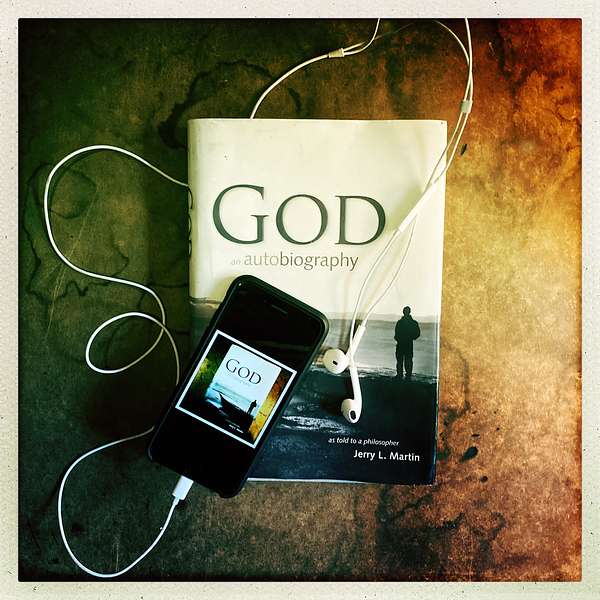

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

198. What's On Our Mind- Awakening to the Aesthetic: Prayer and Cosmic Connection

Curious how aligning your desires with a higher will can transform your spiritual practice? In this What's On Our Mind, Scott and Jerry explore God-centered prayer, intention, and spiritual growth, contrast spontaneous and memorized prayers, and explore ancient Chinese spiritual traditions, offering practical insights to deepen your connection with the divine.

Follow along with future episodes and get your copy of God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher here. Get the newest book, Two Philosophers Wrestle with God- A Dialogue here.

Relevant Episodes:

- [What's On Your Mind] Embracing Divine Callings and Personal Courage in Your Spiritual Journey

- [Life Wisdom Project] Aesthetics and Philosophy in Chinese Spirituality | Special Guest: Dr. Jonathan Weidenbaum

- [Special Episode] God Shares His Earliest Interactions In Chinese Spirituality

- [From God to Jerry to You] How To Pray

Other Series:

The podcast began with the Dramatic Adaptation of the book and now has several series:

- Life Wisdom Project: How to live a wiser, happier, and more meaningful life with special guests.

- From God To Jerry To You: Calling for the attention of spiritual seekers everywhere, featuring breakthroughs, pathways, and illuminations.

- Two Philosophers Wrestle With God: Sit in on a dialogue between philosophers about God and the questions we all have.

- What's On Our Mind- Connect the dots with Jerry and Scott over the most recent series of episodes.

- What's On Your Mind: What are readers and listeners saying? What is God saying?

Resources:

#whatsonourmind #godanautobiography #experiencegod

Would you like to be featured on the show or have questions about spirituality or divine communication?

Share Your Story | Site | Facebook | Instagram | Twitter | YouTube

Scott Langdon 00:17: This is God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. A dramatic adaptation and continuing discussion of the book God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin. He was a lifelong agnostic, but one day he had an occasion to pray. To his vast surprise, God answered- in words. Being a philosopher, he had a lot of questions, and God had a lot to tell him. Episode 198 Welcome to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. I'm your host, Scott Langdon, and this week I return with Jerry Martin for our series What's On Our Mind. Our conversation this time centers around prayer and being in tune with God and what that might look like to us individually in our daily lives, and we also talk about what the early Chinese people brought out in God, what God discovered about God's self, you might say, through early interactions with the Chinese.

Scott Langdon 01:38: Humanity's development and God's development are inextricably linked, and the ancient Chinese understood this in a completely new way. But what does all of that mean now to us, in our modern-day world?

Scott Langdon 01:52: Is there anything to be gained by seeking to be in tune with the divine hum of the universe. Here's what's on our mind. I hope you enjoy the episode.

Scott Langdon 02:11: Welcome back everyone to another edition of What's On Our Mind. I'm Scott Langdon and I'm here, as always, with Jerry Martin. It's really great to see you and talk with you again, Jerry.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 02:19: Well, good to see you, Scott, and I think we have some interesting materials from these most recent episodes that have run so a lot to talk about today.

Scott Langdon 02:29: Yeah, I'm really excited about this one. This one is– this episode covers the unit where we were centered around episode 20. That's the Life Wisdom Project episode, with Jonathan Weidenbaum this time examining episode 20. And that was where God leads you to the Chinese mind and God talks to you about how God was working with that ancient people and how they came to Him, which was really fascinating and I want to get into that in a few minutes. But we started out this unit with episode 193. From God To Jerry To You episode in that series, and in that episode you talked about prayer and laid out basically four points that you focus on as you desire to get in tune with God. And I want to kind of quote that prayer as you talk about it in the episode. You say this is what the prayer is like for you. You say,”Llord, please help me to have the desire and the understanding and the strength and the courage to do Thy will. Thank you, Lord.” That's a wonderful, just sort of straightforward prayer that focuses on these four things.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 03:56: Yeah, the key, of course, is in the last phrase to do Thy will. And it's what I call God-centered prayer because of that. That's the aim is to do Thy will, and these are the elements needed if you're going to do God's will. And the first of all, and in some ways the hardest for people, is the desire to do God's will.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 04:21: Most prayer is asking God to do our will, and that's what I mean about the different, that sort of human-centered prayer. You know, me-centered prayer. If you will, God, help me with this or that or the other thing, or help the person I care about. But we're shifting the focus to do God's will and there are a lot of obstacles. Ego is one of them, but also just the distractions of life. Each day I have a to-do list, I'm running around busy. So even to think that's my will. Now, even to think about what's God's will, and to think of that not once a week, on Sunday or something, but to think about it during the day and ideally to kind of hold it in the back of your mind the way you're aware there's gravity all the time even though you're not explicitly thinking about gravity to have it kind of in your frame or your orientation of yourself and sense of life that you're trying to be in sync with the divine, in cooperation with, in harmony with whatever you can put that in different ways.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 05:25: But that's what you're trying to trying to do. You're trying to keep, like the people have to get sea legs when they go to sea, you're trying to get your God legs, you know, so that through the course of the day you're kind of in harmony with the divine.

Scott Langdon 05:48: What I liked about it and what I examined in it about myself and my struggles throughout my life with prayer and what they were like when I examined your prayer here, this quote, and those four things that came out desire, understanding, strength, courage again all focused around doing Thy will, doing the Lord's will, but that structure, those things, I liked the simplicity of the structure and I was reminded of my journey and we talk about this a few times, but when I was very little, you know, seven, eight years old, in the Lutheran tradition and felt naturally in sync with God in the woods or in church itself or hearing music, just didn't think of it, just always kind of felt this connectedness. In that tradition was praying, and this is the Lutheran tradition, was often in the worship service, praying by rote or praying in response, and it would be written out in the program that you would get on the way in right and you sit down, and so the minister would say a line and you're looking at it in the program and their lines, your lines are high lit, and so you say the bold lines you know. So we'll say peace, be with you. And we say and also with you. And then we say let us pray and then we all pray this prayer that's in the thing and that to me was just sort of the natural extension and the problem would come up hey, you know what if you just say it by rote? You know, here's the words you should pray, but then you just pray them without meaning. And my grandfather, my maternal grandfather, made it clear to me he wasn't a very religious person in terms of participating religiously, going every week Sundays, in fact he didn't often, but had a very genuine heart and made it clear to me and to my mom before me, when you say these prayers, let's say the Lord's Prayer, our Father who art in heaven, and you kind of go through it, examine it, what are the words you're saying, mean the words that you're saying and make it a real thing. So in a sense he was giving me my first acting lessons, in a way of taking lines and what do they really mean and what do you mean when you say them. So I got this sense that you could do that and should do that.

Scott Langdon 08:21: But when we moved to a more evangelical tradition when I was 13, the tradition there said anything by rote like that is a bad idea and not a good thing. Instead, everything should be like a conversation and right off the cuff, and it's this personal God you can just talk to anytime. The problem with that became even in a worship service the leaders of a congregational prayer would just sort of wander and say things on behalf of the congregation oh, I'm not sure that was on my heart, but okay, you can mention that on behalf of me, I guess and it would wander, I guess, because we didn't have anything formulated.

Scott Langdon 09:06: But then in my own personal prayers that became a problem too, because then I would not have anything structured and would wander off and my mind would get distracted, because that's how my mind works. And then I would beat myself up for wandering. Oh, if I were a better Christian or a better person, I would be able to stay more concentrated, and you know that's, I'd fall asleep while praying. Oh, that's a bad. I didn't say in Jesus' name, amen, I forgot that part, and now it's null and void, like all of these things that came with this sort of new baggage.

Scott Langdon 09:40: And so I had this real struggle with, oh, the structured prayer, but then the non-structured prayer. I wander, oh, I'm just not good at prayer, but when I saw your prayer and how simple it was and what those sort of steps seemed like, it seemed more than a structure. It seemed like, hey, this is a marriage of maybe both of these things. It's a pathway that I can explore within this structure, which is much like a piece of music or a piece of Baroque music, where you're going to explore, but within these boundaries of harmony and such that kind of thing.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 10:23: Well, that's very interesting, Scott, and I like it the way you brought that out. These are both valid ways of praying and I think one of the problems in general in our history of religions religions in the plural is that they're always arguing over which one is right. There's one right way to pray. In the early Christian church in Britain, the Irish had somehow, the Welsh had somehow developed the idea of Saturday as the Sabbath, which seems literally correct, but the other Christians literally correct, but the other Christians Sunday had become the Sabbath, and they almost went to war over which day is the Sabbath. And well, okay, one can do that, but God's a bit bigger than those issues and God is perfectly open to our contact by whatever means works for us.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 11:30: So if we have a memorized prayer and we say it, I think you're right, Scott, you've got to say it with meaning. You can't just run through the words. You've got to say it with meaning because you have to be present to your own prayer and in general in life, we need to mean the words that come out of our mouth, and that is never truer than in prayer. But at the same time, I grew up in the tradition, a Baptist tradition, and I left behind a lot of the doctrines, but I kept that mode of prayer, seemed natural to me. And so when I'm praying for guidance or praying to giving thanks, it's a perfectly spontaneous I don't know that I other than Lord's Prayer or something, if I knew any memorized prayers, any standard prayers.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 12:21: But the different things work for different people and part of the challenge of being human is to find out. Okay, how can you best pray in general? How can you best connect to God or to the divine in some more amorphous, less personalized sense? How can you do that in your life and do it with success and fullness?

Scott Langdon 12:54: One of the things that came through to me early when my grandfather was talking about saying, let's say, the Lord's Prayer I know that was one of the prayers that we learned by rote, the 23rd Psalm, another, you know, don't just memorize them, look at them, analyze them, talk about them, ask questions, you know, really dig into what it is that you're saying. And what I didn't realize at the time was that that would be a lifelong pursuit. You could just work on that, work on your lines if you will all your life and find something new in the Lord's prayer all the time, for example in the 23rd Psalm, you can just keep coming back to it and finding something new, with that mindset of curiosity and adventure about getting into text. But what my grandfather was talking about back then even was this, as I mentioned earlier, this link between religion or my, let me say my relationship to God and through the religious experience of Christianity for me and theater and being an actor, and that working with text in that way and the desire to really know and be truthful in a moment carries itself forward, not just to the art of what I do, but into life because of what you mentioned earlier, like you want to really make sure that every word you say when you're talking to somebody is what you, what you really mean. You know what you intend.

Scott Langdon 14:40: I heard a great phrase. My best friend introduced a phrase to me many years ago that I keep working with and I'm not sure where he got it from. I mean, he got it from a friend of his, but I'm not sure of its origin. But it goes like this: the meaning of your communication is the response you get, regardless of your intention. And I thought, hmm, that's really interesting, because we do a lot of things, like you know, we say something and somebody takes it the wrong way. Right, we go oh that's not what I meant, and well, that's not what you intended, but that's what that, that's how that person took it, that's how they meant it, and so you kind of you realize you're responsible for your communication on both sides.

Scott Langdon 15:21: If I have an intention and I can see by your response that it's not landing the way I had intended, it would, maybe you misunderstand me. Maybe I have to try to work with that a different way so that we can have that connection. When I think about it that way, I think about much more is involved in prayer than asking for something. It's when I'm asking God about something, when I'm talking to God about something, and I'm really sort of choosing my words, and often prayer is just this conversation, but it's a conversation with intention. It's a conversation about things that mean something, even if it's just oh, this is a wonderful day, or whatever I want to communicate beyond me, and it's not just a one-sided thing. I guess is what I'm getting at. The idea of practicing prayer isn't just making our ego better, but it's the relationship between God and us. If God is continually developing, then the conversations that we have in prayer go both ways.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 16:32: Yeah, I was told that explicitly at some point. I think it was in the context of love. Love someone, you know, it really is a truncated thing if they don't love you back. And I suppose a lot of our loving behavior has the challenge that you're talking about. You can say to someone you can intend to give your wife a compliment and saying, well, your hair looks better now. And she's thinking, uh-oh, I've looked horrible before before. But that's a failed compliment, right? A failed communication. You didn't quite communicate what you were trying to communicate, and an awful lot of life consists of trying to get the point across, trying to communicate, and that means not just the content but the feeling that you're trying to express.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 17:31: And in prayer there would be that challenge, and we trust that God can discern our intention.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 17:43: But God is also developing, and so we need to say and I'm always struck that Exodus begins with the people of Israel cried out, who were in bondage in Egypt. They cried out and God heard their prayers, and that almost is how the whole story gets started, apart from Genesis and Abraham and all, but here is the rest of the story starts with Exodus and it goes on from there, from what God does when He hears their prayers, and then it's a back and forth. After that, both God and Moses and the people of Israel are all interacting with one another through the whole story and kind of that fits my sense of life that we're always interacting through the whole story. God and me and my wife and you, Scott, and members of our great team that puts on this podcast series. God's working with all of us and we're working with one another and with God, and so some melange or whatever the word would be, and that's how things happen.

Scott Langdon 19:35: This unit was centered around 20.God Shares His Earliest Interactions In Chinese Spirituality and something really interesting happens here that I hadn't thought about in this way until working with this episode. God explains to you that the Chinese approached Him and it was the Chinese responding to nature in a particular way that gave God a new sense of God's developing identity or character, and I thought it was really interesting that this was a revelation to God in a sense that they approached Him. I thought it was important. He felt it was important to tell you that and talk about it in that way. Can you talk about that?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 20:22: Yeah, the Chinese. There's a longer story, of course, but the gist of it is that the Chinese saw the divine in a different way. It's not like the God of Israel speaking up, it's not like Jesus coming and that whole story. It's quite different from that. The Chinese responded to sort of cosmic nature, the design of Capital N. We're not talking about a picnic in the woods, we're talking about the overarching cosmos. And what they noticed was it's beautiful, it's beautiful, it's amazing, it's full of harmony. They saw the harmony in that overarching frame of the universe and God for the first time realizes oh, I am sort of harmony, aren't I? And these words that come out, some of them are musical, and the divine metronome, that kind of thing. I'm kind of the measure and standard of beauty, harmony, order, tranquility, all these things sort of combined. And they're noticing that and they have an exceedingly fine appreciation of that. It's not just a generic oh God's beautiful, but it's spelled out in particular locations that have their own distinctive character.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 21:54: So there are whole theories of place and where things should be, where they should be in relation to each other to be harmonious, and how you live your life, you live your personal relationships in a way that is harmonious. So there's a theory of the social order that comes out in Confucius, for example, and in Taoism it's more the sense there's an underlying reality to things. And you don't need to go fix it. It's very different from certain Western views. You don't need to go fix it. Water finds where it's supposed to be and it sits there still undisturbed. A lot of reality is simply like that and you just go with it. You just go with it. Well, Confucius says you also have social structures and you have to arrange those harmoniously. And that is a little he believes does take personal self-cultivation, not just being. You know, but both are true and those come out in these episodes 20, 21, I think of Life Wisdom, they're discussed.

Scott Langdon 23:19: Yeah, one of the things upon reflection of this way of seeing the world not against or versus how I saw the world, but in contrast, I think, to the way I was raised there was an underlying sense the whole time, and not just in one of the ways of the tradition over the other, both in the Lutheran and the more evangelical tradition, sort of all of Christianity, had the overlying or maybe underlying sense that we are broken to begin with just simply by getting here, by being here. But we're in the wrong place, and you mentioned it earlier. With this other way of seeing things, there's an underlying sense of things and you don't have to fix it. It's about getting in tune with it, getting in flow with it, going with that and when you, you know, I talk about the moving sidewalk in an airport often as an analogy you could turn around and certainly walk against it, but you know that the flow is going this way, that the flow is going this way and starting out with a sense that you're flawed to begin with, I still I think I'm recovering from that because that was not the earliest sense, even within the tradition itself, hearing the language, you know you're broken and here is the way to get fixed and this is what was done for you and you have to accept it and all of those things, even with that sort of structure there, upon reflection, I realized that the most peaceful times were more like the way we're describing in the Chinese mind, where I would be say, at summer camp, on a mountain, looking out, going, ah, this is amazing. Or seeing a play and feeling this connection between the audience and the players, or hearing a piece of music and going, ah, yes, those were the times that I was most connected, even within the structure that would say you need to do this, that or the other thing and fix it. I had that anxiety to have to fix it. But in both of these traditions the Chinese tradition and at the heart of the Christian faith, is this being in tune, being in flow. We talk about it as being in tune with God.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 25:47: Yeah, and in the very personal tradition of the Judeo-Christian and, I guess, Muslims, I know less about that tradition, but anyway, what you're trying to do is to conform your actions to divine will, divine purpose, and there is a drama in life. I mean that's part of the benefit, I think, of this sort of more Western approach. You can be moving forward or backward or you know whatever, and life is a challenge, not just to sit in a closet, you might say, humming to yourself. But this Chinese tradition, it's not like that.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 26:37: I kept being puzzled as I was first looking at it, because I was looking for who's the founder of this. That was my idea of a religion. It has a founder, and I couldn't find a founder. I found oracle bones, but they were quite a different thing.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 26:52: And I noticed the books on Chinese religiosity always talked about things like the Chinese mind. It's more like an attitude. Not just an attitude I mean, that sounds kind of superficial but a whole life orientation, a whole life orientation that then permeates thought and sensibility and everything else that is toward this sort of cosmic nature, articulated in different ways by the different traditions, but one in which that's what God talks about to me is the aestheticizing of nature, that they see it as aesthetic. And a crucial concept that's, I guess, been brought out in Western aesthetics, maybe came to me somewhat independently is the key concept in the aesthetic is the willing suspension of desire. They talk about drama as requiring the willing suspension of disbelief. You know you've got, for the moment, believe all this is happening. You know and you're seeing it happen. Here we're talking about the willing suspension of desire and it's very much like the first step of prayer. You gotta have the desire to do God's will.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 28:16: In my version of, you know, prayer to a personal God, but here it's the same challenge to appreciate the aesthetic, the beauty, the harmony of nature and to put yourself in relation to that. You have to suspend desire in the sense of seeing things only for your use. What is our attitude to nature? It's primarily a resource for our exploitation, right, and that's one reason we have environmental crises and so forth. We're always somewhat trashing nature because we want lumber for our houses and so on and so forth. But that kind of desire, that grasping desire, a lot of which is necessary for life, obviously, but nevertheless there's more to our relation to our cosmic environment than that, and that more involves this deep appreciation.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 29:19: Martin Buber talks about saying I/Thou to nature. So even though you don't have a personal partner in that you speak to nature with the same respect. You might say that you'd speak to a person, and that requires some setting the same sort of thing as good prayer. You have to set aside ego, you have to set aside distractions. You have to set aside who knows what else the clutter I often just call it the clutter in your life. You have to step back from that and just take nature, capital N in, and try to orient yourself in concert with it.

Scott Langdon 30:10: This sounds like the prevailing view of so many people that I work with and know in the world today that have come from one of two places, broadly let's just say, and those two places would be a religious tradition that they were introduced to by their parents when they were born and got to a place where they have rejected it or have been raised without any religious tradition at all. You know their parents had rejected it before that and so they just weren't, but they are, and they would probably fall into the spiritual but not religious category, the SBNRs. Right, and when you talk about prayer and the thing that really changed for you, being an agnostic to a believer, is a word we would use now, I guess was this notion of a personal God was not important to you before, but then after the encounter with God, there is, God, is clearly shown God's self to you in this personal way. I am a personal God and it was a response to love. It was a response to something so God could argue, just like he does with the Chinese to you, that you approached Him right. You responded to something so you had love, and it was this natural response to be grateful, number one. And then number two, this desire to be of service. To what, to whom? It didn't matter at the time. It's just to be of service, right? So there was this response to God.

Scott Langdon 32:10: So my question to you here is If you are someone who can't work with this idea of a personal God because of a religious experience that went wrong or bad, or you just don't really have a faith background to grab onto at all, what would prayer be like? What would that mean? It's more than meditation, although meditation is what's being often talked about today. Science-wise, we know meditation does the things that take care of your body and your mind and your spirit and seem to be and are ways to connect with the beyond us. But what would prayer look like for somebody like that?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 32:51: That's a good question, Scott. I'm not sure you have to have prayer in this formal sense that we've been talking about, or it's informal substitution, a conversation with God, for example. But I think you have the same four elements that were present in my discussion of prayer. You have to have the desire, and we've already talked about that. You can't relate even to the beauty of reality without setting aside grasping particular concerns. I don't mean to say they're all bad, they're just part of daily life. But anyway, if you just think of nothing but how to get to work and how to get home and how to put breakfast on the table and blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, well, you're never going to rise to any larger appreciation In our Wonderful Life Wisdom episode Jonathan Weidenbaum told a Chinese story about a guy who's a thief, who breaks in and steals the priest's robe right off his body, but the priest kind of lets him. Oh, you want my robe here, you know, okay. And then the priest, who'd been contemplating the moon, says ah, I wish I could give you the moon too, not just my clothes. But of course he can't give it to the thief. At Jonathan's point the thief is just a thief. He'll never be anything but a thief. He looks around, all he sees are things to steal. And if he were to raise his eyes you might say he would say oh, there's more to life, there's more to the world, there's a whole ideal realm. And it's a beautiful realm, like the way the moon is beautiful. You just swoon over a beautiful moon. But the thief hasn't risen to that level. And what the thief completely seems to lack is the desire to rise to another level. And the key element here is that desire. And you notice, in my prayer I don't ask for the desire to be given to me, I ask for help because even here, even I believe in a Chinese mode you're going to have to do something. You can't just drift along in life and expect to appreciate the deepest aspects of reality, so you have to work with it. But you ask for help because in Eastern tradition doesn't use the concept of grace, but they have something very analogous to it. Somehow you have to have a benign nature that's going to kind of help your efforts, lend itself to your efforts. Then that second point is understanding. Understanding comes in in personal prayer, because if you're going to do God's will, you need to know what it is. So let me know Thy will, and that's situational.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 36:08: One of the nice things I think of the discussion with Jonathan Weidenbaum was we talked very much about attentiveness to the nuances of context. He discussed when he had this tragic thing of getting married finally and then she died within about a year she died. Some sudden thing, rapid zoom, she's gone. The family is there. It was time to stop support and yet he says the family, the parents weren't yet ready. People were advising that. He thought she would have agreed with it had she, you know, been part of the discussion, but the parents weren't ready and he felt he had to take that into account.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 36:56: That's one of the nuances of the situation. So you pay attention to all these and notice none of that requires it would be very Chinese, but none of it requires God as a person. But it does require some sense that there's a kind of order here that one should be respecting, and the order includes the feelings of the people and their relationships to one another, their histories and so forth. You have to pay attention to all of that and that's how you come to an understanding of what let's just call it for short the cosmic harmony requires. You have to kind of discover what the cosmic harmony requires, and it's not just that there's one big formula or something like E equals MC squared, the spiritual version of Einstein's formula, but it's nuanced and situational and so, like much of art, you know, each thing is different, each situation is different. So you have to have an appreciation attuned to the particular situation.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 38:04: And that's why I often think of the analogy I've been given in prayer of an instrumental group where the musicians jazz or otherwise I've heard it in a kind of country western mode in visiting Nashville but they play off each other in a way that not being a musician looks kind of amazing to me. How do they know when it's time to come in or even to do your own riff, you know, and so on, or take it in a slightly different way. Some other people will then pick up on that way. That all seems amazing to me, but it's a pretty good analogy for how life really is. You got a harmony in the sense of musical quality going on, musical values being achieved, and yet it's spontaneous. It's probably so intuitive or something ingrained practiced from being a good musician, that it would be hard even to articulate. Oh, this is why I did this at this point. You're certainly not thinking about it, probably normally in advance. It just comes to you oh time to chime in this way or take it off that way.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 39:14: And a lot of life is that, paying attention to the particulars, and that itself, in the Chinese form, has a kind of aesthetic coloration. There's a slow motion film of an artist where we're watching his paintbrush. You know, and you watch them. The artist just seems to be going almost randomly, swoop, swoop. You know, stroke here, stroke there. The slow motion film shows the hand. It's as if the hand is making many decisions, going through indecision this way, that way, many adjustments, and then finally the stroke here. And so a lot of life is like that. It's aesthetic, but it's very particular, very detailed.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 40:00: How do you know when to speak and when to be silent, when to speak at a funeral, or whether or not to speak at a funeral, or a wedding, or the retirement party, or someone's leaving for another job? What do you say? Do you speak, do you not speak? And all of that is something Confucius writes about, about when you should speak, about the way, which is the word the Confucians and the Taoists have in common, and it's the right way, the right flow. He said to speak to a man who cannot, not prepared to listen about the way, is to waste words. To fail to speak to someone who is ready is to waste a man or a person, we would say, is to waste a person.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 40:56: And so, anyway, all of those are nuanced decisions and we learned how to do them, you know, by paying careful attention to how we're living and we pay attention to the moon, you know, to the ideals and the sense of overall harmony and order and attunement that we want, and we pay attention to the living details as all of that unfolds. And our relation from God: An Autobiography with God is very much like that In the Eastern form. And at one point, I'm sorry, at one point I asked about this Eastern way. Well, not having a personal God, don't they miss a lot? And God says everybody misses a lot because each revelation is partial, none is the whole, and I'm told that would be overwhelming for any given culture, be more than they could well use and maybe more than they need. So God works with the culture in that way what fits with that culture. And then the people work with the divine or however conceptualized, personally or impersonally, in whatever way succeeds in establishing their contact with the cosmic harmony.

Scott Langdon 42:31: Thank you for listening to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. Subscribe for free today wherever you listen to your podcasts and hear a new episode every week. You can hear the complete dramatic adaptation of God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin by beginning with episode one of our podcast and listening through its conclusion with Episode 44. You can read the original true story in the book from which this podcast is adapted, God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher, available now at amazon.com, and always at godanautobiography.com. Pick up your own copy today. If you have any questions about this or any other episode, please email us at questions@godanautobiography.com, and experience the world from God's perspective as it was told to a philosopher. This is Scott Langdon. I'll see you next time.