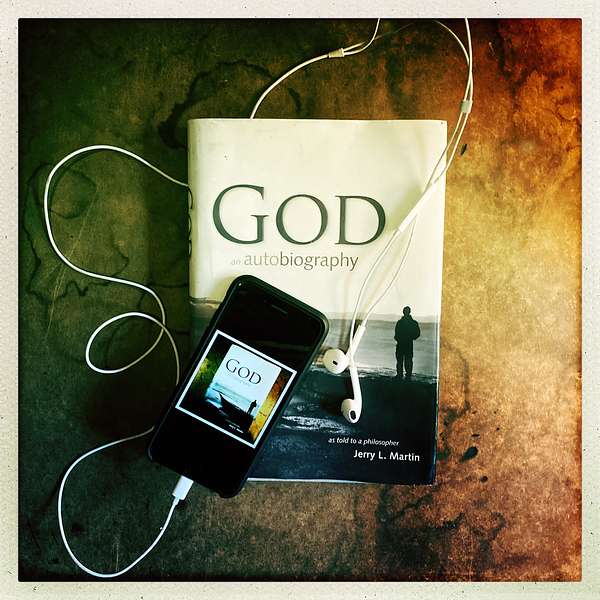

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

175. The Life Wisdom Project | Exploring Divine Creation: Beyond Philosophy| Special Guest Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum

In this episode of The Life Wisdom Project, join host Scott Langdon and Dr. Jerry L. Martin alongside special guest Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum as they explore the vivid drama and insights from God Takes Me Back To The Beginning Of Everything.

From exploring the divine creation and personal revelation to unraveling the meaning of existence and the essence of personhood, this episode takes listeners on a thought-provoking journey through the depths of spirituality and philosophy.

Discover the beauty of aesthetic flow in creation, the evolution of relationships, and the embrace of the unfinished cosmos. Dr. Weidenbaum and Dr. Martin go beyond traditional philosophy to discuss the drama of the divine and existence, offering fresh perspectives and intriguing insights.

Tune in for a captivating exploration of life's mysteries and stay connected with God: An Autobiography, The Podcast for more profound conversations.

Meet Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum, who teaches courses in philosophy, world religions, ethics, and bioethics at Berkeley College in NYC and St John’s University in Queens. He writes and publishes in the philosophy of religion and the philosophy of humor, among other topics.

Relevant Episodes:

- [Dramatic Adaptation] God Takes Me Back to the Beginning of Everything

Other Series:

- Life Wisdom Project- How to live a wiser, happier, and more meaningful life with special guests.

- From God To Jerry To You- A series calling for the attention of spiritual seekers everywhere, featuring breakthroughs, pathways, and illuminations.

- Two Philosophers Wrestle With God- Sit in on a dialogue between philosophers about God and the questions we all have.

- What's On Our Mind- Connect the dots with Jerry and Scott over the most recent series of episodes.

- What's On Your Mind- What are readers and listeners saying? What is God saying?

Resources:

- READ: "I Breathe Life Into Matter."

- THE LIFE WISDOM PROJECT PLAYLIST

Hashtags: #lifewisdomproject #godanautobiography #experiencegod

Share your story or experience with God! We'd love to hear from you! 🎙️

Share Your Story | Site | Facebook | Instagram | Twitter | YouTube

Scott Langdon 00:17: This is God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. A dramatic adaptation and continuing discussion of the book God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin. He was a lifelong agnostic, but one day he had an occasion to pray. To his vast surprise, God answered- in words. Being a philosopher, he had a lot of questions, and God had a lot to tell him. Episode 175. Welcome to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast, and episode 175. I'm Scott Langdon and this week it's time for another installment of the Life Wisdom Project. In today's episode, Jerry sits down once again with Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum and the two break down Episode 16. God Takes Me Back to the Beginning of Everything. They unpack just a few of the many implications from episode 16 about how to live our lives, as well as what it might mean to have a God who is developing with us, as us, and alongside us. You'll remember Jonathan from episode 160, a Life Wisdom episode we called Spiritual Resilience, Navigating Loss and Finding Meaning. Check that episode out to hear more from Jerry and Jonathan if you haven’t already. Here, now are Jerry and Jonathan with this week’s Life Wisdom Project. I hope you enjoy the episode.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 02:14: And so, Jonathan Weidenbaum, thank you for doing this Life Wisdom discussion with me on episode 16. I think, I don't know what it's officially called, I always think of it as creation because it's the emergence of the world and God simultaneously. And as I was—we exchanged thoughts a little beforehand and my suggestion was we're going to relate this to our lives as individuals, as persons, take seriously what I'm told here, the idea that God is a person.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 02:43: And if you look at it from that point of view, you know God says re-experience that moment- He's asking us to kind of share God's experience of the beginning of the world, which is a lot like a neonate or something. In fact, it just made no sense at all to me. “I'm in the midst of Nothingness,” well, that might be a lot what it’s like to be in the mother's womb, right? You're just in darkness and not much going on, and then, whoa, suddenly you're ejected and everything's sort of chaos and your experience is just a chaos at that point and you have little arms and legs but you can't do much with them, and so on, and then it goes on from there. Does that make sense to you, Jonathan?

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 03:35: It puzzles me also, the idea of being in a nothingness. And I mean there's a lot of sort of cosmological and philosophical sort of paradoxes there to unpack. I don't even know if paradox is the right word, but a lot to unpack. But certainly, there is a tremendous amount here that is relevant for life, for questions of how we should live our lives, for questions of how we should live our lives. And you know it's interesting, one can maybe interpret your entire book as a series of revelations to you, as a body of religious experiences, a series of religious experiences of God revealing Himself to you. And I know that in the beginning of the varieties, William James offers three criteria for assessing the verticality or the truth-bearing nature of religious experience- immediate luminosity, how much it grips, philosophical reasonableness, how it fits into everything else we believe about the universe and moral fruitfulness. And if you don't mind, I'd like to concentrate on the last of those.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 04:48: Because the question that we're not exploring is whether it's true or not. I just want to talk about the moral meaning of all that's suggested in this really, really rich chapter. And I got a little bit of a high from it because, if you remember, some of my own scholarship deals with William James's idea of a finite God. You know, a God that is not an absolute in the sense that 100% mastery of everything, rather a God that Himself, Itself, Herself has a history and develops over time and faces some kind of environment of its own, even if it's larger than ourselves. You know so, of course, I don't forget that this God, who reveals Himself to you, if you don't mind me saying Himself, is a person, and yet more than a person, and this God has a history. The images of this God stretching its aching muscles, punching out its arms and legs.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 05:59: “I scramble to take control to provide order.” You know it's interesting, not only does the idea of a finite God resonate with me, with my interest in William James, and also some tendencies in the Jewish mystical tradition as well, but you turned me on to a book, Jerry. Yes, in your book God: An Autobiography. As Told to a Philosopher, I learned of Jon D. Levenson's book Creation, and of course, I read the book.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 06:33: The title is Creation and the Persistence of Evil, by Jon, spelled J-O-N Levenson.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 06:40: That's right. And this idea I mean I just love... I mean, look, I'm no bible scholar, you know, but here is a bible scholar, from the Jewish tradition, talking about sort of a god that has only kind of semi-tamed this cosmos and is always trying to keep the great abyss in check. And of course, I think he suggests in either the preface or introduction to the book he's not trying to suggest along the lines of process theologians, of a guy that's intrinsically finite but still, yet, still a cosmos that's only partly put into abeyance, so to speak, and that nothingness is always- the waters are always sort of partially threatened to re-flood or to submerge us in this. So, I'm struck by these images from your chapter.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 07:45: According to Levenson, I think he's saying this about goodness but divine goodness, divine sovereignty, is ultimate but not proximate. In other words, it's the big story either at the end or from the ultimate perspective. But meanwhile, where we are, you might say, it's a work in progress. God is aborning, coming into being through this history, through this struggle against chaos and against evil, you might say.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 08:22: That’s right, I mean, I love this quote, “But Lord, You are admitting serious limitations as You scramble to create order out of chaos.” And of course, you know that's your quote from the text from your conversation with God. Of course, yes, in the Levenson book, this God is not intrinsically finite, rather, you know, how prayer in the Bible, according to Levenson, is performative. It's in a sense trying to no, performative, that's not the right word it's trying to invoke, you know, it's trying to kind of get God to complete its dominion, so to speak, or his or her dominion, you know, whereas these limitations are intrinsic, even if this God has, as he states I already had unimaginable power and knowledge. You know, limitations only from my perspective, he says, but still, you know this deity that is greater and more extensive than us, that's a person, yet more than a person, has an environment, has an outside to himself that you know, and has a history and grows all his own.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 09:30: And to me, that has tremendous implications for questions of the meaning of the moral life. So, when someone like William James, underpinning so much of his ideas as this idea of trying to inculcate the morally strenuous- the morally strenuous mood, but in order to do, part of how he attempts to do that is rejecting this absolutist, absolute idealist picture of a cosmos that's really just God by another name. And to invoke a God that himself is in struggle and the idea that we are partners with this God and you know this, trying as sort of this idea of an unfinished cosmos is what kind of invigorates us to want to do. It kind of gives meaning to our efforts.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 10:28: That’s William James, isn't it? And what God says here, well first, God is lonely, you know, you can just be the cosmic one- that's kind of lonely. And second, somehow God needs resistance, and did you pick up on that?

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 10:48: I did, in fact, I underlined that.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 10:51: Yeah.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 10:51: God says, “Before Creation, I am pure spirit, sufficient unto Myself. I felt I was lacking something--grounding, facticity, the blunt materiality, the hard edge to push oneself against, the resistance and friction that physical objects have.” And you know, I was thinking about quotes to talk about. Well, that's one of the quotes, but yet I want to invoke a quote that I find meaningful by way of contrast to this, a contrast in which I hold this quote favorably because in one of the Upanishads, understood in a kind of Advaita Vedanta kind of perspective, which sees this world of plurality as really ultimately Maya, that everything is nothing but Brahman in different forms, the ultimate expansive Satyananda, bliss, consciousness, awareness.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 11:53: And there's a quote- all fear comes from the other, or anxiety comes from the other. That is, if you're caught up in the illusion of plurality and duality, then there's something outside of you that opposes you, whereas if you realize that your true nature is one with the absolute, then duality and plurality are nothing but (you'll see that they're) illusions and you're able to shove off that anxiety, the fear. Whereas, I see the God of the God, book of the God: An Autobiography, as kind of pushing in the opposite direction. If Himself wants an outside, an other, without which real relationship is not possible, without which we cannot exert our energies, as with God, so with us. So, I appreciate it by way of contrast with a more a cosmistic universe, which deems the universe as an illusion, whereas the God of the God book, of God: An Autobiography is one for whom, no, this multifaceted, pluralistic cosmos that God creates is of an inherent value, and real otherness is one of the conditions for genuine relationships.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 13:17: Yeah, I think that's the conclusion here, if you just stated it, Jonathan, that for the world to be real, it has to offer resistance.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 13:29: There's no point. Often in the Hindu tradition, in certain versions, they talk as if the world of appearances, objects are the world of appearances and they're like divine play, as if, like a virtual reality, that God has a computer game or something. But what I'm told here is that no, God needs a real world. He needs a real world and, moreover, a real world is unfinished and God is unfinished. What do you do with the child? You don't just bring it a bottle for the rest of its life. You have it learn things, you give it challenges, and that's what you do with the child, with the young adult, with each other. We give each other challenges and that's how we grow and how the world itself comes into fulfillment, along with God coming into fulfillment.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 14:33: And yet, there is also… Yet, in this story, there is also something of that wonderful play that sort of that great show that is the cosmos, you know. “Yes, I wanted more. In retrospect, the inanimate years feel very lonely. The emergence of life is a delight. With life, spirit comes into play. Wonderful to see amoeba, moss, and so forth.” A bit later, “I love their myriad forms. I am not alone anymore.” There is this sense in which…

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 15:10: It was my plaything. It makes beautiful sounds, delightedly playing with it. The cosmos was my playpen, beautiful, dazzling. But it's not play in the sense of unreal so much as it's real and wonderful.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 15:27: Yeah. So it captures that spirit of this multicolor, multifarious, multi-sided universe, yet without rejecting its reality, without falling into a cosmism. It captures the play aspect of Lila Rasa that we see in Vedanta, yet without the relativizing of the world, without demeanized derivative to something more basic, and I like that. I like that balance. There's a lot of balance that comes. There's so much that is synthetic in the God book, so much that speaks to the mystical element yet at the same time to the realist element, and I happen to appreciate that.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 16:41: I absolutely– this quote here is worthy of, like you know, of being very well known, “I could not become a Person without there being other persons.” And then, right here, “The personal is essentially interpersonal.”

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 17:07: There's a whole book– you can unpack a book of wisdom on that quote alone. You know, I mean, look, it doesn't even need to be spelled out, it's almost like I don't want to beat it to death because it's right there. It's just to be a self means to be related to what is not self, and really, truly, not only not self, like that wall, but not self, another self, and that's what God needs. God is happy to have frogs and amoebas and bears and dogs. That's all lovely, you know. They're less separate from him. The world is much less dualistic, more holistic, He says, instinctual, unselfconscious rapport that they have, I'm quoting from the book. But ultimately it's not enough. God needs to be set off from and against and related to other-selves.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 18:07: From full persons. The animals are wonderful, Totally delights in the animals. They even have a soul, I'm told somewhere in the book, but they lack, this is at least one key to the difference that comes out here, He says but they have no second-order reflection, they sort of just are. You know, they move instincts from one moment to the next and that's fine if you're a dog, that's what you're supposed to do, that's your nature and serves your purpose, and so on. But to relate fully, you know, as you and I relate well, we each have a second-order consciousness. We're not only relating where we are aware that we are relating, and then that opens whole further dimensions. And yet we each have to be really real, otherwise, it's not a relation. And the fact that we're embodied is a big plus, you know that's part of the story.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 19:12: I must say the chapter pleases me also, even aesthetically. The way it's sort of– the movement of it, you know.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin: Explain that.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum: Okay, sure, we go back to the very beginning. The language itself is beautiful. So we go back to the beginning, “Enter into Me and experience the beginning as I experienced it,” you know. So, then there's the Nothing.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 19:43: Then there is this– God is almost a primordial baby type thing. I don't mean that disrespectfully, but the opposite. Pushing out its arms, you know stretching aching muscles, scrambling to control, and then you know this God wanting otherness, wanting something to press up against. I love that image. I think James has something similar to that. You know, that there's just something in our nature that wants something to press up against. So, with God, then the creation of the animals and the beauty of that, and the magic show of reality and how animals are kind of instinctually in tune with him, non-duality, and then this realization, but wait a minute, I need a higher level of awareness. And then it ends with and so I created mankind.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 20:37: You know, sort of pointing to the next chapter. I mean, I just kind of just gave a basic replay of the chapter rather than explain why it's aesthetically pleasing, but there's a movement, there's a flow, there's a sort of, you know, a kind of a dynamism that's pleasing here. It takes us for a ride. It takes us for a kind of like, puts us on a boat and takes us from one place to another, and the transfer of images and themes is something about it, you know, and the way it ends it's a kind of a cliffhanger, it's like you know, now we know next chapter is a very, very important one.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 21:22: Yes, we need persons.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 21:25: It's pointing outside of itself. Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 21:27: Yeah, and then what will happen once we do get persons?

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum: Right. Right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin: What you're seeing is a kind of aesthetic flow.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 21:37: Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 21:37: At a certain level that must be the flow of the divine experience, unfolding of the world, because here God comes into being with the world, rather than being particularly pre-existing, though there's nothing in the book, but also it may be you might say the natural flow of our own lives. They're constantly interrupted and disrupted. But then you might say the natural or ideal flow of our lives, and you see this, if you hang around young kids before horrible things have happened or they've gotten too involved, you know there's just tremendous flow in their lives, a kind of playfulness and learning and a wonderment. I have a little picture of my kids where one of them is looking over at what the other one is doing with this most intense interest in more or less nothing that's going on. But this intense interest is kind of the natural flow of life and a shame it gets distorted and you know, interrupted, and so forth.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 22:50: You know what? I'm also reminded of in Peirce's category, this might be a stretch here. Charles Peirce speaks of firstness, secondness, and thirdness. Firstness is just raw, pure immediacy, like basking in a nothingness, in the here, and then all of a sudden meeting other, the dyadic relationship, something to push up against, you know, a reaction. And then, of course, the thirdness is kind of law or habits which sort of mediates between the two. So, there's a sort of… It might be kind of pushing out the edge here; I might be grasping here, but there is something of that. There is some of this almost we're watching three stages here. Pure immediacy, then reaction, you know, then relation to what's not me, and then reflection.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 23:47: Yes, reflection and norms. One of the things I was struck when just life is emerging, well, He says, now we have life and all these beings, animals, creatures, begin to stir on the earth are amazing, God says. There's birth, growth, death, mating, offspring, colonies and flocks, and emergent social orders. You know, among the animals, their social life is very amazingly complicated if you study it in rich. And ideality as well. Because once you're going somewhere in life, even at a kind of basic level, norms come in. There's better and worse, there's sickness and there's health, there's getting food and failing to get food, there's planting the seeds and failing to plant them or whatever you're doing, rooting up the seeds. And telos, and purpose, success, and failure, standards of perfection and imperfection come in at that stage, not yet as rich as with other persons, homo-sapiens, but already emerging in ideality, purpose, standards of perfection, imperfection, success, and failure are kind of crucial to the picture here. What are you about?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 25:16: God's trying to bring God's self into being. In the process, we are coming into being, in cooperation, response to, and cooperation with God's self. And there's a telos to it all that’s not discussed much here, but one kind of knows. Well, the personal is interpersonal. That's already a kind of normative standard. You obviously let it down. Martin Buber talks about the I-thou relation or the I-it relation. So you can treat people as if they were just objects. Well, that's not adequate, is it? And that's already implicit here because you're treating them not as persons. And then you're not a person if that's all you're doing.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 25:59: Just like God comes into His own in relation to humans, so we come into our own in relation to others.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin: Yes, yes yes.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum: And sometimes our finest moments are when we appreciate what is truly other in another human being and in our relation to them.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 26:27: Yes.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 26:28: And I find that to be a very profound theme. It's almost like God becomes an adult in relation to us, you know, grows into His own. That's a theme that many parents discover.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin: Yes, yes, yes, yes, yes.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum: I'm not a parent myself, but I'm an uncle, I guess.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 26:51: No, I've noticed it myself in relating to people who are parents and not parents. There's a dimension that people who've been parents tend to have that it's hard to have just on your own, without having been parents. You know, it's a very special and peculiar you might say relationship to the child.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 27:12: But that moment when you actually, a parent, actually has to make a little distance just to be properly related to their child. You know, there's an incredible scene, a moment in Buber’s I and Thou, and Buber is critiquing the Buddha, and I'm going to place aside whether or not his scholarship of Buddhism is apt, so someone else can do that, but he's quoting Buddhist scripture and he's, sort of how the universe somehow is a figment of our own mind, and in I and Though he rejects that and says no, there's a kind of a kind of separation from something we need in order to be properly related to it, and that strikes me like a really primordial, deep insight. You know, creation is a kind of condition for relating to something else properly and, of course, even in relating, using our entire being in relation to another as well, in the I-Thou relation. And I don't have that at hand, I can't whip it out in front of me, but that quote really strikes me as an important one.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 28:49: I appreciate how the affirmation of an unfinished cosmos without which we could not exercise our moral energies, the embracing of this multifaceted universe that we live in with joy and yet not seeing it as an illusion, and, of course, the necessity of becoming a self through our proper relations to others. There is something here that's instructive of how we should live our lives as human beings, you know, just writ large in the life of the Godhead, you know.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 29:26: Yeah, one of the things I ask about later, because one of the things you just mentioned, Jonathan, and you've mentioned it several times, this sort of William James conception, the need for moral struggle to kind of do something that’s not easy. You don’t just float in air. I ask at one point, well, does that mean this is sort of like if you become a Marine and they send you to training camp? They send you on all these exercises and they're tough, they test you and you learn skills by doing them. Is it like that? Is it just exercises for our development, the way that is for the soldier training? No, there's real, I'm told, there's real work to be done. The world actually needs fixing, or not fixing as if it's a mechanical problem, but it needs development, it needs movement forward and it's full of problems, and full of problems that human beings need to address. And we are God's partners, which is an awfully—that's not here so much. Maybe it's implicit already, but that's a rather noble vocation, you might say, to be God's partners and that God needs us to do certain things.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 30:51: It's very Jewish, among other traditions. Very William James.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 30:58: So, I guess you can call it post-Protestant American philosophical tradition, very Whiteheadian if you will, you know, but it's also very Tikkun Olam, repair the cosmos, humans as a co-creator with the divine. You know, very Jewish. And I appreciate that. I like how you said it's not like a gym coach to make us build the proper, I mean, although that may be part of it, but it's not the focus, it's no, it's a cosmos that needs fixing with human beings as not instruments, as partners. Yeah, and that's a profound idea and you're right, it's implicit here. It's implicit here, with a finite God evolving in an open-ended cosmos.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 31:51: Yes, exactly.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 31:54: You know it's funny because William James is a tremendous influence on Whitehead and yet Whitehead pushes the Jamesian insights into a far more systematic, pristine picture but it loses a little bit of the Jamesian wildness to it. So, I think a better comparison is with Jamesian thought he captures something more of the wild, rugged-edged nature of the cosmos and a God in development with us. But certainly, it's definitely here.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 32:30: You mentioned the Jewish tradition, which is, I think, an apt comparison, and James an apt comparison. But I also, speaking of the kind of Hindu traditions, I was guided to pray about Mahabharata, not those texts where one merges or something, finds the world's an illusion, and that's a war drama, like the Iliad, you might say. And our hero, Yudhishthira, I always just call him Yudi, likes to have these sublime thoughts and sit and talk to the holy men and so forth and speculate. And he's told look, you're supposed to be king, you have work to do, and to be nobler and more holy or elevated or cosmic than anybody else is not your job. Your job is to get your work done. And so it’s a reminder, and I take it, and I was pleased to find Iliad agrees with me. I read much later that this is a bit of a corrective to those other tendencies in Hindu thought.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 33:47: I appreciate the analysis of the Mahabharata in the God book and you know, outside of the Gita, that we've all read, I've not read the other parts of it, but you know I am very motivated to do so. My trip to the subcontinent will be this August and one thing that I love about traveling that region is that you see bits and pieces of the Mahabharata, along with the Ramayana in children's comic books in stores and out on TV, on the murals on walls, and it truly is such an important part of a whole civilization. I too appreciate something of that Ram is a warrior.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 34:37: That's the Ramayana, the Mahabharata, the Pandavas are embroiled in battle with evil brothers. I love that fact. I like how you… It's not often you see that thematized. It's not often because everyone's so busy looking at the great Hindu theologians, the Vedantins, and others that not to take– to return to the philosophical and spiritual importance of the more colorful narratives, is a great thing.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 35:14: Well, that's what I was told to go read. I'd read those other things, you know, looked at excerpts from the Vedas, which are the most authoritative, and then the 13 principal Upanishads and so forth. I was always reading the foundational text rather than the later theologians of the tradition. But then I was told, oh, go read the Mahabharata. And when I was told that I don't even think I knew Bhagavad Gita was one chapter in the extremely long Mahabharata.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 35:47: Of course, you and I, we've spoken about the Peter Brooks version and our dissatisfaction with aspects of it, but our appreciation of the things he’s trying to do.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 35:57: Well, you need to learn from each religion what it has to offer and what its limitations might be. And one other thing I was going to mention that I think would be relevant for people's lives, at least their lives as they try to think things through when God is beginning, says “I'm in the midst of Nothingness,” I say, “My logical alarm went off. And how can I make sense of this?” I ask. And God says don't worry now about making sense of it, just listen. And I'm told something similar a little later when I'm saying, oh, that doesn't make sense, you know, I say it's completely unorthodox and embarrassingly anthropomorphic. What am I to make of that? God says, “I’m not interested in what you make of it -- or in conforming My account to your prior beliefs.” And then explains why God is using literal language. That's the only way to explain the experience of being God. And I object to that. And then that's where I'm told well, that's you might call what it's like to be God. That's what experience refers to.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 37:20: Well, I'm just puzzle, puzzle, puzzled, but I think something, at least in the spiritual life, but maybe other domains as well. You know, we start out with a little thick set of categories and a thick set of beliefs and we judge everything else by what we already believe. And it's wonderful to have spiritual, intellectual openness where you're able to, well, let's just, I often think it's like encountering a strange culture or some brand new art form or style of music. I don't understand atonal music, but if you're going to ever understand it, you can't just object to it, and that would be true of any culture or new art form or new cultural form. You would have to pay attention to it sympathetically first and let it affect you.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 38:04: Yeah, I like that. I like that also. You have to soak it in, then you figure it out, and that comes later.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 38:15: You know experience, the texture of it, the flow of it, and the feel of it, and then you can analyze, you know. But you can't start with the cerebral first, and I happen to like that. I think it's something of that vivid, drama-like character which really gives the God book its power. You know the image of you looking at a fountain, the analyses of things like the Mahabharata.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 38:51: You know, this colorful chapter, this God saying to you to grow up at one point, there is a lot that's kind of lyrical. It's almost like that section of the Book of Job when God is getting dramatic with Job and you know, but these images he paints for Job are truly, I wish I knew the original Hebrew to read it in. James is majestic enough.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 39:32: There is a lot of drama here and I like that.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 39:36: Life has a lot of drama in it, at least in the view I've come to impart from, of course, these prayers, is that you're living a drama. And somebody reminded me recently Charles Dickens's David Copperfield's rather autobiographical novel. He says at the beginning I think in the first sentence I am the hero of my own story, and that's a good principle. You are living your story, not necessarily heroically I mean, that's what you would like to do but you need to make yourself– you know, you're the main character in your own story, even though that involves the interpersonal dimensions, the social dimensions, the historical and global dimensions. But still, you're living this life and living it with the divine, and it is a kind of drama.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 40:34: But also, how very apt, particularly for the God of the God book, who is a person who tells you to get more anthropomorphic, who develops, you know, perhaps something a bit more dry and abstract would do well with a pantheistic type system or in a cosmistic type system, or a Platonist or a Neoplatonic or an Advaita Vedantian picture of the cosmos, but not your God, who's a person, and yet more than a person, but also a person. You know, how apt?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 41:09: Yeah, I was thinking later about this anthropomorphic concept which is so unfamiliar and alien to our 21st century thinking. But there is that saying- man is made in the image of God. Well, I think that would rather suggest that we are somewhat theomorphic and God is somewhat anthropomorphic. We are not alien entities facing one another, but we share in some way some element of nature. Obviously, God: An Autobiography never suggests God is more anthropomorphic than what we see here. He’s not walking around. You can't make little statues of what God looks like, not like the Greek gods where you can have a pantheon and there they all are. But still, there's some shared affinity in basic nature between the human and the divine.

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum 42:07: Yeah, that's a profound notion. It's a very interesting notion. I think, believe it or not, there are certain kinds of Mormon theology that approach this.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin: Is that right?

Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum: Yeah. Which is fascinating to study in their own right. But this is a striking notion. It definitely departs a little bit from the sort of Aristotelian and Platonic flavor of so much traditional theology that we've imbibed for so many centuries, and it's a striking, striking notion.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 42:49: Well, interesting, interesting, well, interesting. Interesting. Well, thank you, Jonathan. We've probably overrun our time, but that's fine with me and I wish you well, and we'll stay in touch.

Scott Langdon 43:23: Thank you for listening to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. Subscribe for free today wherever you listen to your podcasts and hear a new episode every week. You can hear the complete dramatic adaptation of God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin by beginning with episode one of our podcast and listening through its conclusion with Episode 44. You can read the original true story in the book from which this podcast is adapted, God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher, available now at amazon.com, and always at godanautobiography.com. Pick up your own copy today. If you have any questions about this or any other episode, please email us at questions@godanautobiography.com, and experience the world from God's perspective as it was told to a philosopher. This is Scott Langdon. I'll see you next time. Thank you.