GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

121. What's On Our Mind- The Face Of God And Suffering

What are we to God? Why does God care about humans? Is God a perfect being who chooses to sit idly by while we suffer? Why is there suffering in the world?

Jerry and Scott explore the domains of reality and search for answers to suffering and what we are to God. Jerry shares a useful way to look at suffering and the subsequent growth resulting from these experiences.

Meet God beyond religion and begin your journey in tune with God.

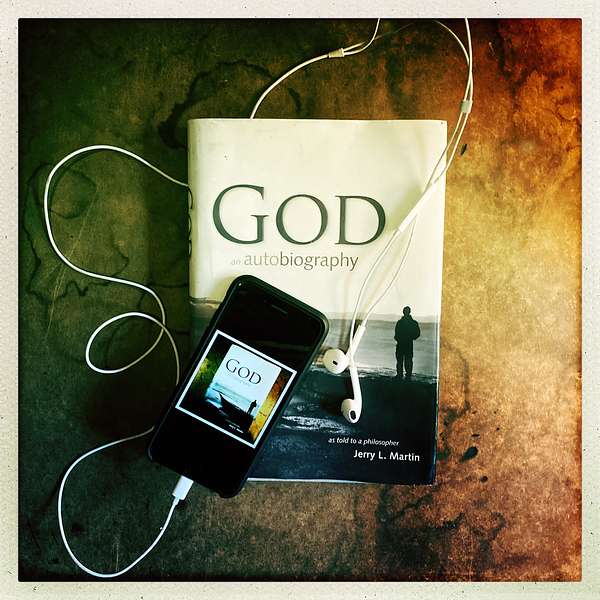

BUY THE BOOK- God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher

LISTEN TO RELEVANT EPISODES- [Dramatic Adaptation] 5. I Ask God What We Are To Him [The Life Wisdom Project] 119. The Drama of Suffering [Two Philosophers Wrestle With God: Finale] Scott Interviews Richard and Jerry: [Part 1], [Part 2] [What's On Your Mind] 120. Fear

-Share your story or experience with God-

God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher, is written by Dr. Jerry L. Martin, an agnostic philosopher who heard the voice of God and recorded their conversations.

The podcast began with the Dramatic Adaptation of the book and now has several series:

- Life Wisdom Project-How to live a wiser, happier, and more meaningful life with special guests.

- Two Philosophers Wrestle With God- sit in on a dialogue between philosophers about God and the questions we all have.

- What's On Our Mind- Connect the dots with Jerry and Scott over the most recent series episodes

- What's On Your Mind- What are readers and listeners saying? What is God saying?

WATCH- Does God Really Love Us? - Jerry L. Martin - YouTube

READ- Why am I holding back?

#whatsonourmind #godanautobiography, #experiencegod

Share Your Story | Site | Facebook | Instagram | Twitter | YouTube

Scott Langdon [00:00:17] This is God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. A dramatic adaptation and continuing discussion of the book God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin. He was a lifelong agnostic, but one day he had an occasion to pray. To his vast surprise, God answered- in words. Being a philosopher, he had a lot of questions, and God had a lot to tell him. Episode 121.

Scott Langdon [00:01:11] Welcome to episode 121 of God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. I'm Scott Langdon, and today Jerry and I return for our latest edition of What's On Our Minds. In this episode, we talk about what we are to God and how God sees every single one of us as His unique face unto the world. We also talk about the problem of suffering and why the idea of a supernatural, theistic, perfect being who sits idly by while we all go through suffering alone simply isn't the reality of this world. As always, I want to thank you for spending this time with us. I hope you enjoy the episode. Welcome back, everybody, to another episode of What's On Our Minds. And I'm here with Jerry. Jerry, I'm really excited to talk to you today about things that are on our minds and specifically stuff that has been really brewing as we've been making the last few episodes.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:02:15] Yeah, these last episodes were very striking to my mind, and especially when we revisited the episode five, is that the right number?

Scott Langdon [00:02:25] Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:02:25] Of God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. I went and looked at the text again because you can see the text online and reread it, and I think it's so very thought provoking and it's about suffering. And suffering is (a) a problem we all have and (b) a religious problem. If there is a God, why is there so much suffering? Because the world is just wall to wall with suffering. So why? Why?

Scott Langdon [00:02:54] One of the first things that you ask God in this episode is- what are we to you? And God's answer is really, really interesting. He says, "You are my face unto the world."

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:03:09] Yes.

Scott Langdon [00:03:12] What did that-- how did that feel to hear that? Like, did you expect something similar or...?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:03:17] Yeah, when I reread it, I-- we all remember the Job question that I'd forgotten the whole Job question- what is man that you make so much of him? Because it is a puzzle. And I was puzzled. You know, here I am, a philosopher, a lifelong agnostic, and I'm thinking, well, God as this eternal sort of perfect being. That's not quite the right description of God as I learn, but God seems-- why does God even need people? Why would God have any interest in the people? I don't have any interest in the weeds. You know, aren't we just weeds in the universe? Why would God be so interested? And then you read the Job question. What is man that you make so much of him? And then it goes on. I've forgotten this part that you fix your attention upon him, inspect him every morning, examine him every minute. And that's how it is. It's like your voice of conscience, which is a kind of divine voice, and it's restless. You know, any time you're going through things there's a kind of monitoring. Is this okay? Am I doing the right thing here? And so on? And oops, especially if I'm about to do the wrong thing or having temptation, that voice is constantly on duty, you might say, and God is constantly on duty. And so a lot of it was just trying to take in. The God as I encounter God is extremely personal, extremely personal. And the whole philosophical tradition and the whole tradition of high theology tends to push God away. Make God very abstract and nebulous. Because well, you don't want to be anthropomorphic, thinking God's running around on two feet, two legs, you know, sitting on a throne and this kind of thing. However, we're made in the image of God. Then we kind of, you know, we're persons. That's what we're all. We're not just two legs running around. We're whole persons. And well, we can't, if we're made in the image of God, then God is a person. Again, the philosophers and the theologians would often talk about- oh, well it's our reason. Reason is the highest part of us. And it's our reason that's the image of God. But no, it's we're whole people and there's no, although philosophers and theologians often like to privilege reason as our capacity, it's not necessarily the best thing about people. We're not smart robots going around after all. We're capable of love and duty and honor and devotion and appreciation of beauty, you know, myriad other things that are part of being persons. Well, God is a person, so that's hard to take in. And it-- and then to me, it just kind of came to pointed thing where- God's paying attention to all of this? God kind of cares what I do each day? Cares what I do when I wake up in the morning and plan my day's activities- God cares about all that? And then you mentioned they answered Scott. God says to me, that's all my thinking, but God says to me, "You were my face onto the world and onto each other." We are God's eyes and ears. But not only that, if God is going to love us, He says, it's kind of hard for God's love to be effective for us. But we can be effective in loving each other and we can express, you might say, divine love through our capacity to love. Because where do we get that? That's not just DNA. You know, our evolutionary history suggests something a lot more egocentric, but that's the divine element in us, the capacity to love each other. And God says, I need people to do it for me.

Scott Langdon [00:07:25] When I think about when I write fiction, I think about perhaps a relationship that's similar to God and me. And what I mean by that is, for example, I wrote this story called Martin about this man who lives on the Upper West Side of New York, and he's been a maitre de for 30 years at the same restaurant on the South Side down by Wall Street in New York. And when he's finished with his shift every night, he comes from the South side of New York and he takes the subway all the way back to the north side of the city. And while he's in the subway underneath, he hears a cello playing at 42nd Street where there's a big, you know, changeover place. He has to change trains and he sees this cello player who is playing this beautiful cello music. And so it's a story about the two of them and when I was writing it I hadn't thought about it this way, but after working on this project and after having this experience of God in this new way, I started to think about this again. And when I created Martin, he's really important to me, and I want to see the world the way Martin sees the world, you know? And so as Martin's story is developing, I'm right there alongside Martin. And Martin is, you know, the main character of the story. And so everyone else is a supporting character in Martin's story. But every character that shows up, there's a guy who's a doorman early on in Martin's building. And when I was writing this doorman, I got so excited about Martin and this doorman having this conversation and watching the scene play out. And what does this guy do after he's not the doorman anymore? I don't know. Maybe we'll explore him another time. But now it's Martin's story, right? And it's sort of that way in our lives in the sense that we are the hero or the main character of our own story. And everyone else who comes in, in whatever way, are these supporting players and whatever. And yet God is writing all of them. And I got a taste, just a little smidgen of what it feels like to create a person. If you ask me who Martin Blum is, I'll tell you exactly who he is. Even if I tell you that Scott Friedman exists, you'd go, "Oh, okay. I believe he exists, too." Now, Scott Friedman, quote unquote, is a real person. He's my best friend. But Martin Blum is somebody I made up, but he's also a real person in the sense you don't know because you've never met Scott, You've never seen Scott, and you've also never seen Martin Right. But to me, both of these creatures, if you will, are completely and fully real. And I'm invested in Martin almost in the sense as much as I am in my best friend, Scott. Does that make sense?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:10:19] Yeah, yeah, yeah. I mean, why is it that when-- who is it who dies in Little Women, Beth or something? Everybody cries. Well why do you cry. Well, that's because you have come to love Beth. The other little women love Beth. And yeah, I've been very struck by that same phenomenon. One cries at movies all the time. I tear up, you know. And in movies, of course, there's a person moving on the screen. But you cry in fiction, you can cry over historical characters if it's somebody you come to care a lot about in their historical story. And the fictional characters of the historical characters, just as you describe it, are real in kind of the same way you might say. This is the art of writing, is you create a person when you write and I've seen novelists say, you know, I plan for the character to do such and such, but once I've created this person, that isn't what that person would do. So, I had to redo the plot. Follow what this character does.

Scott Langdon [00:11:34] And it's almost like the character is telling the writer, this is not it in a similar way that, you know, we have talked about human beings arguing with God in that sense. You know, like, "God. Are you sure that this is what You want?" And God saying, "You know what? Okay, I know. I see we should go in this direction," or whatever, that there is an input in a very similar way from a fictional character to the writer as there is from us to God. I think there's a correlation there.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:12:04] Yeah. Yeah. That is of course, what Abraham does. You know, God's the big boss. God can write them all out if God wants to. Abraham, who followed God unquestioningly in taking Isaac off to the mountain, Abraham says, "Wait a minute, are you sure this is what You want to do? Aren't You God? Aren't You the standard and guarantor of justice? And is this compatible with who You are?" And that arises for the novelist. And God says, "Yeah, I think you're right." And they negotiate over it. So, yeah, that's all quite true, and it's part of the puzzle of how to live with God, because God is somewhere in between the real person and the fictional person. God is real, but you don't get to sit with Him in your living room. You don't get to do that with God. And so you have to relate to God through one's sense of God's presence and God's character. And religions help structure that, they give you the stories that bring it to life- the events that are both historical and semi-fictional that all bring it to life. They make God available to a person in their interactions with the Divine.

Scott Langdon [00:14:07] I want to ask you a quick question about a word that has been coming up in my study outside of this work, but also in this work. And it's the word real.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:14:18] Real.

Scott Langdon [00:14:18] We talk about what is real. I'm not really comfortable with that language because I think there's something more to the definition of what real is. But I pause on it and I contemplate it because I think a lot of the time what the discussion is about is what is the essential nature of us? If you go back and back and back and back, you know, when we're gone, what is there? When Scott Langdon is dead, what is there still? and we've talked about this- the separate and sameness that we are ultimately, the essential nature of us, is God. All things are God. So when I talk about what’s real and I think you say this too, it's being in the world is real. So when I watch a movie, but I come back to this reality, I go to sleep at night, I wake up back into this reality, I daydream. Yeah, that's another reality, another plane, if you want to call it that or whatever. But when I snap out of it, quote unquote, I'm back to what is real. How do you talk about it?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:15:21] Yeah, the quote from the God book that comes to my mind is God says if it's a mirage, it's one you can drink water from.

Scott Langdon [00:15:33] Right. Right.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:15:36] And a lot of that is I tried to pay closer attention. A very– the Buddhists, for example, have this very specific definition of real. And it's real means self-sustaining existence. Something like that. Self perpetuating what they think a Western concept of substance is- something that just goes of itself as a completely independent standing. And they believe everything is what they call codependent rising. You know, everything is depending on everything else. And so they'll often say, if you fuze them, "Do you think it's all illusory?" They'll say, "No, it's not that. You know, it's just to accept the world as it is. And the world as it is does not have that self-sustaining substantiality to it. And that's okay. It's still real. You still drink water and you still want to rescue the child from the bottom of a well they dropped into. That's perfectly real in that sense. But it's just not completely independent in some what they take to be Western sense and that they take to be not quite accurate. Just not accurate to how things really are. But I'm more comfortable with the Western myself and I don't think quite as the implications they see it as having. But there we are. You know there are different ways of conceptualizing the world and of seeing it. And what I think one of the great confusions of an awful lot of discussion is precisely on what you're putting your finger on. Well, what do we mean by real? And often, people who want to say this, that and the other thing aren't real, have a very specific idea of real. And the other things don't match their idea. The material is tradition. And we have materialists among us, people with this instinct. The only thing real is, you know, my fist. You know, this is a solid object, a physical object, and anything else is unreal. And yet, you know, I used to have a colleague in Boulder who would ask of any visiting speaker if he could work it in, if it was relevant enough, are numbers real? Well, that's kind of puzzling. You know, you can't put them, oh, the number of five in your hand, you can't. You don't bump into it in the dark. And yet it's kind of funny to say, no, no, it's just made up because things are certainly countable and there can be more things or fewer things in the room and so on. And, you know, there are all these other kinds of reality. This is gravity real? Gravity isn't a thing. And yet there it is, these forces. Are they real? People worry about whether quirks are real? Well, they're not-- you don't bump into them in the dark again. They aren't real in that sense. And moral qualities, good and evil, are those real? Well, my view is a kind of ontological generosity. All these things have their own domains within which it's correct to call them real, and they have--The only mistake would be how to confuse domains of thinking that numbers are like pieces of furniture. No, they aren't that. But that doesn't mean they're not real. You've got to realize what the domain you're working in. And you can actually determine truths about numbers and truths about good and evil and truths about abstract entities of a certain level of physics where you don't know, are we still talking about reality? You know, it's gotten so odd. Yeah. Just just relax and accept that there are different types of reality. And the main thing is to pay attention to each one so that you understand with some clarity what it is you're talking about.

Scott Langdon [00:19:49] It seems like there are two things that we're talking about here in a sense. One has to do with what we agree about. Or a construct, can we call it construct? So, numbers, right. So, if I say four, you know what I mean by four. Abigail knows what I mean by four, and anybody, you know, come to an-- we agreed on it. Right? Even though we don't have a thing you can touch, then there are other things that aren't constructs of ours, humans. Laws like you mentioned, the law of gravity, it's nothing we made up. But if you step out a two storey window, you're going to fall to the ground. That's the way it goes, right? We talk about suffering in this episode, God says "Suffering is the law of growth in the universe," and he talks about it like ripping muscles. You know, if you're a bodybuilder and you're weightlifting, the muscles are tearing and they build back up all of these different things in nature about how, you know, you've got to break down and then build up stronger the way bones heal, so forth. When we deal with suffering, it seems like we want to say, "How do I feel better?" You know, when I get suffering toward me, how do I move this suffering away and feel better instead of how do I encounter the suffering and deal with the root of the suffering? And so when I think of suffering as the law of growth, that's tricky and hard to digest, I think.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [00:21:28] Well, there's a tendency that's been strong in theological traditions, East and West, to want to make suffering go away, to want to make it into non-suffering. Either make an illusion, that's one way you can go, so it's not really suffering. Sit on a hot fire. So what? I don't know. But there's a Western version of that, which is, every suffering is in some way for a greater good. And that just that's repeatedly rejected in God: An Autobiography, in my dialogues with God. God says suffering is really, really bad, and it's just as bad as those who reject God because of it, think it is. So He's not downgrading or belittling that or saying, no, it's an optical illusion for some other ultimate divine grace. And those explanations always, to my mind, smack of some element of bad faith. You know, you can find in life it's true that you can find many times where something going wrong produced a greater good. And so, you know, one clings to those because that is an important aspect of human experience. Sometimes things that look bad at the moment do turn out to have some surprising benefits or things turn out better because of them. But I can never see that as accounting for the infant who burns to death in a hotel fire. There's no possible greater good and to say some greater good sometimes that's answered through an afterlife. Well, that doesn't answer it. I mean, it's still just a horror. And yet you get to an afterlife some better way than being burned up, burned to a crisp. So, those, trying to cherry pick examples, and it's important to keep in mind those examples, and I was thinking today about the experience of two people who have experienced the Holocaust, which is about the worst thing, socially, a collective phenomenon, one can point to. That is a form of being burned to a crisp after all. And one is Elie Wiesel, who wrote this famous memoir about the death camps. He was there, and the insights that came to the world. Well, that doesn't-- you wouldn't say let's have a Holocaust so that Elie Wiesel can write this great book. Nevertheless, something he did and we have to recognize as part of the scheme of things is it enabled him to give us all a level of insight into human phenomena, human nature, human evil that we would not otherwise have. The other example I was thinking of is Viktor Frankl, who wrote Man's Search for Meaning. He was in the camps and he noticed some people handled it better than others. Some people succeeded and in fact survived. What trait do the survivors share? They were people who had some meaning in their lives, and Man's Search for Meaning is one of the world's biggest sellers ever, it's a deep insight into the nature of life. And if you come back to suffering, a question about any given suffering, I don't think this makes them all okay. Viktor Frankl certainly would not have said, the Holocaust was worth it for my great book. And he started psychological clinics, help people find meaning in their lives and so forth. Okay, that was wonderful. That doesn't justify the Holocaust or make it on that benefit. Nevertheless, that is, you might say, part of the meaning of the Holocaust that it has. We can learn things about human nature that are in fact not just insights into human nature, insights to a fundamentally important phenomenon, but they help us live better to appreciate the meaning in our lives, and make the most of that. And so one thing to ask about any suffering is is there meaning in it? I sometimes remember when I first got to know Abigail and she shared her story one Saturday I went up. We spent the day she shared her story with me. The next Saturday I went. She asked me questions about my story and a crucial part of my story, I mention it in God: An Autobiography, the great, main tragic event of my life was the death of my baby brother and not the shock of death, but the impact it had on my mother, who already tended to be, she had some wonderful qualities, but tended to be, she lacked empathy, was egocentric. Everything was about her projects. And this also threw her into a downward spiral. She cried every day and I would come home and find her stretched across the bed crying, and I would pat her on the back. "Don't cry, Mommy." And I just suffered greatly from that for many years. And a doctor at one point, I had these malfunctions, you know, and she asked the school doctor, I was in fifth grade, and she said I've got these problems. And he said, "Any bad thing happened in your life like your husband lose a job or something?" "No, no. Well, I lost a child." "Does he ever see you cry?" "Yeah. Every day." "Don't let him see you cry anymore." She stopped it. I stopped having the dysfunction. Bang! Bang. But when I told that story to Abigail, she asked this interesting question. I gave a kind of psychological analysis that she asked the question, "What did you learn from that experience that you would not have learned otherwise?" And the answer immediately came to my mind. Her answer was, "I think you're very sensitive to women." And it is true, you know, it made me very sensitive to my mother's suffering, even though that suffering was causing me pain. I became acutely aware of it, sensitive to it. I could tell when she was suffering, and that was Abigail's answer. But the words that came to my mind immediately was, I learned to love Abigail. Well, that's just the concrete instance of Abigail's explanation. So that's not the only way to look to an experience of suffering, but it's a useful way. What does this experience tell me? And that's another form of what meaning, what meaning did that suffering have? Because the meaning is what you articulate when you say what it taught you.

Scott Langdon [00:29:11] Thank you for listening to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. Subscribe for free today wherever you listen to your podcasts and hear a new episode every week. You can hear the complete dramatic adaptation of God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin by beginning with episode one of our podcast and listening through its conclusion with Episode 44. You can read the original true story in the book from which this podcast is adapted, God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher, available now at amazon.com, and always at godanautobiography.com. Pick up your own copy today. If you have any questions about this or any other episode, please email us at questions@godanautobiography.com, and experience the world from God's perspective as it was told to a philosopher. This is Scott Langdon. I'll see you next time.