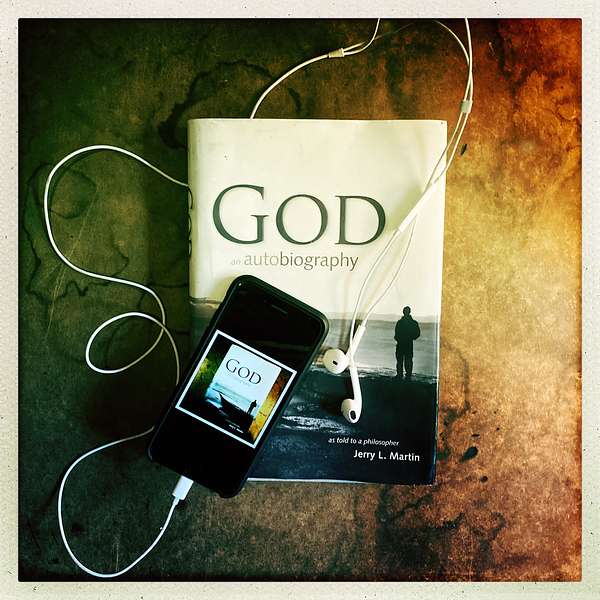

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

162. What's On Our Mind- Embracing the Drama of Life: Reflections on Suffering and the Inconvenient God

In a special episode of What's On Our Mind, Scott Langdon and Dr. Jerry L. Martin reflect on suffering and divine perspectives. Revisiting Jonathan Weidenbaum's rejection of nihilism after a year of loss, they discuss unconventional responses to suffering and the search for meaning.

The hosts explore the ineffable nature of the divine, emphasizing the interconnectedness between playing a character and our relationship with God. The conversation touches on free will, the nature of evil, and the challenges of understanding God's role in our lives.

Jerry revisits an Inconvenient God, and Scott shares insights from his acting roles, both encountering God's engagement in the intricacies of human experience. Subscribe for weekly episodes and explore profound insights in this ongoing exploration of God's story.

Relevant Episodes:

- [The Life Wisdom Project] The Encounter With Novelty And Living Truthfully | Spiritual Resilience: Navigating Loss and Finding Meaning

- [From God To Jerry To You] An Inconvenient God

Other Series:

The podcast began with the Dramatic Adaptation of the book and now has several series:

- Life Wisdom Project: How to live a wiser, happier, and more meaningful life with special guests.

- From God To Jerry To You: Calling for the attention of spiritual seekers everywhere, featuring breakthroughs, pathways, and illuminations.

- Two Philosophers Wrestle With God: Sit in on a dialogue between philosophers about God and the questions we all have.

- What's On Our Mind- Connect the dots with Jerry and Scott over the most recent series of episodes.

- What's On Your Mind: What are readers and listeners saying? What is God saying?

Resources:

- READ: "A Step in the Right Direction."

- WATCH: An Inconvenient God

- WHAT'S ON OUR MIND PLAYLIST

Hashtags: #whatsonourmind #godanautobiography #experiencegod

Would you like to be featured on the show or have questions about spirituality or divine communication? Share your story or experience with G

Share Your Story | Site | Facebook | Instagram | Twitter | YouTube

Scott Langdon [00:00:17] This is God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. A dramatic adaptation and continuing discussion of the book God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin. He was a lifelong agnostic, but one day he had an occasion to pray. To his vast surprise, God answered- in words. Being a philosopher, he had a lot of questions, and God had a lot to tell him. Episode 162.

Scott Langdon [00:01:07] Hello and welcome to episode 162 of God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. I'm your host, Scott Langdon. This week on the podcast, Jerry and I share What's On Our Mind after a series of episodes that focused pretty heavily on suffering. In our 13th edition of the Life Wisdom Project series, Jonathan Weidenbaum returned to talk about his views on episode 13 after having endured a very difficult year of his own. As we discuss Jonathan's choices and what he found during his journey, Jerry and I also talk about God's role in all of our suffering. Where is God when all seems to be going wrong? Where do we look to find God, and how do we know when we've found Him? Thanks for spending this time with us. I hope you enjoy the episode.

Scott Langdon [00:02:00] God tells us this, I think in virtually every religion that I know, there's some kind of message from God that is- if you seek Me, you will find Me. We talk about that as a promise in Christianity- that God has made a promise of that. Judaism is the same thing- God's promise is. In some of the other religions, it's not even talked about in the relationship way. It's talked about as this is the way things are. You just are in a relationship with God. In much the same way I talk about playing a character. You know, I just finished playing Lord Aster in Peter and the Starcatcher. And again, as we've talked about before, when you come to see that play, there is no Lord Aster without me, and yet there is that separation. And there's a lot of implications there about things I learned about myself by playing Lord Aster, by encountering the other characters in Peter and the Starcatcher as Lord Aster, but Scott Langdon sort of in the background as the illuminating force of Lord Aster, still participates fully spiritually in what's going on with these characters. Crying real tears when my daughter, the character who is my daughter, is going through a difficult time. Well, those are Scott's tears, but they're Lord Aster's- you can't separate them. And so that implication of God being so not only in tune with us, but just is simultaneously being us. We are-- we can't be without God. It's such a beautiful thing to be able to talk about it in all kinds of different ways, because in the end, that's what we're doing, right, is just trying to articulate the-- what seems to be ineffable-- the inarticulable.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:03:49] Yes, yes. I never like to talk about it as ineffable, because in fact, we can talk about God a whole lot.

Scott Langdon [00:03:57] Yeah, yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:03:58] And a lot of what we say is true, or at least, has a good chance of being true, you know. And so, you go too far in the ineffability, of course, you can never adequately state it. A friend of mine says the taste of a banana is ineffable. How would you describe to someone, you know what a banana tastes like? Well, lots of things in life are not easy to articulate. And so, the divine, of course, is going to be very different. You can't pin God down or pin the divine, which is bigger than the personal face of God, of the divine, you can't pin it down. But there are lots of things you can say and lots of things we know through our religious experience and include you couldn't-- those people who want to say God is ineffable know that through actually knowing God and knowing the divine. Then they come back and report, I've been there, I have visited the divine, and the divine is ineffable, and that's one of their conclusions from their experience. That's a way of expressing something that is sort of true if you don't draw the wrong implications from it, namely, that we know nothing about the divine because we do.

Scott Langdon [00:05:22] In episode 160, we had Jonathan Weidenbaum back. And this was Life Wisdom number 13, and we had Jonathan Weidenbaum back because a year ago, last year-- so, it was December 29th of 2022, Jonathan was on, I think it was the third Life Wisdom episode, and some great things had happened in his life. He had recently gotten married. He had recently lots of joy had come to his life, and we were talking about something completely different in those episodes. Now, here we are a year later, and his wife has passed away. And he recently, within the last month and a half, lost his mother as well. And during the conversation that you had about episode number 13, where you ask God some really hard questions about suffering, you reached out to Jonathan, your good friend, and said, would you like to come back and talk about this? And he realized why you had chosen him for that episode, because it had been a really difficult year. And so, this is one of the things that's been on my mind for a while and wanted to talk to you about it as I've edited the episode and as I've listened to it a couple of times and really have been digging into his words to you and your words to him. One of the things that he said was that through this experience that he had of his wife dying so suddenly and then losing his mother and all of these things--

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:06:52] And it was a recent marriage, let me add that. He had just found her. You might say late in life. He would become middle aged, I guess. And finally, after having been single all those years and a quintessential bachelor living in downtown Manhattan in his own apartment and so forth, he found Ms. Right. They got married, and then within a year or two years, I don't know the exact time- bang. Fast moving cancer I believe, she's gone. So, you know, and I think how does one handle that? And I told Jonathan to talk about it only if you feel comfortable coming on. Because I wouldn't be surprised if he didn't. I would-- it's painful even to say what I said. Much less to be Jonathan. But anyway, go on. You're going to talk about that discussion in that Life Wisdom episode about suffering.

Scott Langdon [00:07:52] Yeah. What struck me, among many things, and I wrote several things down. But one of the biggest things that struck me was that he said that through all this experience, kind of the opposite of what one might think would happen, actually happened to him. And that is that nihilism to him made even less sense now through this suffering and through these experiences. So usually we think, you know, and maybe what happens often with folks is something very difficult will happen, somebody will die, or some other tragic event, and we say, "There is no God; there's nothing to this. There's no meaning to this." We can't, you know-- and yet he found the exact opposite to be true, that it was full of rich, rich meaning. Great depth of meaning. I found that really fascinating and interesting and uplifting.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:08:46] Yeah, that was very striking. And yet nihilism comes from the Latin word nihil, meaning nothing. It's no God, no meaning- no meaning to anything. No right and wrong. No nothing. No nothing! And you would think, and I thought when I first heard his experience, I thought, this isn't just suffering. This is tragic suffering. And what I meant by that is the kind of suffering, you know, we all have suffering, and some people have worse suffering than others, but this is the kind of suffering that would call into question the meaning of your life- would seem to upend the meaning of your life, and thereby suggest life is meaningless, is absurd as they often say. And this is amazing to me that Jonathan says, "No. No, quite the opposite." And having known Jonathan now for several years, sometimes-- he lives in New York, so he's close enough that we've visited with each other a few times-- that knowing Jonathan over the years, I can tell the difference. There's a solidity and depth to him. As if a kind of you might call it maturity, but it's deeper than just simply growing up and maturity. It's carrying a deeper understanding of the world, of life, of meaning, and I don't know if-- I don't know how to express that, but he expressed it by saying nihilism is even less plausible to him now. He's found through the very suffering, I guess part of it would be you often-- it's only when you lose something that you realize darn, that was good. That was important. That was vital. And you lose it, and then you think, why didn't I understand that at the time? I think he did kind of understand the preciousness of this love he had found, but the loss of it often drives the lesson home.

Scott Langdon [00:10:54] Mhm, mhm. He also mentioned that he found that the experiences didn't mean there was a God or not a God per se. They're not to answer those kinds of questions. But instead, it was more that-- and not to get meaning from it in the sense of like, oh, now there is a God, or oh, you know, it could be that, and it's not necessarily that. But other meanings like hold on to your loved ones now; make sure you're saying the things that you mean to say; don't let your son go down on anger- those kinds of things that we've all heard. Sayings like that, they become cliche, even, but we realize that that is a meaning of how to do life. Yes, every time you can remember to think of your loved ones in a wonderful way-- if you feel the instinct to call your mom, call her. If you-- you know what I mean-- like if there's something that's out of sync and doesn't feel right-- what can I do to fix this relationship? And it always feels one way or the other. You don't always necessarily know what to do, but you know this relationship, it needs something. You know, so we're always making meaning about what that might be, but it goes back to the step beyond that, which is recognizing that that's what this life is, is about the doing about the working it out, about the noticing the things that are meaningful and recognizing them as such because they are fleeting in that sense, it's ineffable. Like, what do you mean about I love Abigail, you know, you can't really talk about what the feeling is, you can only talk about what it makes you want to do.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:12:52] You know that's true. Any time you try to talk about the feeling, you know what it is to love Abigail, you go reductionist. You're giving a little textbook thing that doesn't capture the experience at all. And when I first fell in love, I went and read the relationship books because I hadn't-- I didn't even know-- I didn't believe in love. I didn't believe in romantic love. I thought I was looking for compatibility. You know, something much more ordinary, and this kind of blew my mind such that I've got to go read up about this. Well, I found what the experts kept saying, "Oh, it's projection. It'll dissolve in about six months." And, you know, "the scales will fall from your eyes and you'll say I thought she was perfect, but she's not perfect. Oh, no." Another girlfriend bit the dust, you know? But I thought this isn't right at all. It has nothing to do with her being perfect. I'm not perfect. She's not perfect. Why would I look for-- it has nothing to do with I found the perfect woman. No, I found the woman I fell in love with is what I found, that I loved and loved deeply in a way that was shocking to me and almost changed me, you might say my ontology, my sense of what the world is, and had to think, "Whoa, what is this?" But that's part of why I always think in terms of a drama. Not that putting her in a drama would-- that would be reductionist also, as if this is a move at a play, but life does have these moments and the moments are revealing and what they have to teach you want to make sure you learn. And Jonathan's doing a bang-up job there, I must say, in probing this- in probing it and taking in the wisdom from it.

Scott Langdon [00:15:07] One of the things I noticed in this last play that I just did-- we just closed on Christmas Eve-- is, and I've noticed this before, and I think we might have even talked about this before, that one of the reasons I like to do plays, stage work, is that during a run of the play, like every night, we do say a show eight times a week, every time you do it, you know how it's going to start and you know how it's going to end. So, 2.5 hours of this story, it's the same story every week or every time you do it. So, I go in and play this character and we play this story the same way, but of course it's different because it's a different audience and it's a new moment in time. But what I found out, what I've really leaned into this time was going on the ride of the story, playing my character, but also trying to kind of notice different things about the story along the way, and notice how I'm noticing different things about the story along the way. So, in a sense, almost trying to separate myself from the character Lord Aster that I'm playing, in a way. And I say that because what was interesting to me about observing that is that it honed my desire to want to be more in the present moment, in my every day, in Scott Langdon's every day. That doing this play every night I could see, I kind of knew what was coming. I could kind of feel what was going on, and Lord Aster doesn't know, but there's a sense in which he does know, because I know. And so, when we're in sync, we hit all the right lights, we hit all the right technical stuff, but we also have a connection that the audience feels. That the girl playing my daughter and I, for example, are having a real moment. The audience feels that existence going on. And so, the reason I'm talking about all this is that I have a chance to do that eight times a week and observe it. So, now in life I'm like, this is only going to happen once, and let me make sure I'm really paying attention to this, and that has been a real gift of being able to sort of see my work in that way, and also kind of wonder, how is God taking in the world from each of our perspectives, our own unique perspectives? So, God as us, as we've talked about before, is God learning? Is God-- You know, it's fascinating to me that God might have a similar experience that I just described to you.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:17:52] Yeah, I think that's quite right that part of the strangeness of God: An Autobiography, in terms of any conventional understanding, is that God has experiences, desires, disappointments. God suffers when we suffer not only out of commiseration, but as you might put it, well, that's part of God. Just, you know, like a hammer hits my finger, it's not just the finger that suffers. I remember Ronald Reagan at one point having cancer, he said, "I don't have cancer. My nose has cancer." Well, it doesn't quite work that way.

Scott Langdon [00:18:32] Right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:18:32] The hammer hits my finger, it hurts, and it hurts God's. This is also God's finger, and it hurts God, but moreover, when we do something bad that hurts God. God thinks, "Oh, no. Oh, no." And you certainly see that in the Old Testament. I don't know if you see it in the new or not, but you certainly see it that God at one point says, regretted ever making the world, you know, or creating humanity, creating people. And I prayed about that, and God said, "No, no, I never regretted it." But God reacts when we go wrong. And so, something like what the Nazis did, it wasn't just bad to the Jews and God felt for the pain of the Jews, but with the Holocaust He felt pain, you might say, for the Nazis being so bad as if God were their parents. You know, think of how their parents, if their parents were decent people, would have thought, "Oh, no, my son has become a Nazi. He's running a concentration camp." Oh, you know, that's the pits. That's the worst. So anyway, that's one aspect of the whole thing. We live a drama, God lives a drama, and we are living the drama with God. God is living it in part through us. God says at one point told me; the people's stories are My story. Put them all together- they're My story.

Scott Langdon [00:19:56] Yeah. You know, that's so interesting about the suffering and the cause of suffering. You talked with Jonathan Weidenbaum about different types of suffering, and I'm interested in what you just mentioned about the Nazis and God's sort of opinion of that. Like how would that be? And so, then the argument might be, well, if God is-- if the essential nature of every human being is God, then why couldn't God just make the Nazi person not be a Nazi? And that's a great point. Like, how could God allow suffering? That's sort of the classic question, right? Well, thinking about what I just mentioned about being an actor and stepping into this role, I have thought that many times about characters that I've played. "Oh, Uncle Ernie," in The Who's Tommy, "oh Uncle Ernie," I say, "don't make that choice to abuse Tommy," but I have to do it every time I go on because that's that story. Do you see what I mean? It wouldn't be that story if Scott Langdon altered what Uncle Ernie has to do, if you know what I mean. Uncle Ernie has a role to play. Hitler had a role to play-- it's that's how the story unfolded. I have such a difficulty with that. I know I have caused suffering in my children's lives, my friends, my parents. I know I've caused the suffering. And so I go, why couldn't God just make me not do that? Well, what have we been talking about? There have been these nudges. It never felt right to do a thing that would cause suffering. Maybe there is always God trying to tell me. At the same time, it wouldn't be the story. It is if those things don't happen the way they happen.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:21:44] Yeah. We each have our own stories and we each have a freedom which God says, I don't even know what I'm going to do next. You know, God has freedom. We have freedom. And so that's part of it. We have to live out our stories. We can live them well or badly. But at one point, I had this exchange with God about somehow focusing on Lady Macbeth, who's just a perfect example of a wicked person.

Scott Langdon [00:22:10] Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:22:11] And bringing her husband down too, you know, boiling him in wickedness, and I can't remember the details now, but God was in some way saying yes, that's part of the story. And of course, there would be no Macbeth without Lady Macbeth and all of that treachery. Right? And we learn truths from Macbeth, right? And perhaps had they been real people, they might have learned truths to the extent they gained insight from it. But I was arguing with God, as I often do, and saying but that sounds if you're saying, yeah, like evil is okay. "No, I'm not saying," God says, "No, that's as if you're not listening to Me."

Scott Langdon [00:22:57] Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:22:58] You know? He didn't say that. God didn't say that to me. God just said this is part of the complex, dramatic tapestry of the world. And, okay, that doesn't-- but this is the part you got to fight against. You got to fight. You got to get rid of Hitler if you can. You got to liberate those camps if you can, and so on. And you got to fight the evil within yourself if you can, you know? And that's the biggest struggle ever, I'm told, is always trying to control one's own chaotic, let's call them, impulses-- what the Jewish tradition called the evil impulse, often. Just egoistic self-assertion that can lead one to be cruel or push people around or tyrannical. We got to control those things as best we can, but they're part of the story. And at one point I should mention this because we've run an episode. I don't know the number from God to Jerry, to You. I was telling the God story, the story of the God book to a guy who's going to help us publicize it, and he said, "These days, we like convenience. Everything is about convenience. This sounds like a very inconvenient God." And that's true. There's not a-- God says, "I'm not like a rescue helicopter who comes down and snatches you out of a difficult situation or takes a grandma who's about to die to the emergency room and has the miracle cure." No, that's not what it's about. And so, I wrote a piece that I put on YouTube, and we've done the audio for one of our podcast called An Inconvenient God. And so, and you have to think it through, when I try to do that, I'm often in my own version of faith seeking understanding, which is the classic definition of theology, what theology is, my own version of that is often taking what God has told me. This collection of long conversations with God and trying to make sense of them. What are the implications of this? Why is God an inconvenient God? And I try to explore that in this episode called An Inconvenient God, but that's part of the picture. And part of the picture is Jonathan's suffering, and dealing with people who are just wicked. And you think, well, what's that about? Is God present there? And well, yeah. If there's a real Lady Macbeth, God is also, you might say, enacting Lady Macbeth at the same time, telling her the way you tell, you know, your character don't do that. Don't do that. But there it goes. The character has freedom or an author, there's not you and doing what that character does.

Scott Langdon [00:26:02] Well, Jerry, it's always great to talk to you and I'm so glad we had the session again. I love these episodes.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:26:05] Yeah. Yeah, it's great Scott, and appreciate it.

Scott Langdon [00:26:28] Thank you for listening to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. Subscribe for free today wherever you listen to your podcasts and hear a new episode every week. You can hear the complete dramatic adaptation of God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin by beginning with episode one of our podcast and listening through its conclusion with Episode 44. You can read the original true story in the book from which this podcast is adapted, God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher, available now at amazon.com, and always at godanautobiography.com. Pick up your own copy today. If you have any questions about this or any other episode, please email us at questions@godanautobiography.com, and experience the world from God's perspective as it was told to a philosopher. This is Scott Langdon. I'll see you next time.