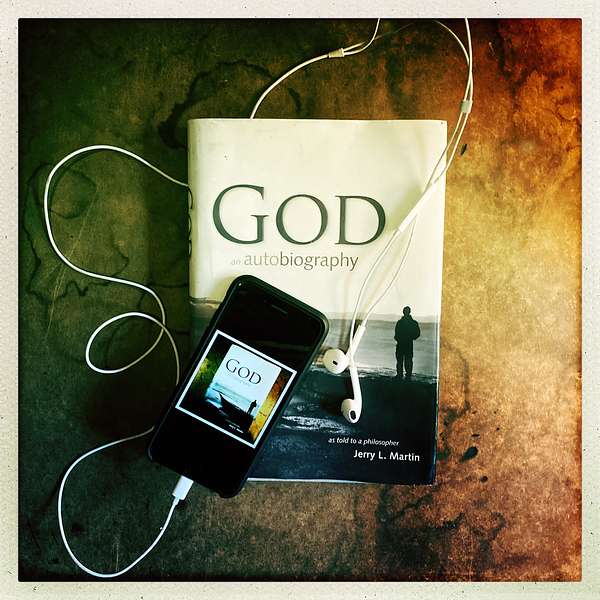

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

267. What’s On Our Mind- God, Evil, and the Meaning of “Knock and You Will Find”

In this episode of God: An Autobiography, The Podcast, Jerry L. Martin and Scott Langdon reflect on what it means to live in partnership with God in a world where evil persists and meaning is still unfolding.

Drawing on biblical scholar John D. Levinson, they explore order and chaos, the idea of a developing God, and how discernment shows up in lived experience.

Referencing William James, the conversation turns to faith as embodied wisdom rather than rule-following, and to Jesus as an unfiltered expression of divine presence.

Through reflections on ego, power, tough love, and the teaching “knock and you will find,” the episode contrasts horizontal and vertical ways of seeing reality, suggesting that seeking itself may already place us within the Kingdom of God.

Related Episodes:

263. From God to Jerry to You- The Problem of Evil and the Kingdom of God

264. Jerry & Abigail: An Intimate Dialogue- Evil, Love, and God

265. Radically Personal – William James on Religious Experience

Other Series:

The podcast began with the Dramatic Adaptation of the book and now has several series:

The Life Wisdom Project – Spiritual insights on living a wiser, more meaningful life.

From God to Jerry to You – Divine messages and breakthroughs for seekers.

Two Philosophers Wrestle With God – A dialogue on God, truth, and reason.

Jerry & Abigail: An Intimate Dialogue – Love, faith, and divine presence in partnership.

What’s Your Spiritual Story – Real stories of people changed by encounters with God.

What’s On Our Mind – Reflections from Jerry and Scott on recent episodes.

What’s On Your Mind – Listener questions, divine answers, and open dialogue.

Stay Connected

- Share: questions@godandautobiography.com

- Get the books: God: An Autobiography, Radically Personal

Share Your Story | Site | Facebook | Instagram | Twitter | YouTube

Scott Langdon [ 00:00:17,220 ]This is God: An Autobiography, The Podcast — a dramatic adaptation and continuing discussion of the book God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin. He was a lifelong agnostic, but one day he had an occasion to pray. To his vast surprise, God answered — in words. Being a philosopher, he had a lot of questions, and God had a lot to tell him.

Scott Langdon [00:00:59,240] Episode 267: Hello, and welcome to God: An Autobiography, the Podcast. I'm Scott Langdon, and I joined Jerry Martin this week for our regular series we call "What's on Our Mind." One of the reasons we continue to do this series is that I always have so many questions and thoughts about the episodes we've recently produced that have to do with the practical reality of living a life in communion with God that I just have to ask Jerry about them. In today's episode, Jerry and I talk about our relationship to God and the world and discuss John D. Levinson's explanation of a horizontal and vertical point of view when examining this strange duality. We also talk about Jesus and how he was, as the late Marcus Borg put it, what a life filled with God looks like. Here's What's On Our Mind. I hope you enjoy the episode.

Scott Langdon [00:02:12,750] Welcome back, everyone. This is What's on Our Mind. I'm Scott Langdon, and I'm here with Jerry Martin. Jerry, it's great to see you this week. We have a lot of really good things to talk about.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:02:23,110] Well, I was looking back at these recent episodes and thought they're very interesting, at least to me. I hope they're interesting to others as well.

Scott Langdon [00:02:31,550] I always find that too. It's a bit of a challenge, because I have always said, "I want to make a podcast that I want to listen to." So it's interesting for me to hear all of these things and mull them over. It's what I think about a lot. You know, who knows if the audience feels the same way? We hope they do. And that's why we bring what's on our minds, because every time we're working with these things, new ideas pop up — new questions, new thoughts. And so I'm always excited to talk to you.

Scott Langdon [00:02:59,630] I'd like to start this week talking about Episode 263 a little bit. That was From God to Jerry to You. And in this episode, you reference John D. Levinson's book, Creation and the Persistence of Evil, and you talk about it with Abigail in the intimate dialogue as well, which we'll get to shortly. But I wanted to talk about the From God to Jerry to You, because as I was looking at the transcripts and listening to the episode back again, there were a couple of things that popped out to me.

Scott Langdon [00:03:34,490] In this episode, you talk about John Levinson, and you encounter his book. And there are some things in the book that really coincide with what God has said to you, and you put six points together and you say, "God, is this — is John Levinson on the right track?" And God emphatically, pretty emphatically says, "Yes, yes," a couple of times. And you make these six points; you restate them. And one that popped out to me was what you call "the key point," probably the third: there is a negative or incomplete side to God. Now, you've been told something like that before. God has talked to you about being a developing, evolving God. When we get to Zoroaster, Zoroaster splits God into two opposing gods, a good God and a bad God. But that's not quite right, as God said. Not quite that. As your story, as you say here — I'm going to quote this transcript from the episode — "As the story unfolded in prayer, it became clear that God, who permeates the world, is not fully integrated."

Scott Langdon [00:04:44,830] Parts can come in conflict with each other. Levinson presents this as God trying to bring order to the world while the world continues to resist. This leads to the struggle of order versus chaos, good versus evil, occurring at every level of reality.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:05:05,520] Yeah, all the time. The shocking thing, almost, when you read Levinson as an Old Testament scholar, Hebrew Bible scholar, is that what he's doing is just telling you what he finds in that book, you know — that story of God and human beings interacting and so forth. And here God is so powerful, you know, creates the world and everything, and permeates everything in some sense, and yet evil persists. Evil persists. And this is always a puzzling thing. How can God let evil persist? And it turns out that Levinson's account fits exactly the unfolding story God had been telling me. "I'm an evolving God," and this made no sense to me, but that's what God said, so I wrote it down. It later kind of made a little more sense, but I didn't think it was present in the Judeo-Christian tradition at all. But here in Levinson, here it is.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:06:09,440] And then, from the quote you gave, Scott, it's not that God has an evil side, you know, like the way Zoroaster presented it. The two gods are really two aspects of the divine reality at war with one another. But no, it's something more like a lack of integration, as if you had an orchestra where the tuba is always playing too loud, the violins are sometimes off-key, and so forth.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:06:43,310] Parts aren't working, and I'm sure you, as an actor, Scott, must have — everyone must be aware that you can't let one actor sort of run away with it or hog the stage or be more prominent in a way they're not supposed to for the story that you're presenting on stage. And so it's a lot like that in our unruly world. These parts contend with each other, and they're all kind of parts of the total divine reality, after all. And the history turns out to be we and God, in our actions in the world, are trying to get it all together, you know, and that takes a long time, and we're partners in that effort.

Scott Langdon [00:07:30,720] Yeah, that's interesting. I've been thinking about this show that I just closed, A Christmas Story: The Musical, at the Walnut Street Theatre. We just closed last Sunday at the time of this recording here. You mentioned that an actor can't run away with a part. It was really interesting to watch the children — and by children, there are young people in the cast between the ages of nine and, you know, twelve or thirteen, I guess. And they play the kids in this story, A Christmas Story. If you're not familiar with the musical, it's based on the movie A Christmas Story that gets played every Christmas for twenty-four hours a day on TBS and TNT.

Scott Langdon [00:08:13,520] Kid's going to shoot his eye out with a BB gun, the whole thing. Child actors — it's interesting to watch them because we get something in rehearsal that works, and there's a funny line, and if they get a taste of a thousand people laughing at something that they said, it's very easy to stretch that out and milk that laugh. It can very well be. And it's difficult, even for the adults. I've been doing this for, you know, fifty years, and I understand that desire to lean into that. It's about me here.

Scott Langdon [00:08:56,590] It can very easily go from just right — catching that laugh, it's just delivered right, and boom, yes, it's just like it should be — to not working, just being forced. Oh, that wasn't — you know, it's just a fine, fine thing. And it has a lot — does it have everything to do, I don't know, with the ego, with this resistance part of it that God seems to be talking about? That there's this God wanting to have the world be in this way, and we resist it.

Scott Langdon [00:09:35,729] Levinson goes on a little bit here to talk about how one behaves. If one behaves rightly with your heart open to God, you are actualizing the ultimate fulfillment of the world in the present moment. Actually, I think those are your words — they're not Levinson's words — but you're commenting on what he's talking about. But the idea of behaving rightly, not obedient to a law per se because it's a law and we're supposed to, but because when you do what we've practiced in rehearsal, for example, for these children, and you understand the timing and the rightness of how your part should be played, and you play it rightly, you get the laugh and it works. But when you don't, quote-unquote, behave rightly with a heart that's not open to the whole story, but only your little bit, it just doesn't work. You know, there's something that doesn't click about it.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:10:33,870] Yeah, and so much of life is like that. There are parts that I think are law-like, you know — that's why we have the Ten Commandments. You shouldn't run around killing people, for example. But so much of life isn't at those extremes, you know, forbidden things — but they're subtle. And one of the hardest things in life is to be your right self, your best self, in any given situation.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:11:03,620] In relation to this person rather than that person, because interacting with Scott right now is different from interacting with my wife, Abigail, in our dialogues. We interact differently, and we pick up on each other differently. You and I, no doubt, are doing this interesting What’s on Our Mind discussion, interact a bit differently than we do at a planning meeting or something like that, and we're thinking, "What episodes are coming up?" and so forth.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:11:36,760] And maybe how to get the word out about them and that sort of strategizing. So we interact all these different ways. And I think ego is just one of the problems. There are others — fearfulness, you know, not wanting to go forward. It can be just elements of — or your emotions sometimes just run away on their own. This happens to people.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:12:04,140] The situation calls for some measured emotion, but you get too excited. For example, that might happen to some of these kid actors, and that's not just ego. But ego is one of the big factors — hogging the stage, what I call hogging the stage, you know, drawing all the light to yourself. And of course kids can probably just steal it, you know, because they have a built-in advantage there — a kind of enthusiasm and charm and so on. So yeah, that's all.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:12:35,960] I think the humor is a wonderful analogy, because I'm always struck that humor is so difficult. I don't understand it. I don't know how to be funny. Yet one always sees — you know — there was a guy named George Plimpton who, some years ago, tried — he played for the Detroit Lions — he was doing everything except being George Plimpton. And one was to be a stand-up comic. And so he gets stand-up comics to kind of train him and show him how to do it. Well — flop, flop, flop, flop. The only thing funny was watching the guy flop.

Scott Langdon [00:13:15,260] Right, right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:13:16,280] But these things are so subtle. But so much of life is. I've had this question a number of times — what to say to a person who, say, just lost a child. And it's very hard to know because it's so easy to say too much or too little, or to overstate your empathy, you know, as if you fully knew what that was like, or to understate it because you do have a good idea of what it's like. But there are a lot of these situations where how much should you say, or even situations where should you mention it at all?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:13:56,250] You know, they just got fired and fell on hard luck. Should you commiserate with them, or better to not mention that? Well, anyway, life, I think, is really hard this way, and you've got to mainly try to get yourself tuned in.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:14:13,550] To the situation, to the people in that situation, with some understanding of where you've been and what has happened and where you're going next. And that's part of what God is up to with us — is kind of helping us, interacting with us as a presence to us, and helping us — you might say — get our act together. But it's not a one-time thing. It's from one moment to another.

Scott Langdon [00:14:43,920] Hmm. One of the things Levinson helps point out is that he talks about the struggle and the relationship with God in two valid points of view. One is horizontally, where God and the world are moving in a disordered way, struggling toward a hoped-for victory.

Scott Langdon [00:15:05,590] So something we're always living in hope — we're always looking for, you know, the day when it all comes together and there's this movement toward something better. But then there's also this vertical way of looking at it, looking at all times at once, where God is fully good and victorious. From the vertical point of view, you say both the struggle and the victory are present now.

Scott Langdon [00:15:32,370] The events don't just move from earlier to later on the timeline, which Abigail talks about as something very valid and very strong and that we decidedly should look to, which is things moving along a timeline.

Scott Langdon [00:15:51,020] At the same time that this is happening — the word "time" is hard — but at the same time they can also be viewed vertically, in terms, you say, of what they point toward. And then I love this next bit where you say, "Every moment is like a flower turned toward the sun." Whether we notice it or not, the moments of our lives are turned toward the divine.

Scott Langdon [00:16:31,520] Now, that's really an interesting way to look at it. Horizontally, we're struggling to make the world better. We're wondering about, you know, left, right, politics, our president, all kinds of things about how to deal with the day-to-day.

Scott Langdon [00:16:48,110] But vertically, we're present to God, and the victory is already won. It's hard to get your mind around — get my mind around — those vertical and horizontal ways at the same time.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:16:48,110] Yeah, one challenge is they sound almost contradictory. You know, where does reality happen? It happens on the timeline. It happens in the world with one event after another. Two people have a fight — we always want to know who started it, who hit who first. You know, things like that matter. And as we try to improve our own role in the world and our own behavior vis-à-vis ourselves, that all happens on the timeline, and yet somehow every time has — you might say — its meaning. The meaning of those moments is in the vertical dimension.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:17:35,090] And the meaning of them is oriented to the divine. And just as the flower may or may not get to the sun — it might be a cloudy day, or some person built a wall, the flowers have to bend a different way and still may not catch it — okay, there are obstacles. Nevertheless, you might say the essential nature of things is much like that flower. We each are turned toward the divine by our very nature. It's the nature of what it is to be an ensouled creature, a creature with a mind and a soul and a spirit.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:18:50,500] That those are — just as your stomach gets hungry when your body needs food — this isn't ethereal that I'm talking about. Just as your stomach gets hungry, your whole self — and I don't want to separate out the mind, soul, spirit part — your whole self is inspired, after all. And its basic goal is toward the divine.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:18:50,500] So that's the vertical dimension, and the divine is accessible to it. It's right there, the way the sun is right there, shining. So that's the victory. And you can't have more of a victory than that. I mean, that's what victory is, you might say — is actualizing one's presence in relation to the divine and the divine's presence to you.

Scott Langdon [00:19:43,960] In Episode 265, that was Radically Personal 3. This is the third episode in our limited series, Radically Personal, that you're doing based on your book Radically Personal: God and Ourselves in the New Axial Age. And in this episode, you reference William James' book The Varieties of Religious Experience. And something that really impacted me is that James takes in the divine reality through a sensitive appreciation of its manifestations in human experience.

Scott Langdon [00:20:27,940] And it's not just — you say — when James speaks of experience, not just sensations or the sort of what Hume called impressions and others have called sense data, you say "little pictures that the mind collects and organizes." It's different. James, you say, is talking about lived experience — life lived by the whole embodied person embedded in a stubborn world, inheriting and sustaining human community.

Scott Langdon [00:21:17,260] And in one sense, if we just kind of backed up a little bit here to From God to Jerry to You, the very next part of that episode was you ask God, "What else should I know?" And God says, "Take a look at Jesus again in this light." And when we got to the Radically Personal episode, I still had that in mind.

Scott Langdon [00:21:17,260] And what I was thinking is God's — through Jesus — that's the experience, that's the lived experience that God is having in a way that — how does he put it? — "In Jesus, I am more fulfilled than anywhere else." And yet at the same time, God is ultimately the animating force of each one of us. So Jesus is very distinct in that way.

Scott Langdon [00:22:14,280] There's an experience in Jesus that's not going to be an experience anywhere else, in the same way that we are a unique experience that won't be experienced again any other way. The experience of Jesus seems to be more close to God than anything else. Could you talk some more about that part?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:22:14,280] Yeah, that too is puzzling, since God is, in some sense, you know, everything or in everything — permeates everything. And you — well, you've been saying this, Scott — that, well, what's so special then about Jesus again, you know? Well, we're all kind of — we all take in the divine and exemplify the divine and live it out in some respect. Jesus does that one hundred percent. And the way God puts it, more from God's side, is one formulation God said to me is, "I expressed myself in him." And just the way when you write a letter to someone or a love sonnet or something, you're expressing yourself — you're putting yourself into those words, right? Those aren't just marks on a page or something. You're putting yourself into those words when you talk on the phone, when you appear in the podcast.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:23:14,660] As we're doing now. We're putting ourselves into these words. We're presenting ourselves through these words, and that, in some sense, makes our thoughts and sentiments actual, you know, because we're able to actualize them verbally. And when we can see each other in person, that way — well, God is expressing himself, actualizing himself through Jesus, through that. And doing it, somewhat, with the rest of us, presumably, but way more with Jesus. It's as if Jesus is unfiltered. We've got a lot of distractions, a lot of things going on. Jesus — well, he occasionally has some other things going on, but on the whole, he is just taking it in, you know, you might say one hundred percent — just taking in the divine presence.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:24:07,520] Communicating it through him to the people he dealt with. And since he's a lingering reality, is what I get — he didn't die and leave. He's a lingering reality in the universe, still doing that.

Scott Langdon [00:24:24,530] The late Dr. Marcus J. Borg, a philosopher and writer who had a profound influence on me, particularly when it came to talking about Jesus — he wrote a book called Meeting Jesus Again for the First Time. That was the first book I read of his that really hit me hard and made me kind of think about Jesus differently. And one of the things — I don't know if it was him or if he was quoting someone — but I heard Marcus Borg say, "Jesus is what a life filled with God looks like."

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:25:01,140] Say that again.

Scott Langdon [00:25:02,410] Jesus is what a life filled with God looks like.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:25:07,039] Okay, yes.

Scott Langdon [00:25:08,140] And I thought that's — I've chewed on that for a while, for several years. And then, you know, we've talked about this a little bit before. It was a lens exercise some years ago where I decided that I was going to substitute the word "love" for the word "God" in my thoughts and prayers and talking about the divine. So instead of "God be with you," I would say "love be with you." You know — you understand.

Scott Langdon [00:26:10,820] And when that is coupled with Marcus Borg's statement — let's flip that word out — "Jesus is what a life filled with love looks like." And that even made it more deep for me. So if we're going to be like Jesus, you know — there were these wristbands that kids used to have at camp that had initials WWJD. The question was, "What would Jesus do?"

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:26:08,240] Okay.

Scott Langdon [00:26:10,820] A lot of good things about that. Some things that are troubling, but a lot of good things about that. But the idea would be, what would love do in this situation? And I've made it, in a sense, a very simple kind of math equation. Jesus is God, and God is love, then Jesus is love. And if we're to be like Jesus, we're to be like love. Now, how complicated does that get? So complicated that they might arrest you and hang you on a cross. I mean, it was a very politically dangerous thing to be that way then.

Scott Langdon [00:26:46,630] And now. And that's part of that struggle, isn't it? I mean, to be filled with God and then still be put to death for it is (Jerry: it can happen) what's the word that I'm looking for? It's subversive sometimes. I mean, what seems like power, what seems like being on top of the hill and winning it all in terms of life — that undercuts it. Jesus always undercut it.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:27:26,760] Yeah, it's a funny thing. It reminds me of the Grand Inquisitor scene, when the Grand Inquisitor, who represents the church — represents religion, Christianity — but has it in its earthly power form, you know, and Jesus comes along just being simple, as you put it — just sort of simple love — and gets denounced because the Grand Inquisitor, he's got the whole show on the road. And he's basically, "We don't need you." You know, we've got your figure on the cross, you know, all this stuff — rituals and music.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:28:06,400] Stained glass windows, and we've got the whole show going. We do not need you to show up. And it's been a long time since I read that, but Jesus, as I recall, doesn't really say anything. He just kind of smiles at him, in what I assume is kind of a loving way. And I don't know if anything happens then at the end — that's kind of where it seems to end. Maybe the Inquisitor walks off, shaking his head or something. But there is that peculiar moment, you know, and in a way I always wonder who wins the encounter.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:28:46,170] Well, in terms of power, the Grand Inquisitor wins. In terms of love, Jesus wins. So then it's a matter of, well, what kind of winning do you think is really important in life?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:29:00,720] And, well, many people will say, "Well, I go for power." You're just a — I don't know — you don't know which way is up or something. If you try to think you can go around just love, love, loving everybody, and you do have to watch it. You can't let — you can't give away everything you've got randomly, you know, out of quote love, a kind of unmoored love, a kind of ungrounded love.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:29:20,340] The life of love is also difficult. What is love? What is the loving behavior toward someone who's misbehaving, for example? You may need to slap them. I don't know, you know, or lock them up. My parents, early in their marriage — they were both high-spirited people, and they were both very young, both about nineteen.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:29:53,370] And my father reports that at some point my high-spirited mother wasn't getting her way on something and just started pounding him on the chest. Well, he thought, "I can't allow this to go on. This is violence." He just put her in the closet and locked the closet and then went for a walk to calm down himself.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:30:21,470] Well, he said he was kind of worried when he came back to unlock the closet. Now, is she just going to tear out? No — she walked out. She had thought twice about it — two or three times — in that closet and decided that she had not been behaving well. And so they remained high-spirited people, but very much in love.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:30:56,730] And that was, in that case, a loving act, because you're not going to have a good marriage if you let her do stuff like that all the time. Or it wouldn't be a good marriage if she let him do stuff like that. But he wasn't the one doing it. He was quite smitten with her. And they were married until her death, sixty-seven years later.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:31:53,820] And he said, "We were married for sixty-seven years, and it wasn't nearly long enough." But anyway, that's just one example of this concept of tough love. I sometimes hear people talking that way, and it sounds like more tough than love, but there is that tough-love necessity. And it's easy to not be tough in a loving relation, and that itself is a kind of ego — where you don't want to put yourself forward.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:32:25,530] Maybe the person you have to reprimand — my father had this problem with my mother — is she now going to turn on me? So parents have it with their kids. The kids are unruly — that's what it is to be a teenager — push the limits. And well, if you're going to be loving, you've got to put some limits. And they're practically begging you to do that. And yet it's often easier just to go along.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:31:53,820] So in every situation, this is very much like that example of humor. This is funny. A little more — it's not funny. A little strained — it's not funny. It has to somehow be clicking in the situation. And a lot of love, I think, is very subtle that way. What is the loving thing in this situation to do? And that takes some time.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:32:25,530] Actually, it takes some intelligence. You know, being loving isn't just a free flow like magma coming up out of a volcano. It takes some wisdom. There's a kind of loving wisdom. So you can do the right thing for a person out of love, and what's right for one person may not be the same thing that's right for the next person. So you've got to pay attention to those differences.

Scott Langdon [00:32:52,460] The word partnership — it comes up a lot. God talks about it, God being in partnership with us as humans. And human effort is essential to overcoming this incompleteness. What's being worked on by God is also being worked on by us in the actuality of — God can't mail a letter, kind of thing, right? The doing of it.

Scott Langdon [00:33:47,540] And so when I think of Jesus — if we could just go back to Jesus for a second — this idea of Jesus on earth as Jesus of Nazareth, son of Mary and Joseph, the carpenter, who becomes a preacher at thirty-three, all of that — those things — he had to have felt and known this duality that we all experience and said and understood, as you say, completely.

Scott Langdon [00:34:23,389] This partnership that God and Jesus are necessary in the experience of the physical Jesus to be in the world at just the right time. We are in the world, each of us, at just the right time. Right. So all of these things we are in partnership with God in — and also in partnership with Jesus in that way.

Scott Langdon [00:34:23,389] Jesus fully understands. I used to think — because the preaching was Jesus fully understands everything about me — and I'm like, Jesus doesn't know what it's like to be a father, to have children. No, he just doesn't. Don't try to tell me that he does, because he doesn't know what it's like to drive a car, to be going seventy miles an hour down a highway and be thinking about something else and go, "Oh, I need to concentrate on driving." That's not an experience that Jesus had.

Scott Langdon [00:35:04,680] At the same time, the part that is in partnership with God — the oneness with God — that example of what it means to be in partnership with God is something that is everlasting and something that we — we talk about Jesus lives in us. That's the part that we can work with in partnering with God.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:35:04,680] Yeah, and the Jesus of the Gospels is giving us a tutorial in what it's like to be loving as we see him handle one situation after another. You know, he's arguing with the people in the synagogues when he's really too young, but he understands it in a way they don't. And we all know that there are people who get book learning and they can spout off the lines they've learned, but they don't really get it.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:35:56,820] And you experience that. You've taught literature to students. You experience that — the student who's read the Wikipedia or something and can say the lines, but has no idea what's motivating Macbeth or some character that is in something you're teaching. And Jesus gives us that example.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:35:56,820] Of in all these different kinds of cases. And like all of these things where you're learning — and since Jesus is a present reality, you can connect with Jesus. I mean, I was asked, should I pray to Jesus or to God? And I was told either one. If you pray to Jesus, it will go right to God.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:36:32,650] You know, there's no further step, as though you've mailed it to the regional postal office but you've got to go somewhere else to be distributed. No. You can — or you can pray directly to God. You don't have to pray, quote, "in his name." That's a perfectly good thing to do, but it's not required.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:36:47,760] You can pray directly to God, and God's happy to answer. And I think even cites — I can't remember this exactly; it's me citing it in this context — Krishna, in the Hindu tradition, says any prayer sincerely uttered comes to me.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:37:16,940] Well, I think maybe it's more precise in that tradition, since they also, in a sense, have multiple gods in the full mythology, you might say. It'll go to the God that needs to hear it, you know? And so you don't have to worry that much. If it's a sincere prayer, divinely directed, you're home free.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:37:41,480] And Jesus is right there. And if you're a Hindu, that's fine too. And whoever prays — at least if you take that seriously — but it seems very much in the spirit of Jesus to me, you know. "Suffer the little children to come unto me." Everybody's welcome. You don't have to qualify in some way.

Scott Langdon [00:37:41,480] I have always been struck by "If you seek me, you will find. If you knock, the door will be opened.” That's a call. So it goes to that sincere inquiry — the sincere desire to partner up with God in that way. "What is your will for me? What do you want me to do?" And it comes to you.

Scott Langdon [00:38:59,320] There is never a thing that you've been through that you haven't come through. Here we are — of all the things we've gone through — and here we are. And it's always fascinating to remember — to re-remember — that God is not only desiring to partner with us, but that's what it is. That's what the duality in our world is about — partnering with God to find a way.

Scott Langdon [00:38:59,320] Otherwise, we do feel lost and alone, and we can feel that way. And when we remember that those are thoughts that come and go, but that which is animating us — the animating source of us, as I've mentioned before — we can partner with that.

Scott Langdon [00:39:25,460] And Jesus goes right on and says, "I and my Father are one." I know that. And so what can I fear? Even though he has drops of sweat that are like blood in the Garden of Gethsemane saying, "You know, is there a way that I can get out of this heat?" He knows that God is right there.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:39:25,460] Yeah. That knock — knock, and you will find — just seems so profound. It's almost the essence of the whole thing. That reminds me again of the flowers turning toward the sun. The sun is there. You know, all the flower needs to do is turn toward the sun, and that's the sense also, that vertical dimension then. It's the sense in which, as long as we're seeking — and seeking here is shorthand for turning our souls Godward, you know, kind of opening ourselves — to let the divine sunshine in, you might say. And if we do that — obviously sincerely; you're not doing it unless you do it sincerely — then you're not pretending to turn toward the sun. You're not pretending to have an open soul, to want to live a divinely guided life. But if you really are, God is right there with you in partnership. And that's the kingdom of God. I think, in the end, that's the kingdom of God — which is not something to wait for, but you have it right now, as soon as you turn your soul toward God.

Scott Langdon [ 00:41:09,380 ] Thank you for listening to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. Subscribe for free today wherever you listen to your podcasts and hear a new episode every week. You can hear the complete dramatic adaptation of God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin by beginning with Episode 1 of our podcast and listening through its conclusion with Episode 44. You can read the original true story in the book from which this podcast is adapted — God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher — available now at amazon.com, and always at godanautobiography.com. Pick up your own copy today. If you have any questions about this or any other episode, please email us at questions@godanautobiography.com, and experience the world from God’s perspective — as it was told to a philosopher. This is Scott Langdon. I’ll see you next time.