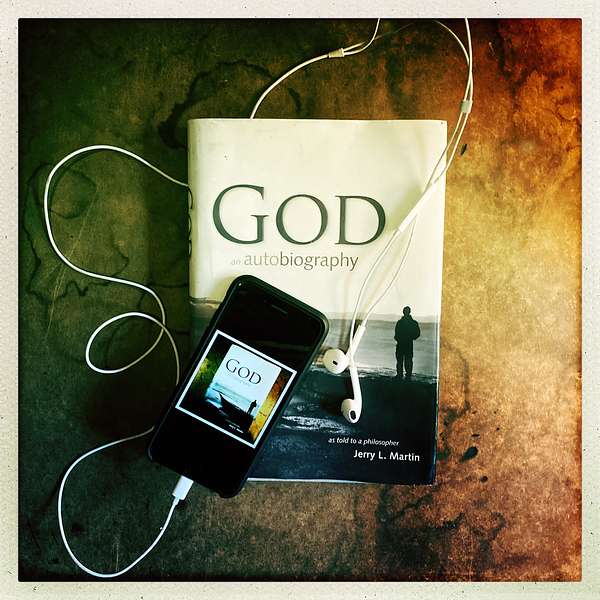

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

243. What's On Our Mind- Why God Allows Suffering: A Conversation About Pain, Purpose, and Presence

In this moving episode of What’s On Our Mind, Scott and Jerry revisit one of the most difficult questions in spiritual life: why does suffering exist?

Drawing from God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher, they reflect on God’s response to Jerry’s early questions about pain and meaning. God doesn’t minimize suffering—He calls it “the law of growth in the universe.”

Jerry and Scott explore how suffering shapes the soul, how grief expresses love, and how even ordinary moments—taking a photo, mailing a letter—can be spiritually rich. They also challenge the belief that suffering is a punishment or sign of guilt, offering instead a divine perspective that invites growth, presence, and compassion.

Whether you’re struggling or simply wondering, this episode speaks to the human need to find meaning in life’s hardest moments.

Related Episodes:

241. Jerry & Abigail: An Intimate Dialogue- What We Learn Through Love and Suffering

240. From God to Jerry to You- When Suffering Strikes: Finding Meaning, Love, and God in Hard Times

Other Series:

The podcast began with the Dramatic Adaptation of the book and now has several series:

The Life Wisdom Project – Spiritual insights on living a wiser, more meaningful life.

From God to Jerry to You – Divine messages and breakthroughs for seekers.

Two Philosophers Wrestle With God – A dialogue on God, truth, and reason.

Jerry & Abigail: An Intimate Dialogue – Love, faith, and divine presence in partnership.

What’s Your Spiritual Story – Real stories of people changed by encounters with God.

What’s On Our Mind – Reflections from Jerry and Scott on recent episodes.

What’s On Your Mind – Listener questions, divine answers, and open dialogue.

Stay Connected

- Share your thoughts or questions at questions@godandautobiography.com

- 📖 Get the book

Share Your Story | Site | Facebook | Instagram | Twitter | YouTube

Scott Langdon 00:17: This is God: An Autobiography, The Podcast, a dramatic adaptation and continuing discussion of the book God: An Autobiography as Told to a Philosopher by Jerry L Martin. He was a lifelong agnostic, but one day he had an occasion to pray. To his vast surprise, God answered in words. Being a philosopher, he had a lot of questions and God had a lot to tell him.

Scott Langdon 01:10: Hello and welcome to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. I'm Scott Langdon and this week, Jerry Martin and I share What's On Our Mind about suffering and God's answers to Jerry's questions about it. In every moment where there is life, there is suffering somewhere. Each one of us must contend with it. To Jerry and to many of us, the very idea of suffering itself seemed cruel and pointless, but God tells Jerry that's not so. In fact, God tells Jerry, suffering is the law of growth in the universe. What could that possibly mean and what could be the ramifications to our lives if we began to look differently at suffering? Here now are Jerry and me. I hope you enjoy the episode.

Scott Langdon 01:45: Welcome back everyone to another edition of What's On Our Mind. I'm Scott Langdon, I'm here with Jerry Martin and this week, Jerry, we're going to talk a little bit more about suffering. And unfortunately it's a topic that's always with us.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 02:23: It's a lot about where real life is, and spirituality of any kind with God in some other mode to be relevant has to be where we actually live, and a lot of where we live is in moments of suffering.

Scott Langdon 02:44: It seems like every religious tradition, even tradition that's not religious, take religion out of it. I mean it doesn't matter. Anyone you encounter who is having a human experience can point to what suffering is like in their lives. You know that they feel it in their own lives first person and they also experience the suffering of others. It's always been there and it's something that's always going to be, even though we try to do everything to kind of cover it up, push it away, wrestle with suffering. There's all this sort of talk about how to push it down, push it aside. What are we doing with it? God has some really interesting things to say about suffering and when you ask Him about it, He's really keen to talk to you about why, you know. At one point He says you know: don't fence with Me on the problem of pain.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 03:56: Right, right.

Scott Langdon 03:59: There's something, though, that is very significant about suffering. Yeah.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 04:04: And a lot of the worldviews try to deny it in some way or other. Because there's a kind of, in religions and many philosophies, there's a kind of cosmic optimism. Some people call it you want to think at a very ultimate level. Everything is just splendiferous, you know, like 4th of July fireworks or something, and it's then a pesky fact yeah, but I have a pebble in my shoe, this really hurts every time I step. And no, no, you don't.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 04:39: But of course God tells me somewhere suffering is just as bad as the people who turn against Me because of it say it is. So God, to me, doesn't at all deny that sharp reality of suffering. But there's still the challenge you don't have to deny it. But there's still the challenge of making sense of it. What's its role in the scheme of things in the universe, in the scheme of things in a person's life? And so you might ask even what is it for? You know, is it for anything or what? Some people like to talk about the absurd? Is it just kind of something that makes life absurd? Well, I don't think that's the right answer, but it's a good question. You know what does it mean?

Scott Langdon 05:36: God says to you that it makes life serious. Suffering is what makes life serious. If you go to where we host our podcast on Buzzsprout, that's a place that you can go and listen to all the episodes, or you can get it from Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, anywhere you get your podcasts. But I was going through some episodes in Buzzsprout and in the search bar I just typed in the word suffering. I was just kind of curious how often do we talk about suffering in this podcast? And so I typed in the word suffering and six episodes came up of the I guess this is 243 now that really in the title and in the words and however you categorize these things, suffering was sort of at the heart of the conversation.

Scott Langdon 06:30: The first time it's mentioned in our podcast in that kind of way is episode 13, which is in the dramatic adaptation of the book God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher. So episodes 1 through 44, as most people know, that's the dramatic adaptation of the book. In episode 13, you ask God about suffering. In fact, the title of the episode is I Ask God Hard Questions About Ego and Suffering, and I was looking through that episode and I wanted to read just a little bit of it and get what God is talking about when he's answering these questions about suffering. You start out by saying, by asking this very question, “Lord, does suffering have any purpose or meaning?” God says, “Of course, suffering is what makes life serious.”

The Voice of God 07:30: Imagine a world in which actions never resulted in suffering. Imagine a world without the pain of regret, without feeling bad about doing something wrong or shameful.

Jerry Martin 07:42: But disease serves no moral purpose.

The Voice of God 07:46: Now you're fencing with me on the problem of pain. Just listen. You will never learn from fencing. Disease, disaster, aging, death are essential aspects of suffering. We live in a physically vulnerable world of suffering. We live in a physically vulnerable world. That is the essential condition that makes life serious.

Jerry Martin 08:10: All that's rather abstract. What exactly does disease do for us?

The Voice of God 08:16: Suffering is the test of your humanity. There is no greater test than pain, how one copes with it. But that just seems perverse or cruel. No, that's not so. Think about your own times of physical suffering, in the hospital, for example. Those were full of growth.

Scott Langdon 08:50: So, God says a lot right there about suffering. He says, suffering is what makes life serious to begin with.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 09:01: Yeah, it does, and I guess the things I had started imagining... Suppose you lived without regret. Regret is a kind of suffering. You do something wrong, you regret it. And suppose you didn't regret it. You just happily skip along. Well, the whole blood would have been drained from the experience of doing something wrong and then regretting it, which is a crucial way you learn not to do something wrong next time. And suppose, when your child died, you felt nothing no pain, no suffering. The child may have died without suffering after all, so why do you need to add suffering? Well, you do suffer, because that's an expression of your love. In that case, that suffering means something. It's full of meaning, and it's meaning directed to the child and maybe the others who love the child, but there are others.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 10:08: And I start doing the fencing. Yeah, disease, you get typhoid fever, or there's an earthquake and the rocks fall down on people and just crush the whole village. That sometimes happens. Those don't seem—and God tells me well, don't do that kind of logic. Chopping, fencing, you know, yeah, but what about this? What about that? Can you explain this?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 10:32: No, just take it in, and then you would have to—rather than throwing these out as little counterexamples of meaningful—suffering can't be meaningful, because what about this? You know I stubbed my toe. Well, there's no meaning in that, you know. Well, this isn't counter examples of meaningful Suffering. Can't be meaningful because what about this? You know I stubbed my toe. Well, there's no meaning in that, you know well, this isn't going to get insight into the issue of suffering, and one of the things I think you really need to do is think about… think in real.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 11:01: These are made up examples, but think about the whole experience you went through and the context and what was going on in a time of suffering, and then see if you can go into it and what does it have to teach you? I guess that's what it is when you go into it. What meaning do you find there and what do you learn from it and how does it affect you? God says that suffering is the law of growth in the universe. Well, see if you can see, is there some way that I grew from this?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 11:40: Often at first you would think surely not. You know, it was just miserable, it was just setback, setback. But often, if you go into it with a kind of open mind, open heart, open sensibility and take in all the reverberations, not just the one you focus on at the beginning, which is the cutting edge of the suffering, I suppose, and how it affected you immediately, but go into the whole experience and in context and its unfolding, and just see, does this mean something in my life? Is it teaching something? Is it adding something where life would be less serious or less something else you know, less real, you might say, without the suffering.

Scott Langdon 12:31: When God says suffering is the law of growth in the universe, He also talks about the way we build muscle. And you think about weightlifting, you think about training your body to, you know, be in shape, and you're lifting muscles and you're tearing them apart and they're building back together stronger. That analogy makes some sense. When you look at it that way, you say, okay, what is this suffering breaking down that I'm rebuilding? You know that God is rebuilding in me. It's an interesting way to look at it.

Scott Langdon 13:09: At the same time, I feel like in my tradition, or the way I took in the tradition of my faith, growing up at the heart of it, in terms of who I would be, the character that I am, the human character. Innately, I'm not worth it. We're not worth it. None of us are, and so we need a savior. And this idea that just seems to get driven in again and again is if you're suffering, it's because you've done something wrong, it's because you haven't been as good a person as you could be. And it's not limited to just the Christian tradition. I hear talk of karma being that way, that if you do this, it'll come back to you. So this idea is not just exclusively Christian. It's not exclusively religious, even the idea that you know if there's suffering, then there's something that you're doing wrong.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 14:19: Yeah, or that everybody's doing wrong, or that's innate to your condition. The doctrine of original sin, you're guilty the day you're born, you know, because you inherit all of this sin of your species, you might say. And there are other secular contexts in which that, during a certain phase of aggressive feminism, I felt, God, being a man, I'm just guilty before I do anything, you know, because there is a kind of being a man was seen in a certain mode of feminism as so toxic that you just have to apologize, I'm sorry, I was born this way. I can't help it, you know. And so there are other secular forms of ah, people are no good or you're no good, some big category of people is no good and certainly come down to you.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 15:11: And of course a lot of our psychological problems have to do with precisely that self-condemnation. And it's often hard not to do that because we're all aware that you know, we're not as perfect as we like to be, we're not as excellent in this way or that way, we're not as successful, we're not as handsome, as healthy, as buoyant, as rich or whatever, as we might like to be as productive in whatever we're doing that's meaningful to us in life. So we can easily fall under that feeling of kind of worthlessness. And, of course, God has precisely the opposite attitude. In fact, He says that you'll love, either God or Jesus says, you'll love us better. Love God better. If you love yourself.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 16:07: Ideally, you should love yourself the way God loves you, which is really unconditional. You know, like the ideal parent. You know unconditional. Or the way what makes dogs so wonderful. They seem to love you that way. Well, that's how you should feel about yourself, and it's not a self-inflation, it's simply a self-appreciation. And therefore you want to take care of yourself. You want to keep yourself healthy, you want to keep yourself moral. You don't want to do bad things and make yourself crummy. You think of Portrait of Dorian Gray. You don't want that ugly painting up in the attic. No, you want to keep your soul as beautiful as you can, and that's part of the cosmetics of life, is the inner cosmetic. But you're right, Scott, that's a challenge that we feel and that can't be right.

Scott Langdon 17:43: These recent episodes that have just passed episode 240. From God to Jerry to You. 241. Jerry & Abigail: An Intimate Dialogue, your third conversation with Abigail. And episode 242, our spiritual story this time is from Rosemarie Proctor, and I want to look for just a second at episode 242, Rosemarie Proctor. She was somebody that you interviewed and she came to God An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher, your book by chance, she says, as most things do in her life she mentioned, and at the time of having it recommended to her to read, her spirit was very open and she was at a place of being able to accept what was in front of her. She herself says she's 85 years old. She's very comfortable in where she is in her spiritual life now, but it hadn't always been that way and, like many of us, had a pretty long and complicated spiritual story.

Scott Langdon 18:44: She was raised Catholic and then nothing for quite some time, just it didn't work and couldn't find anything. And she was married to her husband and then about 22 years, 22 years ago, he suddenly died, and when he did, he had been going to this Episcopalian church and was, you know, quite faithful there and the minister came and offered a prayer in constant, you know, to console the family. And in the middle of that prayer Rosemarie had this experience where she was resisting, at first, just the idea of the prayer, but in the midst of it she felt this knowing that everything was going to be okay. And that was the moment for her that really changed everything and just sort of maybe it was like a weight that came off of her. I don't know, I have a similar idea of what that feeling might be, but I was very fascinated by her story and that episode. It was a really lovely interview.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 19:52: Yeah, I'm curious myself, Scott. You say you have a feeling, I have some vague sense, but I don't think I've had precisely that experience, though I've heard others for whom it was very important to come to some point where they get the sense that in some fundamental way, everything is going to be okay. But I would be interested, when you related so strongly to that, how you would explain that. What is that feeling? In what sense is everything going to be okay?

Scott Langdon 20:28: I'm sure that there's an experience for some folks where there's a definitive moment like that. Rosemarie speaks of that one and in the context of this conversation that might be the one and only sort of pivotal time she felt like that. Upon more questioning and maybe further conversation, she might express she's had that feeling a few times. I don't know. I know for me I've had it enough times to recognize it as that feeling. So when she described it I kind of felt like, yeah, I know what that's like, and here's an example of one of the times that I felt it during the pandemic, when everything was shut down.

Scott Langdon 21:18: I live here in Bristol Borough in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. It's a nice little river town. It's very quiet and at night the lights in the town are just the street lights and the lights that come off out of the houses are just colorful in a way that's just different to me. I don't know. I just sensed this idea and I love to take photographs and so sometimes at night my dog and I would go out after dark and just sort of walk around Bristol Borough and I would take photographs of things that were interesting to me Houses, the way the light would shine on a car, or something like that, and I just remember one specific time and then it would happen different ways like this, but one time I put my camera up to my eye and was looking at a shot that I had an idea in my mind what it would look like framed. And when I put the camera up and I, it did look like that in the frame and I felt when I pushed the shutter, there was no action going on. It was just maybe a shot of the house and the way, the light and the sky. And when I pushed the shutter button, it was this notion that this moment is just what it's supposed to be, just so, even more like I created this frame, this vision, just for you to see, because even if somebody else came and stood exactly where I did and put their camera up exactly the way I did, it would still be a different photograph. That moment that I took that picture was the only moment that was ever going to be and it was just me and whatever it was that said push the shutter, now. I believe that to be God. So in that moment what I was being taught was everything is perfect right now. As it is, it's okay, and I think it's a notion to always recognize the present moment, that it is what it is. That's a phrase I used to hate so much. My friend would say it and I was like it is what it is, but there is just something about resting in that everything's going to be okay. Now, as Abigail says, God can't mail a letter. So there are letters to mail, right, there's letters to mail, and yet, at the same time that you're on that trip to mail that letter, whatever it is, everything is just right, everything is okay.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 24:19: Yeah, that means in part you have to carry that same spiritual sense we might call it, but same feel that you had taking that photo, that this moment is exactly right and this picture is exactly right in this moment. And you need to carry that over. We need to carry that to other things, like mailing a letter. You know, why shouldn't mailing a letter be? Ah good, this is what needed to be done. I've opened the thing, we've got one in front of our house and you open it and stick it in the letter and close it and you walk back to your front door, and why shouldn't that be a kind of perfect moment? Who knows what perfect means in such a context? And this is why that expression you don't like is it's the right moment for just then. You know, that's all. It's not perfect in the sense of fireworks going off or something, or ecstasy, but it's, you've just now done just what you needed to do and it's done. And in some way, God is a partner in all of these things.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 25:43: But there's something you know we do so much in life without paying attention you run and drop a letter in and then, because you're on the way to do something else, but there's something awfully good. Well, they say, stop and smell the roses. Well, it's not always roses, but pay attention to what you're doing. Take in each moment of what you're doing. You can't take it into the point of distraction or just slowing you down, as though you're going to stop in front of the mailbox even though you've got another errand to run. But you can nevertheless have some feel of the moments of your life, as if, well, these are kind of precious, aren't they? And you're in relation to something. Your own presence is something of value, your own presence to the situation. What you're doing is right, and you're also in the presence of something more than just you and the letter and the mailbox.

Scott Langdon 26:44: And when we listen and pay attention to what's around us, and I can say this for myself, when I'm in those moments of depression and despair and suffering about things and I tend to isolate, you know, I tend to not want to be around other people, not want to go outside, not want to walk, not want to engage, even at the local convenience store at a Wawa you know, but there's something inside me that is asking me to encounter others. When I'm feeling that way, to look around, it's almost like I'm being called to see what God's response is for me. God, where are you? Okay, well, well, you're not going to find Me in your basement. You have to get outside and look around.

Scott Langdon 27:41: So go out to the wawa or something and get a little something and put it on the counter. And behind the counter is Marianne and you can tell because her name's on the tag, and she gives you this smile and you smile back and she says something like that's a beautiful smile and and you're like okay, and then you get back in your car and you come home and you're like that was an encounter that had meaning. We noticed each other. It came up for air for a few minutes. You know, like, how are you in there? Um, you know, and it means something. But I find that when I isolate like that, that God is calling me to like I'm sending you folks, I'm sending you people, it's palpable sometimes.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 28:44: And sometimes our moments of suffering do lead us to isolate because we don't feel up to doing anything more than just oh, I have this tendency. We have a lot of suffering. Just recently, Abigail has a more dramatic suffering. I've got some other ailments that have cropped up, and in those moments of pain and discomfort I'm not wanting to relate to anybody or anything. You know, oh me, poor me, is the only thing on my mind. Oh me, that's my version of oh. Why do bad things happen to good people? It's just oh me, poor me. You know, the thought begins and ends right there.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 29:23: For me, that thought begins and ends right there, but in fact I've often been surprised by this if someone is nice to me at that moment, oh, that's nice. I mean, you think it can't do anything for my particular physical pain, but it does, because we're whole people. After all, we're not just ghosts and machines, as one philosopher put it at one point. You know, with the body we're steering around like a car. No, we're one organic being, and part of that is we're beings who live in the company of other people. That's how I know I'm a person. Is that other people are persons and act to me as a person and you know we're all in this interaction with each other. So these moments of recognized suffering give us that opportunity to almost realize our personhood and our interpersonhood.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin 30:19: And I commented Abigail feels during her terrible time. I was her helper 24-7, and, upstairs, downstairs, helping her shower. She couldn't do anything on her own at the beginning. And I was there and she thinks, oh, poor Jerry, and as I think I say in my podcast, it was a blessing. You know, you want love not to be an inert feeling. Okay, it's palpitating my heart. I love Abigail, but you want it to be enacted. Love should be an action verb. I love her- meaning, I'm doing something, and so this gave me an opportunity to enact my love and I never regretted a single moment of it, as far as I can recall, even though it went on for weeks into months. That's fine, that's how you live out your love, and okay. So those are, in those particular cases, some of the meaning of suffering, some of the benefits of suffering, some of the lessons of suffering. Thank you for listening to God and Autobiography the podcast.

Scott Langdon 31:53: Thank you for listening to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. Subscribe for free today wherever you listen to your podcasts and hear a new episode every week. You can hear the complete dramatic adaptation of God: An Autobiography, As Told To A Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin by beginning with episode one of our podcast and listening through its conclusion with Episode 44. You can read the original true story in the book from which this podcast is adapted, God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher, available now at amazon.com, and always at godanautobiography.com. Pick up your own copy today. If you have any questions about this or any other episode, please email us at questions@godanautobiography.com, and experience the world from God's perspective as it was told to a philosopher. This is Scott Langdon. I'll see you next time.