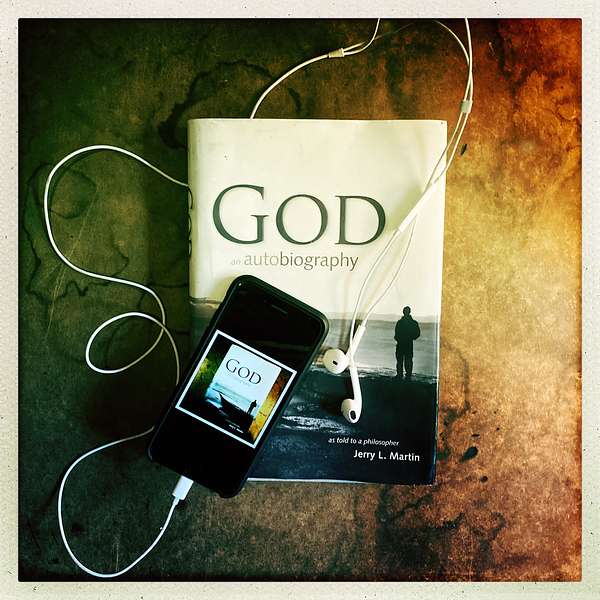

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

253. Jerry & Abigail: An Intimate Dialogue: Romantic Love and Divine Revelation: When Trust Becomes a Spiritual Calling

When can love—and even pain—become a form of revelation?

In this powerful dialogue, Dr. Jerry L. Martin and Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal trace the mysterious link between romantic love, moral conscience, and divine communication. Abigail shares two defining experiences of spiritual discernment: a moral act that cost her a lifelong family bond, and the unexpected moment she realized she was falling in love. Both called for the same inner movement—trusting what had her name on it.

Jerry reflects on his own “Why me?” experience of revelation, exploring how trust bridges the human and divine, and how moral courage and love alike can summon the soul toward its destiny. Together, they ask: How do we recognize the voice of God when it speaks through ordinary life? When is trust not blind, but a sacred form of clarity?

Drawing on philosophy and lived experience—from Aristotle and Husserl to the dream world of conscience—Jerry and Abigail reveal that divine communication doesn’t always arrive in thunder. Sometimes, it whispers through the courage to act, or the surrender to love.

This episode invites you into a deeply human and spiritual conversation—where reason and revelation meet the heart.

#godanautobiographythepodcast #jerryandabigailanintimatedialogue #spiritualdiscernment #divinerevelation #truecalling #spiritualgrowth #philosophyandfaith #moralcourage #spiritualpodcast

Related Content:

252. From God to Jerry to You- Hearing God Speak: An Agnostic Philosopher’s Awakening

249. Jerry & Abigail: An Intimate Dialogue – The Summons of Love and Life’s True Calling

Other Series:

The podcast began with the Dramatic Adaptation of the book and now has several series:

The Life Wisdom Project – Spiritual insights on living a wiser, more meaningful life.

From God to Jerry to You – Divine messages and breakthroughs for seekers.

Two Philosophers Wrestle With God – A dialogue on God, truth, and reason.

Jerry & Abigail: An Intimate Dialogue – Love, faith, and divine presence in partnership.

What’s Your Spiritual Story – Real stories of people changed by encounters with God.

What’s On Our Mind – Reflections from Jerry and Scott on recent episodes.

What’s On Your Mind – Listener questions, divine answers, and open dialogue.

Stay Connected

Share Your Story | Site | Facebook | Instagram | Twitter | YouTube

Scott Langdon [00:00:16]: This is God: An Autobiography, The Podcast — a dramatic adaptation and continuing discussion of the book God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin. He was a lifelong agnostic, but one day he had an occasion to pray. To his vast surprise, God answered — in words. Being a philosopher, he had a lot of questions, and God had a lot to tell him.

Scott Langdon [00:00:54]: Episode two fifty-three. On today's episode, Jerry and Abigail return for another conversation in our series Jerry and Abigail: An Intimate Dialogue. Jerry refers to last week's episode, where he recalls pondering the question “Why me?” So many times in life, people are being called by God to do something specifically attuned to their own path—something only they have the ability to do. And when it comes to love, it can be even more difficult if we're not paying attention and desiring to be in tune with God.

Scott Langdon [00:02:15]: This week, Abigail shares two stories about two distinctly different occasions where she felt certain, after much deliberation and prayer, that God was presenting her with something that had her name on it. Here's Jerry to start things off.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:02:22]: Hi sweetheart. Thank you for joining me for another dialogue. The last From God to Jerry to You, I raised the question “Why me?”—why God would pick me for this extended revelation that became a whole book, most of it God talking. It didn’t seem that I had any of the prerequisites. For one thing, I didn’t believe in God at the beginning.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:02:56]: When I revisited those early episodes, presented in dramatic form, what struck me was that the story really starts with falling in love with you. It was total romantic love—not compatibility date matching criteria- but total head over heels in love. And so I well, what is this? I had not believed in romantic love. Read the relationship books. What do they tell you? Don't trust it, don't believe it. It's projection. You think she's perfect six months from now, that'll evaporate. And if you're lucky, by then you'll be compatible, and you know, you can go on, stumble forward together. But, don't trust the love. And there's similar problems, you know. God spoke to me. I trusted it, and I did due diligence in both cases. I knew people make mistakes about love, and so I waited six months before actually proposing, though from day one there was never any doubt that's where I was headed. And with God, of course, nobody's infallible. People hear voices and visions and all of this stuff, including perfectly crazy people, but also people like Socrates and the great prophets and so on. But it just didn't seem that I fit the job description of having being a believer, having a kind of charismatic personality, because I've seen the movies and they're all with hair all over the place and eyes intense, and that's how we remember them down the centuries. They're people so charismatic that they remain charismatic for us, especially for people in their traditions, and I was just a guy. I mean, I was a philosopher, and so that's something, but it was, you might say, secular wisdom, and I had no God issue at all. But what I did do is have some trust. So when God spoke to me, and the voice was real and benign and authoritative, I wasn't a smart aleck. You know, I didn't think, oh no, this can't be. It violates my worldview. You know, I had a naturalistic sort of worldview. No, no, it doesn't have a category for God, therefore this can't be. I didn't do any of that. I just thought, huh, here something has presented itself in my experience, namely God, via a voice I heard announcing itself, this I am God. And, okay, I could hang on to my worldview and just say, God, get out of the picture, or I could open the worldview and say, there's more in heaven and earth ratio than are dreamt of in your philosophy, and that let God in. And I went that way. But as I thought about this more, and this is all in this podcast of the previous of last week, I guess, by the time this is run, I thought an awful lot of life, the question came up, and Scott Langdon and I were discussing it, how do you decide what to trust? And thinking of your daily life, you know, what should be the course of life that you take? What's what's your calling? What's your on any given day, what are you called to do? And we quoted something that you said, I think, in a previous dialogue we had, sweetheart, you're talking about some controversy you'd gotten into, and you said, “This fight has my name on it.” And Scott was asking, well, how do you know when something has your name on it? And I was thinking in part, well, when it comes to you that it does, however that call it intuition or a feeling or insight or whatever, you should start by trusting it. That doesn't mean you shouldn't doubt it and check it out and be reasonable. You know, we live in a big complex world, but you kind of have to start with trusting it. That makes sense to you, sweetheart?

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal [00:07:28]: Oh yeah, and it's a… there are all kinds of shadowy ambiguities at the outer borders of self-trust, so that it's very hard, if not impossible, to formulate a rule about it. Anything that would have the rigidity and scope of, say, Kant's categorical imperative.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal [00:08:02]: I think Aristotle, who’s more everyday in his relation to consciousness, talks about how to do the right thing in a situation as a matter of practice, good example, and a kind of hitting the bullseye that the archer knows about—because after all, that's why we call him an archer.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal [00:08:40]: Plato, maybe in the Phaedrus, talks about how it is that a student is deemed by his philosophy teacher to be ready for a step higher in dialectic. The teacher watches the student in real-life situations and sees whether he knows when to speak up and when to remain silent.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal [00:09:12]: And then, if he knows that in practice, in practical life, he's deemed ready to be taught the next stage on the ladder of knowledge bestowed by dialectic. But all these—even very finely attuned general rules—don’t quite cover the case that I myself am in when I'm in such a case.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal [00:09:49]: And I'm trying to think. I think of two examples. One had a moral action relevance, and the other had the “letting myself fall in love with you” relevance. I'll describe them both and see if we get any guidelines out of that—or just have to accept the fact that maybe there aren't general guidelines, but you know it when you see it.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal [00:10:31]: It was a moral case that came my way. I have had, in the time I'm describing, extensive personal family ties to a power structure in the Jewish state of Israel. My grandfather’s name is on a street in Tel Aviv; my uncle’s name is on the neighborhood of the parliament—the Knesset—in Jerusalem.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal [00:11:03]: And these relatives were extremely interesting. They’d been real players in real history, and I was tied to it through one aspect of my family. A young relative came to me with a story about her parents that was discreditable, and it seemed to me that somebody ought to call them on it.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal [00:11:51]: They needed to apologize to this young relative, acknowledge what had happened, and that it should never have happened. But I didn't want to do it, because this was a tie to a network that I had inherited through no merit of my own—a network of the most extreme importance to me.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal [00:12:18]: I did not want to call them on it. I sort of looked behind me and looked to the left and looked to the right. There was nobody but me to do it. I didn't want to do it. I went to sleep that night, and I had a dream in which these relatives, whom I loved, appeared to me in the guise of figures in the most intense spiritual danger.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal [00:12:53]: And I understood that if I do love them, I must write this letter. And so, having no choice, I wrote the letter in the morning and sent it off. And of course, it broke my ties with that entire branch of my family—and with it, my connection to a polity of the greatest importance to me.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal [00:13:26]: Because when I used to visit Israel, I would stay with them, but now I wouldn’t. And there was no other place to stay that would not have occasioned damaging talk within this network. I couldn't go there. It was a tie that I broke, and there was no one else to do it. There was nothing for it but to do it.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal [00:14:04]: So that's a negative case.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:14:08]: Well, shall I discuss that for a moment?

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal [00:14:11]: Yes, please.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:14:12]: Okay. Two things struck me about it. One was, you know, it's kind of a reasoning process. Here's something that needs to be addressed—a wrong that needs to be corrected or at least acknowledged. You can't repeal the past, so often there's a limited amount you can do, but facing honestly into the past—and especially people acknowledging their mistakes and apologizing to the person harmed by them—is an important thing to achieve.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:14:44]: A task needs to be done. Nobody else is stepping forward, nobody else is going to step forward—therefore, you might say, you get stuck with it. You didn’t volunteer, but it came your way.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:15:02]: The other thing that struck me—you could, of course, have said, “Well, it should be done, but there’s nobody to do it, and I’m not going to do it. Why would I throw away everything for this limited good?” But there’s another factor that’s rather generalizable: you did it for their good.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:15:25]: Something we don't realize sufficiently, I think, is that the person who's acting badly—ripping people off, lying, cheating, and so on—they’re really destroying themselves. You know, it's like The Picture of Dorian Gray. They're making their own portrait of their soul uglier and uglier.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:15:51]: And you want to save them from that. The way you can prevent that—when you’ve done something wrong—is to make amends, make apologies, recognize it honestly, and do whatever you can to make it up to the other person.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal [00:16:09]: Yes, exactly. Exactly correct. That’s to the letter what animated me—what made it impossible for me to sidestep this bugle summons. And the dream—heaven-sent—how do you get a dream like that?

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal [00:16:33]: But it ratified, it underscored the urgency, the peremptory requirement that there was nobody but me to fulfill—and if it went unfulfilled, it would do incalculable harm to people I loved more than the victim who had confided in me. I loved them more.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal [00:17:10]: So that's exactly what was in view. It was as dramatic as fiction, but it was real life.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:17:25]: Yeah.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal [00:17:27]: If I were a fiction writer of the kind who milks real life for stories, it would have made quite a story. But I was not a fiction writer, and there was virtually no one I wanted to tell.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:17:45]: Yeah—you told me that Spinoza sued his sister for cheating him out of money or something?

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal [00:17:49]: It was the inheritance. He was entitled to his fair share; she had grabbed it all. He took her to court and won a lawsuit that established the truth that he was a legitimate heir of his parents—and then he gave her the money.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal [00:18:24]: Once he’d won the lawsuit that established his right to the money, he turned it over to his sister. The point was to establish what was right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:18:34]: And I thought it might also have been for her good—but maybe that’s not part of that story.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal [00:18:42]: It might have been. There was a truth in the matter, and she was muddying the waters through which truth becomes visible. So he cleared up the waters and then gave her the money. It wasn’t about the money.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:19:36]: I always like to talk about falling in love—and I love it even better when you talk about it. But anyway, how does it come into this discussion?

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal [00:19:48]: Well, it’s a funny business, but it’s somewhat similar. The person involved—namely me—doesn’t want to fall in love because it’s a loss of control. I’ve got my life worked out. I’ve got a neat, rent-controlled one-room apartment on the Upper East Side within a ten-block radius that is home sweet home to me.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal [00:20:18]: I grew up there. I was born and raised there. I knew the grocer, the pharmacist, the museums were within walking distance. Who needs more? Who needs to die and go to paradise? I mean, I’ve got a place on the Upper East Side that’s rent-controlled!

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal [00:20:43]: I fall in love with you—I mean, I’m threatened with the prospect of falling in love with you. We spent an afternoon at the Metropolitan Museum, telling each other a lot about ourselves. You live in Washington; I live in my old neighborhood.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal [00:21:09]: We exit the museum, you hail a taxi, and you give me a goodbye kiss on the lips—which was an intimacy not taken before. It’s not a sexy kiss; it’s just a kiss goodbye, but it’s on the lips. You get into the cab, and I think, uh-oh.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal [00:21:41]: I go home feeling very threatened. I’ve got this life—it’s all worked out. There’s nothing wrong with it except true love, in which, unlike you, I’ve never given up belief.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal [00:22:02]: But you know, I’ve got my life arranged now. So I thought, let me get a truthful perspective on this. Let me get above this. Edmund Husserl has a technique called the phenomenological reduction.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal [00:22:21]: What you do is you bracket what appears to you in consciousness—you bracket the question of its relation to reality—and you look at all the appearances in consciousness as phenomena, as appearances to consciousness and nothing more.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal [00:22:50]: And that gives you a panoramic, wide-angle view from which you are disengaged. I thought, fine—let me sit cross-legged, I know how to meditate—and let me look at the feelings that are so threatening as mere appearances in consciousness.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal [00:23:18]: Let me practice this bracketing. So I decided to do that and put everything that had appeared to consciousness inside these Husserlian brackets. But it didn’t work.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal [00:23:36]: Instead of these appearing to consciousness, what happened was that my consciousness appeared to fall—like Alice in Wonderland—down a kind of slope without a bottom. I was inside, rather than detached from, what I’d hoped would be mere appearances, but was an actual new reality.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal [00:24:13]: I was conscious of it but unable to get a detached perspective on it. I was inside it—and I suppose, in fact, I did struggle to regain my former footing, as if hanging from the edge of a cliff. I thought maybe I could walk my way back up, maybe I’d just lost my footing—but it got me nowhere.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal [00:24:58]: I couldn’t get out of it. I was in it. I was in love. And when you’re in love, you’re in a new world. You’re not in a new worldview; you’re in a new world—textured, luminous, full of altered perspective. Your reality changes.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal [00:25:41]: I suppose if I could have lied up a storm, I could have talked myself out of it—but I’m not in the habit of being a capable liar. You’ve got to work on that; that’s a skill. I didn’t have it, and I wasn’t about to learn it just to escape the reality I was in.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal [00:26:07]: So there we were. I was in love with you, sweetheart. I didn’t mean to be—but I was.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:26:37]: When I went and looked, the love literature was hopeless. Those people often said nothing of any value at all. Maybe books that I haven't come across say something useful, so I don't want to generalize. But anyway, there was a rich literature on whether to trust a God voice. And it turned out a key to it is what kind of person am I? What kind of person are you? I'm talking about trusting, but the question is, am I trustworthy? You know, if I have this experience, am I generally a fliberty gibbet, you know, going after every weird thing? Am I on drugs, stuff like that? Am I drunk during this? Or am I someone who likes to dramatize my life? God spoke to me, you know. Well, it seemed I'm a kind of buttoned-down guy, sort of reasonable. And the textbooks always say if you hear voices that you're schizophrenic, but I didn't see any evidence I was a schizophrenic, and I didn't see how this textbook was going to adequately analyze Jerry without, you know, sight unseen. But with love, that's a big question. And I've certainly women friends I've known by both their experience and how they report other female friends' experiences. Gee, often they have a terrible time falling for the wrong guy, you know, one and sometimes one after another, and often the same problem. Can Abigail trust Abigail's feelings in a context like this?

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal [00:28:13]: There are people who have compartments inside their psyche where they put stuff they can't deal with. They'll tell you I don't want to hear about that, and then they'll put it in the compartment where they keep the stuff they can't hear about. I didn't seem to have a lot of closets in my mind. When I was ready to take early retirement and make a life together with you, I did ask for input from various experts at Brooklyn College. I did go from anthropology to sociology to psychology to, you know, um heavy hitters in each of these kinds of departments, women I knew, academics, who, without exception, told me that this is a very enjoyable delusion, and that in six months to a year, I don't remember, but it was certainly not longer than one year, I would recover and by no means I must not above all make the mistake of treating it as relevant to real life and the decisions of real life. Enjoy, you know, this temporary madness. It's fun and it's diverting and nothing better while it lasts, but it doesn't last, and you don't make plans based on this folly, this moment of uh welcome madness, that doesn't have much to do with real life. So the opinions I got were unanimous. Don't take any real life steps. So the question in my mind was, do I believe this is love? You know, as I report now, there was no place in my psyche, though I tried to generate such a place that afforded space outside the experience from which to make a judgment of approval or disapproval, I was inside it and not able truthfully to pretend I wasn't. So where sincerity was concerned, and that was the only thing I could get a handle on, to be sincere or insincere, I was certainly in love. The question of whether to reshape my life to make it accountable mainly to this new reality in my psyche. That was a question, almost the more momentous question. I could be in love and still be a friend, a philosophy prof, you know, whatever else I was on college committees or support the duties of my life without troubling those or discommoting them in one way or another. But if I were to make decisions that were irreversible based on committing the energies and future of my time in life to this new development that seemed to be, you've quoted me as saying, seemed to contain a summons– that I would call the summons of love. And it wasn't just an experience, it was a kind of demand, an imperative, uh, a call. If you really are in love, something in your life has to change and answer this call, shape itself so that this becomes dominant and uh trumps other duties. With love comes a duty to consecrate one's time and energies to whatever is the implication of being in love, which can only be discovered if once after you have devoted yourself to it, you have considered it a kind of calling.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:34:26]: That compel that has its own compelling aspect and calls for a distinctive response, and you let down the reality, or you pull back from it, fail to participate if you don't heed that call.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal [00:34:53]: My mother, as a young woman, was in Rome, and this is one of her stories, and she was rooming with a friend, a young woman friend named Regina. And Regina, in those days, the great Soviet experiment was new, and all idealistic people placed their hopes in their revolution. Regina was reproaching my mother for not devoting herself to this new movement in support of the Soviet 5the brave new world, the communist future that would redeem mankind. And my mother was tired of all that, tired of hearing about it, and she just inwardly expressed a kind of enormous impatience, didn't want to refute Regina. Regina incidentally later went to the Soviet Union. I was told, this might be apocryphal, that she became the tutor of Svetlana Stalin, Stalin's daughter, and eventually disappeared into Siberia or wherever you disappear when you have done your stint for the revolution. Anyway, my mother looked out the window, looked at the window as if where's air, where's escape, and had a vision of the profile of a man whom she didn't know, but it seemed to quiet her spirit. A couple of years later, she had gone to America, met and married my father, and he was sitting by the window and turned, his profile becoming congruent with the vision she had had, and it was so striking that she screamed, and so I knew from my mother's stories and her European friends that there was such a thing as true love. I knew there was that thing that was real. I also knew from the Bible, because the heroes in Genesis, the heroes of God's covenantal project, always had a true love and could hardly set forth on their trajectory through time and into history. Abraham had Sarah, Isaac had Rebecca, and Jacob, though, in the story he gets many wives and concubines, he had Rachel. And so, which was my mother's name, and so I knew that true love had objective heft in the history sometimes of peoples and also of persons, and that it was a thing of ultimate weight and seriousness, though in the America in which you and I lived, people didn't talk that way if they ever had. So I knew on a level that I had not integrated with other realms of knowledge, other sentimentary layers of knowledge. This was over to the side, but I took it greatly to heart. I took it with immense seriousness. I knew there was something else real, and I wasn't just being a fool, though if you know it could have turned out that way. I understood there is a risk here.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:39:09]: Do women understand that better than men?

Dr. Abigail L Rosenthal [00:39:30]: Yes. Women have other constraints, other vulnerabilities, other dangers and their lives to themselves and each other. On the womanly level they will be considered failures if they aren't living a true romance. And this is not acknowledged. The feminist revolution, which I certainly was part of and support, right deems itself above these so-called fantasies, which are treated as snares, traps, delusions by which women are caught and imprisoned, and certainly that is a real danger. So the situation of woman is not rightly mapped today any more than perhaps it has ever been, except in these examples that I've cited, and those only in part. So women surreptitiously, covertly have provided readership for the genre of romantic novels, bodice rippers, as they're called, bodice busters, in which the major drama has to do with women who play a consequential part in some earlier historical circumstance or situation, and also have as their supporting ambition and trajectory through the story a romance. And those novels, scorned, disdained by serious literary types, have a wide female readership, among whom I've numbered myself. I don't know if my sophisticated women friends read these things or not. This isn't something even the most honest female friendship necessarily talks about. It might on the slant, but not necessarily full face. We are deemed to be above it, but we aren't.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin: Well, that's that's a good point to to end on, sweetheart. We can we'll end it there and thank you again for an intimate dialogue.

Scott Langdon [00:43:02]: Thank you for listening to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. Subscribe for free today wherever you listen to your podcasts and hear a new episode every week. You can hear the complete dramatic adaptation of God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin by beginning with Episode 1 of our podcast and listening through its conclusion with Episode 44. You can read the original true story in the book from which this podcast is adapted — God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher — available now at amazon.com, and always at godanautobiography.com. Pick up your own copy today. If you have any questions about this or any other episode, please email us at questions@godanautobiography.com, and experience the world from God’s perspective — as it was told to a philosopher. This is Scott Langdon. I’ll see you next time.