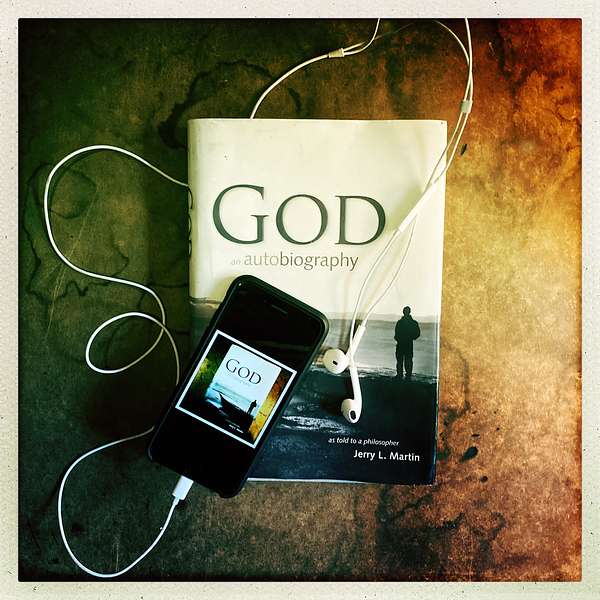

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

264. Jerry & Abigail: An Intimate Dialogue- Evil, Love, and God

In this year-end intimate dialogue, philosophers Jerry L. Martin and Abigail L. Rosenthal return to one of the most enduring questions in philosophy and theology: why evil persists, and what that persistence reveals about God.

Drawing on Jerry’s prayer experiences and Jon Levenson’s Creation and the Persistence of Evil, the conversation explores the idea of an evolving God—not as a denial of divinity, but as a way of understanding divine struggle, incompleteness, and ongoing relationship with the world.

Moving through Jewish thought, rabbinic midrash, and biblical interpretation, Jerry and Abigail consider divine ambivalence and the intimacy implied in speaking to God as a family member rather than a distant abstraction.

Abigail reflects on her own philosophical autobiography, "Confessions of a Young Philosopher," while Jerry situates God and Autobiography within a broader narrative of God’s interaction with cultures, histories, and individual lives.

The dialogue turns to skepticism and epistemology, questioning whether modern habits of doubt genuinely reflect how human beings know and live. Against intellectual posturing, the episode argues for sincerity, trust in experience, and the moral seriousness of truth-seeking. Love, in particular, emerges not as a distraction from philosophy but as a decisive mode of knowing—one that reshapes memory, reframes the past, and opens new ways of understanding both God and the self.

This conversation closes the year by inviting listeners into a deeper form of spiritual inquiry—one grounded in history, relationship, and lived truth rather than abstract certainty.

Other Series:

The podcast began with the Dramatic Adaptation of the book and now has several series:

The Life Wisdom Project – Spiritual insights on living a wiser, more meaningful life.

From God to Jerry to You – Divine messages and breakthroughs for seekers.

Two Philosophers Wrestle With God – A dialogue on God, truth, and reason.

Jerry & Abigail: An Intimate Dialogue – Love, faith, and divine presence in partnership.

What’s Your Spiritual Story – Real stories of people changed by encounters with God.

What’s On Our Mind – Reflections from Jerry and Scott on recent episodes.

What’s On Your Mind – Listener questions, divine answers, and open dialogue.

Stay Connected

- Read the book: God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher at godanautobiography.com or Amazon

- Share your questions and reflections: questions@godanautobiography.com

Share Your Story | Site | Facebook | Instagram | Twitter | YouTube

Scott Langdon 00:00:44: This is God: An Autobiography, The Podcast — a dramatic adaptation and continuing discussion of the book God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin. He was a lifelong agnostic, but one day he had an occasion to pray. To his vast surprise, God answered — in words. Being a philosopher, he had a lot of questions, and God had a lot to tell him.

Scott Langdon 00:00:58: Episode 264. Welcome to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. I’m Scott Langdon, your host, and this week Jerry and Abigail return to round out our year with another intimate dialogue and deliver a really intriguing look at why and how God allows evil. How can we account for what seems like God’s ambivalence? And what’s love got to do with all of it, especially when it comes to our desire for truth?

Scott Langdon 00:01:39: Also, this being our last episode of the year, I’d like to take just a moment to say how grateful we all are to have you out there listening. Have a happy New Year, and we’ll see you next week with plenty to come in the year ahead. Here’s Jerry to get the conversation started. I hope you enjoy the episode.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 00:02:06: Well, thank you, sweetheart, for joining me in another Intimate Dialogue. Intimate, but not overly intimate, because we have guests here with us, and we have serious matters to talk about. My last From God to Jerry to You was about what I think of as the climax of God: An Autobiography. It’s not until close to the end of the book—not the very, very end, but chapter 68 out of 70—that I start realizing, having read Jon Levenson’s book Creation and the Persistence of Evil, that the things he’s saying seem to be what God has been telling me.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 00:03:09: And so I give God six of my own takeaways from Levenson's account, which is an account of the Old Testament—a careful reading of the Old Testament—Creation and the Persistence of Evil, that evil doesn’t quite go away. God keeps fighting evil.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 00:03:26: And the surprising thing—and I know you’ve been reading this book as well, sweetheart—it is a surprising book, I have not read this anywhere else. He’s a big professor at Harvard. He certainly knows his stuff. But the key point, which was number three in the list in that chapter, is that there is a negative or incomplete side to God, so a lot of the key to why evil is persistent is that God isn't totally pure, totally perfect; there's a negative or incomplete side to God.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 00:03:56: I was discussing this with some of the team that puts on the God: An Autobiography The Podcast, and people take it differently. How did you take it? I’ll tell you how I took it, but first I want to hear how you took it.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 00:04:14: It’s not unfamiliar to Jewish thought and experience. And I think Levenson’s subtitle doesn’t reference just the religion of Israel of the biblical period, or core to Judaism, but also the subtitle has the word Jewish is in it. Rabbinic Judaism, the Judaism we know.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 00:04:43: There are all kinds of anecdotes, midrashim, which are half fanciful and half ironical, and they somehow capture, in a Jewish equivalent of a haiku, this strange (acceptance) familiarity with God’s ambivalence.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 00:05:11: One such anecdote has God answering the query of Moses in the afterlife: who best understands Me, Moses, now? God whisks him along 135 of the Common Era, where Rabbi Akiva is teaching in a rabbinical school.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 00:06:02: Moses says, “I don’t understand.” He’s teaching about Mosaic thought, and Moses doesn’t understand a word of what he’s saying. And God says, “That’s okay, he understands you.”

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 00:06:38: So, there’s an ironic acceptance of the fact that in reading biblical experience, we don’t read as archaeologists. We read as the people we are now, delving into the continuity of changing experience. It doesn't change so dramatically that we don't see ourselves in it. But we're not archeologists, we're not doing time travel.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 00:07:08: In the same rabbinical midrash, haiku as I call it, God spirits Moses and shows him what befalls Akiva. Akiva has backed the wrong pretender to the Messianic claim and the Bar Kokhba uprising that was disastrous for the Jewish people resulted in their second exile. Akiva is nailed to the flooring and being skinned alive. Something you don't even want to visualize.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 00:07:54: And God says, “This is how I treat my friends.” And Moses immediately answers back, “That’s why you have so few of them.”

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 00:08:18: You don't talk to somebody whom you hold in nothing but all for the transcendent. You talk like that to your mommy. You know, that's how you talk with the most familiar, loved people whom you reproach for not coming up to your needs. But you don't reproach for being themselves...

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 00:08:45: Well, when someone lets you down and you know them well, you’re not necessarily surprised. You know that’s how they are. Well, sometimes he's helpful, sometimes he's out to lunch or whatever. Okay. And you kind of know that going along. And well, okay, that's brother-in-law. So, you know, you live with it. He's a good husband to my sister or whatever. That’s an intimate, family-type relationship.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 00:09:12: God is family. It sounds arrogant to postulate that, but it isn’t experienced in a mood of arrogance. On the one hand, you don’t want to be an orphan, isolated in the vastness of the human population. On the other hand, family is not an unmixed blessing. A lot of family, you don't want the world to know as much about as you know.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 00:10:03: Another side to that story, to God's incompleteness or lack of fulfillment. He's not quite fully God, you might say, not fully in command. And therefore, evil has this power, you know, is almost like periodic floods or monsoons. Here comes evil again, and God can't quite control them all in part because they're an aspect of God.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 00:10:42: It didn’t seem to me that God has a wicked or malevolent side. As it developed in my prayer experience, it seemed more that God was unintegrated. An awful lot of our glitches and faults have to do with our different parts aren't working together, so sometimes we kind of are. And at other moments we aren't because some other part of ourselves kicks in and determines our behavior. And so we run and hide or, you know, we have all these different aspects. And even at the organic level, a lot of organic problems is the thyroid and the kidney aren't working together, right? I'm going through something with doctors. I should drink more water. But on the other hand, another doctor says you have low sodium, you should drink less water because that sort of dilutes it or something. Okay. Well, these parts, the things don't all integrate harmoniously the way they do in a wonderful musical group or orchestra or something. Everything works together, and God is in the middle of all of that, and God, in some sense, is all of that, being the pushes and pulls of life and reality are God's life. And it's evolving.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 00:11:12: Even at the organic level, illness often comes from systems not harmonizing. Parts aren’t integrated the way they would be in a well-functioning orchestra.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 00:11:59: God is in the middle of all of that. In some sense, God is all of that—the pushes and pulls of life and reality are God's life. And that life is evolving. I mean, that's why the story doesn't just stop there with a kind of a snapshot.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 00:12:28: One of the first things, I was told in prayer—before I ever read Levenson— that had puzzled me totally at the time-- was, “I am an evolving God.” That didn’t fit any idea of God I had ever had or heard of, but I just wrote it down. Evolving. God is changing.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 00:12:48: And what came out became clear to me before reading Levinson, well Levinson crystallized it: how does God progress? You know, what is God's story? God told me, "I want you to tell My story." What is that God's story? Well, it turned out a lot of God's story is how God's interacting with the religions of the world, the cultures of the world, the different peoples of the world, with the different individuals in the world. And God's story is the story of God's interaction with us, and we are kind of intimate with God, and we have God inside, we have God outside, and we are intimate, and we are interacting. The Old Testament, of course, is one story of interactions, but the others are also stories. The Mahabharata is a story of human interactions with the divine.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 00:13:35: God, like people growing up and going through life, and you have different family events, different relationships, and you learn something from them, hopefully, and you kind of grow. I've been thinking recently about some friends who went through tragedy-- terrible, terrible tragedy. And I noticed right away, he is deeper now. Another dimension is added to his character. And that story has its own evolution. It would be too personal to describe it, but that wasn't the end of the story.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 00:14:16: Having gravitas, you know, having a kind of deeper sense of life, but it's led them to certain actions that come out of that. Well, this is how it happens for God. You interact with people, you grow, you learn about yourself. When the Taoist reacted to an aspect of the divine in the way they did, God says, 'Oh, it's like I hadn't noticed that about Myself.' and this is something that happens to us as we go along in life. Someone reacts to us in a certain way and they say, 'oh, you're very funny.' Well, maybe you hadn't realized you were funny. But now, oh, really? That kind of helps you be funny, you know? It helps you actualize yourself.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 00:15:37: Something analogous, you were told by God that the old religions, the group that we know with all the well-known names that you study if you're a religion major or going to be a theologian. The latest thing back when... they were first revealed to their teachers and promulgators. But God has moved on. History has moved on. The human race with its experiences and its new communicative almost promiscuity. We all know each other's business from, you know, China to the Philippines, down to Buenos Aires, wherever there is something to be known, we can get connected. So, all that is so different from how the God-human relationship first took its various shapes in discrete and mutually opaque cultures around the planet Earth. The whole thing is due for an upgrading, for a modernization.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 00:16:12: That means the relationship itself is due for an updating, a modernization. And your conversations with God, in God: Autobiography are laying the foundations of those new relationships which are now to be worked out. And analogously, I was thinking in my own case... it's odd you know it sounds almost vainglorious to compare one's own personal autobiography to God's autobiography, which is, as I said, the title of the book you wrote, God and Autobiography as Told to a Philosopher.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 00:17:14: In my own life—though it sounds vainglorious to compare autobiographies—I spent decades trying to get back to how I used to be, trying to climb back up the staircase of my life with solid steps under my feet.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 00:18:01: At some point, perhaps after finishing my memoir Confessions of a Young Philosopher or some sedimentary layer in our own mutual experience or some combo of all those and more, I felt as if: I have got it. But I get the point about the past, about all those sedimentary layers that underpin my foothold, my standing firmly on the life's ground floor.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 00:18:58: What did you learn? What did you discover?

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 00:19:03: It’s funny, because I often say—ironically—as I’ve gotten more superficial. What I really mean is that I’ve become more transparent. Now what you see is what you get. I'm quite shallowed out. What did I learn? Uh... I think I could encapsulate it.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 00:19:36: The human relation to God, my own included is chronological. The optimal human relationship to God, the one that a well-integrated human being ought to arise to, and God agrees to enter, the optimal human relation to God unfolds chronologically one thing after another in time (I had this insight years ago, but I seem to have grown into it, and now integrally believe it) is historical, is temporal, is what's happening now. And what happened within relevant memory, relevant to what we're doing and what we're up to at present, and foreseeable advances subject to modification, but to be gone toward on the basis of where we are now. So, a kind of visibility of ourselves to ourselves, and of ourselves to the God who sees us, seems to be what I've (without sounding too pretentious) what I've attained. You know, what I've come to, what I've climbed up into. Though I had the concept for some years, I seem to now own it, not just conceive it, but really sincerely live that way. And it means that I don't need to track behind me or revisit incessantly the earlier layers.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 00:21:56: So you don't need to carrier past like a string of tin cans, people sometimes say, 'you know, tied to the cat's tail or something, dragging a bunch of tin cans. And the past can be that. I always, myself, think longitudinally. And I think both that I have a long past. I didn't just pop out into existence two minutes ago, after all. Everything I am is what I've been, you know, what I've come through that process.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 00:22:29: That's kind of questionable. Then what, I guess, the question is: What is the fruitful relation to one's past? It's not that you should live like an amnesiac, that you don't remember what happened or, you wipe it clean. There might be times people go through some horrible trauma. The best thing to do is just wipe out the memory. Just wipe it clean or forget the Great War, because it wasn't that great. So let's just not revisit that part, even though maybe you've revisited in your nightmares. But on the whole, one wants to remember one's past. You remember growing up, and that's sort of a good thing to do, and often revisiting growing up, what it was like in your home and with your parents and your neighborhood and your school, you learn something from going through that process.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 00:23:25: But we might also think about, again, God's perspective. God says, 'I'm an evolving person.' At some point, when I was praying about something, like in the book of Genesis or something, God says, 'Well, I was young then.' It's as though, well, yeah, I was kind of rough. And bad-tempered and I don't know, a little inconsistent and so on. Well, I was young then and was just learning how to deal with people. And so it's almost like you look at your own childhood or teenage years or something while you were young. So you lurch this way, lurch that way, and then you slowly learn from your mistakes, and you slowly grow up and mature. Well, God went through that, and it's with people. and He's going through it. His job is more complex than ours. I say His, though God is his, her, and other, you know, all combined somehow.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 00:24:52: But going through this with multiple cultures, each one has its own youth. You know, we tend to think of the cultures as ancient, as though they were old and wise, but actually they're quite young. You go back to Egypt of the pharaohs. They're very young in terms of the human story and in terms of interacting with the divine or the, you know, I kept trying to find the origins. Everything has to start somewhere. I wanted to read about prehistoric life and so forth. What we can deduce from what people buried, for example. They seem to believe in an afterlife because they buried the men with their spears and the women with their jewelry. So these patterns go way back.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 00:25:40: Long-preliterate. And then the oracle bones where they put the bones in a flame and they would crack in a way that resembled what became Chinese characters. The seers, whoever they were, would interpret it. This an auspicious day to do such and such. When people and God are very young, and God is learning from us about the different aspects of God.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 00:26:15: And, you know, you think of your memoir, sweetheart, Confessions. You go off to Paris as a young woman ready for life. What better place to encounter life than Paris, you know, of all places. And well, you have experiences that are positive and negative. You learn from that. There is a childhood story of Abigail, but your, you might say, adult story begins with that youthful experience in Paris, but it doesn't stop there. It's not as though you revisit that endlessly. I noticed when we were first together, sometimes when something new would happen you would relate it. You would kind of figure out, oh... How does the past look now? One of the things about new experience is that it redefines the past. So now the past doesn't look the same anymore in light of it came out here, which is maybe quite unexpected. And that's happening to God, too. I guess that's part of where I was leading. But in terms of ourselves, that may be one good way to deal with it. I don't do that. But it seemed like a very fruitful way to connect your current self to your past self or the current moment to past episodes that are relevant to your current moment.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 00:27:51: Yeah. It’s funny—I had a method. It's not original with me. It's the dialectical method. And I used it in most of my adult life until you and I met. It might have been a little before we met, or it might have been a consequence of your experience with God, but I did not so much have recourse to the dialectical method in charting my own course after that. It was more a personal prayer relationship...

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 00:28:47: Say a little more, if you would, sweetheart, about the dialectical method. What is that like? How were you living before? And this is somewhat typical, you might say, of a philosopher-type person or many intellectuals. You have some rational method that you use to figure out your life to make decisions.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 00:29:15: Socrates introduces our civilization to the dialectical method. He asks his interlocutors that the people he sort of buttonholes on the street of Athens, what their animating motive is, what they think their life is about, what guides their footsteps through. each day, and they state the rationale of their lives. Perhaps nobody's asked them to produce a rationale. One has this experience as a teacher, you familiarize your students with a concept of the rationale that guides a particular life, the reasons for it, the purposes semi-articulated that you're pursuing.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 00:30:25: By the same token, often, this effort helps one identify the purposes that the whole culture seems to be pursuing. So that you can either localize yourself as a member in good standing, believing what intelligent people today believe. Or identify yourself as somewhat outside the norm but put the intellectual props under yourself. I think otherwise, but I have the following reasons for how I think.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 00:31:16: There was a certain point in my life as a young assistant professor of philosophy, where I thought, I'm home free. Philosophy is the queen of the sciences. I have the great honor and privilege of ushering young people into the courtyards of philosophy, which will help them live meaningfully and be aware of their lives and the animating principles that so far have guided them and be able to revise those principles when the need arises. So all was well. Until in order to keep my job... It was conveyed to me that I had to vote a certain way which would have contradicted by my better judgment, my personal assessment of that certain way if I wanted to continue to teach philosophy.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 00:32:23: Some crumb. Vote for some incompetent because the powers that be in the department were choosing that person maybe is their instrument or whatever. But anyway, they were lining up for that and you and some others. Who alas should not have tenure. I thought this was a very poor judgment. And you all get to vote the way you want to vote (theoretically).

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 00:32:29: So I knew, as I was asked a leading question by a senior professor who held an as yet unwritten, evaluation of my teaching in his pocket, why I thought this professor was backing this substandard candidate for the post, the very responsible post of chairman of the philosophy department where I taught, and had all my life worked out. And I thought, if I lied which is only tactical I can't represent the philosophic pathway in life to my discerning, all too cynical, life knowledgeable students. You know, students in their very late teens, 18, 19.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin: You always talk about these Brooklyn students as if you can't fool them, they detect a fraud from a mile away and you lose all credibility.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 00:34:23: You can't talk about, somebody I know described it as beautiful and sacred things, if you're doing something ugly. Because they can see ugly, a mile away, they can smell it. Cynical, world-wise, street-smart young people. You just don't want to be seen through. I don't mind grownups seeing through me, but these kids, no.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 00:35:06: You have an obligation to them. The grown-up next-door neighbor, you don't have that same obligation, but you're teaching them philosophy. Philosophy is the love of wisdom, pursuit of truth. Did you tell the senior professors?

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 00:35:21: Oh, he asked me why I thought if the candidate he was backing was as unqualified, as I had said he was how could I explain a man like him, the Senior Professor, voting for him. I had a couple of seconds to view my life going down the chute. There goes that job. There goes this wonderful perch that I have climbed up to in life. But on the other hand. I could see the eyes of the students as they would have appeared had they been looking at a phony. And I said, 'I just can't explain it, dear colleague, except on the supposition that he's weak, and you think you can use him.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 00:36:27: So, you knew the tactful answer, but the tactful answer was not the truthful answer. You knew that if you wanted to keep your job the tactful answer would be wise, but you had another goal. You certainly wanted that job. But you had a second goal that outranked it. You've got to be truthful if you're going to be a philosopher and a philosophy teacher.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 00:37:01: Yeah, very sad. There went that job. There went the next seven years while I'm fighting to get the job back. And everybody's saying, 'Give it up. Don't be obsessive.' And I'm thinking, I don't know how this story ends, so I'm not going to give it up until I find out. In that experience, was it a piece of the dialectical method or not? It was in the sense that if you believe X, you better prove it by acting as someone would act who believes X. If I believed that philosophy was simply a very high, if not the highest calling, certainly the highest calling available to me, then I had to act on as high a level as was available to me. And being a phony would not be consistent with that. So in a sense, I was living dialectically. I was doing and acting as I professed to be, to have as a purpose, as my professed purposes would have me act.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 00:38:44: So that's a rather complex intellectual assessment, you know, playing out options. And you were saying that you used to live dialectically and then, around the time you met me, that changed. And if you can say something about what the change was, what was the difference, what's your new way, which I guess is your current, right?

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 00:39:12: Yes. Although I haven't jettisoned the dialectical method, if it's good enough for Socrates, it's plenty good for me. I think it's good for anybody. You ask, you know, under what concept of going forward, or the next step. Are you in fact going forward? How does the culture reflect or jar against that concept and those are relevant methods for living intelligently and truthfully and transparently. So I haven't surpassed them as I don't think one can. Socrates laid it out. You know, the old guy was right. But something else happened.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 00:40:38: I'd always thought, and dialectic is partly about human desire. If you hold something as your purpose, but you don't desire it. There's a discrepancy there. So the relation between a dialectically arrived at purpose and your own— a medley of desires, your own inner life of desire—ought to be a close one. Or else you're living with this gap. You profess to a spouse some particular value or principle. But you, the desirous you, really doesn't. You're hanging back or you're wishing you were elsewhere. So I have taken seriously from the very beginning of my adult life, as soon as I could draw these distinctions, the life of desire. I've thought no, you have to honor what you really want. and line it up. with the concepts you profess to value. I had always valued true love.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 00:42:09: And I had always valued the prototypes of true love that are in Genesis, the first book of the Hebrew Bible, I don't know if there's anything analogous in the entirety of the New Testament, but the Hebrew scripture is about living on the timeline. You know, some of the incidents may be fanciful, but they relate to life on the timeline, even the conjured up ones are evocative of what goes on with your feet on the ground, one step in front of the other, and the founders of the peoplehood that would live in a conscious relation to God as a real witness and a real co-player in the human story, all had a romantic life. Which seem to supply the erotic preconditions for their desire to do God's will, their desire to live in accordance with the will of the highest being. So I had always taken that seriously, very seriously. And I thought, this is of universal import. Everybody wants a true love.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 00:43:56: If you acknowledge and admit and recognize that this is what you really want. I mean, there may be some people I'm not taking in who don't. Surely there are. But I thought most people do, whatever they're culture, I thought this is kind of general. Most cultures have some romantic story in them. So I thought I should take this quite seriously.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 00:44:29: And when I met you and began to notice that this was serious, which was sometime after everybody else noticed. I was busy. We were working on saving the college where I taught. So I was busy with the college where I taught. And only entertain the relation to you in my conscious awareness in that connection. But we had perhaps met once or twice personally by that time, in person for the first time, and talked at some length.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 00:45:19: You'd exchanged with me the most chaste of kisses before getting in, climbing into a taxi and riding off to train back to Washington. And for some reason, this very superficial kiss, very surface kiss had the power, had an imprinting power. And I thought, uh-oh. Ts is more than I bargained for. This is more than I expected to have to handle. But on the other hand, I can't lie to myself. So I thought, well, let me try to get some distance on it once I got home. I had a few conversations, maybe with friends, but mostly I thought, I need to figure this one out. I need to stay in command of my life if I possibly can; I'm a philosopher.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 00:46:33: So let me use one of the philosopher's techniques called the phenomenological reduction, offered to the world by Edmund Husserl. You take a step back from your experience and you bracket the question of its relation to reality.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 00:46:58: You just look at it. You gaze at it. These are appearances in consciousness, phenomena. It's called the phenomenological reduction. I thought, let me look at it through the lens of the phenomenological reduction, bracketing the question of how real this was and how this might relate to my destiny in real life. And what happened was that trying to look at my attitude and memories and current experience with you, I could not look at it with the requisite detachment that belongs to this technique.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 00:47:51: Instead, gazing at it, unencumbered by presuppositions left or right I found myself tumbling headfirst into it. And I tried to tumble back out of it. That did not work. And, you know, I can't lie to myself. It's not worthwhile to have any experience accompanied by an all too generous dose of self-deception. You try to live honestly. And you can tell when you're lying to yourself, it feels different.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 00:48:38: I thought, well, I seem to be in love without a means of falling out of love. Oh, God. And if so... then I need to see what belongs to this. Love has its own demands. From biblical experience, from my parents' life together. I, perhaps unlike a typical modern person, took love very seriously.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 00:49:21: I had long thought that that's what is optimal in life, and that's what people secretly want. Okay, here it is. I didn't plan on this. I've got my life worked out. Love didn't ask me whether I had my life worked out or what my plans had been before it showed up. So. In a sense, I was living dialectically in that: an unplanned, unlooked-for, but equally undeniable reality suddenly took over the ramparts and the middle parts and the details of my life. And they recast it within a new picture frame, as it were. They retold the whole story of my life. But now differently. Vis-a-vis this new frame.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 00:50:26: And obvious to me, was the implication, with love, you look at life differently. The same dialectical obligation to be true to your experience still obtained except with the sole difference that Socratic, I mean, the difference, which I didn't know would be a difference, with Socratic dialectic, normally, or at least generally speaking, you come to the edge of some guiding concept and you realize the concept is inadequate to manage life in the light of some new and further experience.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 00:51:20: But Socrates doesn't come to the end of the concept of the love of wisdom. That is the guiding, in a sense, you can say the end of the journey. And in the, I guess you could say "en passant, in my voyage", animated by the love of wisdom, I came to an experience. That doesn't contain its own terminus, its own inbuilt limits it. I was willing to try it. Maybe it'll have inbuilt limits. But it seemed to me, if we encountered those limits honestly, together, We would recognize that we had been proceeding under some artificial limits, or other, or non-necessitated limits. And we would. Transcend those limits. That there wasn't anything in our relationship that involved...

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 00:52:37: The love seemed to have more depths than limits. You know, just one could go in deeper and deeper. I had this experience as you were going through just what you described, sweetheart. I, at my end... us going through I'd never believed in romantic love. I thought I was looking for companionship of the sort of dating service is nice at giving you. I had a Myers-Briggs profile in mind. This is the kind of woman I need. And this had no relation to any of that. It was head over heels and full romantic love. And I didn't understand it. What is this? And so I read the relationship books. What can the psychologist tell me? Well, they all said, I think a lot of your colleagues said things like this to you, but here are the experts were saying it: it's deceptive. It's delusional. It's a projection. It's all projection, projection, projection. It will last for about six months, and then it will dissolve. You'll think she's perfect. And you'll find out she's not. No, I did not think you were perfect. I'm not perfect. Why do I need perfect? It had nothing to do with being perfect.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 00:54:11: And learning from it, being truthful to the experience. Often what I was tending to do as a less dialectical philosopher was just., as a kind of logician trying to figure this out, well, that didn't really get me anywhere. And the only thing I commend myself for is, well, poo on logic then. If it's not helpful for this, then don't use it for this. And what will be helpful. And, of course, that's what led me to pray because I felt gratitude. It wasn't help for me. I just felt gratitude and prayed. And, you know, the story of God: An Autobiography takes off from there.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 00:54:58: And that's why I'm an epistemologist. So, I developed, this is in my book, Radically Personal. An epistemics of trust, if you read the epistemologists, they're all based on Cartesian doubt and Hume's skepticism and so forth. They don't even know if there's a world around us. Maybe we're a brain in a vat, some of them say. All this kind of thing. There's an evil demon orchestrating illusions.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 00:55:27: Well, no, you're not going to get anywhere if you just start with doubt, doubt, doubt. If you doubt everything, the way knowledge actually works, if you look at knowledge, knowledge is a phenomenon one encounters and we have all these different disciplines that know things about history, about physics, about old plants, and so forth. And you trust your senses, you trust your memory, you trust your reasoning. You then correct them by further checking, your experiences, other people's experiences, checking your memory against records, checking your reasoning. Have I made a mistake here? That's one reason for engaging other people. You know, here's how I'm thinking about this. Does this sound reasonable to you? And see, oh no, I think about it differently. Okay, but you can't do any of that unless you start with believing your experience, your memory, your reasoning, and so forth. And I don't see how you'd ever have a life of true love if you didn't credit the experience up front.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 00:56:34: And that's not so dialectical. I mean, it's not immune from dialectic because it can run amok. You can say, 'Whoa, this head over heels thing.' You often talk about dialectic as you find out what its limits are, something's limits are. You have a worldview, an attitude, a thought, and you kind of test it against experience, against life unfolding. Sometimes, you learn what its limitations are. Maybe it's true in a bounded way, but not as true as it seemed. Then you learn that and correct it. So that's also a learning experience. But this basic attitude of first, give yourself to the experience. Learn all you can from within the experience before deciding it's reached its limits. Don't declare its limits before you reach them.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 00:57:35: If you love truth, why go into the love of wisdom, which is what philosophy means in Greek if you don't? Supposing you know yourself well enough to know that you really love to find out what is true, you need to find out. You think it's worthy. Of yourself, you have an opinion of yourself, that you and the truth can live together, and something happens to you that doesn't present some of the earmarks of delusion or self-deception. Then you follow it. You follow it.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 00:58:58: A recent 20th century essay by the English philosopher Mary Midgley points out that in order to say 'I think, therefore I am,' you have to say it, which means you have to speak it, which means you have to make use of a language. And babies, infants, very small children learn language almost before they know that it applies to themselves. So the first thing is not, I think, therefore I am, but you say something to me and therefore you are. And by extension, I am. I probably am. You know, they make an inference later. Oh, I'm like the little kid who threw that ball at me. You think, therefore, you are. And maybe I think, therefore, I am. Or you speak, therefore you are. So. A lot of these skeptical postures come from posturing. Come from pretending to doubt what you actually and sincerely and authentically do not doubt and cannot doubt. How about starting more naively with what you don't doubt.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 01:00:35: Right, and that's more truthful. Claiming to doubt or to be ascetic or everything's got to be proved to you is, well, as you put it, it's a kind of posture. A stance that you're adopting. It's not truthful to what you really think. You bring out an umbrella to stop getting wet. Is rain real or anything like that? But then the people you see. And you're right, the child's first understanding is something seems like a unified mother-child world. You know, they're not differentiated at all. That slowly has to be learned. It doesn't start at all with the I. The I has to be learned in contradistinction to the you. They're learned simultaneously, in a sense, as you differentiate experience. The child has to learn that mommy also has feelings, and you learn that by mommy expressing them. So, oh, and that's how you learn that you have feelings.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 01:01:42: Because the mommy says, 'Oh, your foot got hurt here, and let's kiss it and make it well.' Oh, yeah, kiss it and make it well. And that's how the child learns, oh, yeah, I have a pain in my foot. By these social interactions.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 01:02:08: Yeah, they are prior. Evidence apparently that's beginning to unfold of the consciousness of the child in the womb. That would suggest, more than suggest. That the child's initial experience is a co-experience, a partnership, a duality. You don't necessarily say it's her and me, but you say something.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 01:02:35: You don't know how to say it in terms of persons. You don't know how to even count how many persons are here now. If you've just got this rudimentary, not yet born, you know, child coming, is that another person? Well, it's the same person as the mother still, you know, biologically integral, the nutritional apparatus. It's all the same as the mother. That's amazing.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal 01:03:05: Mary Midgley points out these obvious truths. These almost—though not—self-evident in the logical sense. They're as evident as anything and points out that the skeptic is making an end run around what we all know. It's almost a tour de force. The pretense of skepticism. We live in a highly pretentious era where skepticism claims to dominate the thinking of the most influential pundits who style themselves philosophers, though I think, Socrates wouldn't lift a wine glass with them. They're not part of his symposium. But they claim to be the latest thing. And if that's anything like accurate, the latest thing is simply an empty claim.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 01:04:32: Yeah, very disappointing upshot. It's too bad. It can't be how they themselves live.

Dr. Abigail L. Rosenthal: No, it isn't. It certainly isn't. The culture needs to shed these habits of pretentious and hypocritical posturing, this pretense of being intellectual where you believe what nobody believes or you claim to believe what you in fact do not believe and neither does anybody else; and try to get sincere.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 01:05:19: Yeah, it passes for sophistication. But sophistication is not as good as basic sincerity, i. e., being truthful to what you really think and feel.

Scott Langdon 01:05:43: Thank you for listening to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. Subscribe for free today wherever you listen to your podcasts and hear a new episode every week. You can hear the complete dramatic adaptation of God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin by beginning with Episode 1 of our podcast and listening through its conclusion with Episode 44. You can read the original true story in the book from which this podcast is adapted — God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher — available now at amazon.com, and always at godanautobiography.com. Pick up your own copy today. If you have any questions about this or any other episode, please email us at questions@godanautobiography.com, and experience the world from God’s perspective — as it was told to a philosopher. This is Scott Langdon. I’ll see you next time.