The church didn't allow divorce. They were both married, Eloise and Abelard. Well, they did live the politics of their love and it was tragic, but they lived it through and they still loved. So they are an exception to this cast of characters.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 43:44: Sometimes people live that badly or in the mode of betrayal, where, as I think, Arendt and Heidegger lived the politics of their love badly and in her case, in the mode of betrayal. I've argued that. So what you were reminding me of was that the hardships, the chores, the burden on you, as we are not spring chickens, the physical burden, the psychological burden, the fact that you have other enterprises with deadlines on them and I have a weekly column, at the very minimum and a book to publicize at the max right now and other projects to go forward with all all those demands of life which we were carrying together with the demand of my injuries.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 45:16: There's something you know kind of the kiss of reality, in that it's a vindication. It's oh, we could do this too. Well, that ain't bad.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 45:27: Well, I'm going to remind you of something. Before any of these events, long before, when I had just met you in person, I fell in love with you on the phone. That story is told in God: An Autobiography. But we then did get to meet in New York. I went up, we had dinner and so forth. We went to the Metropolitan Museum, I guess, and had lunch.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 45:53: The previous week I'd come up and you had told me about your life. On this occasion you were asking about my life. I shared with you the great, defining, difficult moment of my life was the death of my brother. That was a defining moment. He was an infant. I was about four years old. I don't know how old he was, but they were measuring it in weeks. He was X weeks old, you know, and an infant. And I won't tell the story now. But the outcome of the events was of the death was that my mother was in such grief and it went on and on, year after year that I was emotionally on my own, I was abandoned, and this caused distress that nobody recognized but it manifested in behavior. And finally, when I was in fifth grade, she found out the source of this stress and got it somewhat corrected. But anyway, when I told you that story and how it affected me so badly, what you asked was and I thought this was so remarkable, my mind would never would have gone to this question. You ask what did you learn from that experience that you wouldn't have learned any other way? And I won't probe that. That's a story we might talk about sometime, but I think it's a good question to put to any of these kinds of experiences.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 47:31: You go through a hip fracture and that ordeal. You go through blood loss and near-death moment, in that case I go through my first thing, oh my gosh, we are vulnerable. After all, we're going to have to look down. Yikes, there's the ground coming up fast.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 47:48: And yet I do notice chances to help and to enact love, to make it not just an oozy feeling but to do it, to do it and to be a true love to you, and notice traits in you that I came to appreciate more, like looking at the diamond. You know, under facets of light, sides of light, you look at the diamond shows in different ways and you look up close through one of those eye things and it was like that. I had that opportunity to look up close again at certain facets of you that are so admirable and beautiful. But anyway, that's a good question, I think, for all of these moments of suffering is well, what did you learn from it? Because these are also moments of learning, moments of potential insight, moments of grounding in certain aspects of reality that maybe weren't being grounded in so well before.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 48:55: Well, I sort of feel like I'm going out on a limb, speaking of cliffs and the limbs in the answer that comes to mind. But, I feel that in a way, it scares me to say this, I feel more in a God-dependent relation to my life. When you’re a kid, playing in central park, there's a kind of metal thing to play on where you swing from one level to the next. And it's hard to do because to swing from one set of parallel bars to the next you have to let go and that's scary, and I guess trapeze artists are big on that.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 50:22: The key to trapeze artists. I was surprised when I learned this. You know they swing and one swings and is thrown in the air and another catches her. It's often the woman being swung in the air and two guys at each end and the guy catches her. She does not grab him at all, she just floats. And the person I was reading this in was saying that's how you need to relate to God, where you're not grabbing God's hands, as it were, but you're just doing your best, floating through life as best you can. I'm sure there's the art to just being thrown in the air and so, okay, we've got to have that art of being thrown in life, but then let God catch us. However, God catches us.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 51:16: Yeah, that's a very good image of this, transformation, if that's not too large a word or too heavy handed a word, almost sounds clinical or theological or some kind of logos of something. And I, you know, as if there's a doctrine of what I'm talking about. But it's not a doctrine. I had more doctrines before, when I was less theistic, less God-oriented than I am now. I had, you know, more bars to swing from.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 52:08: But it feels as if one of the questions that people mask from themselves and the masking gets more strenuous as you get to a certain age is what do we do if and what do we do when? And it felt, it seems to me, that that question is more infused with the question's answer, which is God and us can work it out. We can work it out with God's help. You know it's more, maybe there's a team player feeling about this more. There are people who long for God, who hope for a mystical experience, who pine for miracles or visitations when they come. I don't know that, beyond adolescence, when I read about mysticism and great saints and stuff, this characterized me. I tend to take it as it comes my phases of atheism, my phases of God connection, my deeper or deepened God connection, I just feel it’s like a relationship whose permanence you trust, even when there are phases of estrangement. So in this case I'm not writing some theology about this, but there has been a shift in the balance wheel of my life, and the shift has suggested to me, has induced me to feel less covert panic about the last crises, if and as they inevitably come, maybe not so panicky. Maybe that too involves a partnership, a sense of God not being absent.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 55:12: Yeah, I was thinking of what God told me before we had this discussion: go into the heart of suffering, and I thought that was an interesting way God put it to me to go into the heart of suffering, and probably at the heart of suffering, that's where God is. Well, sweetheart, I've, as always, enjoyed talking to you and appreciate your joining me.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 55:47: Appreciate your inviting me to join yeah.

Scott Langdon 55:55: Thank you for listening to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. Subscribe for free today wherever you listen to your podcasts and hear a new episode every week. You can hear the complete dramatic adaptation of God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin by beginning with episode one of our podcast and listening through its conclusion with Episode 44. You can read the original true story in the book from which this podcast is adapted, God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher, available now at amazon.com, and always at godanautobiography.com. Pick up your own copy today. If you have any questions about this or any other episode, please email us at questions@godanautobiography.com, and experience the world from God's perspective as it was told to a philosopher. This is Scott Langdon. I'll see you next time.