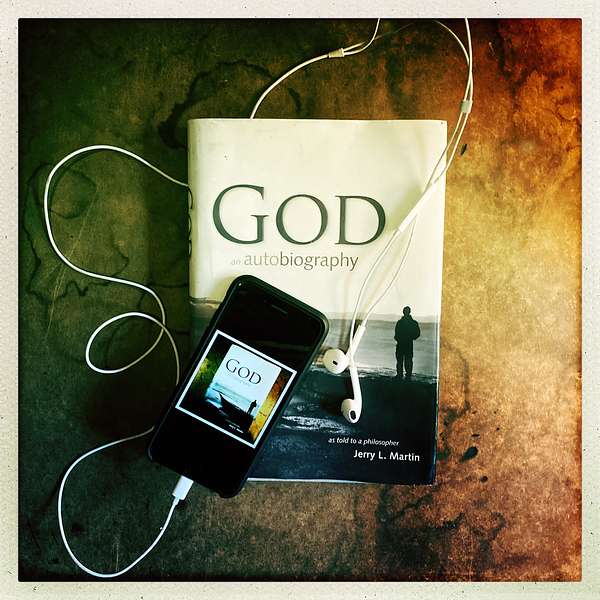

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

89. What’s On Your Mind- A Relationship With God

Hear profound communications from readers responding to God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher, inspired by the pivotal moment of faith when Jerry, a philosopher, and nonbeliever, sends prayers of gratitude to the unknown. Meet Gerald and Margaret, who share contrasting experiences and obstacles in their relationship with God.

Gerald is a skeptic, dismissive of divine relation, yet open-minded enough to be a seeker of truth. Margaret can connect with God in simple yet profound ways but struggles with the relatable issue of willfulness getting in the way of purpose.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin, author of the true story and recorded communication with God in God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher, and show host Scott Langdon, discuss these two letters of spiritual blocks, lessons on life, and forming a purposeful relationship with God- getting to the heart of God's reported message.

If not through the mind, how does God communicate with humans? Open the mind- listen with intellect and heart as this discussion journeys to the existential edge of life. These lessons go beyond philosophy, Hegel, and Buber, and resonate with the same profound wisdom hidden in tales like The Little Prince and preserved in the purposeful willfulness of one of history's greatest treasures, Joan of Arc.

Would You Like To Share Your Experience With God? We Want To Hear About Your Spiritual Journey!

Read God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher.

Begin the dramatic adaptation of God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher

Related Episodes: [What's On Your Mind] Trusting God; Is God Hiding?; Seeing With Divine Eyes; Mindful Moments; God's Frequency; Spiritual Living; A Relationship With God; Spiritual Judgment

Share Your Story | Site | Facebook | Instagram | Twitter | YouTube

Scott Langdon [00:00:17] This is God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. A dramatic adaptation and continuing discussion of the book God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin. He was a lifelong agnostic, but one day he had an occasion to pray. To his vast surprise, God answered- in words. Being a philosopher, he had a lot of questions, and God had a lot to tell him. Episode 89 Welcome to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast.

Scott Langdon [00:01:05] I'm Scott Langdon and this is the eighth edition of our series, What's On Your Mind? In today's episode, Jerry and I discuss two new emails sent to us here at the podcast, the authors of which give their own unique take on what it means to experience God, or not. While reading through these emails, several questions came to the foreground. What are some of the obstacles to being in communion with God? What might they look like in daily life? Is there natural evidence to support unbelief? What might that evidence be? And when it comes to our will being an obstacle to face, what can we do? Jerry and I break these questions down and try to get to the heart of God's message for our daily lives. Thanks for spending this time with us. I hope you enjoy the episode.

Scott Langdon [00:02:01] Well, welcome back, my friends. We are glad to have you for another edition of What's On Your Minds. And today, Jerry, we have two really interesting emails that I think have made me do some really deep thinking in a way that I haven't done in a couple of weeks on these. These are pretty poignant and wonderful emails. I'm glad that they wrote in.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:02:22] Yes, I felt the same way, Scott. They raise very interesting issues and they're, to my mind, more complicated than they might appear at first glance, that they're raising a number of issues that need attention and teaching us some lessons along the way.

Scott Langdon [00:02:41] Yes. As we went back and forth preparing for this episode, the word that came up is- obstacle.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:02:48] Yes.

Scott Langdon [00:02:49] That there are significant obstacles that keep us, seem to keep us, from communing with the divine in the way that we might be able to- that God might want us to be able to, and these obstacles show up in a lot of different ways. And these two emails sort of-- they're not opposites, but they do seem to go on either side of the spectrum. And it seems to be a decision that one makes on what kind of life one wants to live, how one wants to see things.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:03:22] Well, a big difference between the two is, I think the first one we'll be discussing is Gerald, basically doesn't want to go down that track of talking to God and trying to listen to God. And he gives reasons. He's not just, you know, refusing to listen. And Margaret does go down that track of connecting with the divine, but then runs into obstacles of her own along the way, and so that's very interesting.

Scott Langdon [00:03:56] Yeah. So, let's get into these emails. We're going to start with Gerald, and Gerald wrote into us and I'm so glad that he did. We have an invitation every week that if you have a story or an experience of the divine and you have a question or comment that we'd love for you to email us at questions@godanautobiography.com. And Gerald writes in with a point of view, and here's what Gerald says: “Two different people can view the same event and come to different conclusions, obviously. If one is predisposed to believe that there is a god of some sort, then he can view the event as one caused by God. despite any evidence to the contrary, despite the natural evidence. There can be no god and that doesn’t make any difference. One can “hear the voices” and nothing is there, but in that person’s mind.”

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:04:56] Now, that's a fascinating comment from Gerald. And I imagine there are many Geralds out there, you know, going through rather similar thought processes about what to make of this. Someone says, I talk to God, and he's saying, yeah, people can think they're talking to God and nothing's going on. And well, anyway, here's what I wrote at the time, “Thanks for your comment, Gerald. If I had not had the experience, I might say something similar, but probably would not have. I was an agnostic; you sound like an atheist. It had never dawned on me that, even if there were a God, it would be the sort of God who could speak to me personally. But I was also an empiricist — theories must fit experience, not the other way around. Obviously, one can hear a voice, when nothing is there, but sometimes there is something there and you just sort of know it, the way you can usually tell whether you are awake or not, or whether you remembered something or just imagined it. Trust your experiences too much and you can be gullible; trust them too little and you can miss what life is really about.” And does that make sense to you, Scott?

Scott Langdon [00:06:30] It does. It does. And when I was preparing for this conversation today, I went back and actually in part, one of the things I did was I listened to an early episode of our podcast, which is the adaptation of the book, and in it was the section where you talk about having read William James, The Will to Believe. And you kind of-- what you came to there was in James's idea that there are certain ways that if you believe them, will, you know, if you go down this path, it will change your life entirely or not, you know, and you decide if you do or not. Now, I find it interesting that Gerald took the time to sit down, either take out his phone or get to the computer and write this out. Well, why take the time to write about it and make an argument for it. Now, there's nothing wrong with being an atheist, if that's, you know. It just was interesting that it seemed as though there was a decision to say, here is my argument.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:07:37] Yeah, that's a good point, Scott, that he did care enough about the issue. A lot of people, they just dismiss something. It's like the Loch Ness monster or something they never even second thought. And so, it might be not quite right, my guess is that he's an atheist because he's kind of negative, but he might be a certain kind of like a skeptical agnostic, you might say, someone who doesn't want to believe something that isn't so, which is extremely important- to believe things that are so, and not to believe things that are not so. The point of my final comment to him was you don't want to be gullible. On the other hand, trust your experience too little and you can miss what life is really about, you know. And Margaret, she'll be kind of talking about that also, and a lot of people we've been hearing from talk about that. Wow, you know, this is the centerpiece of my life, it's giving me my compass, you know, sense of purpose, what I'm supposed to be doing. I know I am more integrated. I've got my act together. Richard Oxenberg and the dialogues sometimes talk about that. But your point is a good one that Gerald is stating his reasons. And I would just like to let him know. Well, yeah, you can be mistaken if you think there's a voice, and you can be-- you can lose out if you don't credit anything that comes your way. And I've certainly known people like that, that they kind of have a little frame of beliefs, maybe they're based on science or some kind of conventional secularism, and they just don't look at anything else. Their minds are not open. Well, I think you're right, Scott. Gerald's mind is a bit open and good for Gerald. He says the person predisposed to believe in God is going to think it's God. Well, that's true. That's true of all of our lives that we tend to believe things that fit our beliefs more readily, unless evidence, you might say, when things that don't fit our beliefs, and then we ask for high stacks of proof if it's going to go against our beliefs. And that's, what do they, there's a word for that, confirmation bias in research projects. But and I notice he says, the person predisposed to believe in God can believe Him despite any evidence to the contrary. Despite the natural evidence. And what strikes me about that is, well, what evidence does he have in mind? Right?

Scott Langdon [00:10:20] That's what I was thinking, too. Yeah, yeah. What would that evidence be?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:10:24] Yeah, yeah, yeah. There is no other evidence I had the experience I had, and reported, and if he had had the experience, he would have had it and reported it. and there was no contrary evidence. Contrary evidence, as I've tried to think this through would be, oh, if you find I'm on drugs or in general a Looney Tunes character, then you think, well, you can't trust that guy's reports. But, you know, and I checked myself out, you know, if I'm a Looney Tunes character. And then I was again struck about that one can hear the voice, he says, and nothing is there but in that person's mind. Well, maybe, you know, God can speak to you in your mind. You know, God's a spiritual being. You might say we're spiritual beings and spirits can communicate with one another. And I sometimes say, who knows what the physics of divine voices is. You know, I wonder, could you have tape recordings? When I heard it audibly out loud, I looked at Abigail. She did not respond, so she obviously did not hear the voice I could have said- Ah. That's just confirmation. Maybe that would be the kind of thing Gerald would have in mind is just confirmation. But I thought, oh, this voice is just for me. So, that's just a different-- and that seemed to kind of fit the experience to think of it that way. So, one has to, and this is William James point, okay. God comes to you however God comes to you, and it's up to you whether to credit it. And for him, an awful lot depends on, well, what kind of life do I want to live? If I'm going to live a Looney Tunes life, then that's no good. But if I'm going to live a richer, more unified, more purposeful, more integrated life, that's a good thing. And one other thought I had, Scott, maybe, you know, the play of, you know, he says nothing but in that person's mind. In George Bernard Shaw's play, Saint Joan, there's a kind of inquisitor type- prosecutor. He's the prosecutor, and he says, Joan, he keeps hounding her this way, "these voices are only in your imagination." And she says, "of course, that's how God talks to me." Why throw out imagination? I mean, there's fancy, you know, where you imagine winged horses and so forth. But the human person has a lot of capacities and some of them do have to do with tuning in spiritually, capacities of imagination that are ways of apprehending truths or the meanings of things. So anyway, I thought, yeah, Joan, you know, that's not a bad answer.

Scott Langdon [00:13:39] Well, I was thinking in terms of, you know, evidence, and knowing, and such, and we've talked about this a little bit before, but just the idea as we record this right now, I am in lower Delaware. I'm in Millsboro, Delaware. And you're in Doylestown.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:13:56] Yes.

Scott Langdon [00:13:56] And I'm looking at my computer, I'm looking at a screen machine. I'm talking into this little device, and I have these things in my ear, and I believe that I'm talking to you. I know that you and I are having a conversation.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:14:15] Yes.

Scott Langdon [00:14:15] And I know that it's real.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:14:17] Yes.

Scott Langdon [00:14:17] But that's so silly. Can you imagine somebody-- well, can you imagine Joan of Arc coming through time and being here in the room with me now? What are you doing? Who are you talking to? Everyone thought I was crazy and decided to burn me because I was talking to somebody just like you are.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:14:32] Yeah.

Scott Langdon [00:14:32] Well, yes, Joan, but I know that Jerry is there. And she would say, "Yeah, but I knew God was there."

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:14:40] Yeah.

Scott Langdon [00:14:40] You've mentioned that in the book. You know, it's like God's voice from outside, but it was just as if my wife were talking to me. There's a knowing there.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:14:49] Yeah, it was completely ordinary in that sense. So, I never quite relate to those accounts of religious experiences where people freak out, collapse on the floor. Some of those are biblical, in fact. You know, yikes, what's happening!

Scott Langdon [00:15:05] Right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:15:05] I'm a bit more like Moses when there's the burning bush, says Moses turned to look.

Scott Langdon [00:15:15] Yeah. What was that?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:15:16] Burning, but not consumed. So, what's going on here? Now, he could have rushed on, or said that doesn't make sense, you can't have it burning and not consumed. It must be an optical illusion. He could have dismissed it as nothing's easier to do, you know.

Scott Langdon [00:15:32] Right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:15:32] But he stopped. And only when he stopped and paid attention did the voice from the fire speak.

Scott Langdon [00:15:42] Yes.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:15:43] So that's one of the lessons in life is you've got to give some credit to your experience. Now, I was not like the guy that Gerald is arguing against. I was not someone who already believed in God and therefore more credulous with regard to the divine voice. I had prayed, but my prayers were to a God I didn't believe in. And I say that in God: An Autobiography. The fact that I felt gratitude for the love that had come into my life and I'm a philosopher, that doesn't change the structure of reality. That's just my feeling of gratitude. Nevertheless, I certainly felt it and it was an authentic feeling. And so, I thought, well, then let's express it. Why not? And it was about the third prayer or something that where I, without expecting any answers, because I still do not believe in God, but I asked for guidance and God spoke up. Well, you know, every story is different.

Scott Langdon [00:17:28] It can get tricky a little bit sometimes. I think what you experienced was, you know, you were an agnostic, didn't believe, you know, necessarily if there's a God great, if not, it's fine- didn't really think much about it. But this desire to express gratitude beyond yourself, even if you don't want to say to a God or, you know, you expressed it to a God I didn't believe in. But just to something beyond me. There's me and then there's something else, and naturally, in a natural way, because of what's come into my life, I feel like I want to express this gratitude. And I think that that is-- I think that happens in human beings a lot. And to Gerald's point, when you are raised in a certain tradition, one in which the talking points are often if you ask God for something, God will respond God, you know, that's baked into the idea of your religion. And so, if you have a desire either to express something or cry out for something, or you're going through a difficult time, and you cry out, and you feel like you hear no answer, that perhaps can be the natural evidence of- look, I've tried it. I've said, God, where are you? And I've got nothing. That's the natural evidence. That's how it is in the world, and everybody else who has these experiences are making them up in their minds. That's, that's-- I can see that point of view. At the same time, I think to go back to the starting point, which is where does this natural desire to express or to cry out or to where does that come from? It to me., I feel it comes from within. So, if I'm looking for a place to without, outside to find a place, you know, who is, where is it, where's this experience? But I know that you've talked before that you know, there's, God from within, but then there's also God, you know, outside. And you see a God having an answer in the wind or in someone else talking or whatever, being open to it, to whatever it is. But my point is, it's all going to come through your mind. I mean, that's who we are. That's how the process, you put gas in a gas tank to make-- you know, that's what a gas tank does. The mind is what-- where, we often say filters things, but it's not really even a filter. It's a-- that's the mechanism through which experience is experienced, through the mind.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:20:10] Yeah. That's true even of experience of the physical world. Right?

Scott Langdon [00:20:13] Right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:20:15] You experience it with your eyes, and with your ears, and by walking around and feeling, you know, the gravity pulling you to the earth and so on, you know, the weight of your body. All of that is experienced and it's always possible. You know, the big- in philosophy, there's a big skeptical tradition because people are always bringing up- oh, but that could be wrong, that could be wrong. Okay, well we know this or that experience can be wrong. But it's kind of bizarre if you think it's all wrong.

Scott Langdon [00:20:44] Yeah, because there could never-- Could it also be right?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:20:47] Yeah. And it could also be right. And you might learn something by trusting experience. You're not going to learn much by distrusting it, by throwing it in the ash can.

Scott Langdon [00:21:01] Absolutely. And I can say just from working on this project, and we've talked about this a little bit before that when we started, I needed the job. But here is a guy who God talked to him, and he thinks he talked to God, and, but I need this job. Then it got to a point where I thought, I can't do this for the money. I either have to-- So I shifted my thinking, and I asked the question to myself, which was, what if it's true? What if he really did have this experience? Now, I don't have to believe that or not, because I didn't have your experience. You had it. So, we're just going on that and it really doesn't have anything to do with me, whether you had it or not. But if I play with the idea that you haven't, then I really can't learn anything because I've already closed off my mind about it. And so, it would have been a job for money for a while, and then it just would have fizzled out because that's not, that's just not the way of God. It just would have gone on. Somebody else would have come on, you would have done something else, perhaps. But when I ask myself that question, and as an actor, and as an artist, I thought- all right, well, this all right, let's see. What if it could be true? Then now what? Because when I say it's not, then that just was blah. That's not interesting. But the possibility of it being true is interesting. And so, I surrendered to that and went with it. And my life has completely changed as a result because not because you had the experience, but because when I trusted and opened and let it go, there are still some things that I find skeptical about your experience. I go, really? You know, but that's not about me. Now, I go- well, what's my experience in light of this? And then I look at my experience more deeply that was provoked or brought on or pushed ahead by your experience and my association with your experience. But now I'm into my experience and I think deeply about where was God talking to me here? Oh, that's interesting. Maybe God was pointing this out and look where you are now in your life at more of a peaceful place. Doesn't that feel better than not having a peaceful place?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:23:17] Yes, yes. Yes. No. It's like- anything like atonal music or a strange cuisine or, you know, or a new kind of exercise procedure. Well, unless it's going to do you harm, you're going to learn more by checking it out than by dismissing it. Oh, I can't stand that, you know, in advance. So, you take things in with a bit of an open mind. And on those things, one can't believe there are things in the book that I find embarrassing. But my job isn't to be the censor of what I'm told. It's to report what I'm told. And what I generally advise readers is if you find parts that do not speak to you. Ignore them.

Scott Langdon [00:24:07] Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:24:07] Read on and find the parts that do speak to you. Because I guess my own belief about God: An Autobiography is that it kind of has a message for every reader. And it's not exactly going to be the same message for this reader, you know, for Scott, as for Ann, or Margaret, or, you know, Jane, or Gerald, if he reads, you know, sticks with it. You take what you do take from it and make the best thing you can of that.

Scott Langdon [00:24:39] Yeah. Yeah. And I think your last line in your comment to Gerald, "Trust your experiences too much and you can be gullible, trust them too little, and you can miss what life is really about."

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:24:51] You miss the whole thing.

Scott Langdon [00:24:53] Yeah. The central point, I think, is to pay attention to your experiences. Pay attention to them. I get caught up a lot in projecting on what's going to happen. A lot of thoughts about what are going to happen and a lot of thoughts about what did happen. And I wish I could go back and did it-- When I get caught in that part, I realize that I have taken up time and given energy to something that is not real. Something in the past, something in the future, those things are not real anymore. You know, it's my projections of them. The experience that I'm having when I note the experience, and I just- where am I in the experience, here? It seems like that is when I can get the most clarity when I'm, you know, trusting and paying attention to my experiences. Now, when you've had an experience, and in a sense, you are looking back, you're going, okay, just had that experience, but you're doing it from the present moment and you're evaluating it from now. And in that sense, where I found I've been in communion with God is in those reflective places asking God to come into communion with me, saying, God, this is something I want to go over together. I'd like to look at this experience I just had with my wife or with my mom or something. And when we reflect on it, I think that God and I are reflecting on it together, that it's not me having thoughts about the past- oh, I did this, or that. I go, God, what was that, like, where are we?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:26:25] Yeah, in the intimacy of the divine presence, that funny sense in which God is you, and me, and everything, comes in handy here. It's a very intimate relationship, right? Because it's also what makes us up. You know, it's all the stuff of our being is divine. It's divine stuff. And so, God is both inside and outside. And that inside means you're thinking. I have sometimes been told that some of the thinking is really God put there. Where I'm asking God, are you telling me this? Or did I lapse into my own thinking? The answer was, sometimes what seems like your own thinking is really me, you know, it's God kind of thinking through me. Okay. And then you're talking about doing that in a kind of partnership mode, as you reflect on an experience. What's the meaning of this experience? What does it mean to me? What's my takeaway, you might say.

Scott Langdon [00:27:25] Yeah, and I don't expect because it hasn't been my experience, it might be in the future, I don't know. But it has not been my experience to hear a voice from the outside in the way that you did. At the same time, as we talked about earlier, there is a knowing. That it is the same kind of knowing that we're doing right now where you're in Doylestown, Pennsylvania, and I'm in Millsboro, Delaware. And yet I believe we are presently communicating when you say something to me and- Oh, yes, I hear that. That knowing it's the same knowing even if, you know, said, well, God's not there and you know, I don't hear your voice and there is no God, and it makes no difference. Well, when I go evaluate a difficult experience, say, and I know I'm doing it by myself, there's a different feeling than when I go, God, my mom is ill. And there's a lot of confusing feelings about that. And I'm sad and I'm, you know, can I be happy sometimes, or should I-- you, all those feelings, and I just get this knowing that everything is just fine.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:28:32] Good.

Scott Langdon [00:28:32] It's a knowing.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:28:34] Yeah. People almost worry too much, and that actually relates to something Margaret says, because she describes an experience that is, she calls it simplistic. You know that it's so simple that you don't need to figure it all out and it would reflect your attitude, Scott, I think what you just said, that everything is okay. You know, when you're in that- in relation to the divine, and properly in relation to yourself, because that has some great resemblance to being in proper relation to the divine, then everything's okay. Everything is okay. Even though that doesn't mean there won't be suffering. That's a whole different question. Whether you stepped on your-- a sharp object or something, you know got sick. That's a whole different question. But the question is usually about, you might say, the state of your soul. You know, how is Scott the person? Scott, the flow of experience. Scott, the consciousness. And well, basically, if God is present, which God always is, but you don't always notice it, if God is present. Then Scott is okay.

Scott Langdon [00:30:35] Let's get to Margaret's e-mail, because this is a beautiful one, a fascinating one, and I'm so glad she wrote in. So, if Margaret, if you're listening, this is a great one. She says this, she says: “Jerry- This excerpt has been on my mind all day. God told me something similar a few months back. I found that when I let him in, I felt happier in a simplistic sort of way, as if there were nothing to figure out but to simply be in his presence and that was well enough. The more I listened (listening not with the mind but through the heart), the more I felt this light guiding me from above, I could literally feel him so softly above me, more like a light shining down, a hand at the top of that light. My choices through God were healthy, I was still me but more fully me, more whole. Then there is my will, I know when I choose to ignore the holy presence, this is where it gets tricky. It's as though someone spins me around in a chair, the world opens up and the backlash is quite unpleasant, so many ways of being, none involving his full presence in me. So, each time I fall, it gets a little clearer than the time before (can also be a little more painful) but I am learning so much and am so blessed to have this life experience. What God has in store for us is truly amazing. Thank you for listening to God’s voice.”

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:32:10] Yeah. Isn't that an amazing communication to us? I'm so grateful to Margaret to share that experience and those thoughts. They're profound and at the existential edge of life.

Scott Langdon [00:32:25] Mm hmm. Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:32:26] And deeply meaningful. My comment, and I often make this kind of comment because I think people do want things to extreme when they're looking for a spiritual experience, a religious experience.

Scott Langdon [00:32:43] Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:32:43] And so I, in fact, say to Margaret, “People often want God to do something for them or give them breath-stopping experiences, but the most extraordinary thing is what you report — the way in which the divine presence is itself enough, more than enough even, more than we may easily be able to take in. But days lived fully with God are good days, and days lived only in the presence and in the service of our own wills, are bleak, even desperate, by comparison.” So, she's taught us a real lesson there, hasn't she?

Scott Langdon [00:33:29] Yeah. Yeah, I think so.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:33:32] And, I mean, I was so struck by the way she describes at the beginning, if we go back to the first couple of sentences, "when I left Him in, let God in, I felt happier," and here's where she uses that word simplistic, "in a simplistic sort of way." As if there were nothing to figure out but to simply be in His presence. And that was well enough. I mean, I'm struck, you know, I'm a philosopher. We're always trying to figure things out, an awful lot of God: An Autobiography is I'm trying to figure things out. And I'm asking God, you know, as a logic professor, sometimes I'm saying, oh, that doesn't make sense or something like that.

Scott Langdon [00:34:17] Right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:34:18] But Margaret has a kind of wisdom here that based on her experience- oh, just I don't have to figure out anything, just to simply be. And it is simple. She's stressing to be in the divine presence, that is well enough. The more I listen-- listening, she says, not with the mind, but through the heart. You know, we kind of forget, you know, again, I'm a philosopher, I've always been a logician trying to figure everything out, as if we're trying to come up with a theory of God, like the quantum mechanics of God or something. But she's on the right track. I want to listen not with that intellect aspect, but through the heart. Just take it in, through the heart. The more I felt this light guiding and so forth, that's what worked for her. And then the choices for God were healthy and I was more fully me and more whole. So that's the healing experience. And again, she's reporting her experience there. She's not deducing this from some theology or philosophy or something, a minister, or a guru or someone told her, you know, this is her experience.

Scott Langdon [00:35:32] I really like Margaret's take on the idea of just being.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:35:38] Yes.

Scott Langdon [00:35:39] Just being. And when I think about how to sort of notice that experience, I think about how God and I lately especially have been exploring what is-- what are, what are my thoughts and my feelings and my perceptions and all of them, real in in this world there are, you know, suffering and joy, and having all of those things, but they're all temporary. Sadness will go away. A happy feeling, a magical moment, they all come and go. So, none of those things that happened to me, none of those things that happened during the experience are me, because they come and go and I'm still here, you know. And so, when I feel like I'm in communion with God, the grace for me, grace is the built in that's available for everyone. There's this built-in notion that when God says, "Be in tune with me." Part of what that is recognizing that none of the thoughts, feelings, perceptions, emotions that just seem to be everything in your world, none of them are permanent. We hear them talked about in the New Age talk. They're not real. It's not real. Well, it's real because it's your life and that's your experience, but it's not you. So, when I get that piece of, okay, this will all work out. This will all-- And you just know, because you get to that place, as Margaret said, of just being and I'm being with God. I feel like God is saying the grace is the recognition, the reminder that none of this is you. Does that make sense?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:37:27] That's a wonderful way to put it, Scott. That is in a way, a matter of definition. Those things do not define you. The presence of God sort of does.

Scott Langdon [00:37:36] It kind of does. Right? Yeah, yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:37:38] Yeah, yeah. Because the point is, it's intimate and up close and kind of in the heart of your being, you know, the being of your being, there is the divine. And, whereas those other things aren't the defining elements of Scott, they're experiences that you're passionate about in life. Yeah, but they're not the defining element. That term, so I, you know, I really liked Margaret's talking about simplistic, and I think that kind of connection that made in my mind as I not too long ago read the little, I guess you'd call it the fable? The Little Prince.

Scott Langdon [00:38:23] Hmm.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:38:24] Have you ever read that?

Scott Langdon [00:38:24] Yeah, yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:38:25] But it's a child's book, but I think it could be criticized for being simple and sentimental. Simplistic and sentimental, but I think it's profound and wise. And in the case of that little book, it's a very short book. The kind of simplicity and sentiment are the instruments of its profundity and wisdom. It's through that simplicity and, you know, kind of earnest sense of feelings. That's the sentimentality, just recognizing what the feeling is, like when you love someone, and he has a relation to a fox or something. But anyway, and he notices, oh, the world changes when you have a friend. The world changes. And that's very simple insight. You'd call it sentimental, sounds like a Hallmark card. You know, dear friend, the world changed by meeting you. But it's extremely true, and that's why somebody like a great thinker, like Martin Buber, could write a book called I Am Thou. You know, the heart of, one heart of human life is the relation to other people and the eye to the Thou, the person we address, and as he says, the beginning of one section- The I, thou relation stretches to the eternal Tho, it has a natural trajectory to the divine. If lived out properly and understood properly, so anyway, these simple things are underrated and these complex things are overrated. People think, Whoa, some big, complex things. Six big charts to lay out a spiritual vision or something or other, some philosophy. I remember something on Hegel where you unfold a whole long chart that shows all the stages of the dialectic. Whoa. Well, Hegel is impressive. However, I don't know that that's truer than what Margaret is saying here. You know, this is about as true as you can get. The will intervenes. And when the will, she doesn't quite define that, we have to figure out what does she mean by will exactly? Well, I think a bit in the sense of willfulness.

Scott Langdon [00:40:53] Yeah. Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:40:55] When I choose to ignore the holy presence. Whoa! She says it gets tricky. It's worse than tricky.

Scott Langdon [00:41:02] Hmm. Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:41:04] And I puzzled around, I puzzled over, she says- when willfulness intervenes, you were in the presence of the divine. And that peace, you might say, with God in yourself. It's as if somebody spins around a chair. I guess it makes you dizzy, huh? I mean, I puzzled about that image. And what finally struck me was you could think of it as, of course, your body is in part your compass, but it's like somebody messed up your compass. Then it's going to fly in every direction. You're not going to know where true North is.

Scott Langdon [00:41:43] Right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:41:43] And you're badly oriented. That's the experience we all seemed to like when we were kids. So, getting the world around them and then, whoa, you don't know which way is up anymore, but you lose your orientation. And in this case, the orientation to what's most important in life.

Scott Langdon [00:42:03] Mm hmm.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:42:04] So willfulness is the thing to watch out for. And it's also good and simple until you get willful. All right.

Scott Langdon [00:42:14] You know, like one of those moving sidewalks in an airport, you know, and you're just going down this way. Well, you can turn around and walk against it, but why would you do that? And I think when she says, you know, my will, it's sort of I'm going to turn around and walk against the flow of the sidewalk here. It can be painful. You fall down, you get knocked into other people, you know, you whatever, and you get disoriented. Like she says, you spin around, where is the direction? When we talk about, you know, walking out a second-floor window, stepping outside, you're going to fall. And God has talked about that. God talked about that to you in terms of that God is the organizing source, the organization of the patterns of the universe, that there is a gravity, that there is, you know, those are the laws of the world being in the world, and God is them created them and is beyond them at the same, you know, all of that. But we also have the gift of having the ability to turn upstream. We can do that to explore. That's the experience. But then we go back to what we're talking about today, which is when you have these experiences, can you observe them, look at them and say, that was me being willful? I could, you know, you just feel there's something wrong if I want to lash out at this person, curse at them, or...

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:43:40] You just kind of know it's wrong.

Scott Langdon [00:43:41] You just kind of know, you know, because you're against that flow of the river, you're against the will. If we want to talk about it in Christian terms, Jesus says not my will, but thy will be done when he's in the Garden of Gethsemane, about to be arrested and taken to the cross, you know, and that idea that Jesus would say, I have a will, but not mine, but your will, God's-- the will of the way of God.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:44:08] Yes, that's a good point. Even Jesus could be willful if he made that decision, and it's not beyond his capacity to be willful, and certainly the rest of us. And yet, you know, it's not the right direction to go. There's a Chinese blessing, I guess, well-wishing. May you always ride in the direction the horse is going. And that's pretty good. That is pretty good.

Scott Langdon [00:44:39] That is wonderful. I love that. I've never heard that before.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:44:42] Yeah.

Scott Langdon [00:44:44] Well, while we were in preparation for this episode, you sent me an email where we talked about these two emails and what we had in mind, and what you had in mind. And I thought it would be a really good idea if you read that email right now as we close out this episode.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:45:01] Yeah. Well, I wrote in that email, just trying to think ahead, you know, having read these again, what we might be talking about. And I said, what strikes me about Gerald and Margaret is that they exemplify or explore two of the main obstacles- obstacles to relating to the divine. Gerald tends to dismiss it, and for understandable reasons. You know, we can't be down on the people who are skeptical. These are understandable reasons. It is important to recognize that doubt is not just stubbornness, often it's not just stubbornness. Up to a point, it's a healthy skepticism. Now, Margaret has some excellent experiences of connection, but acknowledges a problem with will intervening. That is also a common experience. It would be interesting to explore why this is so. You know, why do we do that? We human beings, most basic human instincts are functional. At least that's my view, though, when they run away with us, they become dysfunctional. They need to stay in their function, you might say.

Scott Langdon [00:46:17] Right. Right. Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:46:18] What is or should be the role of the will, and how are we to know when it is, let's say, misbehaving? And I am assuming that the will is in part an engine of activity. You know, we're goal oriented people, we're teleological beings. We have purposes and we try to get somewhere. You're trying to, you and your colleagues trying to put on a play, or whatever.

Scott Langdon [00:46:51] Right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:46:51] And, so, there's a lot of your will energy. You know, you're mobilizing that to this end. But if will, in that sense of the engine of activity, becomes willfulness, then it's reflecting not on the goal of the activity, which in that case is a common goal, though it could be just one trying to do something oneself, to write something, or preparing a presentation, or something. But the willfulness starts is self-referential and starts working against the purpose. It starts working for its own self, much the way Margaret was describing. Ah oh, I start working for my will. Life kind of goes down the drain. It was peaceful before. I was in the divine presence. Simple. Simple. You think be simple not to get willful? But there it marches in yourself. This wonderful woman who's close to God, nevertheless, like all of us, has these moments when willfulness or something else intervenes. So here are Gerald with his skepticism, which again, is healthy up to a point. The skepticism ideally is in the service of finding the truth.

Scott Langdon [00:48:10] Right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:48:10] So you want to be skeptical of untrue stories of the false leads or semblance of truth, illusions or crowd psychology or something. And it becomes bad when the skepticism kind of just feeds on itself.

Scott Langdon [00:48:28] Mm hmm.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:48:29] That you become almost proud of not believing anything. And, you know, they used to have this concept of the village atheist, which was the person who just went around spending all day, right, say refuting every religious belief, as if that were an end in itself. Well, he's wasting his life not just because there is a God, but because he can probably go do something useful with his life other than criticizing the believers. So, a lot of the challenge of life and connecting with the divine is a huge help here, is to keep your intellect pointed towards the truth in a fruitful, constructive way, not in a self-centered way. And to keep your willfulness, energizing, purposeful activities that are good and you chose to do, and not turning back on itself and creating obstacles. So that, I think, would be one lesson from Gerald and Margaret.

Scott Langdon [00:49:43] Thank you for listening. To God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. Subscribe for free today wherever you listen to your podcasts and hear a new episode every week. You can hear the complete dramatic adaptation of God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin, by beginning with episode one of our podcast and listening through its conclusion with Episode 44. You can read the original true story in the book from which this podcast is adapted. God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher, available now at Amazon.com, and always at godanautobiography.com. Pick up your own copy today. If you have any questions about this or any other episode, please email us at questions@godanautobiography.com and experience the world from God's perspective as it was told to a philosopher. This is Scott Langdon. I'll see you next time.