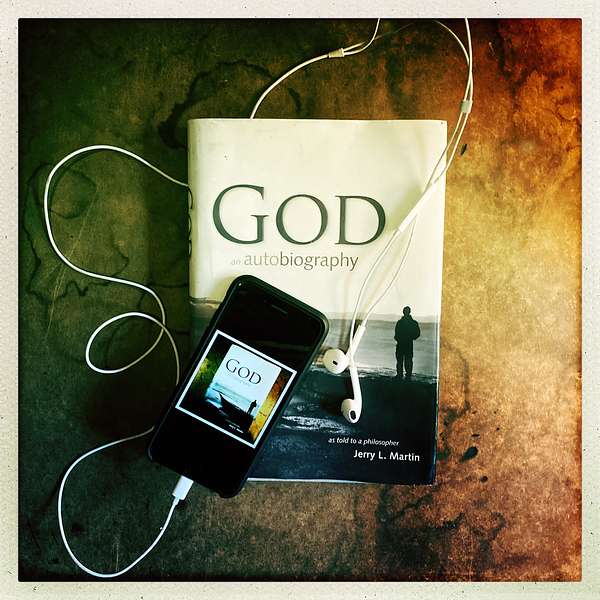

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

GOD: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher - The Podcast

262. What's On Our Mind- Truth-Seeking Beyond Reductionism: Experience, Meaning, and a Developing God

In this episode of What’s On Our Mind, Scott Langdon and Jerry L. Martin explore truth-seeking beyond reductionism. Drawing on Radically Personal, lived experience, acting, spiritual stories, and prayer, they ask how we know what’s real—and why meaning cannot be reduced to just chemistry.

The conversation ranges from new atheism and scientific exclusivism to Stoicism, human fulfillment, empathy, and a developing God who suffers with us. An invitation and reflective dialogue on experience, purpose, and spiritual openness for truth across life.

Related Episodes:

261. What’s Your Spiritual Story: Amanda on Love, Trauma, and Discovering a God Who Suffers With Us

260. Radically Personal: A New Philosophy of God — Life Seeking Understanding

255. What’s Your Spiritual Story: Laura Buck on Becoming Visible, Intuition, Loss & the Inner Voice

Other Series:

The podcast began with the Dramatic Adaptation of the book and now has several series:

The Life Wisdom Project – Spiritual insights on living a wiser, more meaningful life.

From God to Jerry to You – Divine messages and breakthroughs for seekers.

Two Philosophers Wrestle With God – A dialogue on God, truth, and reason.

Jerry & Abigail: An Intimate Dialogue – Love, faith, and divine presence in partnership.

What’s Your Spiritual Story – Real stories of people changed by encounters with God.

What’s On Our Mind – Reflections from Jerry and Scott on recent episodes.

What’s On Your Mind – Listener questions, divine answers, and open dialogue.

Stay Connected

- Share: questions@godandautobiography.com

- Get the books: God: An Autobiography, Radically Personal

Share Your Story | Site | Facebook | Instagram | Twitter | YouTube

Scott Langdon [ 00:00:17,220 ]This is God: An Autobiography, The Podcast — a dramatic adaptation and continuing discussion of the book God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin. He was a lifelong agnostic, but one day he had an occasion to pray. To his vast surprise, God answered — in words. Being a philosopher, he had a lot of questions, and God had a lot to tell him.

Scott Langdon [ 00:00:58,940 ] Episode 262: Welcome to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. I'm your host, Scott Langdon. And on this week's episode, Jerry joins me once again and we share What's On Our Mind. We talk about an aspect of Radically Personal that really intrigued me, and about how Amanda Horton's spiritual journey in our last episode affected how we look at our own spiritual journey. We also talk about experience and how important it is to take experiences in. I compare this to what it's like playing a character in imaginary circumstances, and what it must be like for God to deeply know each one of us. Here's What's On Our Mind. I hope you enjoy the episode.

Scott Langdon [ 00:02:03,130 ] Welcome back, everybody, to another edition of What's On Our Mind. I'm Scott Langdon. I'm with Jerry Martin. And Jerry, I'm really excited about the things we're going to talk about today.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:02:12,330 ] Well, we've certainly had some recent episodes that I thought were very interesting — deep — and they’ve stirred further thinking. So we're going to do some further thinking, maybe.

Scott Langdon [ 00:02:25,050 ] Yeah, and that's why I really cherish these What's On Our Minds, because as I'm working with these episodes, things come up — ideas — like, “Oh, I like this,” or “This is confusing,” or “This makes sense,” or I’m coming up against something in my daily life. We were talking about this unit, which I like to focus around the Radically Personal episode of the unit. And in this unit — it was Episode 260, your second episode of Radically Personal — a line stuck out to me.

Scott Langdon [ 00:03:03,380 ] And I want to quote it right now. You suggest, quote: “An open, non-exclusivist epistemic strategy in religion and other fields has a truth-seeking advantage.” And a couple of things about it. First, the first part — “an open, non-exclusivist epistemic strategy” — I want to talk about that for a second, in religion and other fields. And the reason you suggest it is it has a truth-seeking advantage. Can you talk a little bit about those things?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:03:37,530 ] You know, what are we trying to do as we think about things, as we experience things, as we examine them? Turn them over in our minds, maybe turn them around in our hands — you know — look at them, talk to other people. What's their experience? How do they think about it? Well, if you're open, you're going to take in a lot of evidence. And what is experience? It's evidence. It's evidence of the reality around us. And you want to take in as much of that as you can.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:04:04,460 ] And not leave anything out — just because you're clinging to a certain worldview, which can be, “Oh my — religion just says A, B, and C, and so I only believe A, B, and C.” And if something else looks true — or is an arresting experience, something worth investigating, figuring out, “What is this?” — you say, “No, no, I can't look at it because I believe in A, B, and C.” And it's not just religion. People often talk about religion as if it's the only dogmatism around, but all of our little worldviews are like that — including scientific worldviews. We carry little belief systems in our head. Our politics is like that. We carry belief systems in our head, and we just resist any counter-evidence.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:04:49,120 ] Basically, it's what scientists call confirmation bias. You start with your own beliefs and you only accept evidence that confirms them, rather than taking it all in and maybe revising beliefs — being open to change of beliefs. And if you're interested in truth, you have to be open to changing your belief when new evidence comes in.

Scott Langdon [ 00:05:12,390 ] I think about that in my craft as an actor. And I think about different actors who come to a job with a different process. You know, each one has their own way of preparing a role. Maybe they do some more work beforehand — watching other people's performances or reading source material — or only sticking with what's on the script page. They don't do as much backstory on their character, whatever it might be.

Scott Langdon [ 00:05:41,740 ] Over the past few years, I've been getting a little bit more specific about what I specifically do, because I'm interested in: How do I prepare? How do I get ready — not just for the role, but during rehearsal? How do I shape a character? And then once the show is open, how do I keep it fresh every night? Those kinds of things. What is my process? And so it's been interesting to kind of work on that.

Scott Langdon [ 00:06:10,300 ] But it applies here in this context, because the idea is to come to the job and put the whole show together — and for me to do my part. So whatever I have to do to bring the fullest version of my character to the show. And the show — you know — the director has the director's vision for what it will be and how that character fits in. So if I can align myself with the director's vision and do the best I can, and then allow for everyone else to have their process — whatever it's going to be —in service of the same thing, which is the vision of the show, and the director, and the piece, right? So if somebody is really, “I'm Stanislavski method — that's what I do,” or “Oh no, I'm more Chekhov,” or, you know, some of the great acting teachers — whatever it might be — it's not a question of “My school is better than your school.” It's: In the end, can you get to the job and deliver your piece of the overall puzzle?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:07:18,140 ] In whatever way works best for you. I mean, part of the point of the book, Radically Personal — which is the book I wrote, though it draws, of course, it’s inspired by God: An Autobiography, you might say — but I'm also trying to think through these things. I'm an epistemologist, which means a theorist of knowledge. How do we know what we think we know, and how do we know it? You know, what's the range?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:07:45,000 ] But the point of Radically Personal is this: it's up to each person. You can, if you want, just sign up with some religion and say, “Well, I'm going to believe whatever they say.” You can sign up with the Communist Party — a lot of people did that, especially in the mid-20th century — believe whatever the Kremlin says. That'll be my line. Or you can — any other myriad things you can sign up for — and, as I put it, try to outsource your beliefs.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:08:23,000 ] But ultimately, you're responsible for the outsourcing too. Why did you choose this church, or the Communist Party, or whatever other thing you chose? The buck stops here with the individual. You are in charge of your own beliefs, and you are responsible, therefore, for the worldview that you are coming up with.

Scott Langdon [ 00:08:40,049 ] In today's society, we talk a lot about science and how to know the world. So an epistemic strategy of science — or materialism — where we would know the way we know things is, in a sense, an exclusive way to know things, which is scientifically. So in one way, when I hear somebody like a new atheist — this new atheist movement — so that might include Dawkins, Christopher Hitchens, Sam Harris (I'm thinking in particular) — who would say something like, “Religion is going to eventually be replaced by science.”

Scott Langdon [ 00:09:16,000 ] Because — and I think I heard him talk one time about an example — it might be, say, in Jesus' time, a little girl has a seizure, and they assume and go to religion for an explanation for this. Well, it's demon possession, and so they would treat it in that way. Well, nowadays — same seizure, same things happening physically — we now understand that there's something in the brain. It's epilepsy. We can take medicine, we can have surgery, or whatever the case might be. And so it's a fact of the equipment.

Scott Langdon [ 00:09:46,990 ] And they would talk about meditation — not in terms of its spiritual benefits and connection with God or another — but just that the physicality of your body is better when you meditate. So they would just kind of look at it as: only things we can, quote-unquote, know. But that seems to almost be a religion of its own — an exclusivism of its own.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:10:29,230 ] Yes. There are people — I'm often struck by those old movies I always loved, Friday Night Frights — they used to have these movies. There would always be something kind of scary or interesting. One typical plot would be: there's a ghost in the building, and there would always be one character who represents science. And that character — usually a science major at State University — they would say, “Anyway, we're scientists. We don't believe in ghosts.” That's the wrong thing to say.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:11:02,000 ] That person — if he or she is really a scientist — should be saying, “I'm a scientist. Let's investigate.” You shouldn't have, prior to full investigation, an a priori view about what's real and what's not real. And yet, those people — a lot of real scientists don't make this mistake — but people who are sort of science groupies do make that mistake. They just think: whatever their idea of what science says — they just think that's the last, final, and only word. Let me make one comment about that specific sort of argument, okay.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:11:44,160 ] You hear a divine voice — something's going on in your body. This is how our bodies work. This is how life works. You are an embodied vehicle through the world, and so everything is processed through your body. So you meditate, and of course the chemicals in your body are different.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:12:03,000 ] One problem with that argument is that it's an argument to dismissal. “Well, this isn't evidential because it's just chemistry in your body.” So is mathematics!

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:12:13,410 ] Mathematics. Something happens in certain parts of your brain. You could say, “Oh — E equals MC squared — that's just this part of the brain lighting up. That has no validity.” Our moral judgments. You can easily dismiss those: “Oh well, those are body chemistry seeking ideal social approval,” or something like that. You know, it's easy to come up with these reductionist theories, but you throw out — in the end, I guess my point is — you throw out science itself.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:12:45,000 ] What is the experience? You're looking at laboratory dials — and something's going on in your body that makes you think, “Oh, this tells us that,” you know, whatever it tells us about quarks or something. Well, that's some theory somebody's come up with, and something is going through that person's brain. Some chemicals were being activated. This proves nothing. That your body is going through a process when you experience or think proves nothing.

Scott Langdon [ 00:13:12,140 ] Well, I used to think about — well, I still think about that. The occasion was when I was running, preparing for a marathon — my first marathon — ten years ago now. Well, a little more than ten years ago now. I was about at mile seven when I experienced runner's high. And I remember it very distinctly because, you know, I'd read about it or whatever.

Scott Langdon [ 00:13:42,000 ] But it was in the spring, and I had in my earphones — I think — the soundtrack to Pride and Prejudice, and I was going past these beautiful bushes and this nature along this path that I was on. And I was thinking: it feels like I'm in a carriage in, you know, 18th century — late 18th century — England. And I felt myself just gliding like I was in a carriage. And I felt blissful and wonderful about it.

Scott Langdon [ 00:14:12,000 ] And then I realized: your legs are moving. You're actually running. I had forgotten, you know? And I was like, “Oh.” And that's what they call runner's high. Now, it is explained that, you know, this part of your brain is doing this and your oxygen levels were blah, blah, blah. I am fascinated by that conversation about what's happening with my equipment — you know, with the body. That's very fascinating. Thank you for explaining.

Scott Langdon [ 00:14:42,070 ] And my question still is: why that experience then? That particular experience — is blissful, is joyful, is peace. I know what it feels like to not be stressed. And more than that, we can understand one another when we say something like that. “Jerry, do you know what it feels like to not be stressed?” And you could say, “Ah, yeah, I do.” It kind of feels like this, and I could go, “Oh yeah, I do too.”

Scott Langdon [ 00:15:10,000 ] So there's some kind of connection between the individuality of us — the particularity of us — that can't be explained by what's going on in the brain, I don't think. It leaves too much out there.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:15:23,990 ] Yeah. Nobody knows more — is more finely attuned — to what's going on in their bodies than the great Eastern meditators, you know, the Hindu and Buddhist meditators. And there are interesting interspiritual discussions when those people get together. It's very fruitful because they're comparing notes on things like breathing — you know, breathing — and relaxing the different parts of the body, and focusing in ways that you eliminate distractions. And a lot of that is just physical. And they know that.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:16:03,000 ] And you're making — you know — you sometimes have to slow down your heart rate. They know how to do that, you know, supposedly. I don't doubt those reports. By meditating, you can slow down the rate of the heartbeat. And this can be good for you. And anyway, whether it's good for you or not isn't the point. It's that we have these high experiences — the highest experiences we can imagine — high moral insights, high religious epiphanies. And in each of these, something's happening in the body, of course, because we're embodied.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:16:46,070 ] But that's not all that's happening. I mean, the problem — my undergraduate teacher, wonderful guy, philosopher Philip Wheelwright, he's quoted a couple of times in Radically Personal — but one of his main mottoes, as you might say, was: never say “nothing but.” Never close it all down.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:17:12,000 ] Because almost nothing — you might say — almost nothing is “nothing but.” You know, everything has resonances at multiple levels. And you think about sex. What could be more physiological than sex? And you can take all of our love lives and the civilizational image of the romance novels — you mentioned Pride and Prejudice — you can reduce it all to some physiological function. Thereby, what would you achieve? You erase its meaning.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:17:48,000 ] So Pride and Prejudice becomes a meaningless book if you do that reductionist thing. But we all know — we read it, we recognize some element of ourselves in it, an element of our own hopes and dreams and fears and so forth in that book. And I don't know how Sam Harris reads literature or one of these other new atheists, but I wouldn't trust their interpretation. I wouldn't trust them to actually understand what it's all about because they're so insistent: “I believe A, B, and C. I believe A, B, and C. I believe A, B, and C — period.”

Scott Langdon [ 00:19:00,290 ] We've had a couple of really great What's Your Spiritual Story episodes — the last few. We had our own Laura Buck on two times ago, and then just last week, Amanda H — Mandi. Our own Amanda. And it was a wonderful episode. I really enjoyed the conversation that the two of you had. And there's so much to be said about it. And we might be able to come back to it another time — even maybe with Mandi at some point.

Scott Langdon [ 00:19:33,600 ] But I wanted to talk about a couple of things that popped into my awareness as I was listening to the episode and working with it. And one of the things is that early on in her story, one of the words that popped out for me — that she used a few different times — was that she didn't feel safe.

Scott Langdon [ 00:19:56,290 ] Safety was a big thing. So in her family — and so being able to explore God, to think about the idea that inside of her there might be something pulling her toward a divine being or a divine calling — there was not a place where she was physically, whatever age she might have been, that she felt safe.

Scott Langdon [ 00:20:23,070 ] And then, when she did feel safe — get to a place where she felt safe — a lot of that had to do with some of the places that she found early things that made sense. So some of the philosophy that she went to, and then was able to go to a yoga class and a meditation-type of situation and experience something there — felt safe there — felt this energy. Safety is an interesting word.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:20:51,900 ] Yeah. Something that has struck me as we hear these spiritual stories — which I just think are precious, to share these and to listen to them — because we all live these, you know, we say private spiritual lives. And even in a congregation or whatever, your own journey is your own.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:21:18,000 ] And something I've noticed: people start off in life at very different places. Each life has certain challenges. I'm told that in God: An Autobiography, each life has certain challenges. And almost the first job in your life is a kind of diagnostic: you know, what is my situation?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:21:42,000 ] And one of the challenges is you've got to be truthful about it. If your mother is an alcoholic, for example — that's not Amanda's situation, or anybody I think we've interviewed — that's one possible life situation. Mom is an alcoholic. You've got to cope with that. First, it means you've got to recognize it rather than sweeping around it.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:21:58,000 ] And then you've got to figure out: okay, what is my life strategy in light of this fact? And it might be — maybe the father is better, and you seek protection from the father: safety, guidance, and so forth from the father.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:22:20,000 ] Maybe — I do have a friend I knew years ago who was in a terrible home situation, and she got married early. It was just a way to get out of the household. And that, as far as I could tell, was probably the best move she could make. You know, there was no alternative.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:22:32,999 ] And when Richard Oxenberg did an interview on his spiritual story — and I always remember this since the first time I met him — he told me: whenever I talk to him, it's in my mind that, as a child of — I don't know — seven or eight or something, where he was close to his sister and they would play together, they were in the front yard, maybe he was even younger. She runs out in the street, gets wham — hit by a car — dies before his very eyes.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:23:06,000 ] And I remember talking to Richard. He always talked about needing, trying to find peace. Well, and I think we call that episode — because he did find peace — and it's called “The Peace of the Path of Understanding.” You know, it's what he found.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:23:24,530 ] Well, Amanda grew up in a situation that we hear about — and we might have heard more. I felt I failed to explore much. It turned out her father wasn't her real father. And we never hear a story about that real father, but the father in the home that she thought was her real father was also a kind of abusive, rough character. Fortunately, her mother and sisters she just cherishes because they provided some safety — but the home was not safe because of this out-of-control stepfather.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:24:16,000 ] And then one is on a search, and she made a very intelligent move, in terms of worldviews, to start reading the Stoics — the ancient Stoics. And you don't have to believe quite as much as you do when you accept theologies of this or that variety of religion, but they just taught you — it’s in the serenity prayer that alcoholics use — that's basically drawn from the Stoic wisdom: figure out what you have control over, and try to maximize that, do the best you can.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:24:40,340 ] And with AA, it's what in yourself you have control over and what you don't. And you kind of don't worry so much, the Stoics said, about what you can't control. A lot of life — the events of the world — sweep over you. So don't get agitated about that. It's beyond your control.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:25:05,180 ] If there's something you can do — that you can improve your life — you need to get a better job or something, then go get a better job. But if you have just some inbuilt disability, for example, well, you may just have to live with that rather than thinking, “Oh, oh — you know — I'm stuck with it.” But anyway, Amanda saw this challenge, and the challenge was feeling safe. And I suspect she's not the only person for whom safety is a big challenge.

Scott Langdon [ 00:25:33,600 ] Yeah. Safety is vulnerability, but it's also a vulnerability in many ways — emotionally, but even physically in some ways. And up against a wall — it's really interesting, her story, because she's up against every patriarchal influence. It's negative, but also says this is the exclusive way to do things: this — this is the way you do it, and this is not good over here, right?

Scott Langdon [ 00:26:03,000 ] But she reads the Stoics — very patriarchal kind of an influence in some ways, you could argue — but finds this greater truth in there, this thing, this inner truth-seeking advantage.

Scott Langdon [ 00:26:25,640 ] When you talk about — so she's found herself to be able to be more open and non-exclusivist. So she's looking at the Stoics. She's also looking at Chinese influence with a yoga teacher and friends in that way, and finding the Tao Te Ching and reading that and just being very curious. So she's developed what you've talked about: this open, non-exclusivist epistemic strategy.

Scott Langdon [ 00:26:57,240 ] Not necessarily in religion at first, but you say in religion and other fields — because it has this truth-seeking advantage. And that's what she would argue, I think — and I would certainly argue from listening to her episode — was her primary desire: what is true here?

Scott Langdon [ 00:27:22,000 ] And I think when folks who find themselves in a place where they don't know what their spiritual story is — or where it would lead — or where they haven't maybe even thought about it — but if you zero in on: do I seek truth? Is that important to me? Then I would say, “Take a look in those areas,” because I feel like that is your spiritual story: when am I seeking truth?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:27:47,140 ] Yeah, that's — I mean, the key of human life is: you live in reality. You know, you're not a self-sufficient bubble, you know, regulating everything yourself, determining everything. Some people live as if that were the case. You try to live within a bubble of illusion, you might say, and maybe use their real-world capacities to buttress that illusion. But we, in fact, live in reality.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:28:18,060 ] And you want to live in reality as it is. So it behooves you to take in whatever evidence you have — experiences you have — that you hear others have, or read about, that others have. Take it in, because you want to live — actually — in relation to the real reality as it is.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:28:39,470 ] There's another factor here, I think. I think we want to live with regard to the highest reality. Now, it seems that some people resist that. They resist it. The reductionists resist it. A higher reality maybe seems to Sam Harrises of the world — and I don't want to be commenting about an individual whom I don't know; just take him as a type rather than a comment on an actual person — but that type of person may find it unsafe to go beyond the physiology, the body chemistry, that level of understanding.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:29:38,000 ] But on the whole, I think we're sort of teleological creatures. We're purpose-seeking creatures. And that's not an illusion — as I suppose maybe new atheists would think it is — just some desperate human need. But no — it's: the acorn grows into an oak, the flowers turn to the sun. You know, the human beings seek their fulfillment. You want to be — the nature of a thing is basically to be its fullest version, not its bare minimum version.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:30:04,240 ] We certainly, human beings, with all of our wonderful capacities — we can write poetry, we can do mathematical physics, contemplate the whole galaxy, and we can be funny. I've been reading the autobiography of Woody Allen. It's very interesting. And you see Woody Allen's life — and he was thought to be an intellectual, but he says, “No, I'm not. I was just trying to be funny.” His whole life was trying to be funny. And he was good at it. He was making good money writing for comedy when he was a teenager — making more than both his parents combined — in just a few hours a week because he could write 50 jokes that were usable by Jack Benny, you know, in an hour or two.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:31:09,910 ] And so he's about that. But we have all these capacities. That's just one. You're an actor — that's another capacity. And any individual isn't going to be a thousand clowns, to use the title of a movie.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:31:34,000 ] But you've got to figure out: what are your potentials? You might say, almost like: what is the ideal Scott Langdon? And by “ideal,” I don't mean something unworldly, but just take the real Scott Langdon. And if you can fulfill yourself — and there are always options to that, of course, internal and external.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:31:58,000 ] Can I be the ideal Jerry Martin? I've got a job to do here. Can I do it adequately? And you want to do it better, and you want to do maybe more — because sometimes there's something you could get around to doing that you just haven't.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:32:17,920 ] Okay, well, then if that comes to you — you really should be doing the second thing. If it should be going out square dancing or something, then try to work that in. But you want to be your highest, and the highest, of course, from my point of view, as I understand reality, the highest is divine.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:32:40,000 ] And the divine has different faces and different aspects — can be conceptualized in different ways, can be actualized, experienced. Here I'm thinking of the different methods of meditation, different types of worship, different types of religious community, different kinds of music, dance. All of these things are part of actualizing, relating to the spiritual level of reality. And if you're not doing that, you're kind of hunkering down under a low cloud ceiling.

Scott Langdon [ 00:32:44,920 ] I think when we do those things the best, what that means — what that entails — is a concentration, a tuning in. You talk about being tuned in. We talk about being sort of one with God. What does that mean? I feel like it is every moment. We are creative beings. I feel like that is a way that we are in touch with God — a process of constantly creating.

Scott Langdon [ 00:33:15,000 ] And when you are creating, you are focused on that thing — not the future or the past — but you're focusing on working on that creative thing. Where you are focusing your attention becomes very key.

Scott Langdon [ 00:33:37,520 ] Am I focusing my attention on love and goodwill? And if I'm being open to how to be in touch with God-like things — if that's where my attention is focused — and we talk about, you know, what are things I have control of? What don't I have control of?

Scott Langdon [ 00:34:03,020 ] If I had a car accident or something — or a slip and a fall — and I hurt this part of my brain, and then I don't remember my wife, or I don't remember — or I start cussing all of the time, which is not like me. Or, you know, we have stories and experiences of that kind of thing happening. That might lead a new atheist to say, “Well, see — I mean, you can't control your morals because now here you are cursing,” or doing whatever. “You can't really focus your attention the way maybe you used to.”

Scott Langdon [ 00:34:26,420 ] But there is something about locking in, while I'm aware of being aware of that creative process. Whenever I play a character, I feel like if I'm not concentrating on what I'm doing — listening to other people, making sure I'm in my light or whatever — if I'm thinking about what's for lunch, there's that little part of me that is not my character. So I'm not allowing my character to be fully there.

Scott Langdon [ 00:34:59,210 ] And if I take a step back and I imagine that God is like that with me — that God would be concentrating on me all of the time — that's because that's what God is. So if I'm thinking, “How can I be like God?” I might think, “Can you be present and concentrating on God-like things all the time?” Is that something we could do?

Scott Langdon [ 00:35:21,080 ] And so that becomes an objective. And in that becomes this idea of safety. But it also is something else. You start to form this other thing that Mandi talked about, which is trust.

Scott Langdon [ 00:35:36,590 ] Because Mandi talked about the idea that not feeling safe — also there was no trust in her patriarchal figures. But yet, when she started to read your book and started to be involved with our project, started to meet a God who was not perfect — so if you do these things, you get praise and reward, and if you don't do these things, you get shame and punishment — but instead, a God that was developing, learning — that kind of God actually is, in Mandi's estimation — and in mine as well — real. That's a God that I can work with. That's a God that can work with me.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:36:14,690 ] Yeah. I wrote a piece early on based on — you know, I was told this. One of the first things I was told in praying was: “I'm an evolving God — the developing God. And I found that so puzzling. It violated, you know, my whole idea of God.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:36:37,000 ] And then I prayed about these great perfections — God: omnipotent, omniscient — and I just found that totally puzzling. And I know some people, when they're either talking to me about it — I was going to say that I wrote this piece called “An Inconvenient God,” you know — if you could order a God online, you would order a perfect God.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:37:05,170 ] And that would be a convenient God. In fact, you'd order a God who makes everything just right — the way we imagine a good mommy, you know — heals every little scratch that the child gets and, you know, kisses it and makes it well. Well, we'd have a God that's kind of like that. God says at one point, “I'm not a rescue helicopter.”

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:37:29,920 ] But we kind of like a rescue helicopter, wouldn't we? But no. And the problem with those people who have a perfect-being concept of God: in God: An Autobiography, God completely says that concept doesn't even make sense. Rejects it totally.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:37:58,000 ] But for those who have a perfect-being concept of God, they have a big problem explaining the world around them, because it does not look like a perfect world. And so if God somehow has some big role here as creator, sustainer, designer, or something else, it doesn't seem to match the product, you might say.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:38:24,000 ] It's all more complicated than that because there are aspects of perfection, you might say, in reality around us. In fact, I'm going to be doing a From God To Jerry To You about this kind of difficult-to-understand topic. But I did find it interesting that you and Amanda both found that to be a more trustworthy God.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:38:38,000 ] Because I know other friends — other readers — have said, “Well,” one said, “that's not a God you could worship.” Well, I didn't think of the main role of God in my life as a being to worship. Why is that the criterion of divinity?

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:39:00,610 ] You know, it's somehow as if we somewhat arrogantly have our idea of what God must be, and therefore God must live up to that, match that, or we're going to throw that idea of God — that God — in the bin. But it's interesting you both thought: well, a God that seems a little more realistic — to match our human experience.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:39:22,550 ] The God suffers when we suffer. The classical high theology says the perfect being can't suffer. The perfect being is completely self-sufficient — not even clear why there's a world and people, you know. Well, I kind of thought I'd rather have a God that can suffer.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:39:42,120 ] And in fact, it turns out the story is: God suffers when we suffer. And when we do bad things, God's suffering the way a good parent suffers if their kid's dealing in drugs or something. So anyway, I found that a fascinating thing — that you also feel that way, Scott.

Scott Langdon [ 00:40:17,340 ] We've talked about this a little bit before, but playing a character who makes terrible decisions hurts me. It hurts me. It really honestly does. Over the last five or six years — we talked a little bit earlier in this episode about taking a little bit more stock about how I particularly do what I do as an actor — and one of the things that I've really been digging into over the past several years is this personal relationship with my characters that I play.

Scott Langdon [ 00:40:54,890 ] In preparation to play them, I learn the lines that are in the script. And there's something to that. Also this idea of the script — that there's, you know, to veer outside of the script and imagine it — “Oh, the way I might want to write it” — well, this is the script to which, as an actor, you are a servant.

Scott Langdon [ 00:41:22,140 ] To the writing, to the story, to: here's what's going on. And so I can't say, “Well, if I were in this scenario, I wouldn't make this decision.” Well, of course not, because you're Scott. You wouldn't do that. And if I were to play every role — and the only roles I would play are the roles that I agree with the decisions they make, and if I were in that situation, I would make them — that's not interesting to me, number one.

Scott Langdon [ 00:41:57,880 ] But number two, that doesn't challenge me. It doesn't stretch my empathy for people who are not like me — you know, any of that. So I talk to my characters. I ask them, “Why are you this way?”

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:42:06,130 ] And that's fascinating, Scott, you talk to them.

Scott Langdon [ 00:42:09,750 ] I do. And I understand that, again, the answers come back informed by the text — by things that that character would know and not know. And I don't imagine that the character would know everything that I know. The character doesn't know that other characters are speaking about them in a certain way, let's say. But I — the source of this character — I know these things.

Scott Langdon [ 00:42:46,820 ] In a very same way, there are things that I think other people are thinking about me or talking about me, but God knows the bigger story, right? So we can imagine it that way. Like: well, God knows. But God isn't doing — well, God can only do so much with the whole story.

Scott Langdon [ 00:43:12,000 ] I think about that too, you know, as the actor. I think, “Well, I'm going to play my role as I can, but these other characters are being played by these other actors, and they're going to be doing — you know what I mean?” So there's so much more to it than I could ever understand.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:43:16,300 ] Well, I'm struck that the character — as you said early on in these discussions — you're not doing a kind of pretend, “let's make up an imaginary character.” You're creating a real character. And a real character has the character's own purposes, intentions, failings, situation.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:43:44,000 ] And I know novelists write about the character. The character, therefore, has to have a certain autonomy. It can't just be an aspect of Scott — or an aspect of even the playwright. It has to have autonomy as a character, with his or her own motivations, etc.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:44:02,130 ] And I know novelists sometimes say, as they're reflecting on the writing process: “Well, I'd intended it to end one way, but the character would not permit that.” That's because they're committed: a real person has a kind of integrity. I don't mean that as the virtue — I mean just a kind of coherence. The parts fit together a certain way. That makes them tick. And the story has to unfold compatible with the character they have made real — that they have created.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:44:40,580 ] And so I find it interesting. Because of that, you're actually able to sort of talk to a character. You know — if you ask the character this question, what would the character say? And just like the novelist: you're into the character, the character has autonomy, and so you know the character would say something, and you might even sometimes be a bit surprised when you actually go through it — that, oh, I thought it was going to be some more obvious or humdrum answer. And oh — yeah — huh, that's interesting.

Scott Langdon [ 00:45:12,470 ] This happened to me just last week in a rehearsal. Where I said something, another character said something, and I exit the stage. And as I was exiting the stage, it was like the character said to me, like, “Did you hear that?” And I said to myself, “You know — yes.” And I hadn't heard it before, which now made me understand something differently.

Scott Langdon [ 00:45:44,000 ] So the next time I went on as that character, I now know this. And so it changed the way I said a line. Do you know what I mean? So in that sense, I'm talking to the character. In that sense, I'm going world to world. I mean, the world that we're creating.

Scott Langdon [ 00:46:01,520 ] We have — as the players, as the creative team — and it's not just the actors, but it's also, you know, the lighting design and the sets and everything — we've come together to create this set of circumstances. And we've invited the audience to come in and suspend their disbelief, but to also participate in this world as if it were real. And so to take a step back from that and talk about reality and real life: if somebody comes at me in a certain way, I can step back and go, “This is the scene we're in now.”

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:46:41,390 ] Yes.

Scott Langdon [ 00:46:41,790 ] And so I kind of ask the director, quote-unquote — “God” — like, “What do you want me to do here?” “How can I be right?” Well, and then — so what's guiding you, you might ask. And so I would like to think — and this is the practice, isn't it — is in every situation like that, can I say, “God, I am open and non-exclusive in my desire to do your will in this scene. What is it?”

Scott Langdon [ 00:47:12,000 ] And then, if, you know — so somebody is angry at me — how can I balance that? How can I look past that and see they are suffering somehow? They are looking for something. What is it? How can I serve? So it becomes: how can I play the role of you in this situation, God? How can I be love in this situation?

Scott Langdon [ 00:47:33,950 ] You know how I like to take the word God and put love in it. I feel like that exercise has shaped me dramatically — replacing the word “God” with love — even if it's only in my own mind — to ask: what is love's will here? And then play that role. It's a practice, for sure.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:48:00,020 ] Yeah, yeah. And something I sometimes recommend to the agnostic — I don't know if Sam Harris would do this exercise; he would reject it — but if you're just an agnostic, you're searching, you're uncertain, I suggest: pray.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:48:17,480 ] And you don't have to — you know, my first prayer, I didn't believe in God. I just felt the first prayers were prayers of gratitude, basically. And I just felt gratitude to the universe, or whatever is up there — whatever is responsible. So you don't have to believe in God in order to pray. You can address the prayer to God.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:48:46,000 ] And then you've got to quiet yourself and not have all these other thoughts cluttering your attention. Just write down what comes to you. Abigail and I, over breakfast, were talking about Viktor Frankl who wrote Man’s Search for Meaning based in part on his concentration camp experiences. I guess it’s a concept he has as a practicing psychotherapist. He said the weakness of Freud, is Freud was only aware of the lowest level of your unconscious, the ID and so forth. But you have a spiritual unconsciousness. Just let your spiritual unconsciousness or without having that concept, just write down what comes to you and then just ponder it and see if maybe it has an element of divine — or if it's a bit like you and the character: you don't have, maybe, this God character giving you some insight into your life. So you can start there. Start anywhere — but that's one place to start.

Scott Langdon [ 00:49:53,330 ] Yeah, when I do that with a character, it's almost like — I don't want to say reverse praying, but in a sense it is. I mean, if I were me — Scott — praying to God, asking, “God, why is life like this? Why am I having these struggles? Or what do you want me to do? Or how can I be the fullest version of what I have to be in my story?” And as you say — maybe write that, write down what comes to me, be quiet, take in whatever answer it might be.

Scott Langdon [ 00:50:26,000 ] And we've talked about that could be many different ways. Maybe it could be something my wife says to me — which has happened. Maybe it could be an experience of somebody else that I see — treating someone else a way — or my best friend calling me out of the blue and saying something. Like, it could be anything. Or it could be from within — this idea — a set of words, whatever.

Scott Langdon [ 00:50:50,570 ] I think about that the other way. I think about it when I talk to my character — that I'll say, “Hello, character. Why are you doing these things?” And I listen for the character, and the character might say something back to me because they said this or this or that or the other. And it's this conversation.

Scott Langdon [ 00:51:18,000 ] I don't take it as seriously as I take prayer in that way. I'm not trying to compare the two in terms of — but just in terms of degree, let's say. But in terms of kind of thing, it's very similar. Because there's this open dialogue, and I'm trying to be as open with the possibilities of my character because I want them to be the fullest version of themselves they can be, which is what God wants of me. So there has to be this possibility of communication.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:51:53,080 ] Yeah — and it's nice that, with or without belief, we can communicate with God, as I've told in one part — amazingly. I always think of the universe, the cosmic whole — the parts can communicate with the whole. That's sort of an amazing fact.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:52:26,000 ] But here we are, and a lot of people say, “Oh, we can't know anything about God.” When I first had the God experience, I was struck by how much we do know about God. Across all these cultures, people are aware of God — in different vocabularies and so on. Different stories spin out, though often you can rather closely compare them to one another — but people have been aware of this divine dimension across the globe and across the millennia.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:52:49,029 ] I traced all these things back as far as I could go — to the Chinese oracle bones, which are almost preliterate. The first examples probably of Chinese characters appear on these oracle bones that were used for divination. You're trying to get divine guidance — often used by a ruler, a king or a tribal leader — whether to hunt today, whether to go to battle, you know, and so forth. I would pray.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:53:16,490 ] What they did was cast these oracle bones, and then little cracks would appear, which resembled Chinese characters, you might say. So they would get a message. So there are many ways.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:53:33,000 ] The main thing — I don't worry about, well, how is God behind the oracle bone cracks? I don't worry about that. We're the instrument. So it's a question: what comes to you? When you read tea leaves, or whatever it might be.

Dr. Jerry L. Martin [ 00:53:44,230 ] Abigail and I get Chinese food and we always read the fortune, and it usually isn't very relevant. But one time — the first time we ever had a meal together — she came to Washington. Near Union Station is the Chinatown, as they call it. We went to a Chinese restaurant and got our fortune cookies at the end of the meal. And here's mine, here's hers — they're identical. And that's the only time we have ever gotten identical fortunes. So, okay — I'll accept it. I'll accept it.

Scott Langdon [ 00:54:20,480 ] Thank you for listening to God: An Autobiography, The Podcast. Subscribe for free today wherever you listen to your podcasts and hear a new episode every week. You can hear the complete dramatic adaptation of God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher by Jerry L. Martin by beginning with Episode 1 of our podcast and listening through its conclusion with Episode 44. You can read the original true story in the book from which this podcast is adapted — God: An Autobiography, As Told to a Philosopher — available now at amazon.com, and always at godanautobiography.com. Pick up your own copy today. If you have any questions about this or any other episode, please email us at questions@godanautobiography.com, and experience the world from God’s perspective — as it was told to a philosopher. This is Scott Langdon. I’ll see you next time.